Our atmosphere is open and fluctuating, susceptible and conditioned by many human interferences; noise, industrial burning, exhaust fumes and our own exhalations. Weather emerges in momentary configurations of elements, energies, and forces, including the crowded, human-inflected air chemistry that effects catastrophic shifts in climate. I narrate a series of atmospheric encounters, weather reports of a kind, about three recent artworks that bear witness to our immediate and future weathers and the longer temporalities of climate heating. The first report is Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s collective ceremony To Burn, Forest, Fire (2021–2024); the second is Mithu Sen’s installation I Bleed River 2124 (2024) from New Delhi; and finally, theatre director Zuleikha Chaudhari’s fictional performance In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing (2023) that took place in Chandigarh.

I breathed in the aromas of Paterson’s incense burning ceremony in Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland, shared through the World Weather Network, a global network of artists, writers and communities responding to the climate crisis.1

Paterson’s ceremony, including incense sticks sent by mail, was performed over more than a year in many parts of the world, offering a collective moment of pause to inhale and remember the evolution of forest life through our lungs. I suggest that such sensorial actions fold into an understanding of the urgent action required of us all to mitigate the ecological crisis. In a recent visit to Delhi, I spoke to Mithu Sen and Zuleikha Chaudhari about their respective installation and performance works that foreground anthropogenic permutations of air. These two latter artworks were commissioned by Khōj International Artist Association in New Delhi, an organisation who are also part of the World Weather Network, and who have long explored questions around the role of art in atmospheric politics.

Weather appears as an artists’ live medium, yet weather always slips beyond our control, and now the runaway effects of climate crisis inflect every conversation about the weather. This article eddies around the weather conditions suffusing these artworks in a form of bodily climate witnessing.2 They each directly or indirectly advocate for the Rights of Nature, along with social justice, drawing rituals of breath, speculative aesthetics and ‘experimental jurisprudence’3 into their weather-worlding.

1 March 2023, 25 °, AQI 21, Cockle Bay, Aotearoa New Zealand

On a clear summer day, we lift back the orange-and-white-striped hazard tape surrounding the four-hundred-year-old pōhutukawa tree named Te Tuhi a Manawatere (the mark of Manawatere). I clutch Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s instruction booklet for the ceremonial artwork To Burn, Forest, Fire in my hand. James Tapsell-Kururangi has already set up the incense sticks that tightly hold the aroma of the first and last forests, along with a bell on a small wooden table. Commissioned by the Finnish art organisation, IHME Helsinki in 2021, a partner organisation in the World Weather Network, Paterson’s contemporary incense ritual To Burn, Forest, Fire4 is hosted in Aotearoa by Te Tuhi. Director of Te Tuhi, Hiraani Himona and I represent the World Weather Network programme, however the event is led by female Tangata Whenua, the Indigenous people of this place. Through mail, we (and a dozen or more small arts organisations in the World Weather Network) received Paterson’s incense sticks carefully packaged and with instructions. The IHME Helsinki commission emerged from Paterson’s practice of amplifying sensorial connection to our fast-diminishing natural heritage across vast time scales, from forests to glaciers, at this critical time of sixth mass extinction5 for plants and other species.

The sacred tree where we gather has been marked off with the orange/white tape by council tree workers as broken branches have just been removed. Within the last six weeks two severe cyclones—Cyclone Gabrielle and Cyclone Hale—have slashed a saturating and deadly path through the North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. People have died, animals have been washed away, houses have been destroyed, and many pōhutukawa trees have tumbled into the sea. These fallen giants once grew at perilous angles on cliffs in coastal regions, where their ropey spreading roots played a vital role in stabilising our shorelines. But edges of land once stable in the clement Holocene6 collapse in the carbon-soaked air and increasingly turbulent weather.

Today, the group is fanned by a light sea breeze. To begin To Burn, Forest, Fire, kuia (elder) Taini Drummond leads the assembled group towards the enduring tree. She performs a karakia, a ritual incantation. We sing a waiata, a song that Taini has composed for this ceremony, her words reaching back in time to the ancestor and astral traveller Manawatere who once marked this tree so future travellers by waka (canoe) would know the way to the shores of Aotearoa. Te Tuhi’s Pou Ārahi (principal cultural advisor), Carla Ruka plays pūtangitangi (flute) releasing gentle sounds that mingle with cicadas and the lapping sea. Taini leads us forward beneath the ancestor tree. The group of about twenty people, Te Tuhi’s elders, the perpetuals, quietly tread the carpet of leathery leaves and the low spreading branches. I slowly begin to read Paterson’s introductory text, and as instructed, I ring a small brass bell to commence the incense burning of the first and last forest.

James lights the First Forest, a bright green incense stick releasing scents from the oldest known forest in Cairo, New York State by the Hudson Valley, a forest that lived 385 million years ago. A thin curl of smoke mixes with the ozone from the ocean. The buried forest was discovered through fossilised root systems containing three types of ancient plant species, including Archaeopteris, which had well-developed roots, a large trunk and branches with leaves, akin to our pōhutukawa’s complex root systems. Paterson collaborated with the Japanese perfumers and incense makers Shoyeido, and with geologists to characterise these forests with aromas. The incense diffuses molecules of a very specific type including basic, identifiable elements from the ancient Devonian era environment before plants evolved to bloom with sugary flowers or fruits; the ancient forest soil was damp, the plants were something like what we know as mosses and ferns. There would have been no carpet of leaf-litter as there is today under our pōhutukawa, with its fingery red flowers, as deciduous species had not yet evolved.

One by one our assembled group inhales the incense scent of this transported ancient world. Carla Ruka has also set out a bowl of karamea, red ochre from a neighbouring soil, and each person dips their fingers in the pigment, then touches their hands to the ancient rough grey bark of the tree. Time becomes circular as we reenact the primordial mark of Manawatere. The touching is an attuning to the tree, to the many weathers the tree contains.

Katie Paterson, To Burn, Forest, Fire (2021–2024). An ancient pōhutukawa tree

named Te Tuhi a Manawatere is marked with karamea (red ochre) during the

incense ceremony hosted by Te Tuhi on 1st March 2023, Cockle Bay, Aotearoa

New Zealand. IHME Helsinki Commission 2021, shared on the

World Weather Network. Images courtesy of Te Tuhi.

I ring the bell again. When James lights the second, dark green Last Forest incense stick we are carried back to the present, to the scent of a living forest biome under threat from fire and human consumption: the Amazon Rainforest. For this aroma, Paterson’s collaborator, Dr. Ana María Yáñez Serrano introduced her research on airborne volatile organic compounds (VOCs) to describe the chemical constituents of the modern rainforest scents. The isoprene emitted by our pōhutukawa tree in Aotearoa melds with the molecules common to the trees and abundant plants in the Amazon. Yet the dozens of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes unique to the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve in Ecuador, permeate the atmospheric chemistry of the gathering here in Cockle Bay. The tingling scent of the Tiputini station in Ecuador is described by Paterson and her collaborators as follows: “a stunning array of scents, from the alcoholic fizz of guava trees to the fresh peanut-like aroma of the Earth, all combining in a unique sweet and bitter fragrance of the modern Amazon.”7 Like the Amazon, in the past two years we have been subject to flood and fire. The reverent quiet that falls over the group suggests a deep biome vibration with the uncertain fate of this forest far from us.

According to geologist David George Haskell: “When volatile molecules, those chemicals that we call ‘aromas’, enter our nasal cavities, they bind to fragile microscopic hairs on receptor cells. These cells then signal to the deepest parts of our brain, neural centres where memory, emotion, and a sense of time reside. Aroma moves us, working below and at the edges of conscious awareness.”8 The scent in the air carries us back and forth across time and space, just as the roots of the pōhutukawa conjoin recall the primordial roots of the Devonian forest. We float back to the time of the mark of Manawatere, the ancient, astral voyager who travelled on a waka made of feathers; and back further, ten million years, to the time when pōhutukawa trees evolved and spread throughout Te Moana nui a Kiwa, the Pacific, carried on ocean currents.

Our ceremony at Cockle Bay fused our breath with ancient and present forest airs, collapsing distance, decelerating us, recalling species and plants that have disappeared or exist precariously as wildfires threaten the Amazon. Paterson’s ceremony invites the deep inhalation of the carefully constructed particulate she releases, rather than the thoughtless volatile compounds spat out by cars or the factories chasing multi-national capital. The act of inhaling approaches what Astrida Neimanis and Blanche Verlie (2023) call: “a mode of more-than-human witnessing” of climate catastrophe. They argue: “…to breathe climate catastrophe is to witness one’s own body-in-and-as-part-of-the-climate. Put otherwise: we are the climate change we witness.”9 We become the ancient trees and tempests to come, they dwell within our bodies. This attuning might invite us to suppress our toxic emissions in our everyday lives.

2 February 2024, 14°, AQI 425, New Delhi, India.

The air is gritty with metallic soot; through grey-yellow fog, a limpid sun. A weather App sends me a ‘SEVERE’ air quality warning. It‘s raining in intermittent bursts on the opening evening of the group show 28° North and Parallel Weathers. The curators have set the provocation: “What World opens up to us when we think of the body as a site for attuned sensing?”10 Wetness pervades the three tiers of gallery spaces around the open plan courtyard of Khōj International Artist Association in New Delhi, where my collaborator Rachel Shearer is performing a live electronic audio composition on the rooftop.11 The dirt road came awash with a fast micro-flood of the urban village of Khirkee and the damp swept up my long skirt, tugging at my skin; the rainwater an ever-present mediator of this encounter.12 We are in New Delhi through our work with Te Tuhi, a sister independent contemporary arts organisation to Khōj and IHME Helsinki, again conjoined in the activities of the World Weather Network. After two years of remote conversations between artists, scientists and writers among 28 small arts organisations, the WWN platform was launched online in 2022. We met in the making of creative weather reports with artists, writers, performers and scientists. Our parallel programmes metabolise and forecast matters of art, environmental justice and social inclusivity.

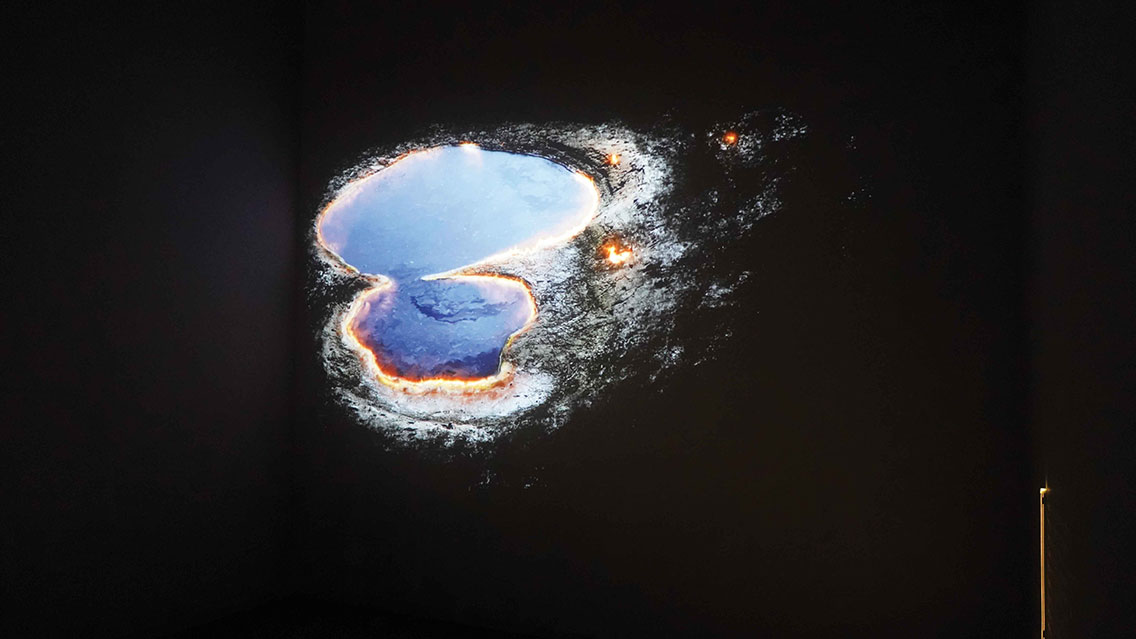

Mithu Sen, I Bleed River 2124. 28° North and Parallel Weathers, Khōj (2024).

Courtesy of Khōj International Artists’ Association.

I shelter at the edge of the courtyard with artist Mithu Sen, also exhibiting in Khōj. Sen is an inhabitant of New Delhi, born in West Bengal. As the rain falls heavily, we huddle in the reading room and talk about her installation I Bleed River 2124, where she traces the confluence of war and climate change. A projection of a burning river in toxic air dominates the room, while a smaller iPad narrates her journey along the present trans-boundary river, the Brahmaputra. The river, of rapidly diminishing width, and heavily compromised water quality flows through Tibet, Northeastern India, and Bangladesh, and has different names including the Luit in Assamese, Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibetan, and the Jamuna River in Bengali. For their World Weather Network project, Khōj invited artists to take a journey along the 28th Parallel North Latitude—which passes through Mount Everest in Nepal, the Northern Himalayas with Rajasthan in India and the Sindh Desert in Pakistan. This imagined cartographic line is an entry point for Sen and other artists in this exhibition at Khōj to speculate on future weathers of the ongoing climate crisis and the violent nature of the increasingly militarised human borders across the continent. A neon tube leads us from the gallery’s interior to the external courtyard and the date 2124, one hundred years from our wet present. Sen’s accompanying text reads:

Once upon a date, there existed a river named River sacrificially immersed in a distant inferno sparked by bombings, fundamentally altering the narrative of what was once known as a river. The flames from a faraway bombing ignited the river and became a transformative force, shaping a new storyline for this ethereal being in a tangible setting.13

In the Weather Glossary of artists’ terms that accompanies the exhibition, Sen has recorded the latitude of locations of 21st century wars: Baghdad; Gaza strip; Khartoum; Mariupol; Myanmar, West Bank and timestamps in the artwork draw parallels between the point at which they have been recorded in India. Sen’s speculative installation forecasts deadly flames from missiles dropping like rain from the air, recalling philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s ‘dark meteorology’ that attempts to destroy the combatant’s environment through poisonous gas.14 Anthropogenic wars collide with indifference to the changing climate.

Weather Glossary, Reading Room at Khōj. 28° North and Parallel Weathers, Khōj (2024).

Courtesy of Khōj International Artists’ Association.

The morning after the deluge, we visit the India Art Fair in Okhla, New Delhi. Passes scanned and bags x-rayed, we arrive to the vibrant commerce of the Art Fair halls on the once densely populated flood plain of the Yamuna River. Residential colonies in the narrow dirt lanes of have been rezoned as the NSIC Exhibition Grounds15. Outside swarms of dust, insects, circling kites (avian predators), jacket-wearing dogs and people subsist in barely breathable air. This is February in Winter: the air will become even more thickly laden with particulate matter from the agricultural fires of late Autumn. Cloggy molecules from exhaust fumes and factories cling to the remaining oxygen in the air, exacerbated by the naturally occurring fogs of low-lying Delhi.

In a knot of people after an intensive panel on the political agency of art, I meet theatre director Zuleikha Chaudhari and we stand out of the fray for a short, intensive conversation.16 She is the artistic director of the performance In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing, a fictionalised court case conceived with Khōj International Artists’ Association in collaboration with lawyer Harish Mehla.17 The hearing on the corruption of the air is staged at the Open Hand Monument at Chandigarh in the golden light of evening refracted through smog. Chandigarh serves as the shared capital of Punjab to the north, west and the south, and Haryana to the east, regions where farmers were forced into unsustainable practices of stubble-burning by the conversion of the water-intensive wheat and rice-growing areas in the 1950s. Water can only be used for three months of the year so this intensifies multi-cropping on arable land from paddies to wheat fields. Multi-cropping demands fast turnover of crops and clearing by fire of the stubble-remnants each season. The unbearable air that this burning practice causes is brought to the performed court for a hearing filed by Khōj International Artists’ Association, Zuleikha Chaudhari and Maya Anandan, represented by her mother and legal guardian, Ms. Radhika Chopra.

In multiple languages, Hindi, Punjabi and English, the staged performance revolves around the Rights of Nature as an extension of the Right to Life within Article 21 of the Constitution of India. The hearing is enacted by actor-lawyers, real artist-activists involved in relational art practices with farmers, and a fictitious Farmers Union, whose livelihood has become dependent on stubble-burning. While taking place in the thickness of open air, the hearing still adhered to the legal protocols and procedures of the National Green Tribunal in order to explore principles of natural justice. The script developed with Harish Mehla took several years to write and drew on previous trials and collected testimony. Collectively the complainants indict the Union of India through the Ministry of Environment. The human-mattering of air, the matter of justice for the biosphere, and the social toll on humanity suffuses the arguments put forth by these three parties. The atmosphere of Delhi and Chandigarh appears as a modernist haze, which according to Steven Connor, “brings the sky down to earth, or dissolves the grounds of the earth, dissolving the relations between sky and earth, creating interference patterns between high and low, frontality and immersion. The meaning of modernist haze is the loss of the sky – or, at least, the loss of its distance, its aura of unapproachability.”18 In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing enacts these real losses.

This hearing is “theatre but not theatre,” reflects the director of Khōj, Pooja Sood.19 Several of the actors making submissions to this quasi-fictional court hearing are environmental campaigners who have filed many real petitions to the government to uphold the Environmental Protection Act of 1986. ‘Real’ actors including three practising lawyers, Manmohan Lal Sarin, Mannat Anand, and Harish Mehla, appear before the court in the hearing. In addition, there were three subject-expert witnesses, Kahan Singh Pannu, Manish Shrivastava and Tarini Mehta, who is an Associate Professor of Environmental Law. Three ‘real’ retired judges complete with stiff white collars and dark gowns play themselves: Justice Rajive Bhalla, Justice Kamaljit Singh Garewal, and Justice K Kannan.

The artists, also playing themselves in the hearing, foreground their artwork as ecological testimony and social practice to bridge the urban and rural divide. They are artist and performer Shweta Bhattad, filmmaker Randeep Maddoke, and the duo Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra. Thukral and Tagra‘s (T&T) creative practice spans data visualisation, gaming, archiving, and publishing. While their early work dealt with the politics of consumer culture, their recent interest in ecology and climate change involved revisiting their own family histories of migration and farming in the state of Punjab. While in New Delhi I visited Sustaina (2024) at Bikaner house, an exhibition curated by T&T and Srinivas Aditya Mopidevi which foregrounded artworks, ‚grass roots‘ designed artefacts and materials that offer ways through the ecological crisis. A constitutive building material used throughout the exhibition for display was formed from wheat stubble, posing an alternative second life to ash and atmospheric particulate.

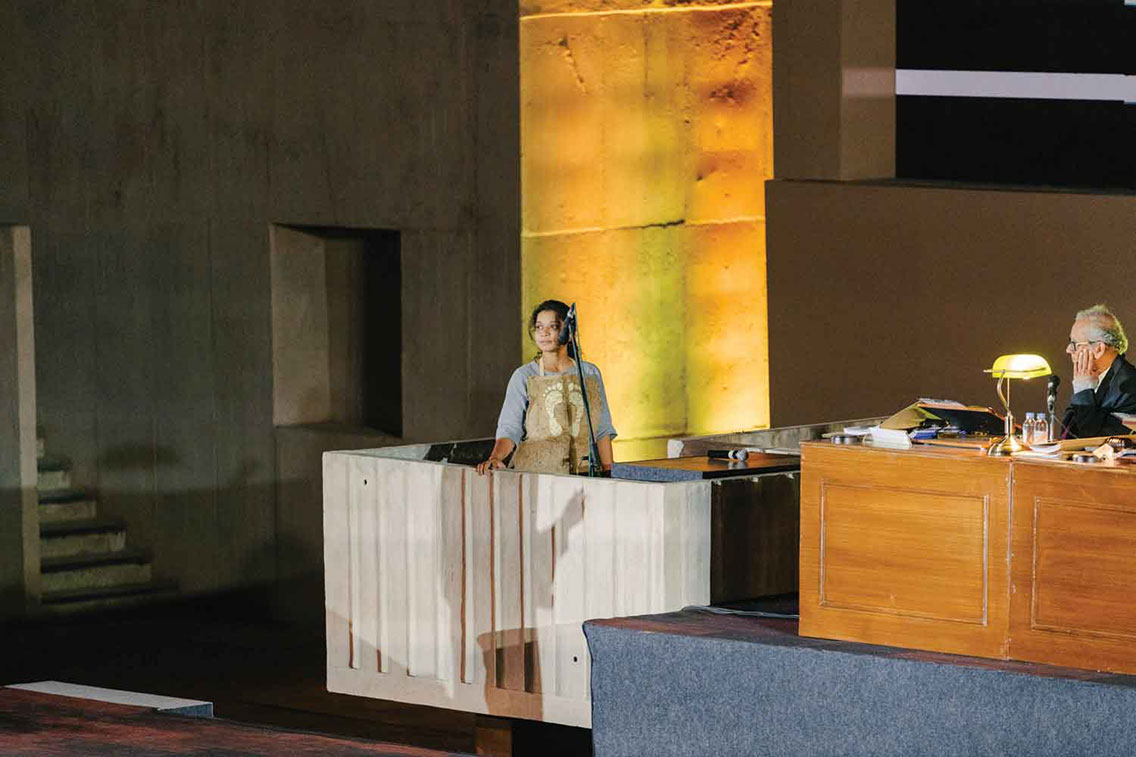

Khōj International Artists’ Association with Zuleikha Chaudhari,

In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing. Chandigarh (March 5, 2023).

Courtesy of Khōj International Artists’ Association.

During In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing in Chandigarh, T&T presented a board game as part of their testimony that traces the traumatic experience of women farmers whose husbands have been driven by suicide due to untenable farming conditions. They worked closely with women of the Punjab to understand the economy of loss through the failure of family crops as the climate changes, and also to understand how they survive. As part of T&T’s testimony, one round of their game entitled Weeping Farm was played by drawing cards and moving around the board, enacted in the court itself. When a card is drawn indicating cyclonic rain for instance, a player loses ground and moves back several places, embodying a rural character’s daily life through the seasons. Through empirical research the artists discovered the tragic statistic that every 40–45 minutes there is one farmer’s death by suicide, and this timeframe determines the length of the game. Weather circumstances and cycles of cropping are critical to the lives of the surviving widow-farmers but they are trapped in an end game; they cannot separate their livelihood from the changing climate.

Artist Shweta Bhattad, dressed in a raw cotton worker’s apron printed with a footprint, presented a video of the turning pages of a handmade book as evidence: The Eaten Cotton…A Love Story…A Cook Book (2022). The soft raw cotton, screen-printed book is an illustrated encounter between cotton-growing, weather and culture, a material witness to ecological upheaval.20 Bhattad is a founding member of the Gram Art Project Collective, a group of farmers, artists, women and makers who all live and work in and around the village of Paradsinga. The story, told in letters, follows two characters through the origins of cotton cropping to the realisation of the demand to relinquish the boundaries between human and non-human, old and young, city and village in order to survive: a collective concept developed through the Gram Art Project, signalling a return to Indigenous knowledges.

Khōj International Artists’ Association with Zuleikha Chaudhari,

In the Matter of the Rights of Nature–A Staged Hearing. Chandigarh (March 5, 2023).

Courtesy of Khōj International Artists’ Association.

The final artist-witness Randeep Maddoke’s film, Landless, documents the caste dynamics and bleak conditions for Dalits, agricultural workers in the Punjab region, including itinerant goat-herders in an unfolding ecological crisis. The three artworks each have in common a socio-relational human struggle with the new weathers, providing experiential testimony of an uncertain future. This project continues Khōj’s concerns with creative forms of testimony in many projects since Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness (2017).

The testimony of artists in the hearing, alongside the environmental lawyers and the farmers responsible for the burning, demonstrates how art in the form of “experimental jurisprudence” ignites the public sphere and calls for real change to be effected. Artists invent forms of experimental jurisprudence when legal and State mechanisms fail, to cite a phrase T.J. Demos developed in relation to artist Amy Balkin’s atmospheric propositions to the U.N.21 This might also be extended to the non-human: an owl alights on the Open Hand monument at the beginning of the video document of the hearing—an assembly across species divides. The owl might say, it is not only human bodies that are suffocating silently, look at us in the skies. At the end of the trial the judges affirm the claimants call for the rights of nature, and call on the whole nation, represented by the government to respond, rather than any one community. A “compromise settlement” is reached. Zuleikha tells me urgently that the next step is to take this fictional hearing concerning the rights of air to the real National Green Tribunal. Later that night, our group walk passed the arched green-lit, yet faded gate of the National Green Tribunal, a legislative body effectively suppressed under the government of Narendra Modi.

Experimental Jurisprudence and the Rights of Nature

Both Aotearoa New Zealand and India have pioneered radical environmental jurisprudence; considering the legal personhood of rivers and forests. The laws in both the immense continent of India and my tiny island are rich in protections of ‘Naturehood’, however, their implementation is poor. In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing reflects an ecocentric turn in the last decade in juridical thinking in India, even if the implementation of environmental protection has been poor. Economist Rita Brara (2017) argues that India has “made some steps toward navigating an ecocentric course, even if intermittently, by experimenting with a language for the Rights of Nature that draws on India’s Constitution, the drift of international currents and treaties, the judgments of its apex and provincial courts, as well as the rulings of a green tribunal.”22 Brara suggests further that many of the religious and ethical traditions of the Indian peoples that venerate nature appear in their juridical thought. She notes: “The notion of dharma, translated as ‘conduct’ according to inherent qualities or character, is understood to characterise all of Nature. […] Nonviolence or ahimsa, too, continues to be an influential strain of thought in Indian religious traditions and affects the judicature as well.”23 In indigenous Māori worlding from Aotearoa New Zealand, weather elements are also ancestors and empathise with or affect human circumstances; the weather atua, supranatural beings, may be called or herald the oncoming weather. Artists trace the temporalities of weather in our bodies and in machinic data sets as well as legal systems.

In a judgment by the High Court in the province of Utttarakhand, Northern India, the ground-breaking law to recognise the legal rights of personhood to the Whanganui River in Aotearoa New Zealand was cited (2017). The court declared that since the Ganges and the Yamuna are sacred to a large number of Indians, these rivers should be accorded the status of living entities and granted the rights of a juristic or legal person in March 2017. However, the judgment of the provincial court at Uttarakhand was overruled by the Supreme Court of India in July 2017 on the grounds that it interfered with the rights of other provinces and raised issues concerning who would be regarded as responsible for compensation if the rivers were to flood.24 In relation to flooding of the Whanganui river, these objections have yet to manifest.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the current right-wing government under Prime minister Christopher Luxton has repealed incentives for clean-cars, removed petrol taxes and smoke-free goals in his first 100 days in office—ecocidal acts of revenge politics following an era of centre left-government. The planet-upheaving cyclonic weathers that continue from these brutalist policies force bodies, biota and technologies into new assemblies.

Aerial Revolution

The art projects encountered in this narrative foment an aerial revolution that comes from the ground, from the breathers of air. They rally us to face the changing climate via the senses, to see the body itself as a sensor, and to reconstitute the impossible air of the present. Although weather is inconstant, it is crowded with substances, memories, and histories. As Connor has argued, the atmospheric science of urban meteorology has shown that since the 19th century the atmosphere “…is not just affected by contamination and irregularity—it is constituted by it.”25 When the exhausted air is filled with exhaust fumes and fog becomes smog, our bodies become smoggy through the act of respiration. The effects of the changing climate, visible and tasteable in the air, are symptoms of violent systems of power including the capitalist-colonial legacy in India, Aotearoa New Zealand and everywhere else. To recognise the rights of air is to guarantee our future survival along with our co-species.

When I left New Delhi I unspooled a trail of fossil-fuelled molecules from the petrochemistry of ancient forests. I left behind people living air-conditioned lives, and many others with no choice but to live at the roadside, always living in the air, in the exhaust of those who can move on. Yet in the thick air of my memory is also the scent of spices, the deep call of oud, and the light particles in ancient mosques swirling through porous panels. Within the clean-dirty spaces of aeroplanes, climate-controlled shopping malls and art fair exhibition halls we exist in modified weathers, buried in the staleness of regurgitated machinic air. Of fossil-fuelled travel, Connor writes: “For a mobile people, waste is the past.”26 Although this flight to India was my first long haul plane trip in six years, and a journey for which I weighed up the benefits of my presence as an artist and researcher, my carbon trail in the upper atmosphere, absorbed into the ocean, is the incontrovertible, biophysical thing: along with the Delhi air carried to the other side of the world inside my lungs.

The willing inhalation of incense in Paterson’s To Burn, Forest, Fire is an active co-respiration with trees and other species, or conspiration, an embodied form of witnessing to follow Neimanis and Verlie. The ceremony accentuates the simple biological connection we have to the respiration of trees through our breath. On the other hand, we are powerless to control our inhalation of unwanted atmospheric toxins without changing our fundamental desire for mobility and consumption. Neimanis and Verlie state:

We breathe together to survive, to empathise where possible, to recognise incommensurate suffering, to connect and entangle with others through shared breathing, and to create knowledges and responsibilities for breathing new worlds into life. Conspiratorial witnessing is therefore a breathy practice of collective action for climate justice.27

Air is now laden with compounds, it is a matter of concern never intangible or separate from culture; our atmosphere is becoming untenable for life, we breathe our waste. Artists witness, testify and speculate in powerful biophysical connections to weather as medium. Such artworks reflect the labour of extraordinary and radical thinking through experimental forms of environmental justice as in In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing; rituals in the case of Katie Paterson’s To Burn, Forest, Fire; and real politics fused with future speculation in Mithu Sen’s I Bleed River 2124.

6 February 2024, 21°, AQI 370, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, New Zealand

No sooner had I arrived home when my phone pinged in an emergency alert: my suburb was on fire; close all the doors and windows to keep safe from toxic smoke. Out of sight on the industrial edge of town a refuse station was burning, the winds carrying the unwelcome airborne matter of burning plastic to my home. While last Summer the cyclone-drenching floods swept my city and pōhutukawa trees and homes slipped into the sea, this Summer of 2024 a drought and hot El Niño winds have caused a fire to escalate. For three days the sound of helicopters fills the air, heaving monsoon buckets of sea water from the harbour to dowse the flames.