VOLUME

ISSUE 11

Emergency

Emergency as a contemporary idea is primarily borne out by sudden medicalized ruptures to the human body, severe political fractures to the body politic of society, and everyday breaks as a means to temporally attend to matters with a sense of immediacy, urgency. These ritualized signifiers form the basis on which one can help ascertain the current station of contemporary society.

ISSUE 11

2022

Emergency

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Exhibition

Essays

Conversation

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Emergency

Exhibition

Haunted by Catastrophe

Conversation

Art and Emergency

Pratchaya Phinthong, Milenko Prvački

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy Editor

Anmari Van Nieuwenhove

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Editorial Board

Professor Patrick Flores, University of the Philippines

Dr. Peter Hill, Artist and Adjunct Professor, RMIT University, Melbourne

Professor Janis Jeffries, Goldsmiths, University of London

Dr. Charles Merewether, Art Historian, Independent Researcher, Curator and Scholar

Manager

Sureni Salgadoe

Contributors

Chen Yun

Amitesh Grover

Ksenia Jakobson

Mahsa Aleph

Goran Vojnović

Zaki Razak

The Editors and Editorial Board thank all reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments and feedback to the contributors.

Introduction

Introduction: Emergency

Since 2020, ISSUE has had a focused response to the crisis of humanity brought about by the global COVID-19 pandemic. A polyptych of four volumes was organised. Viral Mobilities (Vol.09, 2020) focused on the Anthropocene as a “virus-vectorised community and economy.” This was followed by two unique volumes dedicated to art and performance. Tropical Lab (Vol.10, 2021) studied the impact of the pandemic on artist residencies and mobilities with a close study of Tropical Lab—an international art camp. Arrhythmia (Special Volume, 2022) looked at the impact and potentiality of isolation and determination, and severe implications for performance-making and embodied communal and social practices.

Vol.11 of ISSUE, themed Emergency forms the fourth dimension of the polyptych.

As a contemporary idea, an emergency is primarily borne out by sudden medicalised ruptures to the human body, severe political fractures to the body politic of society, and regular breaks to temporally attend to matters with a sense of immediacy and urgency. These ritualised signifiers form the basis on which one can help ascertain the current station of society. Humanity currently faces a pandemic, eviscerated by an increasingly simultaneous flow of newer emergencies from new and renewed diseases, ritualised lockdowns, political and memory wars, identity and equity battles, food security and supply chain blockages, climate changes, rise in the cost of living, etc.

Etymologically, words such as merge, emerge, emergence, emergency, immerse and submerge draw their primordial reference from classical Latin’s êmergere (to rise, bring to light). To bring to light (as Zaki Razak’s essay in this volume alludes) is an integral, if not existential, consideration for artistic practices. Through careful enquiries—scanned through past and current environments—art has been a beacon to proffer ways of re-thinking the world. However, with the increasingly shrinking mind-space in an information and social media-led world, artistic considerations are crowded with an urgent need to respond to everyday concerns besides pandemics, new nationalisms or environmental concerns.

This volume is significant in that artists and curators reflect critically to real-time issues. Ksenia Jakobson (Russia) curates Russian and Ukrainian artists in a first-ever book exhibition reflecting on resistance and artist expressions in an ongoing memory war. Chen Yun’s (China) lived experience during Shanghai’s 2021-2022 infamous lockdowns, form the backdrop of her photo-essay on artist response to the pandemic and its associated crisis management practices. As Amitesh Grover’s (India) allegorical essay draws attention to meta-fictive disappearance of images, Mahsa Aleph (Iran) reconstitutes installations on Iranian memory terrain. Zaki Razak (Singapore) and Goran Vojnovic (Slovenia) look inward to speak from a space within—within their unique everyday concerns while dealing with the pandemic. A conversation between three Southeast Asia-based artists provides an insight into the core concerns of being an artist today.

These contributions provide us with a way forward as to how to ‘speak’ to art and its new emergence.

Exhibition

Haunted by Catastrophe

The catastrophic shock awakens an acute awareness of the past. It triggers an understanding, albeit belated, of the linear order of events leading up to the calamity. What before was barely legible now reads loud and clear. Yet again, Walter Benjamin’s argument stands—events of the past gain their historical meaning retrospectively.1 And yet, every time such a moment of catastrophic clarity arrives, it comes as a surprise. As if suffering from a peculiar type of collective memory disorder, we are unable to make sense of the past. Long-term memory remains intact, but the recent past is not registered. Unable to produce new memories, we end up living in an endless now. Stuck in an infinite loop, we are doomed to repeat the past, and unable to imagine the future.

Back in the 1980s, Frederic Jameson characterised postmodernism by this very kind of historical amnesia.2 The postmodern subject, claimed Jameson, had lost their sense of linear temporality—the past, present, and future were replaced by a “series of pure and unrelated presents in time.”3 With no cultural forms capable of articulating the present, the endless now starts to resemble a composite in which the present is saturated with the past to the extent that it almost feels right. But it doesn’t feel right. Amid countless catastrophes layering upon one another, the endless now has slowly become an “end times.”4 For only today is guaranteed, never tomorrow—as Günther Anders once put it, speaking of the doctrine of mutually assured destruction.

Our task today is to fight this selective amnesia—to try to remember that the future was once possible. Perhaps it will soon be again. Since with each catastrophe comes the potential for historical rupture, the subversion of the order of things.5 Moments of regression hold a redemptive potential to reveal the contingency of historical order, and to open up space for new social configurations to emerge.

With this potential comes a demand—that the society that created the catastrophe progresses beyond it. And for that to happen, we will need to start remembering, learning, and mourning. We are haunted by the unprocessed trauma of the Soviet catastrophe. In turn, this trauma triggers compulsive repetition: “If the suffering is not remembered, it will be repeated. If the loss is not recognised, it threatens to return.”6

And it is back. We failed to do the work, to remember and to mourn, and today amidst the catastrophe brought on by Putin’s Neo-imperialist regime, we cannot afford to fail again. Only the impulsion to remember can overcome the compulsion to repeat.7

1 On the Concept of History

2 Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

3 Ibid. 27

4 Anders, “End-Times and the End of Time”

5 Diner 9

6 Etkind 16

7 Freud, Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through

References

Anders, Günther. “Endzeit und Zeitende (End-Times and the End of Time),” 1959. Translated excerpt from German by Hunter Bolin. In Apocalypse without Kingdom, in E-flux journal, Issue #97, February 2019, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/97/251199/apocalypse-without-kingdom/

Benjamin, Walter. “On the Concept of History.” Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 4: 1938-1940, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings. Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 389-400.

Diner, Dan. “Zivilisationsbruch: Denken nach Auschwitz.” Fischer, 1988. Translated in part as The Limits of Reason: Max Horkheimer on Anti-Semitism and Extermination from the book Beyond the Conceivable. California, 2000.

Etkind, Alexander. Warped Mourning: Stories of the Undead in the Land of the Unburied. Stanford University Press, 2013.

Freud, Sigmund. Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through (Further Recommendations on the Technique of Psycho-Analysis II). 1914.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press, 1991.

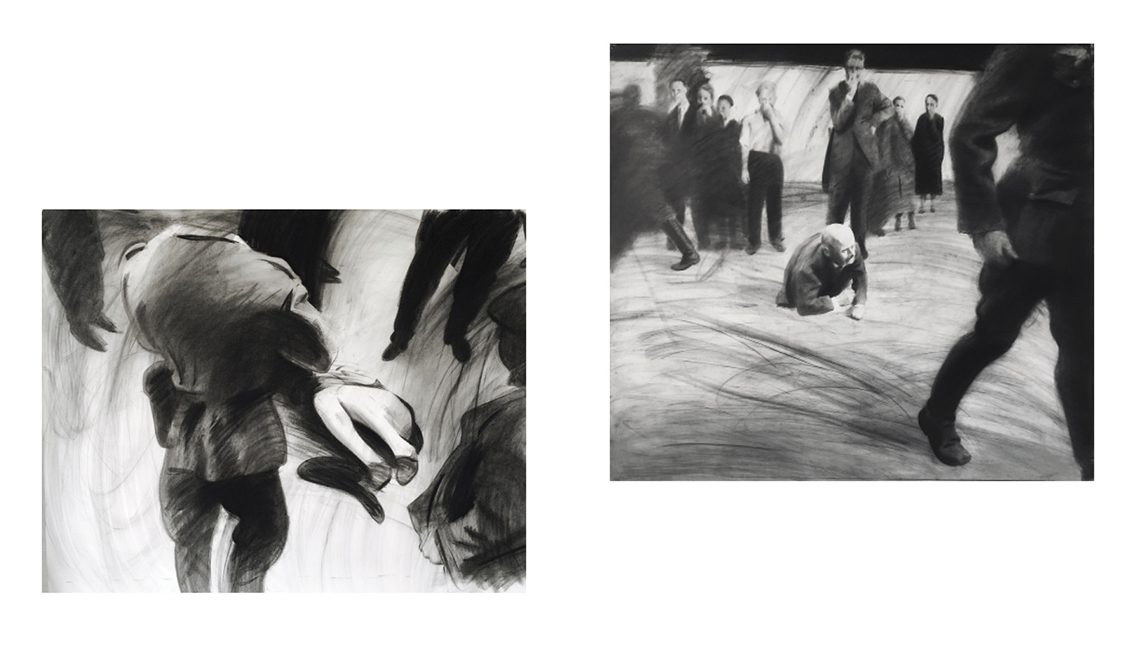

Nikita Kadan

Pogrom

2016–2017

charcoal, wash, paper

Courtesy the artist and Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN - Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie)

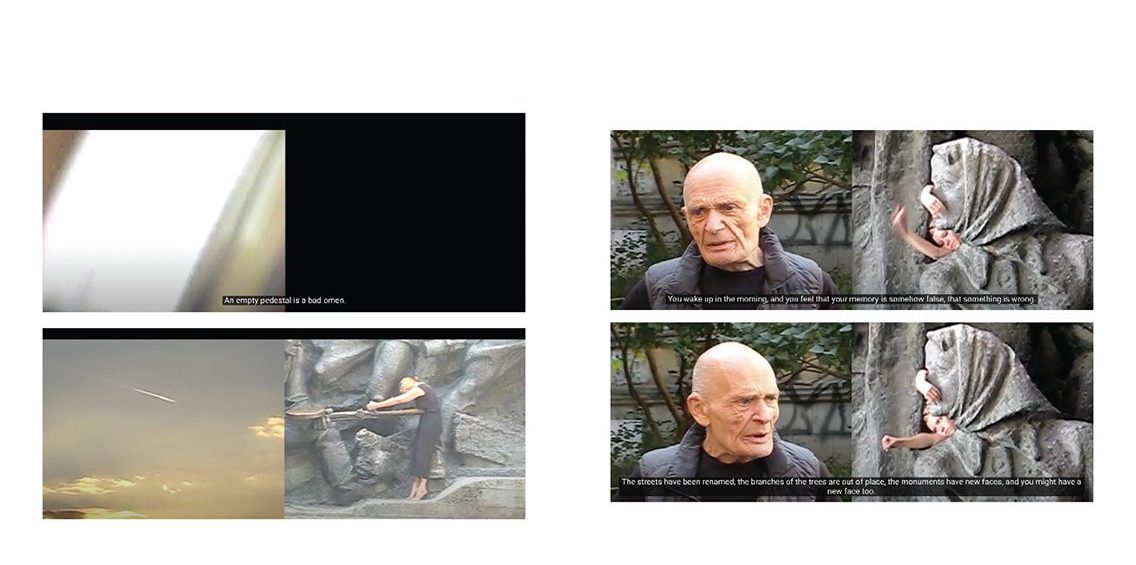

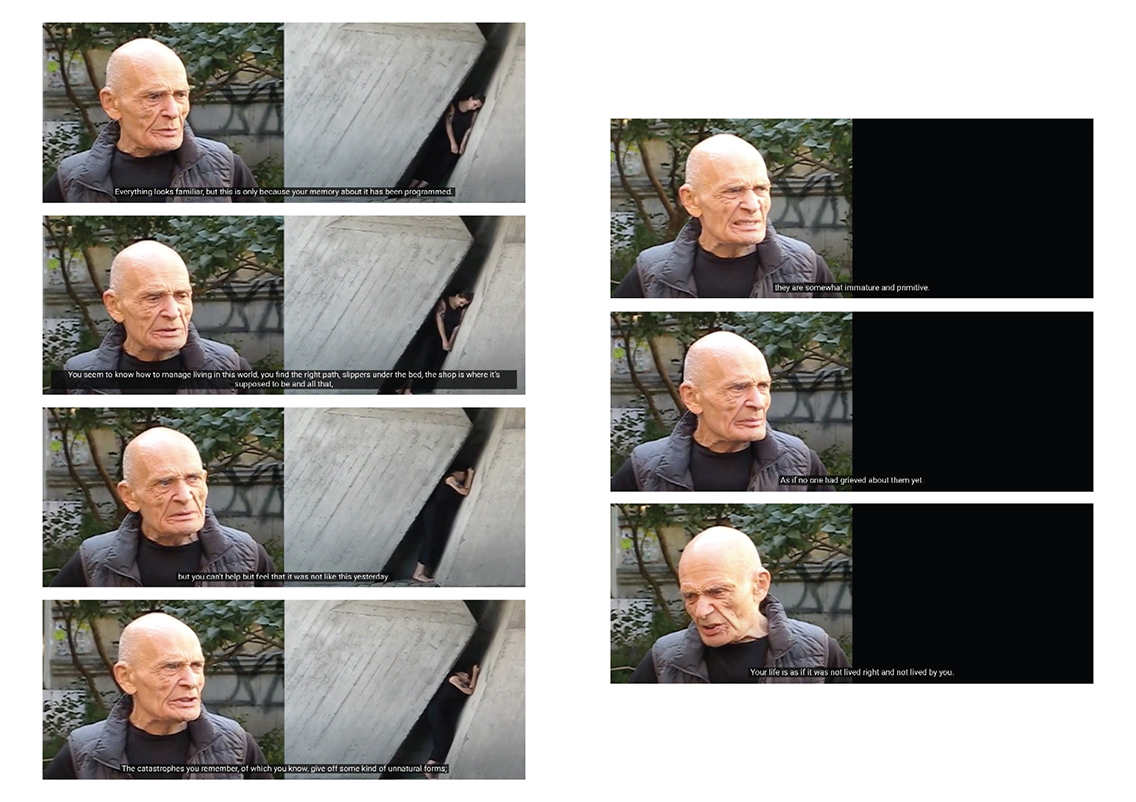

Dana Kavelina

There are no Monuments to Monuments

2021

2-channel video, 34:35min in colour, sound.

Courtesy the artist

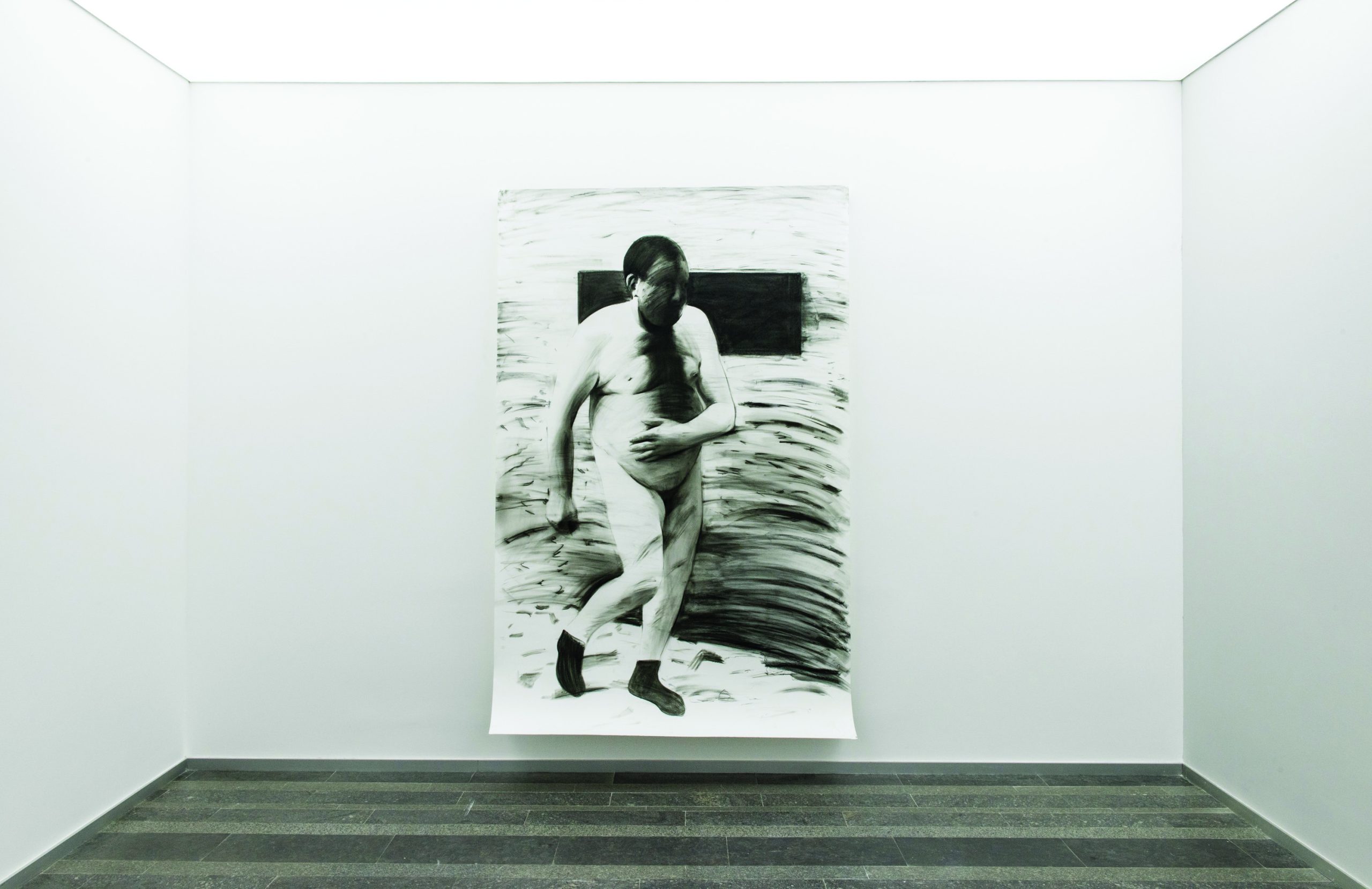

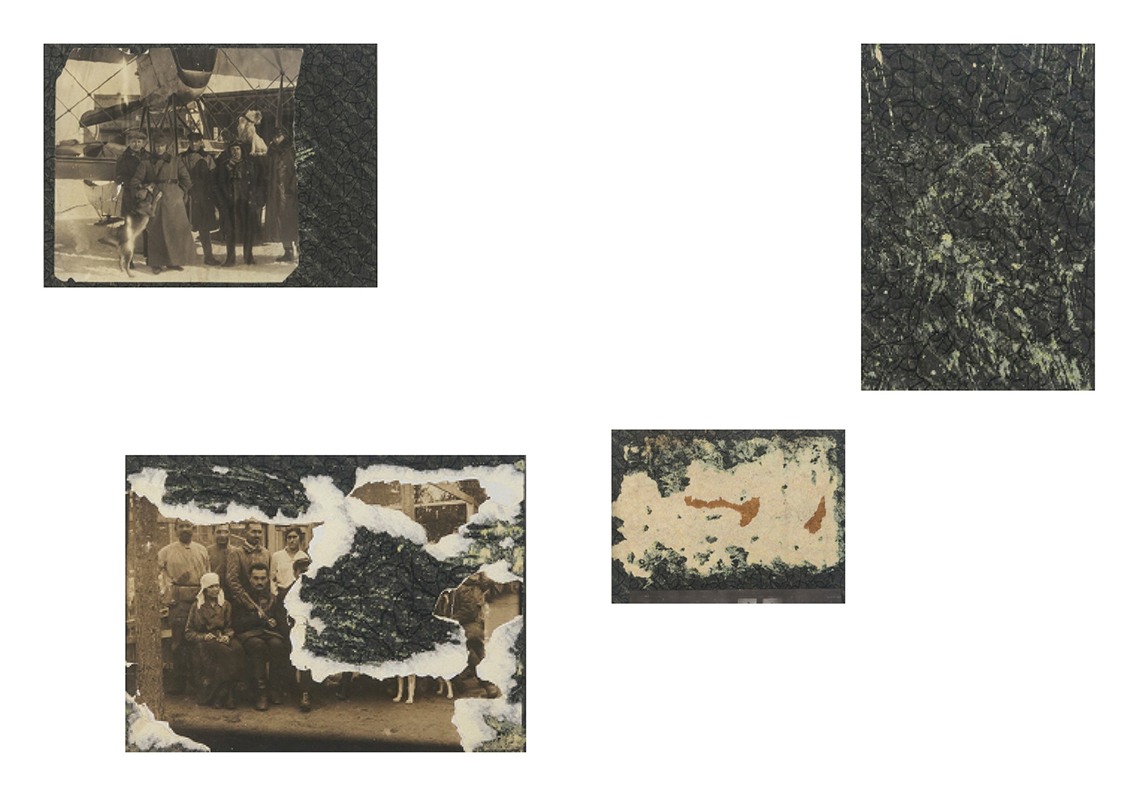

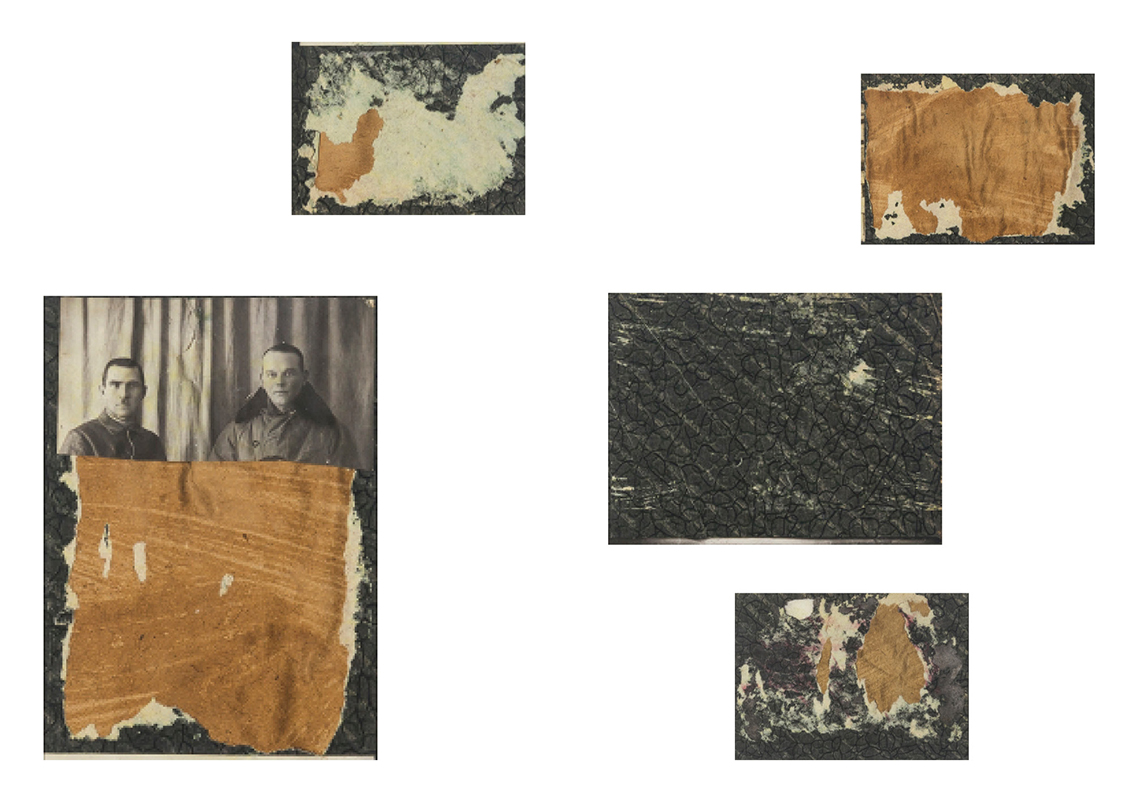

Mikhail Tolmachev

Pact of Silence

2016

22 c-prints

7-channel IR sound-installation

Courtesy the artist

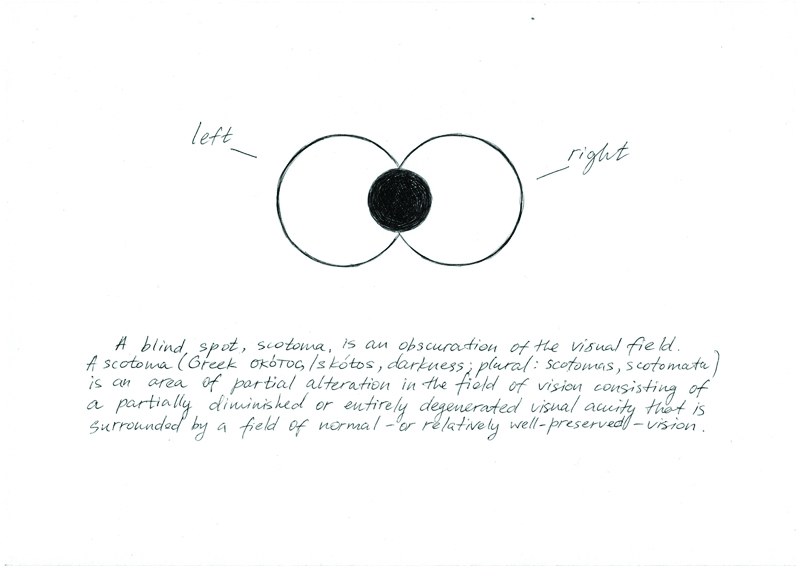

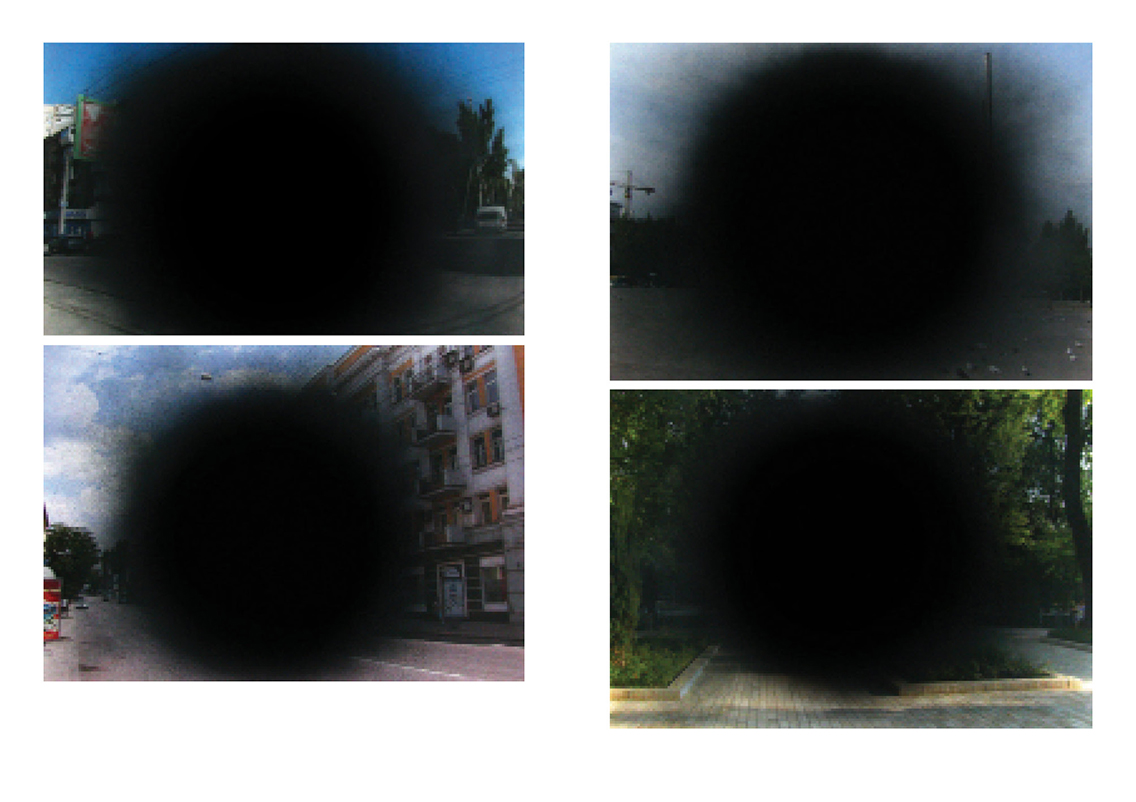

Mykola Ridnyi

Blind Spot

2014–2015

acrylic spray on c-print

42 x 59.4 cm each (8 of a series of 20 works)

pen on paper

21 x 29.7 cm each (2 of a series of 4 drawings)

Courtesy the artist

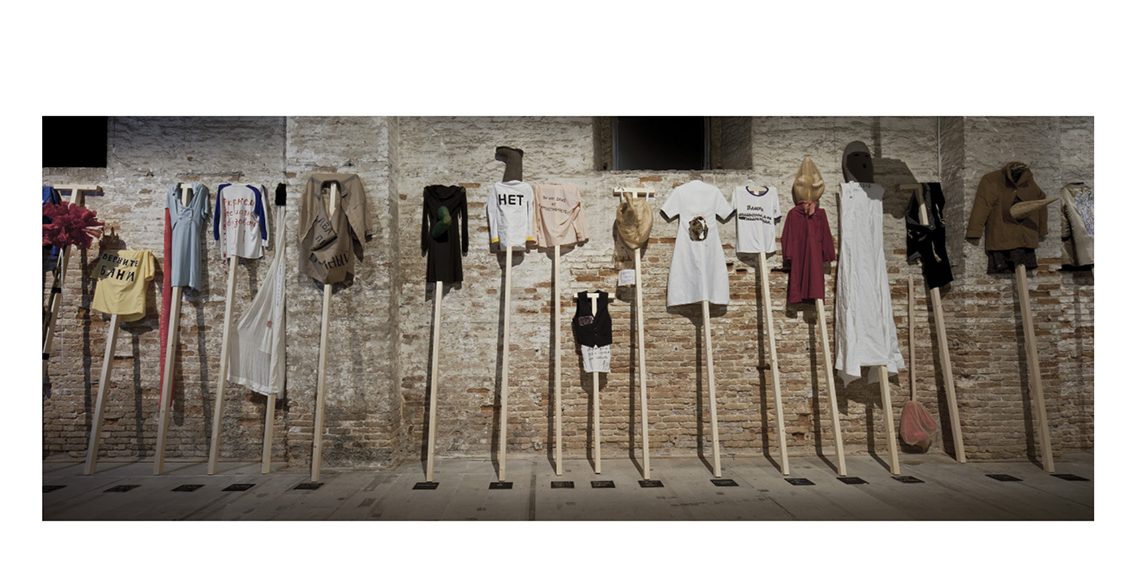

GLUKLYA /Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya

Clothes for the demonstration against false election of Vladimir Putin

2011–2015

textile, handwriting, wood

Courtesy the artist and AKINCI, Amsterdam,

Photo: Alessandra Chemollo; Courtesy of la Biennale di Venezia, with the support of V-A-C Foundation, Moscow

Lesia Khomenko

After the End

2015

A series of watercolours in box-frames under milk glass

Courtesy the artist

In December 2021, amidst yet another wave of political repressions, Russia’s Supreme Court ordered the closure of Memorial International—Russia’s oldest human rights group, founded in the late 1980s to document and study political repressions of the Soviet Union and present-day Russia. The decree was carried out under the “foreign agent” legislation, which indiscriminately targets organisations and individuals seen as critical of the government.

In the fall of 2011, the MediaImpact International Festival of Activist Art took place in Moscow as a special project of the IV Moscow International Biennale of Contemporary Art. The group exhibition, public lectures, and discussions had gathered a great number of local and international artists and activists. Performances and artistic interventions spilled out into the streets and public spaces of Russia’s capital. Just a few months later, the same streets had witnessed some of the biggest protests in Moscow since the 1990s.

I happen to have the catalogue of the MediaImpact festival, which I had conveniently ‘forgotten’ to return after borrowing it in 2013 from the St. Petersburg office of an international arts organisation I was working at at the time, thankfully, amid the frenzy of a “foreign agent” inspection, no one noticed that catalogue had gone missing. Flipping through it now in 2022, as the Russian army is bombing Ukrainian cities, as people in Russia are being arrested for even a slight suspicion of protest activity, to see the documentation of an activist art festival taking place in Moscow feels bizarre, almost unbelievable.

On the following pages are reminders of the recent past, when for a brief moment it felt like another future was possible, and perhaps soon it will be again.

Non-Governmental Control Commission, Vote Against All, 1998

Photograph

Courtesy the artist

Source: http://osmopolis.ru/protiv_vseh/gallery/a_138

Non-Governmental Control Commission, Barricade, 1998

Documentary film (released in 2015)

Courtesy of Russian Art Archive Network (RAAN)

Source: https://russianartarchive.net/en/catalogue/document/V1429

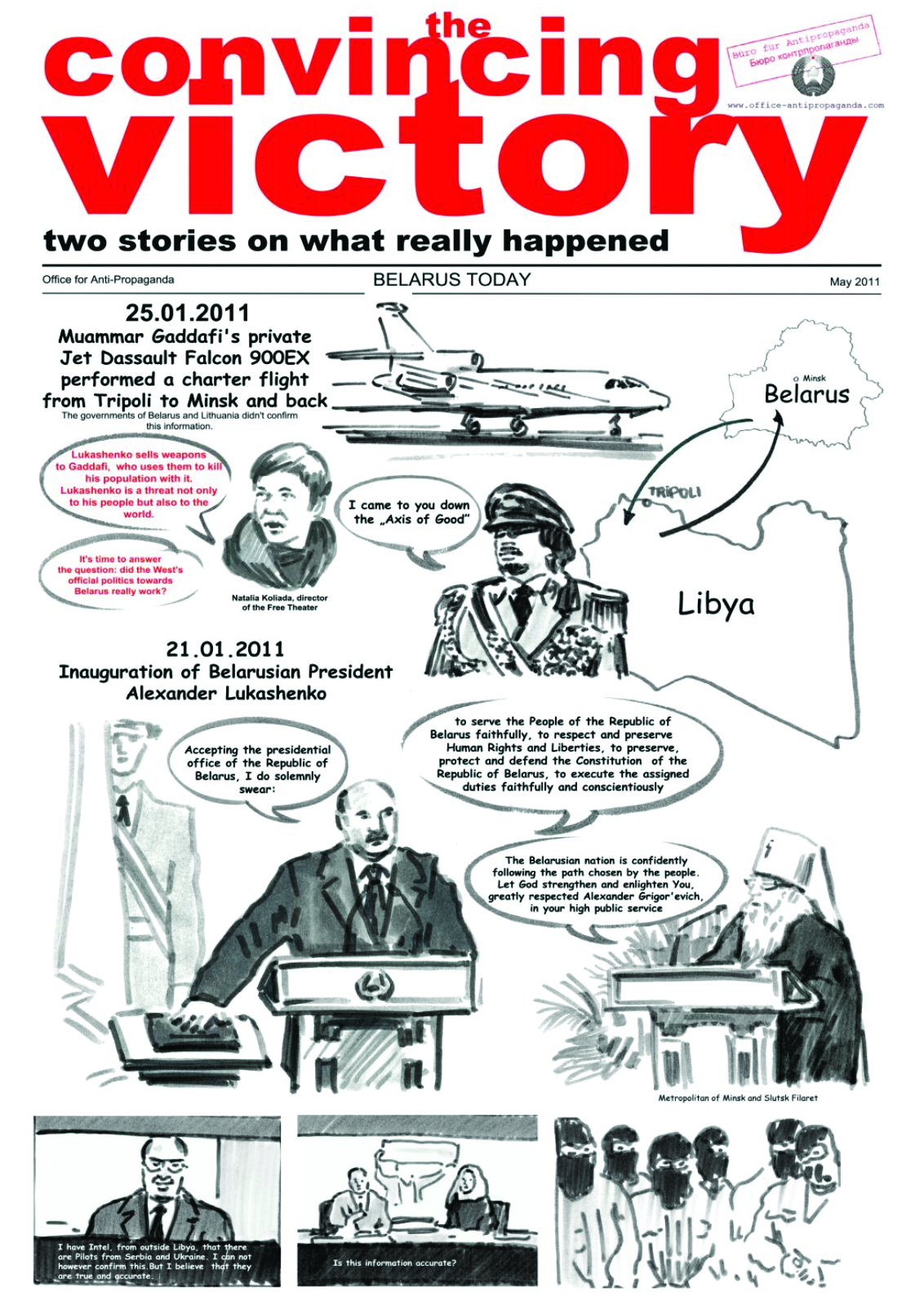

Marina Naprushkina, The Convincing Victory: two stories on what really happened, May 2011

Newspaper

Courtesy the artist

Note:

The 12 pages of the continued political comics illustrate how the situation unwound in Belarus after the

presidential elections in December 2010. All the latest developments—i.e. political repressions, balance-of-

payments and economic crises, a bomb attack in Minsk subway, etc.—are described from two viewpoints: the

first one shows how they are interpreted by the state propaganda machine, the other presents information taken

from independent mass media and blogs.

Oleksandr Volodarsky, Chemistry, 2013

Book

Courtesy the artist

Note:

Chemistry is a collection of writings and drawings that the anarchist Oleksandr Volodarsky kept while serving

time in a penal colony.

Yevgenia Belorusets, Mobilisation, 2012

Video, photographs, text

Courtesy the artist

Source: https://belorusets.com/work/video-mobilisation

Note:

“Whenever I’ve taken part in poorly attended protests, passers-by and accidental spectators have always looked on with undisguised surprise. At some point, it struck me that the demonstration’s subject and goals were meaningless—whether it was about education, labour laws, or brutal violations of human rights.

We invited people enjoying a day off in the centre of Kyiv to take part in a brief improvised protest, which was recorded in stills and on video cameras. The protests were held in advance of legal proceedings to determine the fate of two illegally imprisoned social activist-artists, Dmitry Solopov and Alexander Volodarsky.

Participants were invited to speak out in defense of the two activists, against anti-refugee discrimination, against the violation of prisoners’ rights, or against the criminalisation of political activism and imprisonment for minor offenses. They were offered several banners to choose from; they were also allowed to turn their backs to the camera or hide their faces. For the majority of participants, this was the first protest of their lives. Lots of people refused to take part, while a few of those who agreed only decided to take a stand on the condition that their faces could remain hidden behind the banners. In this case, perhaps the only reliable thing was the banner they held in their hands—like the last bastion, preserving them from the dangers of political life.” Yevgenia Belorusets

Matvei Krylov, You are not Alone, 2011

Cut-out board

Courtesy the artist

Note:

This cut-out board was originally designed for the exhibition Mokhnatkin (Artists supporting Sergey Mokhnatkin) in Sakharov Center. Russian artists had collectively organised a number of exhibitions, happenings, and Internet campaigns in support of the political prisoner Sergey Mokhnatkin who became an accidental victim of a long-lasting political struggle between the authorities and the opposition.

Victoria Lomasko, Chronicles of Resistance, 2011

Ink on paper

Courtesy the artist, Copyright the artist

Note:

“2012 was marked by heavily attended protests by the Russian opposition. For the first time since the early 1990s, the protest movement in Russia attracted worldwide attention. Many people anticipated an “orange” revolution... Beginning with the elections to the State Duma, on 4 December 2011, until November 2012, I kept a graphic ‘chronicle of resistance’ in which I made on-the-spot sketches of all important protest-related events. I will try now to recall and describe the protests, in which I was involved as a rank-and-file albeit regular participant.” Victoria Lomasko

Bombily Group, We don’t know what we want, 2008

Photo documentation of performance

Courtesy of Vlad Chizhenkov archive and Garage Archive Collection

Source: https://russianartarchive.net/en/catalogue/document/F5078

Note:

On May 1 2007—International Labour (Workers) Day, Bombily blocked Bolshaya Polyanka Street in Moscow with a six-metre slogan “We don’t know what we want.” Soon the group was detained by the police, and subsequently, the photo documentation was destroyed The performance was reenacted in the Tushino tunnel and

on Ivanovskoye highway on July 12, 2008. The action was held with the participation of the art group Voina and others.

Pasha 183, True to the Truth 19.08.91 Reminder, 2011

Screenshot documentation by author of life-size stickers of riot police over doors of Moscow metro station.

Source: http://183art.ru/putch/putch.htm

Note:

In True to the Truth 19.08.91 Reminder, the heavy swinging doors of the Krasnye Vorota metro station were covered with life-sized stickers of “OMON”—the Russian riot police. The title alludes to the 1991 Soviet failed coup d’état attempt by hardliners of the Soviet Union’s Communist Party to forcibly seize control of the

country from Mikhail Gorbachev.

Artists’ Bios

Yevgenia Belorusets (b.1980, Ukraine) is a photographer and writer. She is the co-founder of Prostory, a journal for literature, art and politics, and a member of the interdisciplinary curatorial group, HudRada. Her works move at the intersections of art, literature, journalism and social activism, between document and fiction. Her artistic method was established in her long-term projects such as Gogol Street 32, which portrays the residents of a communal apartment building engaged in their daily activities in a slowly decaying living environment. Another is the project Victories of the Defeated which comprised of a series of documentary photographs, texts and interviews, and was dedicated to the coal miner communities which continues to exist in Eastern Ukraine on the very edge of military conflict. To accomplish this work Yevgenia Belorusets visited cities near and in the war zone of Donbas Region in Ukraine between 2014 and 2017.

Bombily Group is an art collective created by the artist and curator Anton Nikolaev in 2004. Members include Anton “Madman” Nikolaev and Alexander “Superhero” Rossikhin, former members of Oleg Kulik’s studio. The name “Bombily” refers to a colloquial name for a private cab driver engaged in illegal taxi services.

GLUKLYA / Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (b. 1969, former Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, Russia) lives and works in St. Petersburg and Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Considered as one of the pioneers of Russian Performance, she co-founded the artist collective The Factory of Found Clothes (FFC) using conceptualised clothes as a tool to build a connection between art and everyday life and the Chto Delat Group, of which she has been an active member since 2003. In 2012, FFC was reformulated into The Utopian Unemployment Union, an inclusive project uniting art, social science, and progressive pedagogy, giving people with all kinds of social backgrounds the opportunity to make art together with the help of artist method embracing the Human Fragility. In 2017, Gluklya passionately threw herself into the research of the Integration Politics and its implications for newcomers, and for this purpose, rented a studio at the former prison Bijlmer Bajes in Amsterdam. The long-term project was concluded with the performative demonstration Carnival of Oppressed Feelings on 28 October, 2017, and presented in Positions #4 at the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven) in 2018-2019. Gluklya’s work Clothes for Demonstration Against False Election of Vladimir Putin has been presented at the 56th Venice Biennale of Art (la Biennale di Venezia) in All the World’s Futures, curated by Okwui Enwezor (2015).

Nikita Kadan (b. 1982, Kyiv, Ukraine) is a visual artist and activist who creates paintings, graphic works and installations. His pieces, often developed in collaboration with representatives of other fields (architects, sociologists, human rights activists), address collective memory and historical politics. He is a co-founder of the artistic group R.E.P. (Revolutionary Experimental Space), established during the Orange Revolution, and the curatorial-artistic collective HudRada.

Dana Kavelina (b. 1995, Melitopol, Ukraine) is an artist and filmmaker. She graduated from the Department of Graphics at the National Technical University of Ukraine (Kyiv). Her works have been exhibited at the Kmytiv Museum, Closer Art Center (Kyiv), and Sakharov Center (Moscow). She has received awards from the Odesa International Film Festival and KROK International Animated Film Festival.

Lesia Khomenko (b. 1980, Kyiv, Ukraine) is a multidisciplinary artist that reconsiders the role of a painting medium and constructs complex critical statements around it. In her practice, Khomenko deconstructs narrative images and transforms paintings into objects, installations, performances, or videos. Her interest lies in comparing history and myths, revealing tools of visual manipulation. She is co-founder of R.E.P. (Revolutionary Experimental Space) since 2004 and since 2008, a member of the curatorial group HudRada, a self-educational community based on interdisciplinary cooperation. She is a tutor, and a programme director of Contemporary Art at Kyiv Academy of Media Arts.

Matvei Krylov (b .1989 in Orenburg region, Russia) is a political activist and actionist artist. He works with poetry protest evenings and organised dissident traditions like Mayakovsky Readings, as part of his engagement with political issues. He had earned time in Buturskaya Prison, as well as the Alternative Prize of Activist Art.

Victoria Lomasko (b. 1978, Serpukhov, Russia). Drawing on Russian traditions of documentary graphic art, Victoria Lomasko explores contemporary Russian society, particularly the inner workings of the country’s diverse subcultures, such as Russian Orthodox believers, LGBT activists, migrant workers, sex workers, and collective farm workers in the provinces. Her work has appeared in Art in America, The Guardian, GQ and The New Yorker and in exhibitions globally, including at Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, Austria; Garage Museum, Moscow, Russia; GRAD at Somerset House, London, UK; and the Cartoonmuseum Basel, Switzerland.

Marina Naprushkina (b. 1981, Minsk, Belarus) is a political feminist artist and activist. Her diverse artistic practice includes video, performance, drawings, installation, and text. Her work engages with current political and social issues. Naprushkina works mainly outside of institutional spaces, in cooperation with communities and activist organisations. She focuses on creating new formats, structures, and organisations that are based on the capabilities of self-organisation. In 2007, Naprushkina founded the Office for Anti-Propaganda that concentrates on power structures in nation-states, often making use of nonfiction material such as propaganda issued by governmental institutions. Starting as an archive on political propaganda, the “Office“ drifted to a political platform. In cooperation with activists and cultural makers, Office for Anti-Propaganda launches and supports political campaigns, social projects, publishes underground newspapers.

Non-Governmental Control Commission was founded by Anatoly Osmolovsky in 1989. Anatoly Osmolovsky (b. 1969, Moscow) lives and works in Moscow. He is an artist, theorist, curator, teacher, and one of the founders of Moscow Actionism. From 1990 to 1992, he was leader of the group E.T.A. Movement (Expropriation of the Territory of Art). In 1992, he became editor-in-chief of the journal Radek. In 1993, he formed the group Nezesüdik and In the late 1990s, he created the group Non-Governmental Control Commission. In 2011, he founded the journal Base and the institute of the same name.

Pasha 183 (1983–2013, Moscow) also known as Pavel 183, was a Russian graffiti artist based in Moscow. His work often carried social critically engaged messages over public structures, and he was best known for his grayscale photorealist spray painting.

Mykola Ridnyi (b. 1985, Kharkiv, Ukraine) lives and works in Kyiv, Ukraine. He graduated in 2008 from the National Academy of design and arts in Kharkiv, where he got his MA degree in sculpture studies. Ridnyi combines different artistic activities: he is an artist and filmmaker, curator and author of essays on art and politics. He is a founding member of the SOSka group, an art collective based in Kharkiv in 2005. The same year he co-founded the SOSka gallery-lab, an artist-run-space in an abandoned house in a centre of Kharkiv. Under Ridnyi’s lead, the gallery-lab was instrumental in the developing the artistic scene in the region before it closed in 2012. He curated a number of international exhibitions in Ukraine, among them After the Victory (CCA Yermilov centre, Kharkiv, 2014); New History (Kharkiv museum of art, 2009); and others. Since 2017 Ridnyi is co-editor of Prostory, an online magazine about visual art, literature and society. In 2019 he curated Armed and Dangerous, a multimedia platform that brought together video artists and experimental film directors in Ukraine. Ridnyi works across media ranging from early collective actions in public space to the amalgam of site-specific installations and sculpture, photography and moving image which constitute the current focus of his practice. In recent films he experiments with nonlinear montage, collage of documentary and fiction. His way of reflection social and political reality draws on the contrast between fragility and resilience of individual stories and collective histories. His works are in the permanent public collections of Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Ludwig Museum in Budapest, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Arsenal City Gallery in Bialystok, V-A-C foundation in Moscow and others.

Mikhail Tolmachev (b.1983, Moscow) is a visual artist who investigates alternative documentary practices. He is looking for aesthetic strategies to explore various constructions of reality and how they form temporality, space and agency. With installations, photo etchings, and spatial interventions he examines the intersections of realism and imagination, technology and territory. Mikhail studied documentary photography in Moscow and Media Arts in the Academy of Visual Arts Leipzig. For his work he extensively collaborates with architects, writers, sound-engineers, poets and historians. Mikhail‘s work was presented internationally, at the Kyiv Biennial, Tate Modern, Moscow Biennial, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, MUSA Vienna and Kunstverein Karlsruhe amongst others. He is based in Moscow and Leipzig.

Oleksandr Volodarsky (b. 1987) is a Ukrainian left-libertarian political activist, publicist, performance artist, and blogger. In the past, he was a member of the independent student union Direct Action, the Autonomous Workers’ Union, and the All-Ukrainian anarchist association called the Libertarian Coordination. He is a programmer by profession. From 2002 to 2009 he studied in Germany and since November 2009 he has lived and worked in Kyiv.

Essays

All That We Saw

It was sometime last year that the news of a mysterious event began to trickle in. By early this year, it had become a topic of intense discussion amongst photographers, archivists, hobbyists, and almost everyone who kept and looked after vintage photographs. Very soon, it became obvious that what had been predicted in fictional stories, in Sci-fi that dealt with the existence and proliferation of low tech and analogue pasts, was shockingly precise and prescient. Images were beginning to disappear.

No one quite knew exactly when, or how, it began. But one after another, news of mysteriously vanishing photographs appeared on social media. Old photographs began to show bizarre signs of erasure before the new ones did. At first, we dismissed it as a hoax; as yet another cheap stunt by the conspiracy-loving fringe to gain traction online. But soon, big tech and media began to report the inexplicable event that started somewhere in a small, quiet town, and soon spread across territories and borders across the world, like a virus.

From archives across the world, stacks of newspapers, the walls of galleries and museums, in warehouses, personal albums and smartphones, photos had slowly and permanently begun to vanish. Their ink, their colour, their imprint had begun to evaporate, and it left no trace behind. Photos were becoming irretrievable, somehow. The hanging frames were getting emptier; albums were turning despairingly pale; digital files were turning corrupt. There seemed to be no order, nor pattern to this inscrutable event. Within months, this mysterious contamination had spread across all continents, leaving millions of frames barren, walls empty, folders vacant, boards bare, exposing what the people in the photographs had masked with their presence—furniture, trees, curtains, fruits, sky, appliances, waterfall, wires, mountains, billboards, rain, the horizon.

This devastating phenomenon unleashed mass hysteria and public chaos, leaving millions in shock, distress, and disbelief. There were those who turned to scientists to explain the riddle of this disappearance, while hoards of people turned to shamans, priests, and religious books for answers. People found it difficult to stop mourning this incredible and unprecedented loss—of the past, of all times imaginable. The photo of an inconsolable young girl refusing to let go from her arms an empty, bare photo-frame is arguably the very last image the world saw. And that was the end of it—all gone!

Why had the images disappeared?

They say that it started as a tiny speck of contamination in the digital wild before it passed through hundreds of millions of computers and smartphones trailing havoc upon being downloaded into our systems, our devices. At the time of writing this, almost all of the 21.5 billion interconnected devices are infected by this virus. Whether it is a virus or not is not known yet, but if it is, its total weight, all of it circulating and residing on our devices across the world, could be collected to make a mound of dust to keep in no more than the palm of my hand. It didn’t make anyone sick—thank God for that—but it brought in its wake another kind of illness, an illness for which we have no word, yet.

Why had the images disappeared?

They say that the images were all damned to vanish from the start; they were meant to darken over time. Silver salt, asphalt, mercury, copper, all the plates and later, the pixels, carried the exact same annihilation date. Their expiry was encoded into the exquisiteness of every image, because, as some knew, light when molten into ‘form’ and ‘shape,’ frozen in a frame, was bound to burst into flames one day. And, that day was upon us. How are we to resolve the pain of love living in the absence of images? How are we to reconcile with the utter absurdity of our existence, in which we are now cursed to live, forever, in the terror of the present?

Why had the images disappeared?

They say that the ghosts of all the dead people, which lived in photographs, had longed for freedom. They had yearned to escape the visible level in which they had had the misfortune of being arrested in. It took them decades of struggle and labour to establish ‘hearing routes’ between photographs, an intricate web of listening threads, invisible to the naked eye, which helped them find common cause in their misery, and gather momentum to burst through the images together, all at once! Many people claimed that they witnessed an apparition when it happened: Spectre, a spirit, a shadow leaving the photograph in front of their eyes, freeing itself from its captivity. Not every figure appears to have left its picture in the same manner. Some took off screaming like a banshee leaving the slipstream of a speeding train; some bleached and got washed out; a few others pixellated into a block of colour before departing; others, melted and dripped away.

Why had the images disappeared?

In an ethnographic research done a few years after the phenomenon, it was found that people did not believe in the disappearance of images to be an aberration or a mystery. They saw the ‘death of images’ as a divine intervention, an automated reprieve requiring no explanation nor extensive investigation. Mechanisms of control like personal data, CCTV surveillance, biometrics identification, face-recognition, electronic frisking, device-searches and others frequently produced situations where anxieties would run high, rules would break, and violence could occur. The rules of circulation—where, how, and when to share images, or how to associate with them—were too elaborate and constantly shifting that people were bound to break them at some point or the other. Most people had suffered from or witnessed “image-violence,” a term that had become commonplace for violence that was inflicted in, through, or as a consequence of images. This violence often took the form of beatings or other cruel bodily punishments.

Many reported that they had, at several points in their lifetimes, barely escaped death at the hands of the police, or sometimes a mob, because they couldn’t explain the presence of a certain image in their phone, in their house, or in their wallet. This nerve-wrecked society had actually produced a population which was no longer able to understand what an image was—noone was able to describe any image anymore, nor wished to for the fear of being beaten. By threatening people with death in this way, everyone had begun to deny the existence of images to escape this condition of a subjugated life. The society’s material infrastructure exacerbated this precarity of life. Image-violence was often administered at points of contact composed of a dense architecture of stationary and mobile establishments. Over time, public and private infrastructures began to align itself to further this kind of subjugation with highways, bridges, roads, streets, and airports becoming “dual-purpose” spaces of circulating images and bodies, and also of arresting images and bodies that did not align with each other. Until one day, all images disappeared, leaving no trace in data, no residue in the massive server farms that contained them. The image died—they tell it like a folktale—so people could continue living.

Why had the images disappeared?

They say that a great dictator had ordered a restructuring of the world. In the new world, he wanted us all to begin again, afresh, from a clean, imageless start. A group of extremist vigilantes carried out a series of image-destructions, especially of photographs that displayed an “anti-patriotic spirit.” Enthusiastic crowds chanted and witnessed these burnings—they started with setting fire to many well-known photographs at public crossings and intersections, but later, and puzzlingly so, they continued to do it in the privateness of their homes as well. The largest of these bonfires occurred in a city not so far away, where an estimated 40,000 people gathered to hear a speech by a propaganda minister, who declared that the new shining world can become manifest only when the debris of the past is cleaned up. The response to these burnings was immediate and widespread. Gripped by fear, people began destroying all photographs in their possession without mercy or thought, and as they did so, they pretended—to each other and to themselves—that they had little volition in carrying out this brutal act of destruction. They were convinced that the photographs had caught a plague, and needed to be set aflame.

Why had the images disappeared?

Guards stationed outside a museum in my hometown shot dead the chief archivist of images one day. I did not witness the event, but I vividly remember how his death was described. He was a middle-aged, scraggy person with a sincere demeanour about him, but he suffered from a mental illness. His condition sometimes caused him visual hallucinations and other forms of sensory misperception, all of which brought with it acute pain. During moments when his pain would become unbearable, he would run out of his office and wander the streets. The evening he was shot, he had walked deliriously and come unusually close to one of the guards stationed at the entrance of the museum.

No one had come to ask about his dead body up till late that night, so his body lay in the museum’s morgue (assigned for mummies) unclaimed. The next morning, in news, we heard several accounts of the shooting. People were angry with the callous way in which the guard had shot him, but beyond privately simmering in impotent rage, no one knew what to do. Many indirectly blamed the archivist for not being able to find a cure of his hallucinations. A day later, when they re-opened the museum to public, they realised that the images had gone missing from its walls. The frames were there, hanging right where they had been all this while, only the images had gone missing from within them. Not one frame, whether up on the walls, or in the cellar downstairs, showed any image that it was meant to possess. The museum director called her colleagues in other museums across the city, and they all reported the same inexplicable incident —the collection of images had vanished overnight. Not stolen, not erased, not rubbed off, not burnt; images had become air. It was as if the walls, the windows, the doors were all in place, but the building of the museum itself had evaporated. No one knew how or where to begin looking for the collection that was worth millions. And this phenomenon gradually spread to all images that existed in the world. The body of the image archivist still lies unclaimed, though.

Why had the images disappeared?

They say that the age of the Great Collapse is upon us. Photographs had retained a certain power that was no less than sorcery: Otherworldliness. A photograph made accessible that which was impossible to see with the naked eye—a technology of bringing the unconscious to the fore—and in doing so, brought uncountable worlds into existence, worlds that ought to have had been left, perhaps, undiscovered. The quantum spectrum of time—our time, in which we exist—had become overburdened with the presence of too many worlds (an eternity!), and this excess baggage needed to be shed, to be strewn across the space in the dark out there, be flung to other worlds and galaxies, where it might belong, in an effort to help this luggage find its rightful place in the universe, where it belonged—elsewhere. We needed to live lighter, in our being, on our planet, without the hope for eternity.

Why had the images disappeared?

Right before the image crisis, a group calling itself “Metaphor Army” had been holding weekly demonstrations in front of the State Theatre. The group’s core initiators were also involved in a previous occupation of the Opera House in protests against the extensive use of screens, projections, painted curtains, and visual technology that had come to dominate culture. This radical new group continued to attract a mix of people including conspiracy theorists, subterfuge aficionados, and self-declared fascists. The demonstrations became increasingly aggressive as shows in the theatre continued with state-of-the-art infrastructure, attracting attendees in large numbers to the performing arts experiencing a resurgence after the pandemic. The demonstrators had ignored social distancing measures and even attacked members of the press alleging that the coronavirus was a mere pretext, a scam to upend democracy, and to keep members of public glued to screens, to (fake) images of other people.

As the demonstrations in front of the state theatre gained momentum, the Metaphor Army started campaigning for an ‘image-less world,’ arguing that the current culture had become obsessed with “showing everything” (intimate acts like kissing, having sex to show passion; bareness of the body to show nudity; photo/statue of God to show the divine) leaving little to the imagination. “There was, it is to be said, just too much artistic freedom!” said the demonstrator’s leader in his conclusive remarks in an interview. “Many people seem to have a deep yearning that someone will take them by the hand and lead them somewhere, where there is no need to see. A place as pure as the ancients had built; a sacred place where there is only light (but no images); a holy place where the only thing to see is to look within.” This “mania of the middle-aged people” as the young began to describe it, led us to the rhetoric of the militant anti-imagers and other conspiracy theorists for whom every photographer was a criminal, every viewer a stray child who needed to be reined in. Young activists resisted the Metaphor Army all they could, but in the end, the elders won and managed to stamp out every image with their hardened religionism.

Why had the images disappeared?

They say that an old woman who sits knitting on the moon had begun to chew on images one night. She ate them all, one after another, over a long night of darkness, stuffing her mouth, her belly, ingesting them with body fluids that had taken a millennium to build. And when she was done eating the last image, she self-combusted from the terrible intensity of light that a trillion images had contained in them. And since, moonlight has been nothing more than the light of all our pictures that are lost to us now, shining down back on us, every night.

Why had the images disappeared?

They say that it was not the images that had disappeared, but our own sight. Somehow, we have all gone blind—the horror of it! This was a sickness of sight that had been waiting silently, showing little symptom, gnawing at the optic nerve, at its health, raising its pressure ever so slowly that we didn’t notice, eventually to a degree that was abnormally high. It was not the images, but humankind that was the cause of its own blindness. The disappearance of images was only the beginning of this fateful affliction, the first stage of an outcome that will manifest as the infliction of total and utter darkness. Some remembered the wise words that were uttered once, long ago:

You have never looked enough

upon that you ought to have looked

upon. To have eyes, and not see

our own peril? Eyes, they cannot see

what truth hides in the world. Only

when they are gone—the sea in your skull,

it might see better;

the true blank in your eye.

In the absence of the image, and worse, if we are indeed losing our sight progressively, how do we retain the power of seeing without being considered delusional by everyone around? If we are to survive in the future as a civilisation and as cultures, now is our moment to find ways to restore our ‘real’ sight, and in doing so, restore a future for the image. Because, if we don’t, we wouldn’t know how else to remember anything. And so, we must begin preparing for it. We must begin by reaching into the recesses of our collective and individual minds to inquire how photos take root, and call upon ourselves as witnesses of images, as mental archivists, as contemplative nodes in the memory of a collective, and as participants in the act of restoring the image.

(November 2021/June 2022)

This piece is an expansion of an essay originally written for the Chennai Photo Biennale Journal in December 2021.

27.94 x 27.94 cm

Photo Rag Paper, Ink, Wood, Glass

Essays

Emergencies, like most human phenomena, repeat themselves. Sometimes, they repeat in the same place in another time, or in another place at almost the same time. However, they also repeat themselves in an imperceptible form that essentially emerges out of the same but hidden structural mechanisms. When they do repeat or show up again, it may be shocking to those who do not recognise their earlier incarnations; maybe because such emergencies do not evoke sharp consciousness or memories of images or sounds in a daily life-flow—when time passes smoothly and individuals do not experience the time and space of this emergency collectively—thus the boundary of a daily emergency is limited to the personal space and do not travel across other domains. They are also not documented in a way to be remembered and recognised in the future as an emergency, or a memory of an emergency.

Emergencies in an urban setting like Shanghai, with a population of 250 million, bear all the above features.

Photo by Chen Yun, 2005

On a sunny day in 2005, a young man sitting in a bench reading his mobile messages (in an era before smart phones) while a sculpture of the famous author Ding Ling (땀줬) sat next to him, reading a book.

For a term paper, I paid several visits to Duolun Road, a street in Hongkou District, in north Shanghai in the autumn of 2005. The street has been known as Duolun Road Cultural Celebrities Street since when I was in high school. This long title, though sounding a bit odd in English, makes good sense in Chinese and has been established over the years. In fact, the widening of this once narrow pass was a result of demolishing earlier houses and architectures. After the transformation, the street was made pedestrian-only and new sculptures of famous literary figures (or cultural celebrities) were set up to commemorate the left-wing literary movement once happened here in 1920s and 1930s.

Duolun Road (뜩쬈쨌) was constructed in 1912. Its original name was Darroch Road (注있갛쨌), after the British missionary John Darroch (1865-1941), who fled to China like many foreign missionaries in the early 20th century and later purchased this piece of land to attract investors and businesses. Although this road and its surrounding neighbourhood theoretically belonged to the Chinese settlement, it was built as one of those extra-settlement roads by the colonial government of Shanghai Municipal Council (1854 - 1943). As people could build houses without planning permissions, the road was soon filled with villas of exotic styles, in lanes paved by developers and businessmen.

The convenient location of this area and the relatively cheap cost of housing made it easier for a particular kind of writers and artists to live and work here. It is next to the major Japanese settlement in Shanghai (Japanese residents who had migrated to Shanghai continuously since 1870s) and was filled with numerous cinemas and publishing houses. The most well-known group is called The Chinese League of Left-wing Writers, a progressive literary organisation spearheaded by Lu Xun. It was by then an underground literary group, active between 1930 to 1935.

That summer of 2005 the street looked quiet and beautiful. It was by no means a busy street. In fact, it was much quieter than any of its narrow backstreets. In one of my chats with local residents, an old gentleman complained that the newly paved surface of Duolun Road made it extremely slippery for cyclists and pedestrians; one could simply stand at the iconic L turn of the street and witness them falling down during rainy days. Residents recall the old surface of this road, made of tiny pebbles and stones cast in mud, when falling raindrops over this surface added to the rhythm of traffic. People hardly fell down on Duolun Road in those days.

Eleven years later in 2016, Shanghai Biennale was curated for the first time in its 20 years of history by a non-Western international curator/group Raqs Media Collective (based in Delhi, India), and I was invited to join the curatorial team. I proposed to curate a project called 51 Personae, an off-site programme consisting of 51 events in the city of Shanghai based on the life experiences and potentials of ordinary people. An open call was announced on the Labour’s Daily (the official newspaper of Shanghai Federation of Trade Unions) on 5 May, days after the International Labour Day. It occupied half of a full page in the Culture and Sports section.

From the first month of 2016 till the beginning of the 11th Shanghai Biennale in November, we have been busily looking for the potential “personae” around us. Open call is one way (although 80% of the applications are from artists with their standard proposals of their works for an exhibition) and personal channels seem to be no less important than the public channels. One day, I was told by a friend of an artist, Eileen, who has recently moved out of her rented apartment in Jingyun Li, Hongkou District. She had sublet from Ms. Cheng Shaochan (넋紹窄), who was also given notice to leave the building. He briefly described Eileen’s situation to me, and it seems to be a typical story of demolition. A major difference is that this occurred in Jingyun Li, an area famous for being one of the former residencies of Lu Xun and his left-wing writer friends and the conserved neighbourhood architectures. Then, why was Ms. Cheng forced to relocate? I have been observing and interviewing such cases in Shanghai since 2013 and I strongly feel that such an ongoing story should become one of 51 Personae’s, so that it could be staged, learnt, told, discussed, and documented. Not as part of an official documentation or archive but a story that can be participatory and fluid in its approach. This for me is what 51 Personae as an art project should accomplish.

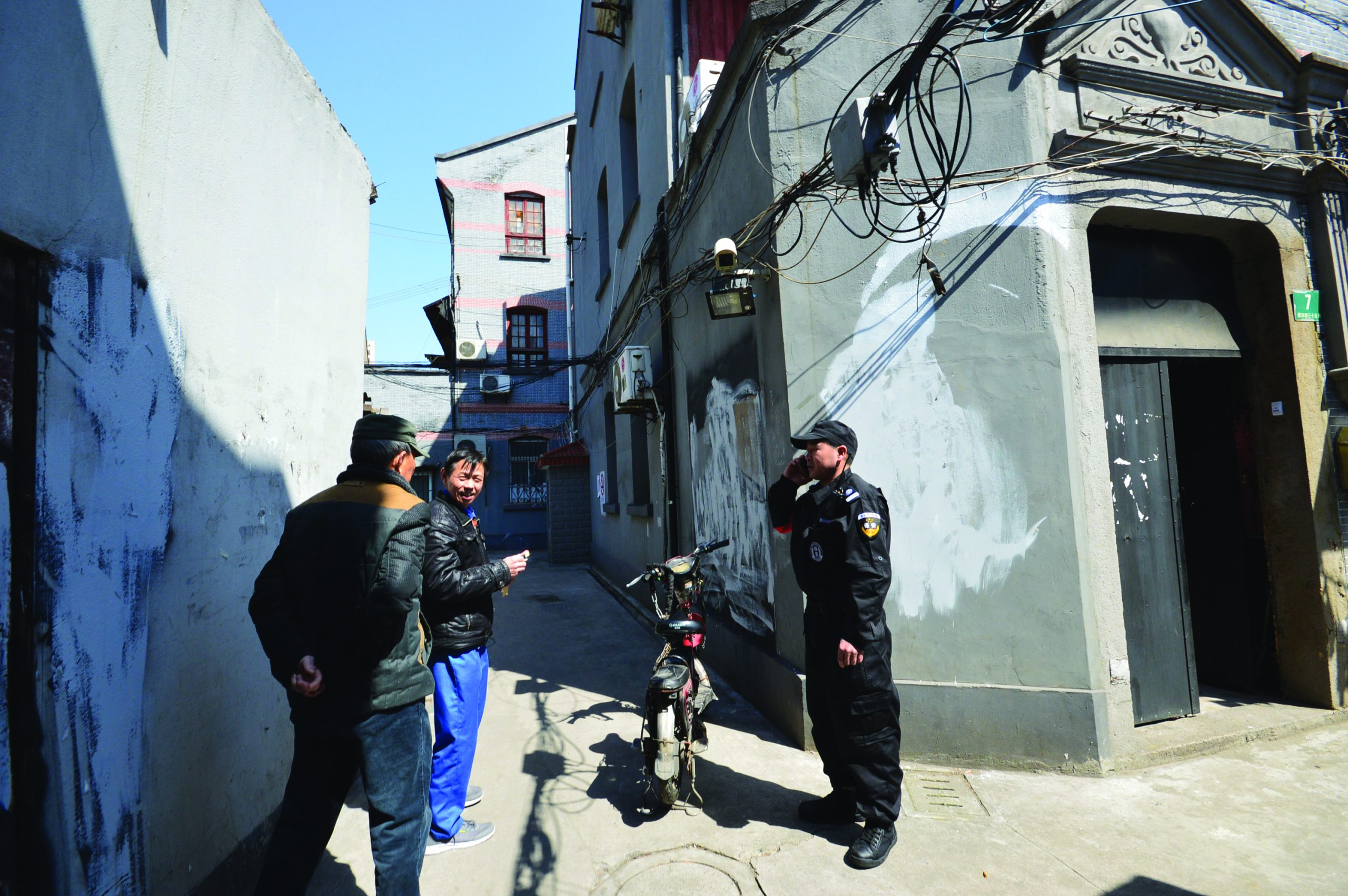

Photo by Chen Yun, 23 August 2016.

With the help of Eileen, I made an appointment with the owner of the house, Ms. Cheng. Ms. Cheng expressed her interest in 51 Personae even before we met. On 23 August 2016, Eileen and I took Shanghai Metro Line 3 and dropped off at Dongbaoxing Road Station and walked through a ruin which was once a vivid neighbourhood since 1920s. Metro Line 3 is an elevated metro line that shares the route with Songhu Railway (1876 - 2000) in its northern passage and it is exactly this railway that brought prosperity to Duolun Road, North Sichuan Road and Jingyun Li. The railway served as an infrastructure attractive to residents and developers in the 20th century, just like metro lines will increase the price of real estates along its line in the 21st century.

On that summer day, we walked through the “neighbourhood” right at the back of Duolun Road. It did not look like the neighbourhood as I had known back in 2005. The once crowded small streets are deserted except for a few people who seem to be stragglers of the land acquisition or simply who were in the business of recycling the materials and taking over the land for their employers. I wondered what Lu Xun and his friends would feel if they had lived till today. Lu Xun passed away in 1935, before the next page of Shanghai and China’s history. Since most of the houses were constructed with wood and bricks, the demolished materials were recycled back into bricks and wood structures, particularly those used as beams and pillars, which will be collected and sold to third parties—part of the demolition economy.

Photo by Chen Yun, 23 August 2016.

Ms. Cheng, in her late 50s, now lives in a small bedroom on the second floor, sparing the larger rooms for her tenants (one was Eileen who had just moved out, and another girl who lived on the third floor whose belongings were later removed from the house along with the belongings of Ms. Cheng). She now spends half of her time in Shanghai and another half in Minneapolis, where her son lives. The interior layout of this three-storyed Shikumen (literally stone gate) house was largely unaltered, keeping to its original structure, except for the position of the staircase which she shifted from the back door to the front—which she later felt was not an ideal change in terms of fengshui. However, this staircase later served to stage the 51 Personae event.

Before she purchased the house, it had been used as a dormitory for workers in a small factory. Before 1949, she heard that the house belonged to a musician and his family. Like many private houses, this one was obviously acquired after 1949 by the government and thereafter became government estate, of which the government can decide its land use. When Ms. Cheng purchased the right of lease of this public house from the government (represented by a real-estate company), she gained the right to permanently rent this house and use it. All is fine and binding as long as the house exists. The house will exist because of Lu Xun and his legacy but Ms. Cheng was forced to negotiate a deal with the government who now wants the house back for other use.

The first day we met, we talked for two hours—covering her reminiscences from her childhood to the current situation. The conversation was later edited as a first-person narrative and printed out as a brochure for the 51 Personae event on 8 February 2017, during the 11th Shanghai Biennale. Besides the brochure, which participants of the event may take away, books and journals on the modern history of Hongkou and Lu Xun Studies were piled up on her desks and tables. Ms. Cheng had been independently carrying out historical research as a hobby since when she was young. As early as in 1990s, she shared much of her research that gathered important information on comfort women in Hongkou area with local university scholars. However, she does not agree with the one-sided patriotic narrative produced out of these historical materials as part of the nationalism argument that prevailed during these years.

She showed me a letter, she received from The Bureau of Housing Security and Management of Hongkou District, captioned: “Report on the housing expropriation compensation agreement made to Cheng Shaochan.” She has written in red, remarks on this letter such as “robbers and rogues” and “intimidating and threatening.” She underlined “the need for renovation of old houses in locations with poor infrastructure” in this letter and commented in red: “the government creates false names (to legitimise its expropriation of the houses).”

At the end of the conversation, she added that she also wondered why she had never been approached by a decent government officer but only men wearing colourful shorts and slippers, who were in fact employed by the government real-estate company to do the job. Why, after all, did she have to return her place of residence to the government for an unknown cultural purpose? Why could she as an individual not contribute to the cultural character by continuing to live there? Above all, the proposed compensation from the government was far below market value of this house and she could not afford to obtain a similar house here with the compensation.

The street of Donghengbang Road has always been home to a street market.

Photo by Chen Yun

The main gate of Jingyun Li is on Hengbang Road, a lively street which used to be a street market. Street markets have been traditionally an important form of urban life in Shanghai where people purchase daily items and fresh foods in the morning and at dusk. However, since 1990s, it has been regarded as something low and ugly, as if the city can no longer bear such indecency and shall replace them with indoor markets. With the gentrification of the city, and the demolishing of the old neighbourhoods, street markets are disappearing. After Duolun Road became Street of Cultural Celebrities, a grand gate was set up at the back door of Jingyun Li which the residents never use.

Photo by Chen Yun, 23 August 2016.

The Chinese characters of Jingyun Li were written in very humble calligraphy, as humble as the main gate when it was built in 1925: the gate opens to a lower middle-class real estate for residents who want a convenient location but who cannot afford to rent something better. Lu Xun moved here in 1927, only two years after the lane was built. It was a practice for tenants to give a big sum of money to the owner of the estate to acquire the right to lease. Under such a lease, Lu Xun moved into No. 23 Jingyun Li in October 1927. Two years later, he moved to No. 17 while Rou Shi (1902-1931), a young and enthusiastic progressive writer who was supported by Lu Xun moved into No. 23. Rou Shi was killed on 8 February 1931 along with another four left-wing writers in Shanghai, after being betrayed by someone within the Communist Party.

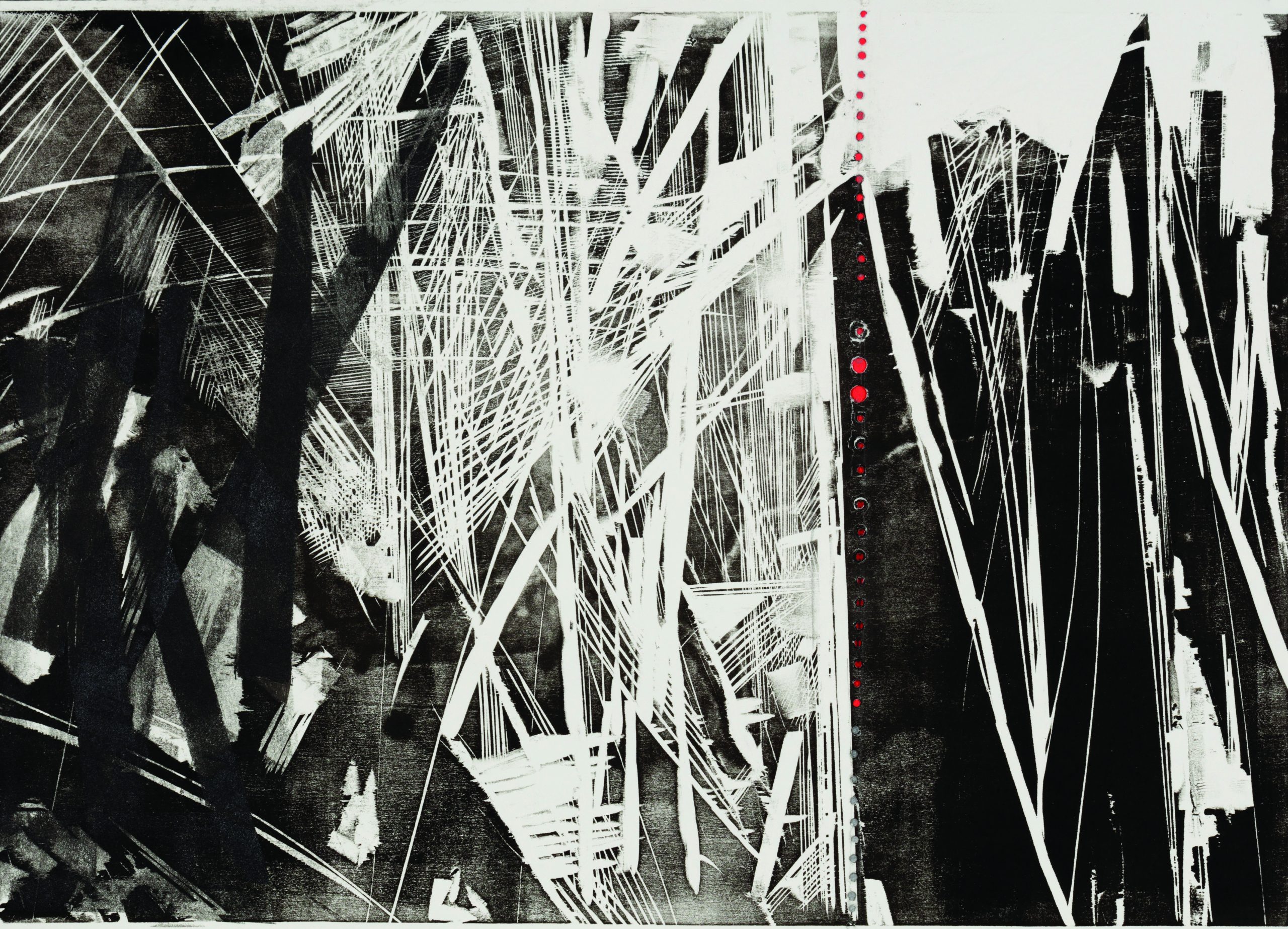

Lu Xun (1881-1936) was the first to consider foreign woodcut prints and to recognise the effective potential of using the medium to serve the needs in China, as propaganda and to promote social change. He is considered the father of the Modern Woodcut Movement of the 1930s and 1940s and a leading figure in modern Chinese literature and education. Through his lectures and writings, Lu Xun called for a new form of art that gave voice and passion to the people: the woodcut print.

A woodcut print by Li Hua (1901-1994), who was regarded by some as the best student of Lu Xun, depicts the scene of a six-day woodcut print workshop hosted by Lu Xun in a rented space not far from Jingyun Li, from 17 to 23 August, 1931.1 The teacher Uchiyama Kakechi was invited by Lu Xun as the instructor and Lu Xun himself did the translation for the younger generation of woodcut print artists. Li Hua was not among the 13 students who had participated in this workshop, which was an iconic event marking the beginning of the Chinese woodcut print movement, but he had been in constant correspondence with Lu Xun since late 1934 from whom he received his instructions on art.

Lu Xun often brought works of German artist, Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), to class and till the end of his life, promoted her works in China. In September 1931, to commemorate the death of Rou Shi and other left-wing writers, Lu Xun chose a print by Kollwitz entitled Sacrifice and published it in the first issue of magazine Beidou. This was also the first time that Kollwitz and her woodcut print works were introduced to China.

Photo by Cheng Shaochan, 7 February, 2017.

Ultimately it was Ms. Cheng who curated her own 51 Personae event. She knew what she wanted to do and when it will be done. She set the date 8 February 2017 for the event because that was exactly 86 years after Rou Shi was killed. She selected four woodcut paintings by Zhao Yannian (1924-2014) and said she wanted to know how they would look like if they are enlarged and printed at the two facades of her Shikumen house, within the lane and on the street of Hengbang Road. She knew where these images would go and we would merely facilitate and realise this project as a collective effort.

The day started early in the morning, when a group of open-call recruited participants and our friends gathered in Jingyun Li, ready with the huge plastic canvas which bore the image of the “Madman”. Cutting out the stencil and spray painting, it took almost one whole day for more than 10 people working continuously to finish. But when they were done, the final outcome resembled a book page.

(No. 31), woodcut print, 1985. Photo by Chen Yun on 7 February 2017.

To commemorate the centenary of the birth of Mr. Lu Xun, 1981.

Photo by Chen Yun on 7 February 2017.

Although he was only 10 years old when Lu Xun passed away, and had not been taught by Lu Xun directly like his own teacher Li Hua, Zhao Yannian recalls his connection with Lu Xun’s famous novel A Madman’s Dairy (1911) after the Cultural Revolution:

I read A Madman’s Diary again and again, and realised that the “Madman” is not only not “mad”, but indeed a real person who knows right from wrong.

He was “frank”, “reasonable” and “brave”.

How could the idea and composition of the painting really show the repression and resistance of the madman in the limited space of the painting? This was the first and most difficult problem I encountered. I drew a lot of sketches, arranged them and deliberated them over and over again, trying to figure out the relationship between Lu Xun’s original thoughts and my composition.

In the end, I chose to use the image and temperament of a clear, sensible, brave and confident maniac to portray him. I used a flat knife to carve, emphasised the combination of blocks and surfaces, and created a strong dynamic tone through a large contrast of black and white.

Right: Younger participants of the event sitting on the stairs and chairs listening to a neighbour (in the middle, holding a newspaper). Photo by Chen Yun, 7 February 2017.

At the evening of this long day, more people joined the gathering for the screening of a short documentary film (shot by Li Yafeng and produced by 51 Personae) on the accounts of an old gentleman Mr. Dai Fengwei (left in green of the left photo) who introduced the history of Gongyifang (무樓렌), a nearby neighbourhood also under expropriation. Mr. Dai was also a man who refused to leave, but on that evening we were told that he has been forcibly evicted by a mob of government-employed gangsters and expelled from his home where he lived since when he was five. The presence of Mr. Dai was a precursor of what woud happen to Ms. Cheng. Mr. Dai passed away one year later but his stories were documented and always remembered when we continue to observe and engage with Ms. Cheng in the days to come.

Photo by Cheng Shaochan.

Photo by Xu Ming.

One day in March 2018, when Ms. Cheng left home to visit Japan, her tenant was forcibly evicted by a mob. All their belongings were removed from the house and the door openings were sealed up with hollow bricks which were light and easy to pile up to form a ‘wall’. Strangely, after one year of rain and heat, the original spray-painted woodcut image at the south facade looked clearer than the year before. What had been washed away was the white paint that had been applied roughly to cover and censor the woodcut print image. What had been added over the ‘hidden eye’ of this image was a police notice.

By February 2019, two years after our 51 Personae event, the woodcut print image was covered by a notice board with one-sentence description of the history of Jingyun Li. A tourist/patriotic route called Lu Xun Trail was curated by the local cultural bureau in the effort to claim the significance of the left-wing literary history. Ironically, by that time, the neighbourhood which once served as both a living space and a protection for those left-wing progressive writers is almost flattened. The backstreet of Duolun Road is left in ruin and the only houses that still stood there were in Jingyun Li. Only cultural celebrities and their legacies remained but were left placeless, and out of place.

Photo by Chen Yun.

Since the house itself will not be torn down thanks to Lu Xun, one rainy winter morning in February 2019, Ms. Cheng moved back to her house with the help of friends. The house was empty. The ACs were gone and the gas, water and electricity had been cut off. Ms. Cheng went to the public service departments and asked to be reconnected with gas, water and electricity supplies. So she got them back, along with other secondhand furniture that can host her again in the house.

One day, she showed me some socks that she knitted when she was teaching a knitting workshop in Minneapolis. I then realised that she is very talented in knitting and has been interested in it since when she was six. And knitting seems to be a productive and positive way of telling her story, which I will not call a personal tragedy, but something that needs to go public exactly because it is not personal in many senses. I suggested that she knit her stories into the socks and share it with others who may be interested in stepping on the oppressive forces all around them. Or, to invite others to put on her socks and share the same stance with her. She soon produced many pairs of socks, some bearing the initiative JYL and the number 7, and some with Chinese characters of Chaiqianban (demolishing and relocation office). She joined us and presented the socks at the abC Art Book fair in Shanghai and at a special booth of 51 Personae at Power Station of Art. The socks, attractive for their unique colours, patterns and forms, were sold for 15-20 RMB and made popular purchases.

Photo by Cheng Shaochan

Photo by Mira Ying

Inspired by Ms. Cheng’s socks, our artist friend, Yingchuan, designed a silk scarf based on a fable that she had written called Max and animals dance in the belly of the big snake; it teaches how to negotiate with evil forces even when one is swallowed by them. The work is called A Letter from Jingyun Li. This picture (above) shows Ms. Cheng under this flag-like silk scarf on the National Day fair at Power Station of Art.

Photo by Emma Mou

Just one month after that, Ms. Cheng found herself evicted again. All her secondhand furniture was gone and moreover, the staircase between the first and second floor was demolished. Ms. Cheng, daughter of revolutionary parents who were buried in the same martyrs’ cemetery as Rou Shi, decided that she will stay in the house on the second floor. She received her supplies by the rope-and-basket system, and by that time, many people including Emma, who had spent a couple of months with her on the third floor (and whose belongings were also removed along with Ms. Cheng’s belongings) gave her support of various kinds. Young people who learnt about her story online came to the house to spend nights with her, in fear that another forced eviction might happen for a third time.

And the forced eviction did happen once again in one night in December 2019. When that happened, she decided to live in the local police station, where she had taken up temporary residence during the last eviction. People continued to visit her at the police station and to give her supplies and support. During the day, she would sit at the very last row of the reception hall, while at night, she will sleep in a smaller separate room with AC. When everyone thought that she would be living in the police station for a few more days till the government sent a representative to negotiate with her, she was unexpectedly brought away by the police to be sent to a custody-asylum in north Hongkou, on Shuidian Road. But since her registration (hukou) was in Shanghai, she did not qualify to be admitted there. Consequently, she was sent back to the police station; however this time, she decided to sleep in front of the Sub-district Office of North Sichuan Road) just adjacent to the police station. The following morning, she was brought by force into the Sub-district Office where she lost connection with all the relatives and friends for 11 days before she was released.

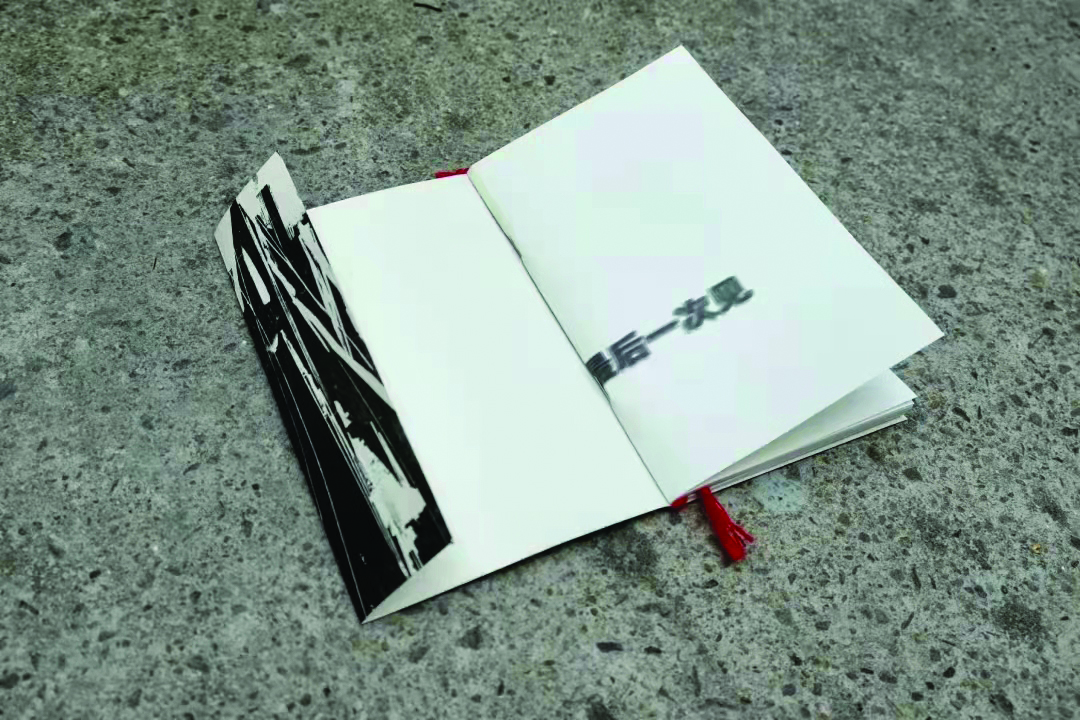

Image courtesy the artist.

During these 11 days, Emma and I began to invite about 40 people to contribute to a writing commission under the title of The Last Time I Saw. We invited them to describe the moment of their last meeting or encounter with Ms. Cheng, either it be two years ago, or two days ago. We selected and edited 26 pieces and finally compiled them into a little book. We arranged them (either poems or essays) in a timeline from earliest to the most recent. The little book also became a witness/expression of an ‘emergency’ moment that went all the way back to two years prior to the moment when Ms. Cheng went missing. The contributors did not necessarily know one another but they share one commonality which is that they knew Ms. Cheng and shared her concern regarding her problem. They were all witnesses of an emergency which they felt did not happen only to Ms. Cheng as the one who was evicted and refused to leave her house, but an emergency that mattered to everyone in our own daily life experience. Memory, if not captured immediately, may go blurry and may never again be more accurately told in a documentary format.

The cover of this book was gifted to us by an anonymous woodcut print researcher and artist. She produced this piece earlier that year and found this work appropriate to serve as the cover of the book. Wild Grass was also the title of a famous prose collection by Lu Xun. The book was ‘published’ a week before Wuhan Lockdown in January 2020. The contributing authors were the first readers of this book, and through this, they became aware of a bigger picture of Jingyun Li event.

Photo by Mira Ying

Since 2018, 51 Personae has been using “Jingyun Li No. 7” as the address of the project, printed on the copyright page of each 51 Personae work. Ms. Cheng never returned to Shanghai since Covid-19 broke out in 2021.

Emergencies, like most human phenomena, repeat themselves. In the case of Jingyun Li, 51 Personae had attempted to tease out and engage with what constitutes a long-term emergency, an emergency that may not look obvious as an emergency to most people most of the time, but is.

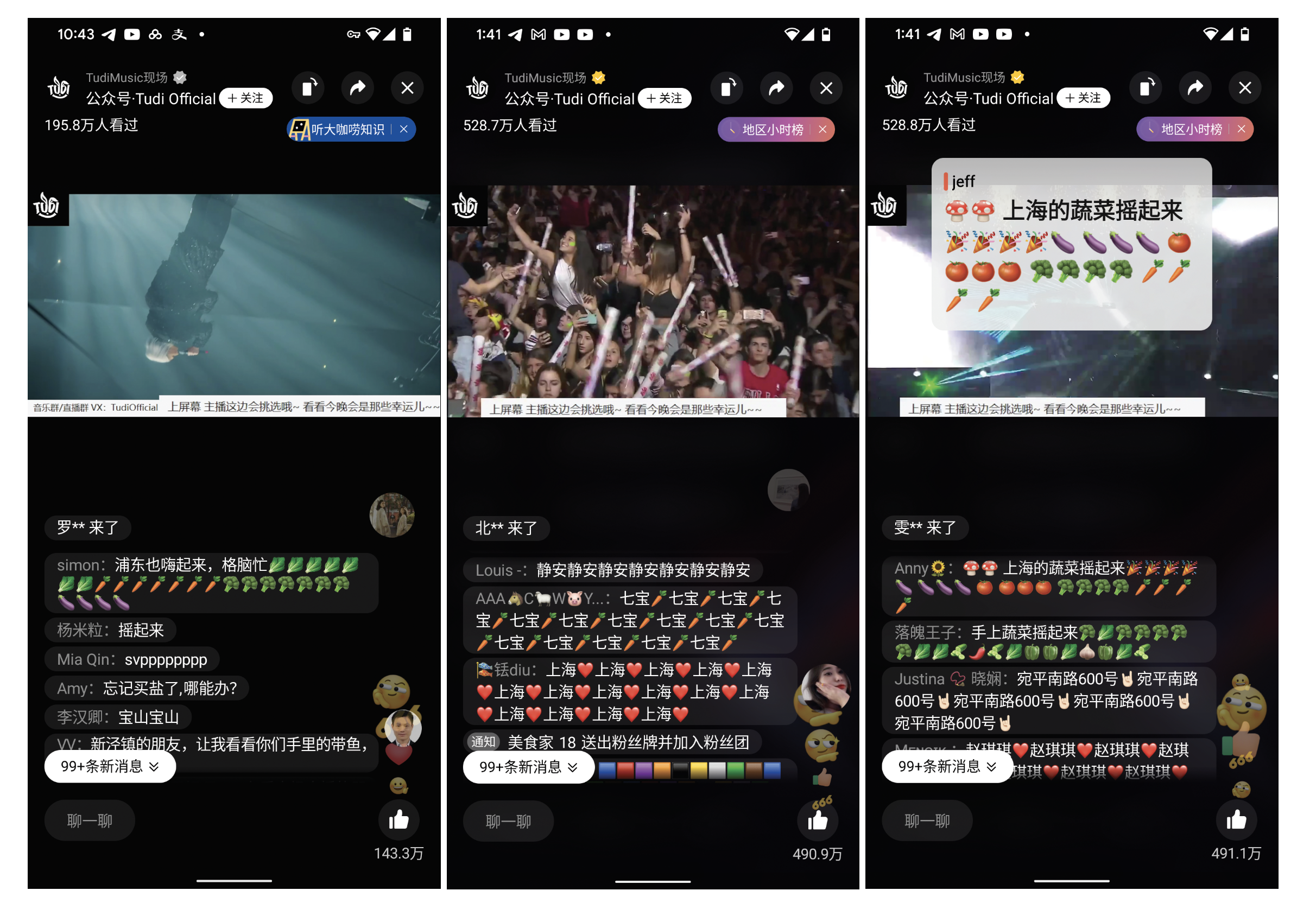

Screenshots by Chen Yun.

An online Spring Festival Gala attracted more than 5 million participants at the night of 31 March 2022. Starting from midnight of 1 April, the West part of Shanghai (Puxi) went officially into lockdown indefinitely. Before that, the East part of Shanghai (Pudong) had been in lockdown for two weeks. Under an ominous cloud, people had rushed to the markets to get whatever foods available at whatever price.

This online Gala was a playback of Ultra Music Festival 2022 at Bayfront Park (March 25-27) in Miami on an electric music wechat video-channel called Tudi Music. Tudi Music did not expect a viewership of a 5-million strong audience, mostly from Shanghai, who participated with passion and spirits no lower than those in Miami, shaking carrots, cabbages and onions in your hands and calling out the names of the neighbourhoods where they are from. This bottom-up celebration of the uncertainty of the Shanghai 2022 Spring Covid lockdown can be seen as a collective activation of an impending state of emergency.

The lockdown following that midnight lasted for an entire two months, when people were not allowed to leave their apartments or their neighbourhoods. Streets were emptied with only vehicles for emergencies and necessities. The city went vacant and the most only obvious sounds heard were from the sirens of ambulances. The cost of this silent spring in Shanghai is still yet to be documented, recognised, and understood—it needs a long-term effort from artists and cultural workers. I have flashbacks of the scene of Ms. Cheng collecting food with a rope-and- basket from the window of her second floor as I write this photo essay. If that was a moment when a personal experience has the power to infiltrate a small part of the public, then likewise we—drawing from our own daily lives—as witnesses as a city of 25 million to this spring of 2022, have the power to open our eyes and hearts to observe the sufferings of others and think about the mechanism behind the ‘emergencies’.

Image courtesy the artist.

Essays

Rising From The Flow

Prelude

Today in Tehran, the traces of the past and the thirst for running towards the future are intertwined in such a way that we have lost the ability to speak about the coordinates of our consciousness. By ‘speaking’, I mean the retelling of the story that the city expresses through architecture. To have a stuttering tongue does not point to our muteness; exactly at the point that we fall silent, the city starts to speak, breaking the silence in a language of fragmented and incongruous alphabets that constructs its words with letters from a multitude of tongues.

The Alborz mountain range and its majestic peak, Mount Damavand, or in the words of the poet, Malek osh-Sho’arā Bahār (1886-1952) in his poem, The Chained White Beast, Damavandiyeh (The Dome of the Universe) is the city’s only true compass.1 The experience of life in the city of Tehran highlights, evermore, the special place that Damavand has in Persian mythology. It is in reference to it that we can still locate our place, despite being lost in this speed. In the background of the city’s image, and amidst its bizarre transformations and constant metamorphoses, Mount Damavand reminds us powerfully of where we stand whilst the foreground image’s exponential growth contends to erase the image of that sleeping volcano.

The poet Bahār, writes, in the same poem:

You are the lethargic heart of the earth

inflamed from pain

covered with camphor balm

to calm bruise and pain

Explode, thou heart of the times

and do not choose to hide your inner fire

“Explode, thou heart of the times” is an exhortation for the sleeping volcano’s eruption: an intervention that the poet asks of Damavand in this urgent situation, exactly one hundred years ago. Bahār asks Damavand to impregnate the clouds and bring down the rains, while in another line he begs it to burn everything down with the fire of its rage.

And today, much like a century ago, the world that surrounds Damavand is still trapped in a state of emergency, and it is this enormous, live mountain that ultimately determines the spiritual geography of its location: the need to refer to its power and beauty, more undeniable than ever, rises before our eyes every morning before the avalanche of smoke and dust makes it disappear.

An emergency is a situation that invites the alert mind to intervene. Like a healthy and conscious mind that belongs to the fragmented, torn and tired body of this city, Damavand, alive and aware, understands all that is going on in the city’s body: how it denies the emergency at hand with an obsessive fervor, pushing reality to the margins in favour of a theatrical charade of order that is in fact founded on anarchy.

I invite you towards the coming lines that lay ahead, not from the point of view of a writer, but that of an installation artist who builds spaces with words. I will let you wander amongst the things that I find myself wandering amidst: in the space of in-betweens, somewhere between reality and truth, between being the narrator and the narrative, between being the object and the subject, between seeing and being seen, between imagination and fact, between our truth and post-truth.

Interlude

I burned it,

since building is in burning.

I destroyed it since construction is in destruction.

Shams-i Tabrīzī2

Site/Body

Crime scene detectives believe that the body of the murdered speaks to us silently, recounting the entire story of the murder. I believe that places, much like the corpses of murdered bodies, can tell us about the coordinates of a culture, its political and social conditions—in short, all that happens in that place. My aim in writing this piece is to translate the story that this architecture is telling and to place it in the context of this essay. I intend to rebuild and move this body, which I see as the body of society, in order for the reader to access it and to observe and decode it. The space that I recreate here, is indeed a synthesis of my simultaneous observations and interpretations: a “second edition” coupled with a narrative and at times with emphasis on the parts that can convey important information about this body to the reader, much like the spotlight that shines on the main character on a theatre set.

Observation/Encounter

‘Observation’ is the starting point of every piece that I make; and then ‘writing’ which fills the distance between ‘seeing’ and ‘revealing’ of things. Words make it possible for me to redefine phenomena in a relatively far distance from ‘what the other sees’.

Writing, in my work, is the first step in defamiliarising of phenomena: the first step on the difficult path of revealing ‘what I see.’ In a way one can say that what you are reading is not a reportage, but the result of an encounter. In my view, this work is a non-physical installation in a different context. My approach in the organising and processing of this text and its illustrations before you is the same as my approach in creating installations in the white cube of a gallery or any other space.

Location/Situation

In the city, objects pile up and then sediment, and their dregs flow to the margins. I write: ‘dregs,’ I read: ‘essence’; much like the people whom in the present world resemble mere numbers. All the materials for the construction of a space are available here in the outskirts of the city. The city is constantly dredging, like the flow of a river that moves the garbage to its banks and continues to flow freely on its bed. But to understand what is happening to the river one has to look at its banks, and to understand the sea one has to step on its shores.

The abandoned brick kilns in the eastern margins of Tehran were home to a small community of people who have had to move to the outskirts of Tehran to work at these factories. Today, after 20 years most of the kilns have shut down and the better part of the families work in other factories or make ends meet by recycling garbage or construction waste. A hosseiniyeh is built in this neighbourhood voluntarily by the members of the community. Hosseiniyeh is a building type for the performance of religious ceremonies and is supposed to be a place for tavasol, which means to appeal and is derived from the word vasileh which means instrument. The Prayer of Tavasol is one of the most important group ceremonies that happens in a hosseiniyeh. It is a plea to the instruments of closeness to god. Here, instrument suggests something more than a thing or a tool, it is a cause. In this setting, the hosseiniyeh is the meeting place and appeal is the intention. The difference between this hosseiniyeh and any other architecture is in that it conflates the image and the meaning of its geography.

Territory/Sanctuary

The most common building material in this neighbourhood and in most other slum dwellings is construction waste. One can see a slew of these heterogenous leftovers used as building parts in slums; for example, doors discovered as found objects amidst construction waste or purchased from demolition workers.