James Geurts—Weatherman

James Geurts performs many rituals, through which he tells many stories, involving water and journeying, incorporating them in temporary arrangements of light and 3D structures. These are accompanied by less ephemeral marks on man-made surfaces, notably drawings and photographic prints. Fluidity, or mutability, is his leitmotif.

—Dr Julie Louise Bacon, Edinburgh,

Beyond interpretation and judgement, writing the story of art.1

I’m sitting on a North Melbourne decking with artist James Geurts, discussing the many weather-related projects he’s undertaken over the past three decades. We’re in 37-degree heat, as Australia feels the full force of climate change. Bush fires burn out of control west of nearby Ballarat. He’s telling me about Standing Wave: Drawing Tide, a work he made at The Bay of Fundy in 2012, and exhibited at the Dalhousie Art Gallery in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

“A standing wave is a phenomenon produced when the particular frequency holds an equal harmonic resonance,” he explains to me. “The Bay of Fundy is one of the only large tidal water bodies where the in-and-out-going tides harmonise with the shape of the geology, causing a natural “standing wave” phenomenon. This in turn creates extreme tidal pulses.” I’d heard talk of this mythical phenomenon when, as a young art student in 1973, I’d worked as a lighthouse keeper on three uninhabited islands off the West Coast of Scotland, experiencing all kinds of freakish weather, with fog being the most cunning.

Now I was hearing about it first-hand. “The in-situ research undertook 11 hours occupying the tidal zone (the duration of an in- and out-going tide) drawing and measuring the experience of how the body and perception comprehend such large bodies of moving water. The spaces between the fluorescent tubes with which the work was partly fabricated are intuitive, based on the site experience, in order to create a wave within a wave, a pulse that undulates both ways simultaneously to emulate the resonant frequency.” Later, I google this work, as I do the many projects Geurts has undertaken in Hoorn (Netherlands, 2014); London (UK); Israel, Palestine and the Occupied Territories (Middle East, 2011); Tasmania, (Australia, 2018)); Brussels (Belgium, 2010); Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts (Taiwan, 2017); Quebec (Canada, 2009); and Point Nepean (Australia, 2022). My online search takes me back to the Standing Wave: Drawing Tide project at The Bay of Fundy. In Visual Art News magazine (January, 2013), Allison Saunders quotes him as saying, “I see everything I do as part of a drawing methodology…sometimes I spend hours or days drawing, as a way of listening. Sometimes that’s the work in itself, and that’s enough.”

Geurts is a self-confessed psychogeographer. More than most he understands the Situationists’ old dictum, “The Map is Not the Territory”. He moves from East Jerusalem to Gaza or from Belgium to The Netherlands with the confidence and freedom of a river, more concerned with the physicality of the natural environment that frames him, than with cartography or currency exchange.

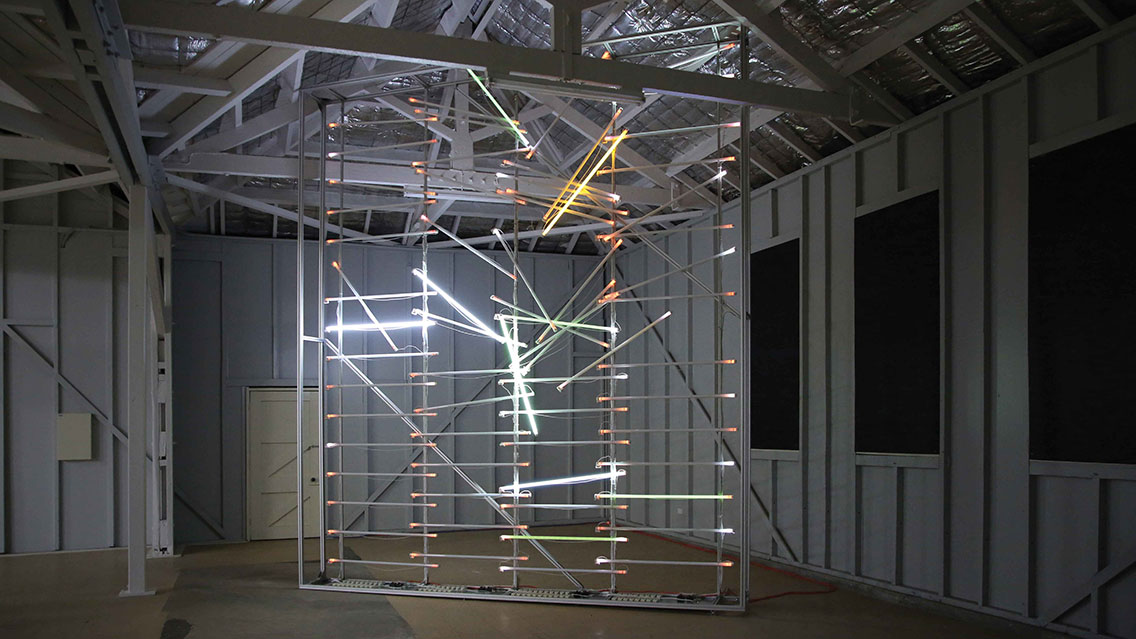

Floodplains Taipei, Melbourne

Floodplains, and how they are affected by local weather conditions, have also been of ongoing fascination to Geurts. Indeed Floodplain (2018) is the descriptive name for a major project based at the NGV Federation Square in Melbourne and spreading its liquid tentacles across the whole 242-kilometres of the Yarra River. In her catalogue essay (Perimeter Editions), Annika Kristensen speaks of Geurts’ “meticulous research process” that saw him “spend months traipsing the banks of the river itself, and trawling for information in the State Library of Victoria and in the Melbourne Water archives.” By contrast to this well-planned and meticulous research, the last major installation I saw of his was the huge contribution he made to the FrontBeach, BackBeach project in 2023, on the Mornington Peninsula. I was fortunate to witness him installing this Standing Wave from lengths of neon tubing and a rats’ nest of wires and cables. I saw him advancing through doubt rather than certainty as he tried different configurations and experimented with site-lines, taking decisions ‘on the hop’ as he tested some propositions and discarded others. The 4m x 5m high pulsing sculpture found its form as a grid of fluorescent tubes that appear to be collapsing under the pressure of extreme weather, unhinged tubes of light form a breaking wave, cascading down the centre of the sculpture.

I’d heard of another floodplain work Geurts made a few years earlier while on a residency at the Kuandu Museum of Fine Art, Taiwan. It was titled Watergate (2017). As the burning sun set over North Melbourne, I asked him to fill in the details. “Taipei City was built in a floodplain,” he tells me. “After realising this, town planners and engineers created many interventions of the river to prevent future floods, including a 10m high wall of concrete between the city and the Tamsui River, to attempt to prevent the city flooding during typhoons. Through the residency I investigated the vulnerable positioning of the city, exploring the management of the river, its straightening and infrastructure designed to avert flooding. I focused on a large, militarised dike wall, which is a potent marker of the physical and psychological barrier between the city and the river. The research centred on the Dunhuang Evacuation Gate, one of the few openings in the wall where large metal gates are closed if threatened by a typhoon surge. An initial durational drawing at the site reimagined the rupture of this threshold during a flooding event, where the gate failed to close. A bioluminescent light sculpture was staged at the same site, an outline drawing of a floodgate, underlining the critical juncture where nature and culture meet. The sculpture is an impossible proposition, a dysfunctional gate, amplifying the futility of trying to stop extreme weather. The light sculpture was positioned between the existing Dunhuang Evacuation Gate and the river, aligned to set up a new threshold, illuminated in the space between day and night. The sculpture was then reconfigured back into the museum, inverting the exterior experience to the interior space of the gallery.”

Messing with the Technology Interface

I ask Geurts about his use of colour, often but not always, through neon, and about other artists with whom he feels an affinity. He points me in the direction of an online review of his Quebec work in Reflections of Québec (2009) written by Anne-Lise Griffon and published in Inter Actuel magazine, No 103. She writes: “At the intersection of Land Art and Minimalism, this installation is paradigmatic of the work produced by James Geurts; time and the ambiance of luminosity intervene, playing a pivotal role in the construction of the artwork. Geurts transforms his chosen site into a moving body, permeable to variations in time and climate.” And in a footnote adds, “The installation displayed some of the characteristics of Andy Goldsworthy’s work with water and ice. The use of modulating light sources, revealing aspects of space, strongly evokes the work of Dan Flavin. For example, The Diagonal of Personal Ecstasy (The Diagonal of May 25, 1963), a work consisting of a single yellow neon attached to the wall of his studio at a 45- degree angle, prompting a re-reading of the space.”

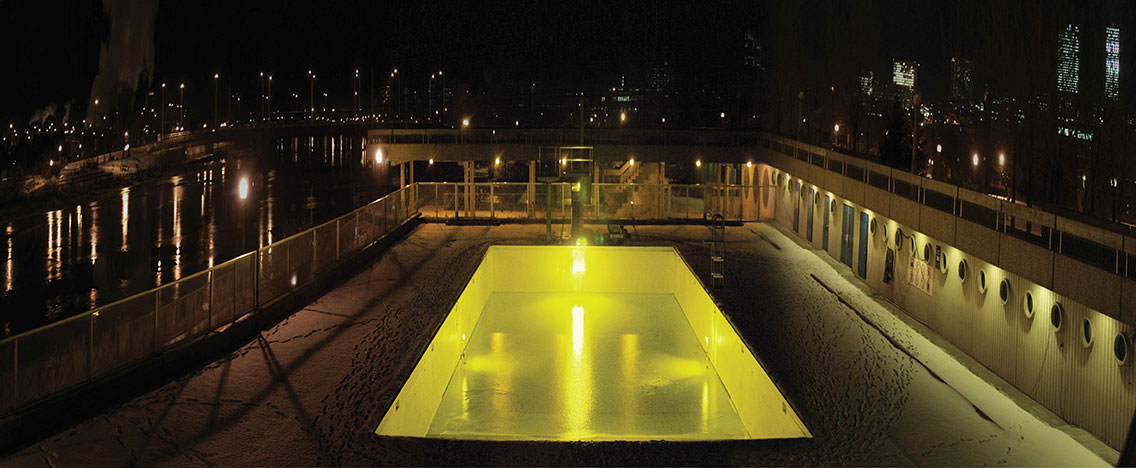

Geurts picks up the story in his own words, in a poetic monologue that he throws at me like a latter-day King Lear wrestling with the elements. “So I got permission to turn this local swimming pool, this outdoor swimming pool, into a living monochrome, into a living artwork to collaborate with the weather. I positioned yellow lights situated in each corner, and it created the whole pool mass, as a yellow monochrome… it kind of created a hearth, or a warm arena, to allow the weather to change visibly within the monochrome throughout the three months that the installation occupied. People could see from a walking platform around the top of the pool looking into it, through the winter, through snow… documenting how the work had changed through always changing weather conditions… It filled up with heavy rain, then it would freeze, and then there would be sleet, then deep snow… And then there was a big storm where one of the yellow lights, which was precariously positioned on the ice, got pushed over because it was heavy, fell into the ice, and it must have burnt its way through the snow, and when it hit the water, it created this electrical charge and created this amoebic electrical rupture-drawing through the snow. And it turned off…but also left the residue of it melting into the snow.”

‘Tip of the iceberg’ is a journalistic cliché which I would normally, to use another one, avoid like the plague. However, it is a phrase that relates to both the weather and climate change, and to the works of James Geurts. I have only exposed the very tip of his decades-long practice and would urge you to visit his extensive website to fully appreciate the oeuvre of this nomadic psychogeographer.

Standing Wave

Site-responsive kinetic light sculpture

5m x 4.2m x 2m

Point Nepean National Park, Victoria

FrontBeach, BackBeach, Public Art Commission 2022

Courtesy the artist

Flow Equation

4 x (2m x 1.4m x 17cm)

Neon, scanned work on paper, timber frame and Dibond

TarraWarra Biennial

TarraWarra Museum of Art 2021

Courtesy the artist

Living Monochrome

Site-specific durational light installation

20 x 8 x 3m

Piscine Saint-Roch, outdoor pool

La Chambre Blanche, Quebec 2009

Courtesy the artist

EON Project

Weather tracing frequencies

160 x 110 x 60cm

Bronze, white patina

T.C.L. Landscape Architects Australia, GAGPROJECTS Satellite exhibition 2022

Courtesy the artist

Watergate

Site and time-specific installation at Tamsui River

4 x 2 x 1m

Fluorescent lights, generator, timber structure

Dunhuang Evacuation Gate

Kuandu Museum of Fine Art (KdMoFA), Taiwan 2017

Courtesy the artist

Aqueduct Sluice

Light installation at site of Birrarung (Yarra River) intervention

Neon, solar, battery, converters

Floodplain Project, National Gallery of Victoria 2018

Courtesy the artist

Weather Action_P1 -20

Site-specific atmosphere photograph

150 x 160cm

Polaroid film, weather, dust

Framed print

Seismic Field, GAGPROJECTS 2018

Courtesy the artist

Roots, and a Very Long Leash

Peter Hill in Conversation with artist Franziska Furter

The weather is fundamentally necessary for life on earth but it can also destroy whole livelihoods in seconds. The weather always exists. It’s there day and night and never stops. It’s always in motion and it changes all the time.

—Franziska Furter, artist proposal for NGV Triennial,

3 August 2022

Peter Hill

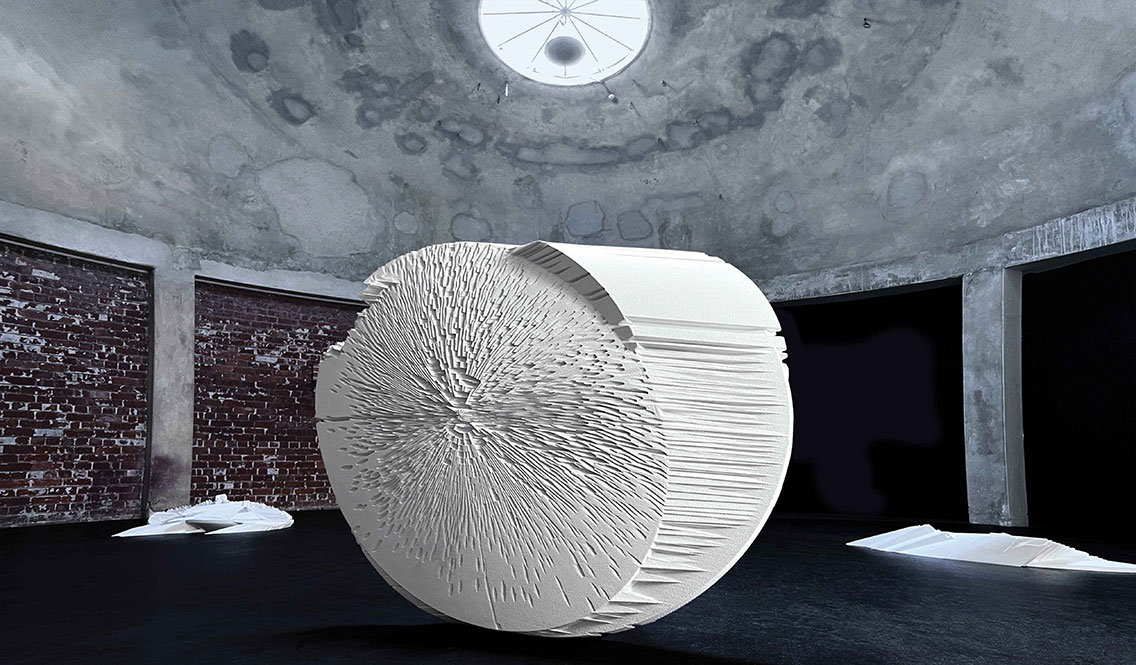

Your ambitious installation in Melbourne at the NGV Triennial was really in three parts that came together to make a whole. There was the huge, square, tufted rug, comprised of infrared satellite imagery of weather patterns, particularly hurricanes and super-hurricanes. Above it, thousands of glass beads hung like banks of fog. And on the walls of the large gallery hung 19th-century seascape paintings by a range of artists including Turner, drawn from the collection – many of which had not been exhibited in the museum for decades. Did you conceive it like this from the beginning, or did it evolve gradually, up to and including the install? Please talk a little about how you conceived this great work.

Franziska Furter

Since I got the first email from the NGV two years ago the Installation developed and evolved up to the last minute of installing. Many things have changed along the way as it often does. Sometimes I changed things and sometimes changes came from the NGV.

Often my first draft contains many components. I have to find out in which direction I want to go, and I start to reduce and sharpen. While working on the installation I have to learn to trust the work. With this installation it wasn’t easy as I couldn’t just go to the space and spend time there when I had a question as I was on the other side of the planet. I didn’t know the space and its atmosphere in person, so I had to rely on models and ground plans a lot, and also on the curatorial team.

Because models and ground plans only help to a certain point, I often like to keep some decisions open to be able to adapt the work to the space. This is sometimes difficult for the curators and even harder for the installation team because it means things can change last minute. I love it because often it is part of the work and in the end the installation is much better. I had to learn to trust myself with my last moment decisions.

Except for the Falls of Schaffhausen (c. 1845) by JMW Turner, which was already hanging in that gallery and I wanted to keep it, the 19th-century paintings were chosen by the curatorial team who know the collection really intimately. I am super happy about their choices. This Turner painting was on the first list I got from the NGV about the collection in my space and I loved the idea that the painting shows a place in Switzerland. And it travelled all the way to Melbourne, like me. It was the inspiration for Haku, the bead installation.

Peter Hill

Is ‘Weather’ a theme you have worked with before, and if so, how did it manifest itself? Can you describe some earlier projects?

Franziska Furter

The interest in ‘weather’ started in Edinburgh, Scotland where I spent six months as an artist-in-residence in 2000. It was amazingly present all the time and people loved to talk about it constantly as well. And because I was always interested in the invisible, the ephemeral, change and movement of the weather got my attention and seemed to be a great inspiration for my work and a wonderful source for my titles. Most of my works touch on the weather somehow, either directly or peripherally, but it’s always there somewhere. It does shape my work and me, as it shapes our surroundings constantly. Maybe this installation at the NGV is the most direct one so far as I use infrared images of hurricanes for the rug, and in Haku, the beads trigger the association of rain or fog quite directly.

Also in Scotland, coming from a land-locked country like Switzerland, I became addicted to the four-times-daily, mantra-like Shipping Forecast on the BBC, covering the coastal waters of Britain.

Peter Hill

For centuries, romantic and idyllic depictions of the weather, from sublime Swiss Mountain views to French Impressionist picnics on the river, have been superseded by the apocalyptic reality of climate change, global warming, and rising sea levels. I’m interested in your thoughts on this, and where it might lead?

Franziska Furter

I think we need to see and remember both to be able to continue, and not lose trust and hope. There was always beauty and destruction, chaos and order. But we definitely have to change many things to prevent mainly poor people from suffering and animals and plants from getting extinct. Do you know Friederike Otto? She is an amazing scientist who wrote a really interesting book called Angry Weather (2021).

I’ve also just read a great book by Gabriele von Arnim called The Consolation of Beauty (2023), but it may not yet be translated into English. It asks questions like “Can I still enjoy beauty and feel happiness while there is war, climate change and while the planet seems to be collapsing?”

So for me it is important to also talk about beauty with my work. I think often beauty says more about decay than decay itself.

Peter Hill

In her wonderful catalogue essay about your work for the Triennial, titled State of the atmosphere, curator Katharina Prugger describes how you had been collecting infrared images for your archive long before they wound their way into your work, and that the first time you used them was for a series of wearable scarves. I’m fascinated by artists’ archives and the many different forms they take. Can you describe your own archive please, and a side-question from the above is your relationship to fashion. Were the scarves a one-off, or have you created other weather-related fashion-wear?

Franziska Furter

I spend a great deal of my time on research. Or maybe I rather call it “having a sometimes focused, sometimes unfocused, gaze on the world, and letting myself be guided along invisible paths.” I am reading and listening to books and articles, looking at magazines and images, and I love recommendations by others. And when I think that there is a spark, I put it aside or make a note in my sketchbook. I don’t have an orderly archive where I could find specific things again. It’s more like a volcano which spits stuff out like lava every now and again. Other stuff gets lost forever. Sometimes I look at this spitted lava and an idea grows. With the infrared images of the hurricanes, it was the same. I have had them for years, and I tried several things, but it never worked until I did the scarfs, not as an art project, more for fun. Through thinking along the path of textiles I found the technique of tufting rugs and decided to make one by myself. One thing led to the other. I always find out what I want through making, through failing, through keeping on making. Failing is maybe the wrong word because it is only failing in the eyes of my former expectations, but often the unexpected is much more interesting.

Peter Hill

I’m writing a book called The Nomad and the Hermit (In all of us) reflecting both on my time as a lighthouse keeper and on the four-year Fake News and Superfictions worldwide lecture tour I was on, moving from one artist residency to the next—Berlin, Bali, Scotland, Sydney, Tasmania—all cut short by COVID in 2020. Then I went from being a nomad to being a hermit in lockdown. I was delighted to hear that you consider yourself a Nomad too. Can you expand on this, in any way you like, but perhaps also mention the changes in weather patterns as you traverse the globe?

Franziska Furter

I love doing artist residencies. They are very much part of my practice. I wouldn’t call myself a full-hearted nomad as I always had a ‘home’, a place to go back to, a place where I had my materials, my things and my books. This ‘home’ has changed three times within the last 20 years. I went from Basel to London, from there to Berlin, and a few years ago back to Basel. I think I do need roots. And probably a very long leash. I am just back from my three-month trip to Australia, and while I was there, I realised again that I rather stay at one or two places for some weeks and get to know the people and the surroundings, than move from place to place every few days. When I think about it now, it feels like in all the places I went to with a residency the weather was always very present…But maybe that’s just everywhere…nowadays.

Installation view of Franziska Furter’s work Liquid Skies/Gwrwynton display in NGV

Triennial from 3 Dec 2023–7 Apr 2024 at NGV International, Melbourne.

Photo: Lillie Thompson

Installation view of Franziska Furter’s work Liquid Skies/Gwrwynton display in NGV

Triennial from 3 Dec 2023–7 Apr 2024 at NGV International, Melbourne.

Photo: Tim Carrafa

J. M. W. TURNER

Falls of Schaffhausen (Val d’Aosta) (c. 1845).

oil on canvas

91.5 x 122.0 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with the assistance of a special grant from the

Government of Victoria and donations from Associated

Securities Limited, the Commonwealth Government

(through the Australia Council), the National Gallery Society

of Victoria, the National Art Collections Fund (Great Britain),

The Potter Foundation and other organisations, the Myer

family and the people of Victoria, 1973.