VOLUME

ISSUE 08

Erase

Three perspectives anchor the will to erase.

These three perspectives form the basis on which one can help ascertain the current station of contemporary society. Looking through the prism of art, politics, power, technology, spirit, and reality-visual culture and ideas, can the notion to easily erase or delete be seen to relativise our understanding of truths today? Moreover, the will to delete is an integral part of digital socialisation today as such it affords the emergence of new cultural myths and forms. How do these manifest in contemporary art and visual culture?

ISSUE 08

2019

Erase

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Essays

Conversation

Exhibition

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Erase

Essays

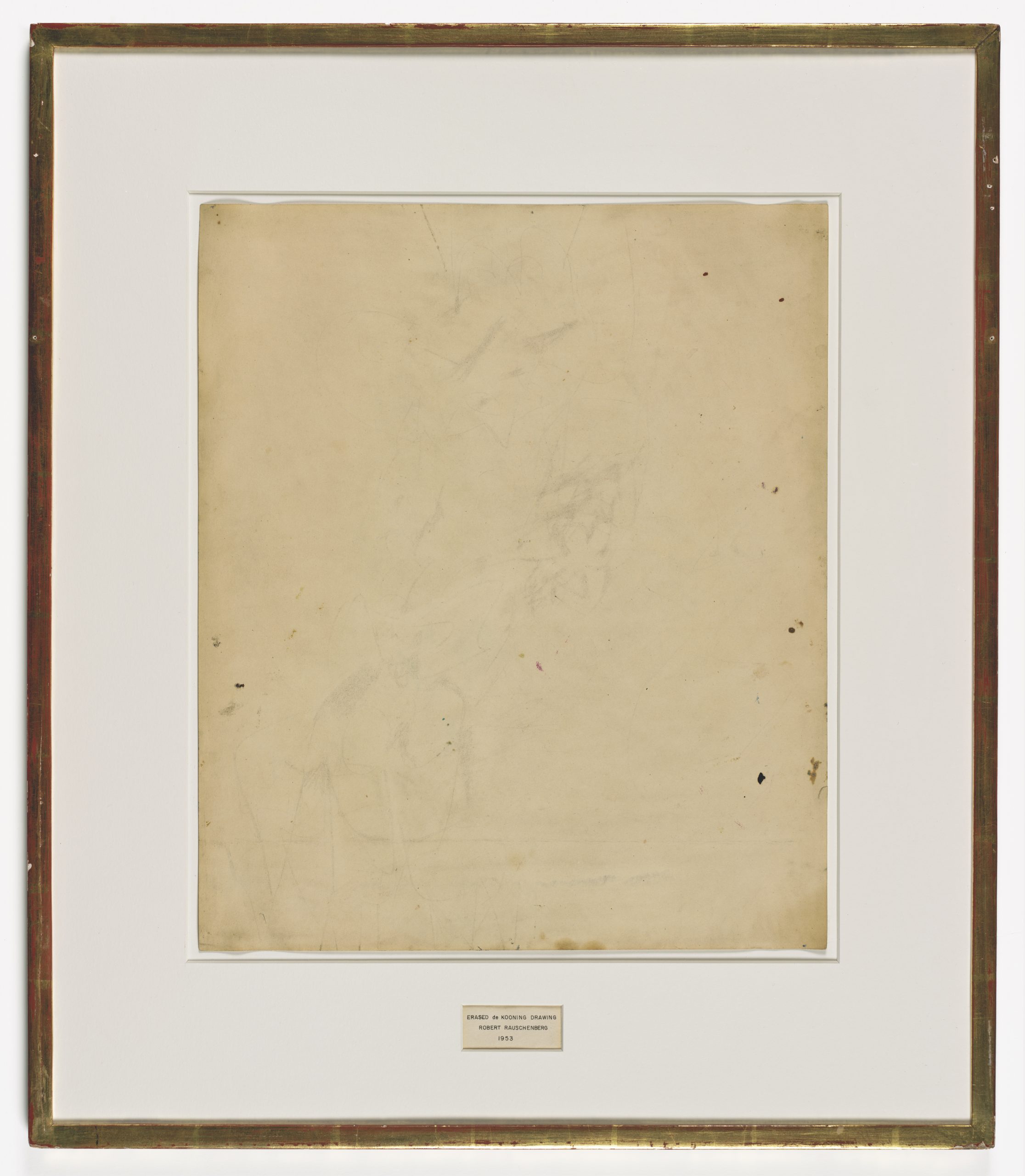

ERASURES: Being, Seen

The Fact Remains

Conversation

Exhibition

Disintegration Loops An Exhibition in Print

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy Editor

Jean Wong

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Editorial Board

Professor Patrick Flores, University of the Philippines

Dr. Peter Hill, Artist and Adjunct Professor, RMIT University, Melbourne

Professor Janis Jeffries, Goldsmiths, University of London

Dr. Charles Merewether, Art Historian, Independent Researcher, Curator and Scholar

Manager

Sureni Salgadoe

Contributors

Jorella Andrews

Dejan Grba

Charles Merewether

Nils Plath

Sam I-shan

Clare Veal

Ian Woo

Andrea Luka Zimmerman

The Editors and Editorial Board thank all reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments and feedback to the contributors.

Introduction

Introduction: Erase

The 2019 issue is Erase.

The concept of ‘erase’ has informed much of 20th-century art, philosophy and cultures through either a palimpsestic re-writing/re-reading of issues, confrontation through the ideology of war or through forgetting. These practices speak directly to identity formation, cultural/self-representation and the manner in which the future is factualised.

But humanity is driven by a constant need to erase and this is foregrounded by three perspectives.

First, to erase is to existentially oppose memory or the memorialisation of that which is/was present. History’s pre-occupation is not so much with what is/was present but that which is absent in the past. In these pre-occupied notions of archiving, there is a fundamental annihilation1 of any form of representation of humans and beings of their rich and diverse manifestations by not acknowledging their presences: Their absences promote stereotypes. The last century provided and continues with thick scholarship around identities, race, genders, geographies, languages and sexualities. These inform and direct contemporary culture, art and education.

Secondly, in the current era, where the digital reigns supreme, one is memorialised and traced through Google histories or IP addresses, enabling market to demographic profiling for purposes of framing identities, publics and communities. This has led to market and political forces to shape, manage and control people’s decision-making. With this, the right of an individual to erase/mask through automated identity control (facial, fingerprint recognition) and encryption technologies such as VPN has become pronounced and an integral part of human digital socialisation. That is, the right to erase/delete not memorialise/archive is at the heart of legal debates around data protection today.2

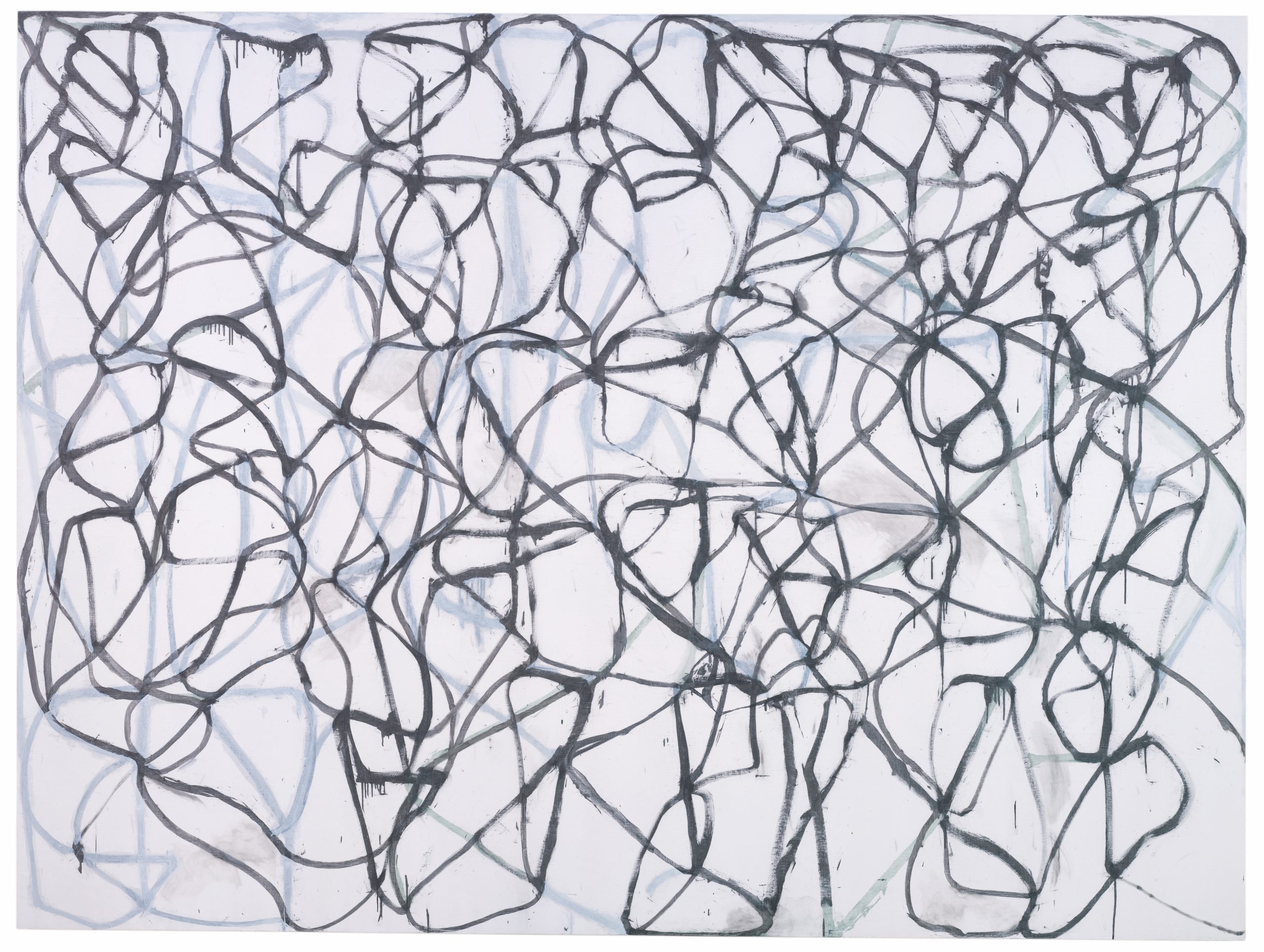

Thirdly, in visual art, to erase is a method of consistently bringing to light a new perspective or dimension. In art, distancing oneself from the need to erase (to forget) is pertinent in unleashing ways of imagining the world and bringing to the forefront ideas deeply buried in the human conscience.

These perspectives form the basis of the current ISSUE. Looking through the prism of art, politics, power, philosophy, and reality-visual culture and ideas, these curated essays, interview and exhibition, consider the manner in which the notion to easily erase or delete can be seen to relativise our understanding of contemporary society. Moreover, they provide an avenue to the reader to consider the emergence of new cultural myths and forms and how these may manifest in contemporary art and visual culture.

Footnotes

1 Gerbner and Gross

2 Mayer- Schönberger

References

Gerbner, George and Gross, Larry. “Living with Television: The Violence Profile.” Journal of Communication, Vol 26, No. 2, 1976, pp. 172-199.

Mayer-Schönberger, Viktor. Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Essays

Introduction

This text addresses the questions of erasure, deletion and disappearance in new media art from the aspect of preserving, archiving and representing the emblematic line of generative art practices whose poetic qualities make them museologically problematic within the technological and institutional context of the early 21st century. Contemporary generative art often combines procedural (algorithmic) thinking with bricolage methodology and relies on the infrastructures such as the Internet or the AI systems which are becoming ubiquitous and essential but remain largely elusive, exclusive, opaque and misunderstood.

We explore this interrelatedness by discussing some of the exemplar generative art projects which transcend the expressive and aesthetic limits of code-based art but prove to be difficult to preserve and are relatively underrepresented within the art world. With respect to the existing literature in the area, we show that the material fragility, the cognitive values and the educational potentials of generative art practices all stem from their conceptual, methodological and technical sophistication, pointing to the uncertain cultural status of generative art and to some general yet ambivalent issues of memory, re(cognition) and preservation.

Context

Erasure, deletion and disappearance in new media art manifest on two planes: as themes of the artworks and through the material and cultural instability of the artworks. Among the notable examples of new media artworks which directly thematise and apply the concept of erasure is Martin Arnold’s project Deanimated (2002). In this deconstruction of cinematic conventions, the artist gradually removed both visual and sonic representations of the actors in Joseph H. Lewis’ B-thriller The Invisible Ghost (1941), and consistently retouched the image and sound so that the final minutes of the film show only the empty interior/exteriors accompanied by the crackling of the soundtrack.1 Erasure and removal are frequently used in critical game modifications, for example in the works of Jodi (the collective Joan Heemskerk & Dirk Paesmans)2 and Cory Arcangel3 or in post-conceptual artworks such as John Boyle-Singfield’s Erased Cory Arcangel Website (2013).4

Accumulation of the clients’ personal data, behavioural tracking, prediction and manipulation of decision-making are the essential strategies of large-scale systems such as industry, marketing, advertising, media, banks or insurance companies, which all rely on frequent information exchange and processing. Computationally enhanced and virally exploiting the evolved human need for socialisation and communication5 on the social networks, the new iterations of these old corporate strategies refresh our appreciation of privacy and need for anonymity in a constant arms-race between the systems of control and the tools for individual advantage. This social tension within digital culture was exemplified in the early 1990s by net artists such as Heath Bunting6 and Vuk Ćosić,7 who escaped and denied the formal abundance promised by the early World Wide Web as the most popular and commercially most attractive Internet protocol. Similar approaches to reduction, avoidance and abandonment have been central in many later tactical media artworks such as Institute for Applied Autonomy’s iSee (2001),8 anonymous artists’ Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc. (2014)9 or Zach Blas’ Facial Weaponization Suite (2011-2014).10

New media artists also address the broader topics of transience and perishability of the (digital) cultural artefacts, often by applying generative algorithms to the various contents, for example in the work of Jason Salavon,11 in Ben Fry’s HSV Space Arrangement (1998),12 Rhyland Warthon’s Palette Reduction series (2009),13 Chin-En Keith-Soo’s Hueue (2017)14 and many others.

Generative Art

The conceptions of generative art in contemporary discourse differ by inclusiveness.15 In this text, we perceive generative art broadly, as a heterogeneous realm of artistic approaches based upon combining the predefined elements with different factors of unpredictability in conceptualising, producing and presenting the artwork, thus formalising the uncontrollability of the creative process and underlining the contextual nature of art.16 Like all other human endeavours, the arts always emerge from an interplay between control and accident, and exist in a probabilistic universe so, in that sense, all the arts are generative. However, the awareness of the impossibility to absolutely control the creative process, its outcomes, perception, reception, interpretation and further use is often not the artists’ principal motivation, but it becomes central in generative art. Generative art appreciates the artwork as a dynamic catalysing event or process, inspired by curiosity and playfulness, susceptible to chance and open for change.17

Contemporary generative art has emerged from the Modernist exploration of the nature of creativity, of the material, semantic and contextual identity of the artwork, influenced by information theory, systems theory, cybernetics and semiotics throughout 20th century.18 The use of instructions and language in minimalism and in conceptual art introduced the algorithm and procedure as formal elements but also as participatory factors, as seen in works by Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner and George Brecht. It emphasised that the operation of an algorithm, as a structured set of rules and methods, may be well comprehended but its outcomes can evade prediction. The cognitive tension between the apparent banality of pre-planned systems and their surprising outcomes became one of the major poetic elements in Steve Reich’s opus in the 1960s, with astonishing effects of phase shifting, iteration, repetition and accumulation of musical figures, in processual artworks such as Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube (1963), and in some land art projects such as Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977).19

Generative techniques figure prominently in new media art. Aware of its dubious nature and diverse meanings, we use the term ‘new media art’ to denote a rich repertoire of practices based upon the innovative, experimental, direct or indirect application and exploration of emerging technologies often in correlation with scientific research, which strategically redefine the notions of traditional and new media, and challenge the distinctions between artistic process, experience and product.

Generative new media art expanded in the early 21st century with the development of hardware and software systems, coding environments and computational techniques for efficient manipulation, transformation and interaction of various types of data. Diversifying conceptually beyond purely computation-based methodologies—which drew considerable and well-deserved criticism but are still widely recognised as ‘the’ generative art—the production of contemporary generative art unfolds into a broad spectrum of creative endeavours with different poetics and incentives which frequently include bricolage.20

Bricolage

Bricolage is an approach that combines affinity and skills for working with the tools and materials available from the immediate surroundings. Reflecting the necessity-driven pragmatism of Italian neorealist filmmakers in the 1940s and 1950s, bricolage became popular with the Arte Povera movement during the 1960s as a critical reaction to the commodification of the arts.21 Since then, it has been adopted, adapted and explored in various disciplines including philosophy (epistemology), anthropology, sociology, business, literature and architecture, and it has become almost transparent in a wide range of artistic domains.

Introducing the concept of bricolage in The Savage Mind (1962), Claude Lévi-Strauss noted that while an engineer always tries to make her way beyond the constraints imposed by a particular state of civilisation, a bricoleur—by inclination or necessity—remains within them.22 Bricoleur accumulates and modifies her handy means (operators) without subjecting them to a predefined objective but the objective gets shaped by the interactions among operators.23 Bricolage is therefore central in generative art in which the projects are conceptualised and developed through playful but not necessarily preordained experimentation with ideas, tools and techniques. Constantly pushing the envelope of methodology, production techniques and presentation environments, generative new media artworks tend to be unstable and their full functionality difficult to maintain in the longer perspective, so they face the dangers of cultural survival.

Keep/Share 101

The first wave of systematic curation, archiving, preserving and representing new media and generative art has started in the second half of the 1990s with Christiane Paul, Paola Antonelli, Charlie Gere, Wolf Lieser and Oliver Grau among its most notable proponents working with the institutions such as ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Museum of Modern Art in New York and online initiatives such as DAM (Digital Art Museum). They had been predominantly dealing with the technical challenges of the software/hardware dynamics of the 20th century24 and with the conceptual challenges of new media art being perceived as somehow less object-based and more participatory, processual, temporal and transitory than the traditional fine arts.25 This required new understanding of the museum as a cultural institution, establishing new curatorial models and collaboration with the artists, new representational strategies and audience engagement.26

These efforts had been confronting many technical obstacles caused by the inherent technological impermanency and obsolescence, for example with esoteric analog computers, mainframes, plotters or film printers that computer artists used in the 1960s and 1970s. Although a number of their works had been lost for technical reasons, many were preserved as program code which can be emulated in modern programming environments, rendered and materialised with modern hardware. Some can be formally interpreted and reconstructed even without the original code by reverse-engineering the originally produced imagery, for example in projects such as The ReCode Project initiated in 2012 by Matthew Epler;27 Digital Art Gallery (2014) by Joachim Wedekind;28 and Pattern Recognition (2017) by Martin Zeilinger.29

Complexity

Intentionally or spontaneously, contemporary generative artists tend to work in diverse bricolage style, building their projects upon multi-layered interconnections between programming languages, libraries, APIs, software protocols, platforms and services that run on networked hardware with significantly higher complexity and pace of change. In everyday life, we consider these technical layers ubiquitous, often invisible and guaranteed components of cultural infrastructure, but they are unstable and unreliable because they evolve according to the unpredictable changes in economics, technology and politics. Common technical functionality is primarily aimed at satisfying the relatively narrow windows of current procedural requirements and commercial demands, with reduced margins for backward or forward compatibility.30 Generative artists find it difficult to keep their own projects running when their hardware/software environments change significantly enough, usually in a time-span of several months and few years. One institutional response to this challenge reflects the solutions of the first wave of new media art museology: keeping the original hardware systems operational, continuously maintaining and updating the software components, and developing emulators for running the archived artworks on modern hardware.

However, many contemporary generative artworks are also time-based, continuous, interactive and require a critical number of network transactions during production and/or exhibition. Some projects have been created with the specific intention to engage the social and political consequences of ephemerality, and to address the fragility of information technologies by emphasising their transitory character. Performative complexity is essential for their poetic identity and experience, so it is difficult to recreate or preserve these works without proper functionality of all their external interdependent layers.

Some notable generative art projects have been anticipated with these issues of technical complexity in mind, so they had been initiated as live processes or events but finalised and exhibited as the more permanent records or documentations which represent their poetic identity.

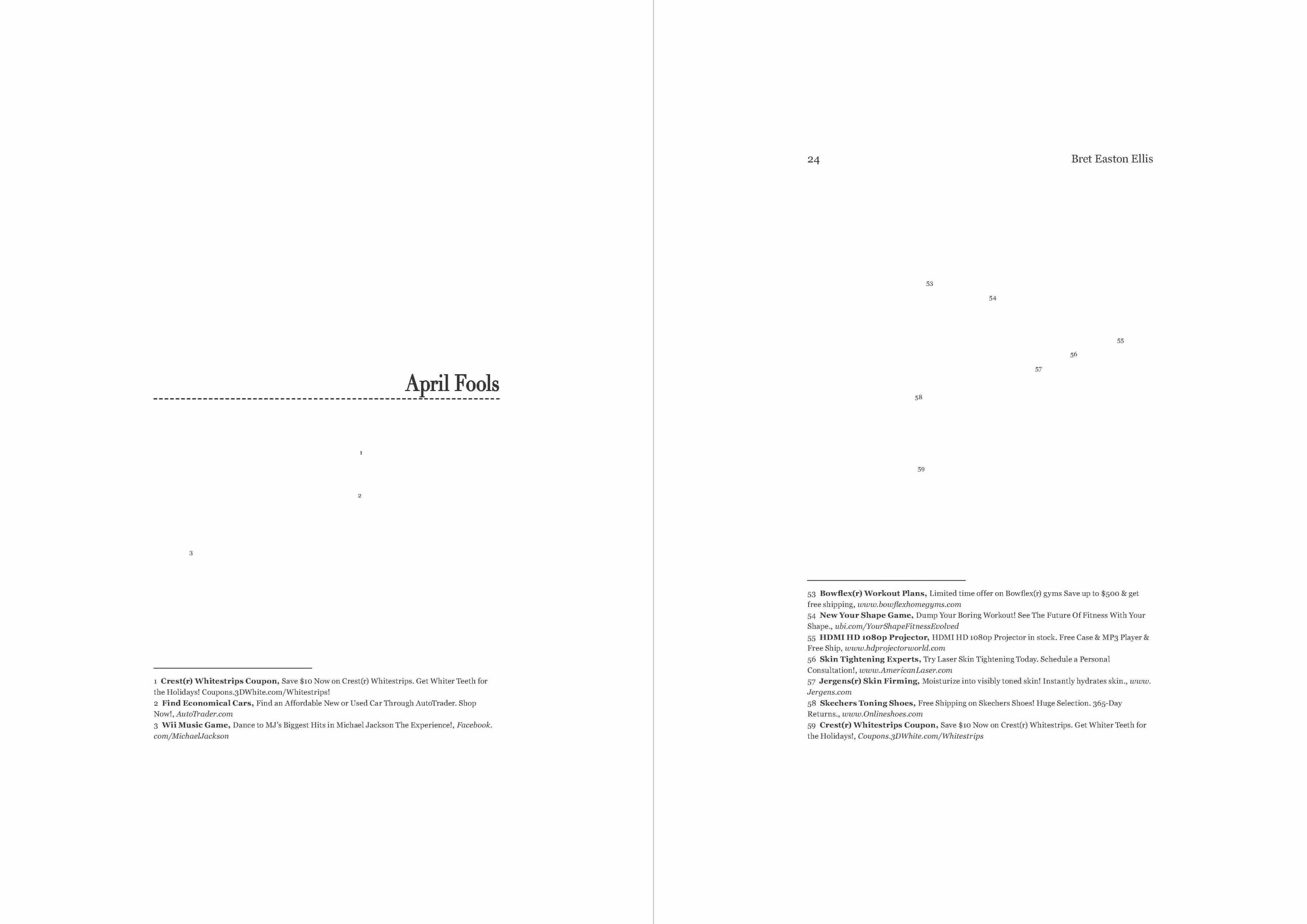

Figure 1. Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff, American Psycho (detail), 2010

Photo: The artists

For example, the online profit-oriented recognition of linguistic and behavioural patterns was deftly subverted by Mimi Cabell and Jason Huff in American Psycho (2012). The artists mutually Gmailed all the pages of Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho (1991), one page per email, and correspondingly annotated the original text with the Google ads generated for each email. They erased the original email/novel text, leaving only the chapter titles and the ads as footnotes. The initial generative phase of emailing could have been manual or programmed but the outcome of this project is a printed and bound book (Figure 1). American Psycho (2012) recursively employs the early 21st century marketing strategies based upon data-mining to process the narrative about the paroxysms of business culture in the early 21st century.31

In Google Will Eat Itself (GWEI) (2005) by Übermorgen, Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico, the initial production phase required automatic procedures, and was temporarily featured as a live online event, but the project has since been exhibited in documentary form. The artists hijacked Google’s AdSense initiative by designing software bots to click on banner ads placed on a network of hidden websites. Another set of bots channeled the generated revenue to buy Google’s shares and distribute them publicly via GTTP Ltd., which would eventually turn Google into a public company.32 GWEI was executed as a proof of concept with a purpose to address the control of information and the banality of online advertising mechanisms by outsmarting their own operational logic, rather than to actually buy out all Google stocks. After 1,556,361 AdSense clicks that generated USD$405,413.19 and bought 819 Google Shares, the bots were disengaged and since then the project has been properly represented by documentation detailing all phases, effects and consequences (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Übermorgen, Paolo Cirio and

Alessandro Ludovico, Google Will Eat Itself, 2005

Installation view of Hacking Monopolism Trilogy at China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China

Photo: Paolo Cirio

Figure 3. Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico, Face to Facebook, 2010

Installation view of Artists as Catalysts exhibition in Azkuna Zentroa, Spain

Photo: Paolo Cirio

In Face to Facebook (2010)—the final project in the Hacking Monopolism Trilogy that began with GWEI and Amazon Noir (2006)—Cirio and Ludovico created a bot which harvested one million Facebook profiles, filtered out 250,000 profile photos, tagged them by the facial expressions (relaxed, egocentric, smug, pleasant, etc.) and posted them as profiles on a fictitious dating website called Lovely Faces at http://www.lovely-faces.com.33 Lovely Faces had been fully accessible and searchable for five days, during which the artists received several letters from Facebook’s lawyers, eleven lawsuit warnings, and five death threats.34 The project has since been presented as a multimedia documentary installation (Figure 3).

Figure 4. !Mediengruppe Bitnik, Random Darknet Shopper, 2014-2016

Installation view in Kunsthalle St. Gallen, Switzerland

Photo: Gunnar Meier/ Kunsthalle Sankt Gallen

Figure 5. !Mediengruppe Bitnik, Random Darknet Shopper, 2014-2016

Installation view in Kunsthalle St. Gallen, Switzerland

Photo: Florian Bachmann

!Mediengruppe Bitnik’s Random Darknet Shopper (2014-2016) was a live generative project that pragmatically exploited web anonymity tools such as Tor (Figures 4 and 5). It was an online shopping bot which roamed the dark web marketplaces such as Agora or Alpha Bay where it randomly purchased items within a weekly budget of $100 in Bitcoins, and had the goods mailed directly to the exhibition space where they were displayed, with a screen device monitoring the bot’s shopping activities.35 The gallery presentation of Random Darknet Shopper now features a collection of purchased goods with a display record of the bot’s shopping activities and its various consequences.

Many generative art projects, on the other hand, feature continuous real-time transactions between intelligent networked agents. They can be preserved as documentation, and can be simulated by sampling the pre-recorded events, transactions and triggers from a database. But a simulation cannot fully rebuild their emotional space which requires our real-time involvement with the remote agents’ actions and their consequences. Our empathy in this seemingly ambivalent participation is facilitated by the contextual insights emerging live from the abstraction layer of technology.

Figure 6. Matthieu Cherubini, Afghan War Diary, 2010

Screenshot

Figure 7. Nicolas Maigret and Brendan Howell, The Pirate Cinema, 2012-2014

Installation view

For example, in Matthieu Cherubini’s installation Afghan War Diary (2010) the artist’s website connects to an online server for Counter-Strike war game and retrieves frags (events when one player kills another) in real-time (Figure 6). These frags trigger a chronological search in the Wikileaks database containing over 75,000 secret US military incident reports on the war in Afghanistan. Based on the retrieved data, the website shows the geolocation of the incidents on a virtual globe in three-channel arrangement.36

With The Pirate Cinema (2012-2014), Nicolas Maigret and Brendan Howell merge the sampling of film and TV with the world of live peer-to-peer exchange (Figure 7). Their installation monitors the 100 most-downloaded torrents on a popular tracker website, intercepts the video and audio snippets currently being served, plays them on the multichannel screen set with the information on their origin and destination, then discards them and repeats the process with the next stream in the queue.37

In Take a Bullet for This City (2014), Luke DuBois emphasised the contextual factors of the allusiveness of selective quantification regarding gun violence in the US. The 911 calls reporting a ‘discharging firearm’ in New Orleans are registered in real-time by a computer-driven mechanism that pulls the trigger of a real, blank-firing handgun installed in the gallery, ejects and accumulates the spent cartridges into a vitrine.38

Entanglement

Generative artworks that feature multi-directional, real-time and continuous interaction between intelligent actors cannot be adequately represented through a simulation.

Figure 8. Matt Richardson, Descriptive Camera, 2012

Photo: Matt Richardson

Figure 9. Jonas Eltes, Lost in Computation, 2017

Installation view in FABRICA Research Centre, Treviso, January 2018

Photo: Jonas Eltes/FABRICA

For example, in Matt Richardson’s Descriptive Camera (2012), a photographed image generates narrative interpretation by the remote human agent (Figure 8). When we point the Descriptive Camera at a subject and press the shutter button, the device does not display the image but sends it simultaneously to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk where human ‘workers’ write down its description, and the device prints it out.39 While modern digital cameras capture various contextual metadata of the photographs, the Descriptive Camera only delivers the metadata ‘about’ the photographed content, and deliberately requires human intellectual labour for image processing instead of the artificial intelligence like, for example, Ross Goodwin’s application word.camera (2015) which translates photographs into narratives using AI.40

Reflecting Ken Feingold’s earlier generative works with AI speech synthesis and recognition, in Jonas Eltes’ installation Lost in Computation (2017) all agents are non-human. It continuously generates a real-time conversation between a Swedish-speaking and an Italian-speaking chatbot connected through Google Translate (Figure 9). It simultaneously highlights the absurdity of machine cognition and provides the evidence of the current level of accuracy and flexibility that language modelling algorithms have achieved.41

One of the key poetic factors in these artworks is our awareness of the uncanny emerging from heterogenous, dislocated, concurrent and actual processes, including the creative dynamics of the AI/ML systems. Hypothetically, this kind of generative artworks could be emulated by sophisticated networks running AI/ML software trained to imitate the behaviour of human and machine agents. From the current perspective this would be unreasonably expensive or technically impossible but could be attainable in the future with sufficiently detailed specifications of each artwork’s structure and functionality.

Originating since the early 2000s, these conceptually sophisticated and technically advanced but museologically unstable generative art practices precede and, somewhat ironically, precondition the post-digital art.42 Post-digital artists take digital infrastructure pragmatically (as a common utility), and use digital technologies to thematise the phenomenology of contemporary culture but mainly produce their works in conventional materials and non-interactive media. Their aestheticisations of the proliferation of digital artefacts and effects resemble the cool, disillusioned and detached observation which became popular with the artists in the mid-1970s New York City,43 and diversified in postmodern art during the 1980s. Being easier to exhibit, preserve, own and sell, they also conform more smoothly to the conservatism of the mainstream art world.44

Universal(instabil)ity

But the conservational risks and cultural uncertainty haunting contemporary generative art are not exceptional. They arise from the asymmetry between the artists’ inventiveness, anticipations and technical resources, and are as old as the arts. Although the arts—in general—rely on complex interrelated production and presentation technologies, and moreover, require multifaceted contextual knowledge for deep understanding and appreciation, the artists do not always envision their works to be conceptually timeless or materially future-proof. Whether they just enjoy quick and direct communication, or are driven by the ambition to reach the indefinitely remote spatiotemporal continuum, nothing meaningful is forever in the entropic universe. Demonstrating human wit, proteanism and creativity as the rapid generators of unpredictable and highly variable alternatives, the arts are particularly prone to decay.45 A classic example is Leonardo da Vinci’s intensive experimentation with ideas and technology, which resulted in many unfinished works, and in the accelerated deterioration of his masterpieces. In that sense, the current elusiveness of archival solutions for generative art confronts us with the ultimate impossibility to unconditionally preserve the objects, events and other cultural products that carry symbolic value.

Exploring the human universals such as concepts of time, death and vanity, the artists have also appreciated the cultural porosity of art and understood that an artwork lives and dies just I believe that a picture, a work of art, lives and dies just as we do.” Baudson, “An interview with Marcel Duchamp” ']as we do.46 Artworks vary not only in material resilience but also in emotional, narrative, informational, exploratory, cognitive or political impact and relevance. They are not equally interesting or engaging and their values are not fixed. Ideally, this instability of artistic mental worth reflects scientific principles and epistemological assets such as critical thinking and testability, but the capricious status of the artists and the artworks is often affected by fancy, fashion and authority appeal. The instability of artistic mental worth also evokes the reductive economy of the conscious experience, which suggests that perceptive brevity and forgetting may be evolutionary adaptive.47 But transience, erasure and forgetting are probably not beneficial for the evolution of human society. Cultural memory and preservation build up the infrastructure for progress, development and betterment of civilisation. They provide contextually efficient access to the functional and well-organised accumulated information, which is essential for fostering creativity and learning, for deepening our understanding of what it means to be human, and for improving the sense of our place in nature.

Save and Open As...

Contemporary generative art is a unique repertoire of creative approaches that reveal the crucial features of the digital paradigm and motivate our critical thinking about digital culture. They engage the fundamental ideas, logic and functionality of digital technologies humorously, intelligently and proactively, through bricoleur style experiment and playful exploration. These conceptual and methodological qualities are essential for establishing deep insights into the relevant aspects of our world, but at the same time they make generative artworks difficult to preserve and represent.48

Contemporary generative practices expand, enrich and enhance the already proven cultural relevance of new media art, and require the adequate institutional, academic, educational, financial and technical support.49 The first wave of new media art museology has funded the infrastructure for systematic study, preservation, representation and promotion.50 In addition, we need to address the specific current issues, trade-offs and risks, and to anticipate the potentials of the emerging generative art. Centralisation, exclusivity and monopolistic standardisation should be avoided because a diversity of approaches and initiatives offers higher accessibility, versatility in discovery, and better archival security.51 The optimal strategy would be to instigate, fund, connect and coordinate a multitude of platforms and projects of different scales and scopes into a robust network for archiving, distributing, transferring, and exhibiting new media and generative art.

Footnotes

1 Cahill 20-24

2 Galloway

3 Scott 30-34

4 Boyle-Singfield

5 Miller 300-340

6 Irational.org

7 Ljudmila.org

8 V.A. “iSee”

9 V.A. “Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc.”

10 Blas

11 Hill and Hofstadter

12 Fry

13 Warthon

14 Keith-Soo 525

15 Galanter 225-245; Arns; Quaranta 1-7; Boden and Edmonds 21-46; Watz 1-3; Pearson 3-6

16 Dorin et al. 239–259

17 Grba 200-213

18 Weibel 21-41; Rosen 27-43

19 Grba 200-213

20 Arns; Watz 1-3

21 Giovacchini and Sklar 2

22 Claude Lévi-Strauss 13

23 Mambrol

25 Gere, “New Media”

26 Paul, New Media 4-7

27 Epler

28 Wedekind

29 Zeilinger

30 Castells 176-180

31 Cabell and Huff

32 Cirio “Google Will Eat Itself”

33 Cirio “Face to Facebook”

34 Gleisner “Paolo Cirio’s Lovely Faces”

35 !Mediengruppe Bitnik

36 Cherubini

37 Maigret and Howell; Cox

38 “Take a Bullet for This City,” Vimeo

39 Richardson; Amazon’s Mechanical Turk is a platform that facilitates serving the Human Intelligence tasks to the ‘workers’ on the Internet to complete for a certain price

40 The algorithm extracts tags from the images using Clarifai’s convolutional neural networks, blows them up into paragraphs using a lexical relations database ConceptNet and a flexible template system. It knows what to write because it sees concepts in the image and relates those concepts to other concepts in the ConceptNet database. The template system enables the code to build sentences that connect those concepts together (Merchant)

41 Eltes

42 The current post-digital art nomenclature includes the terms ‘post-media’ and ‘post-Internet art’

43 BBC “Hypernormalisation,” 2016

44 Paul 2016

45 Miller 405

46 As Marcel Duchamp remarked in a 1966 interview: “[…] I believe that a picture, a work of art, lives and dies just as we do.” Baudson, “An interview with Marcel Duchamp”

47 Nørretranders 23-27, 124-144

48 Whether these qualities make generative artworks intellectually superior to some of the more palatable layers of contemporary art is the matter of individual taste and experience

49 Gere 2008, 79-115; Rosen 27-43

50 V.A. “Digital Art and the Institution” 461-596

51 Ippolito 537-552

References

Arns, Inke. “Read_me, run_me, execute_me. Code as Executable Text: Software Art and its Focus on Program Code as Performative Text.” Medien Kunst Netz website, 2004, http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/generative-tools/read_me/1/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Baudson, Michel. “An interview with Marcel Duchamp.” Edited transcript of the interview with the artist, filmed by Jean Antoine in 1966 (translated by Sue Rose). The Art Newspaper, No. 27, April 1993, http://ec2-79-125-124-178.eu-west-1.compute.amazonaws.com/articles/An-interview-with-Marcel-Duchamp/29278. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Blas, Zach. “Facial Weaponization Suite.” Zach Blas, 2011-2014, http://www.zachblas.info/works/facial-weaponization-suite/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Boden, Margaret, and Edmonds, Ernest. “What is Generative Art.” Digital Creativity, 20, (1-2), 2009, pp. 21-46.

Boyle-Singfield, John. “Erased Cory Arcangel Website.” John Boyle-Singfield, 2013, https://johnbsingfield.github.io/erased-arcangel/.

Bunting, Heath. n.d. Irational.org. http://www.irational.org/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Cabell, Mimi and Huff, Jason. “American Psycho.” Mimi Cabell, 2012, http://www.mimicabell.com/gmail.html. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Cahill, James Leo. “...and Afterwards? Martin Arnold’s Phantom Cinema.” Cinema, Special Graduate Conference Issue, Spectator 27: Supplement, 2007, pp. 20-24.

Castells, Manuel. The Information Age Vol. 1: The Rise of the Network Society. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Cherubini, Matthieu. “Afghan War Diary.” Matthieu Cherubini, 2010, http://mchrbn.net/afghan-war-diary/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Cirio, Paolo. “Google Will Eat Itself.” Paolo Cirio, 2005, https://paolocirio.net/work/gwei/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

———. “Face to Facebook.” Paolo Cirio, 2010, https://paolocirio.net/work/face-to-facebook/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Ćosić, Vuk. Ljudmila.org., http://www.ljudmila.org/~vuk/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Cox, Geoff. “Real-Time for Pirate Cinema.” PostScriptUM, No. 20, Aksioma Institute for Contemporary Art, 2015, http://aksioma.org/pdf/aksioma_PostScriptUM_20_ENG_Maigret.pdf. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Dorin, Alan, McCabe, Jonathan, Monro, Gordon and Whitelaw, Mitchell. “A Framework for Understanding Generative Art.” Digital Creativity, 23, (3-4), 2012, pp. 239–259.

Eltes, Jonas. “Lost in Computation.” Jonas Eltes. 2017. https://jonaselt.es/projects/lost-in-computation/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Epler, Matthew. “ReCode.” ReCode project website, 2012. http://recodeproject.com/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Fino-Radin, Ben. “The Nuts and Bolts of Handling Digital Art.” A Companion to Digital Art, edited by Christiane Paul. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2016, pp. 516-536.

Fry, Ben. “Video Experiments.” Ben Fry, 1998. https://benfry.com/video98/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Galanter, Philip. “What is Generative Art? Complexity Theory as a Context for Art Theory.” VI Generative Art conference Proceedings, edited by Celestino Sodu. Milan: Domus Argenia, 2003, pp. 225-245. http://www.generativeart.com/on/cic/papersGA2003/papers_GA2003.htm. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Galloway, Alexander. “Jodi’s Infrastructure.” E-flux Journal, 2016. http://www.e-flux.com/journal/74/59810/jodi-s-infrastructure/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Gere, Charlie. “New Media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age.” Tate Research Papers, London: Tate, 2004. http://www.tate.org.uk/file/charlie-gere-new-media-art-and-gallery-digital-age. Accessed 29 April 2019.

———. “The Digital Avant-garde.” Digital Culture. London: Reaktion Books, 2008, pp. 79-115.

Giovacchini, Saverio and Sklar, Robert. Global Neorealism: The Transnational History of a Film Style. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2013.

Gleisner, Jacquelyn. “Paolo Cirio’s Lovely Faces.” Art 21, 12 Aug 2013. http://magazine.art21.org/2013/08/12/new-kids-on-the-block-paolo-cirios-lovely-faces/#.XMLlPKQRVPY. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Grba, Dejan. “Get Lucky: Cognitive Aspects of Generative Art.” XIX Generative Art Conference Proceedings, edited by Celestino Sodu. Venice: Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, 2015, pp. 200-213, http://dejangrba.dyndns.org/lectures/en/2015-get-lucky.php. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Hill, Joe and Hofstadter, Douglas R.. Jason Salavon: Brainstem Still Life. Bloomington, IN: School of Fine Arts Gallery, Indiana University and LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore, 2004.

“HyperNormalisation.” Directed by Curtis, Adam. BBC TV documentary, 2016. 00:07:10-00:10:36

Ippolito, Jon. “Trusting Amateurs with Our Future.” A Companion to Digital Art, edited by Christiane Paul. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2016, pp. 537-552.

Keith-Soo, Chin-En. “Hueue.” XX Generative Art Conference Proceedings, edited by Celestino Sodu. Generative Design Lab, Milan: Politecnico di Milano University / Rome: Argenia Ass, 2017, pp. 525.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. The Savage Mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Maigret, Nicolas and Howell, Brendan. “The Pirate Cinema.” The Pirate Cinema project, 2012, http://thepiratecinema.com. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Mambrol, Nasrullah. “Claude Lévi Strauss’ Concept of Bricolage.” Literary Theory and Criticism, 2016, https://literariness.org/2016/03/21/claude-levi-strauss-concept-of-bricolage. Accessed 29 April 2019.

!Mediengruppe Bitnik. “Random Darknet Shopper.” !Mediengruppe Bitnik website, 2014, https://wwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww.bitnik.org/r/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Merchant, Brian. “This App Translates Your Photos into Stories.” Motherboard: Tech by Vice, 14 Apr 2015, https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/8qx7q3/the-app-that-translates-your-pictures-into-words. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Miller, Geoffrey. The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature. New York, NY: Anchor Books/Random House, Inc, 2001.

Nørretranders, Tor. The User Illusion: Cutting Consciousness Down to Size. New York, NY: Penguin, 1999.

Paul, Christiane, New Media in the White Cube and Beyond: Curatorial Models for Digital Art. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008, pp. 4-7.

———. “Collecting the Digital — Materials, Markets, Models.” Media Art and the Art Market Symposium, LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz, 2016, http://interface.ufg.ac.at/blog/media-art-and-the-art-market-speakers/#Paul. Video recording, Accessed 29 April 2019. https://vimeo.com/192670584. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Pearson, Matt. Generative Art. Shelter Island, NY: Manning Publications, 2011, pp. 3-6.

Quaranta, Domenico. “Generative (Inter)Views: Recombinant Conversation With Four Software Artists.” ed. C.STEM. Art Electronic Systems and Software Art. Turin: Teknmendia, 2006, pp. 1-7.

Richardson, Matt. “Descriptive Camera.” Matt Richardson’s website, 2012, http://mattrichardson.com/Descriptive-Camera/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Rosen, Margit. 2011. “The Art of Programming: The New Tendencies and the Arrival of the Computer as a Means of Artistic Research.” A Little-Known Story about a Movement, a Magazine, and the Computer’s Arrival in Art: New Tendencies and Bit International, 1961-1973, edited by Margit Rosen. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, pp. 27-43.

Scott, Andrea K. “Futurism: Cory Arcangel Plays Around with Technology.” The New Yorker, 30 May 2011, pp. 30-34, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/05/30/futurism. Accessed 29 April 2019.

“Take a Bullet for This City.” Vimeo, uploaded by Luke DuBois, 2014, https://vimeo.com/110217245. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Taylor, Grant D. When the Machine Made Art: The Troubled History of Computer Art. New York and London: Bloomsbury Press, 2014.

V.A. “Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc.” Jennifer Lyn Morone, Inc., 2014, http://jenniferlynmorone.com/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

———. “Digital Art and the Institution.” A Companion to Digital Art, edited by Christiane Paul. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2016, pp. 461-596.

———. “iSee.” 21st Century Digital Art, 2017, http://www.digiart21.org/art/isee. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Warthon, Rhyland. “Palette Reduction.” Rhyland Warthon’s website, 2009, http://rylandwharton.com/works/palette-reduction/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Watz, Marius. “Closed Systems: Generative Art and Software Abstraction.” MetaDeSIGN - LAb[au], edited by Eléonore de Lavandeyra Schöffer, Marius Watz and Annette Doms, Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2010, pp. 1-3.

Wedekind, Joachim. “Digital Art Gallery.” Joachim Wedekind, 2014, http://digitalart.joachim-wedekind.de/dag/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Weibel, Peter. “It Is Forbidden Not to Touch: Some Remarks on the (Forgotten Parts of the) History of Interactivity and Virtuality.” Media Art Histories, edited by Oliver Grau, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007, pp. 21-41.

Zeilinger, Martin. “Pattern Recognition.” Martin Zeilinger, 2017, http://marjz.net/works/. Accessed 29 April 2019.

Essays

ERASURES: Being, Seen

Erase (v.)

c. 1600, from Latin erasus, past participle of eradere, “to scrape out, scrape off, shave; to abolish, remove.” Of magnetic tape, from 1945.1

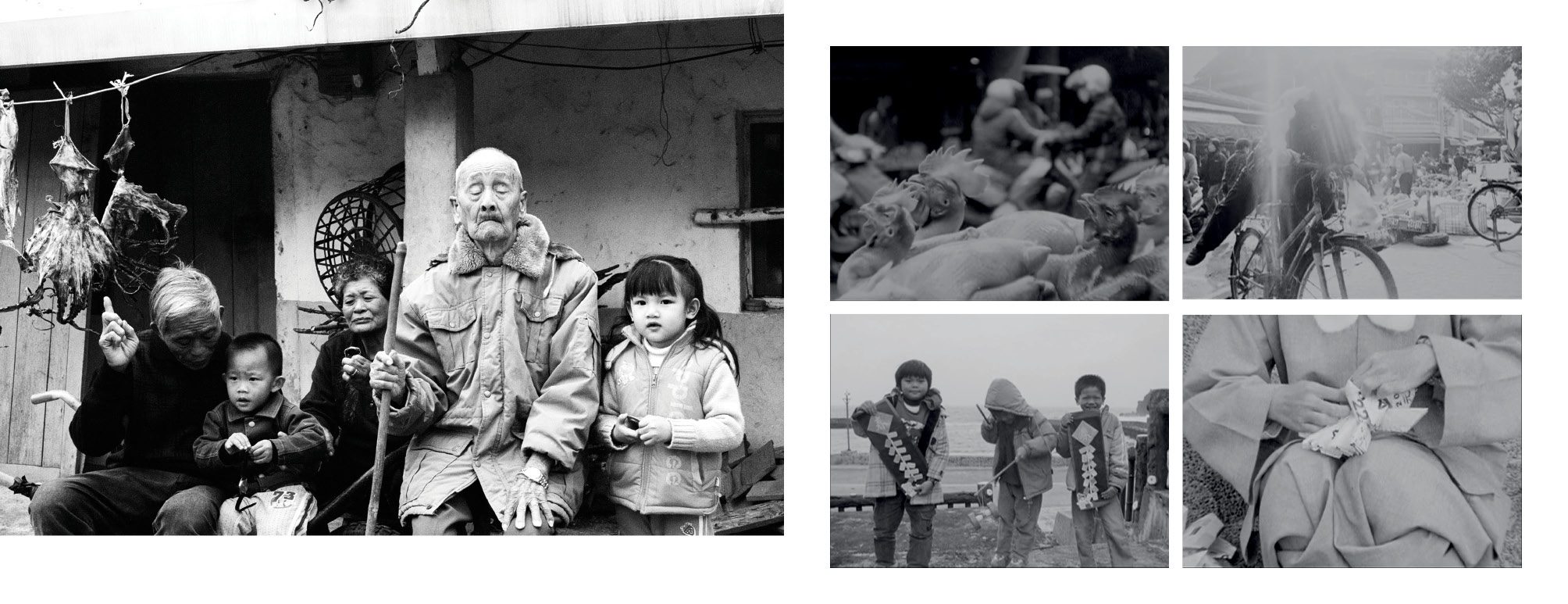

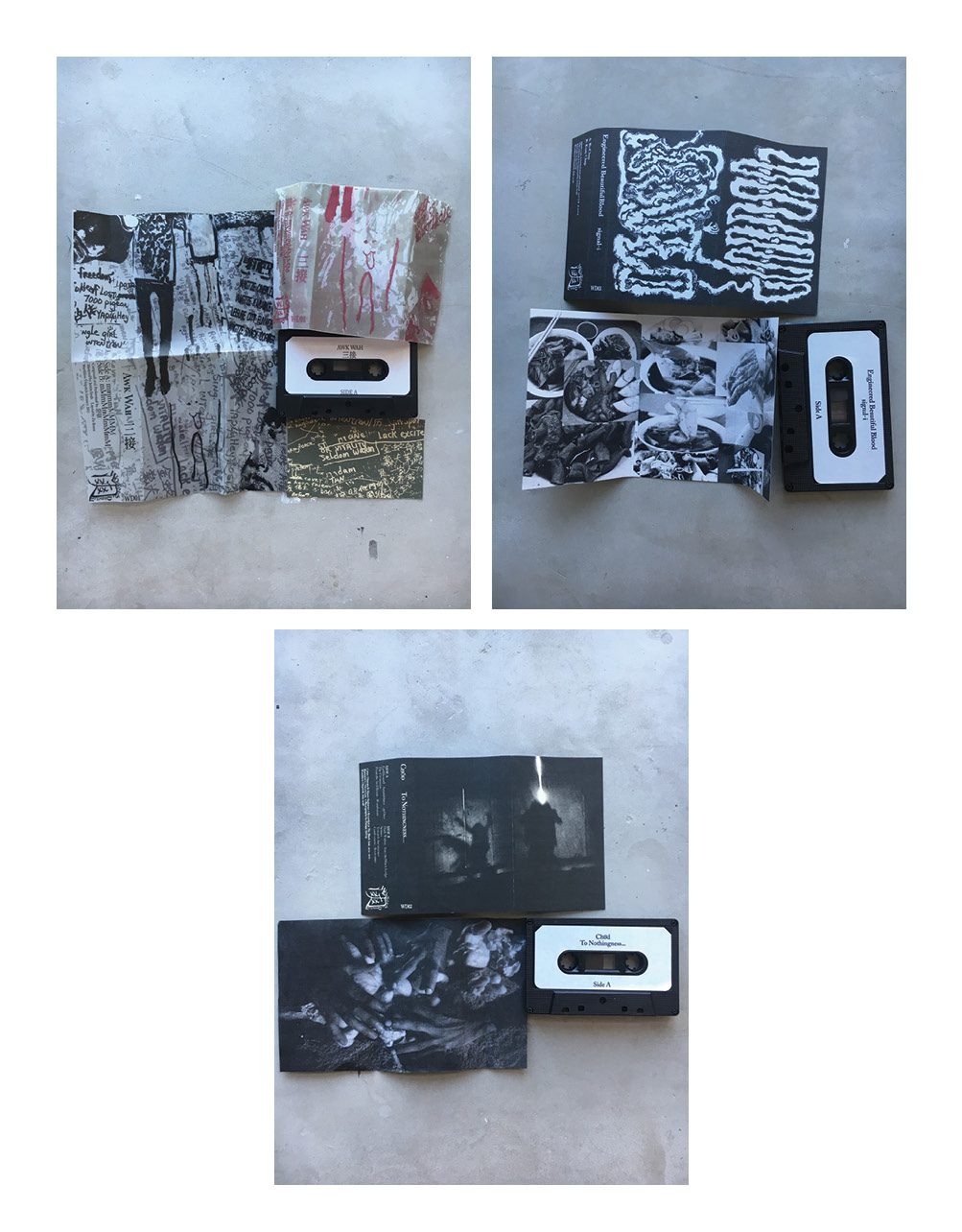

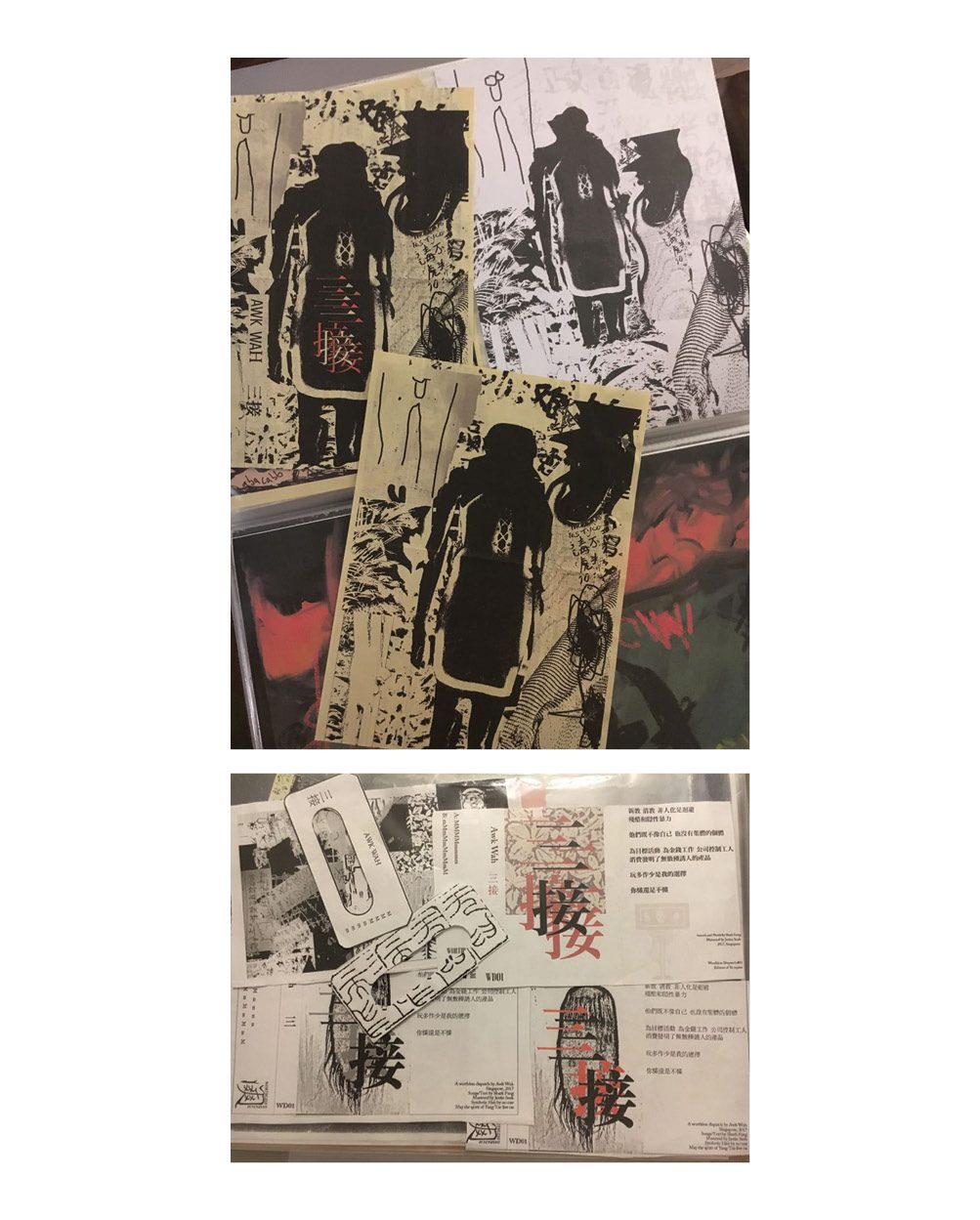

McDonalds Trabant, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Being

“Between the experience of living a normal life at this moment on the planet and the public narratives being offered to give a sense of that life, the empty space, the gap, is enormous.” – John Berger2

My grandfather was incarcerated in a Russian Gulag from age 16 to 21. Once released, he sailed the world on merchant ships, and settled in a country (Germany) he had never lived in before. In and out of prison, reluctant to submit to (absolutely any kind of) authority, he became a serious alcoholic and died young. Unless drunk he never spoke, but then no one wanted to speak to him, neither his wife nor his children, themselves also damaged people. And then there was me.

I was the only one he agreed to speak with, and so, while I lived with them during bouts of homelessness, I became the one through whom the others conversed.

My grandfather’s stories were vivid, always the same, tortured; they revealed modes of torture that damaged his body and mind forever. In response, I continually made up stories about superheroes and avengers. In their company, my grandmother and mother expected me to be like them. Stop talking. Stop making up stories. Be silent. Be silent. After all, they were silent too. They could not unlearn the idea that speaking was dangerous. Only my grandfather really spoke (when he chose to), perhaps at me, but certainly into me. I loved him. I was seven when he said that I, too, was torturing him with my questions, that they made holes in his belly, and he showed me that belly, which was indeed full of holes.

Towards Erasure

Today the vast majority of dominant cinema, regardless of genre, mode or even thematic concerns, feels like a childhood toy: something to hug, something to remember fondly, something that finally reassures, and which, as a result, can effectively be forgotten. It has lost its activating fuse, producing an international cinematic conservatism and passive audiences, upholding what film-maker Peter Watkins as long ago as 1967 termed the ‘monoform’: a delivery structure where all the complexities of life, society and history, regardless of the severity, mundanity or grace of the themes, are reduced into the same formal narrative engine, as predictable and recognisable as a famous fast food chain, and offering a similar ‘comfort’.

Estate, Fugitive Images

Before its workings are understood, the power of cinema is often evasive, slippery. At the opposite end (its result) is what is often termed powerlessness, a feeling that accompanies the sense of being made invisible, insignificant, a voice that does not count. However, what surfaces, closer to obstinacy, rather than resilience, is a making visible, and not in response to erasure, but regardless of it.

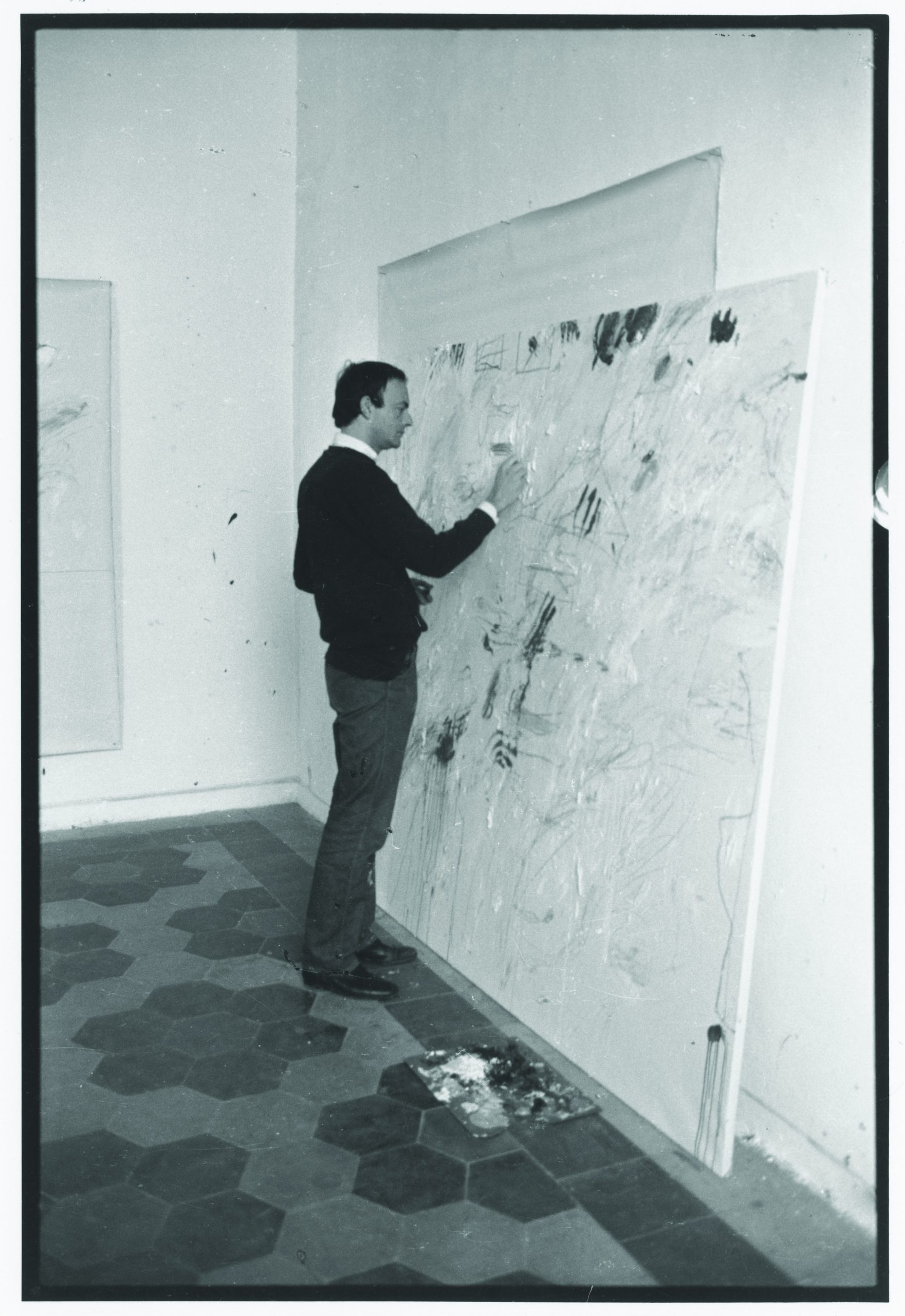

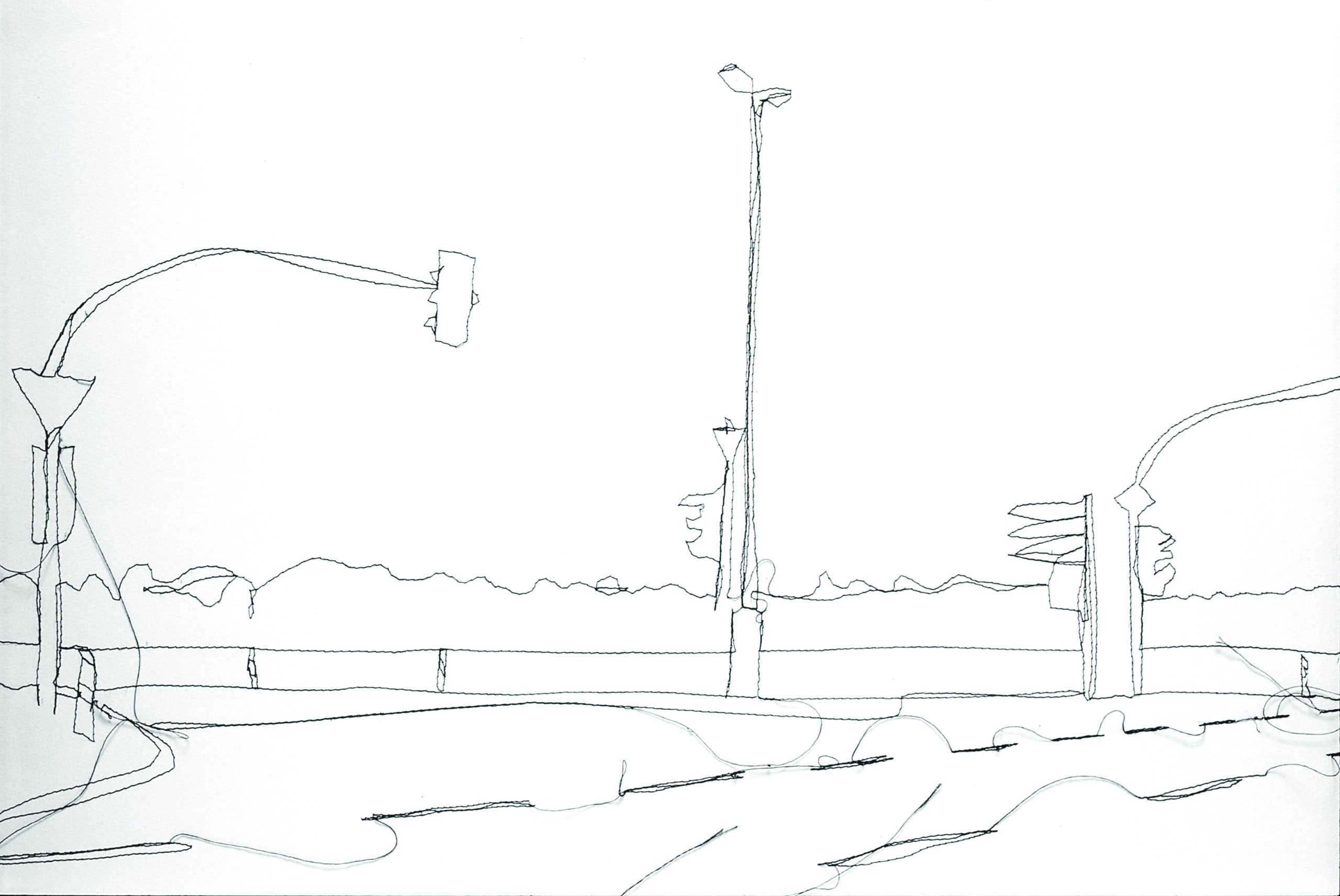

Here I will explore, though my own approach to making films, various manifestations of and challenges to power (especially in its ‘behind-the-scenes’ identity, from covert military operations to city planning). For the past 10 years my work has focussed on the often under-explored and under-expressed intersections of public and private memory, especially in relation to place, communities and to structural and political violence.

Estate, Fugitive Images

Throughout, my approach has been socially collaborative, in content, form and production. Formally, my films seek to open (for both the participants and audience) a space for consideration of the shifting border between documentary and fiction, using long-term observations, interventions in real-life situations, re-enactments, found materials, archival traces and ‘always the honouring of lived experience.’ I seek an ethically engaged, culturally resonant expression of shared humanity, and a co-existence with larger ecologies (beyond human-centred subjectivity).

So…

I have set out these criteria:

To reject the erasure of place, history, relations and difference.

To acknowledge my own lifelong experience of these concerns, and the class expectations and restrictions that accompanied my own journey into an understanding of these structural assaults.

To find a visuality that is not only in opposition to (or merged with) the erasure as we, in different ways already experience it, in our surroundings, in our bodies, in our minds, and in our ways of sensing each other.

To enable a making and embracing of an aesthetic that allows for the presence of ambiguities, of a tone that might be called troubling, unsettling (unable and unwilling fully to be reconciled or resolved) and yet, in spite of that, to voice a complex solidarity for and with each other.

To understand that each film is a form of making and briefly finding ‘home’, a moving from being-forced-to-dwell-inside one structure to making, along with others, another structure in which the existential complexity of our life in the world as we find it (and seek to make it) is allowable.*

Against Erasure of Place

Estate a Reverie (2015)

Estate, Fugitive Images

Estate, a Reverie speaks to and of a city long inhabited by a huge diversity of communities (whether focussed around ethnicity, nationality, belief, gender or sexuality, and not forgetting, of course, finance, class and vocational groupings), a territory whose complex identity is at stake within the unfolding and accelerating narrative of globalised gentrification or ‘development’. It is a zone whose buildings, functions and populations are being challenged by ‘incursionist’ forces—of speculative capital, architecture and commerce—threaten the current spectrum of ways of being in this location.

The film tries to make sense of a process that is regarded in public discourse as inevitable, one that declares public housing in its original sense to be dead, made obsolete by the market ‘choices’ of a neoliberal world, one shaped by both finance and consumer capitalism.

What is the movement, subtly, of perception, accompanying this shift? The privatised city (including militarised domestic vehicles, private healthcare, schooling, roads and more) has at its mirror image, the ‘other’. We often cannot precisely ‘see’ how power works, and mostly we do not even notice it, until we (some bodies more than others) are subjected to its full force.

Clichés and stereotypes in policy and commentary are reinforcing ideas of the abject, alongside an accompanying sectional ‘public’ fear. This instigates a further spread of the private sphere (structurally, legislatively and mentally) into the public realm, intended to make certain groups of people ‘feel’ they are not welcome: not welcome to participate, unable to, and in fact undesired. Strangers in their own time and place.

Estate, Briony Campbell

Estate, Fugitive Images

I had lived on the Haggerston estate in East London for most of my adult life and campaigned for many years alongside other residents to get the buildings repaired. Decades of neglect and intentional underfunding meant that they were in terrible condition. We were not successful in saving them and, once I knew that the estate would soon be demolished, I started filming.

It feels important to note that Estate has not been made ‘about’ this community but has been made ‘from’ it. Through a variety of filmic registers and strategies, the film seeks to capture the genuinely utopian quality of the last few years of the buildings’ existence, a period when, because demolition was inevitable, a refreshed sense of the possible, of the emergence of new, but of course time-specific, social and organisational relationships developed, alongside a revived understanding of how the residents might occupy the various built and open spaces of the estate.

Crucially, the film challenges what a documentary about housing might look like and be, even at this time of acute crisis within UK provision. I made a very conscious decision to move away from the statistical and expository towards a poetics of everyday life.

Estate focusses on the ‘structure’ of its eponymous architecture not only because it is where we lived, but also ‘how we lived.’ The film explores the multiple implications of what most explicitly defined us to other people, while simultaneously challenging that often all too monocultural definition and revealing the complexity and breadth of the population it housed. The film seeks to counter the many myths and clichés of our mainstream representation with a celebration of spirited existence and asks how we might resist being framed and objectified through externally imposed ideas towards class, gender, (dis)ability, economy and ethnicity, and even simply the building in which we sleep and wake.

Against Erasure of Difference

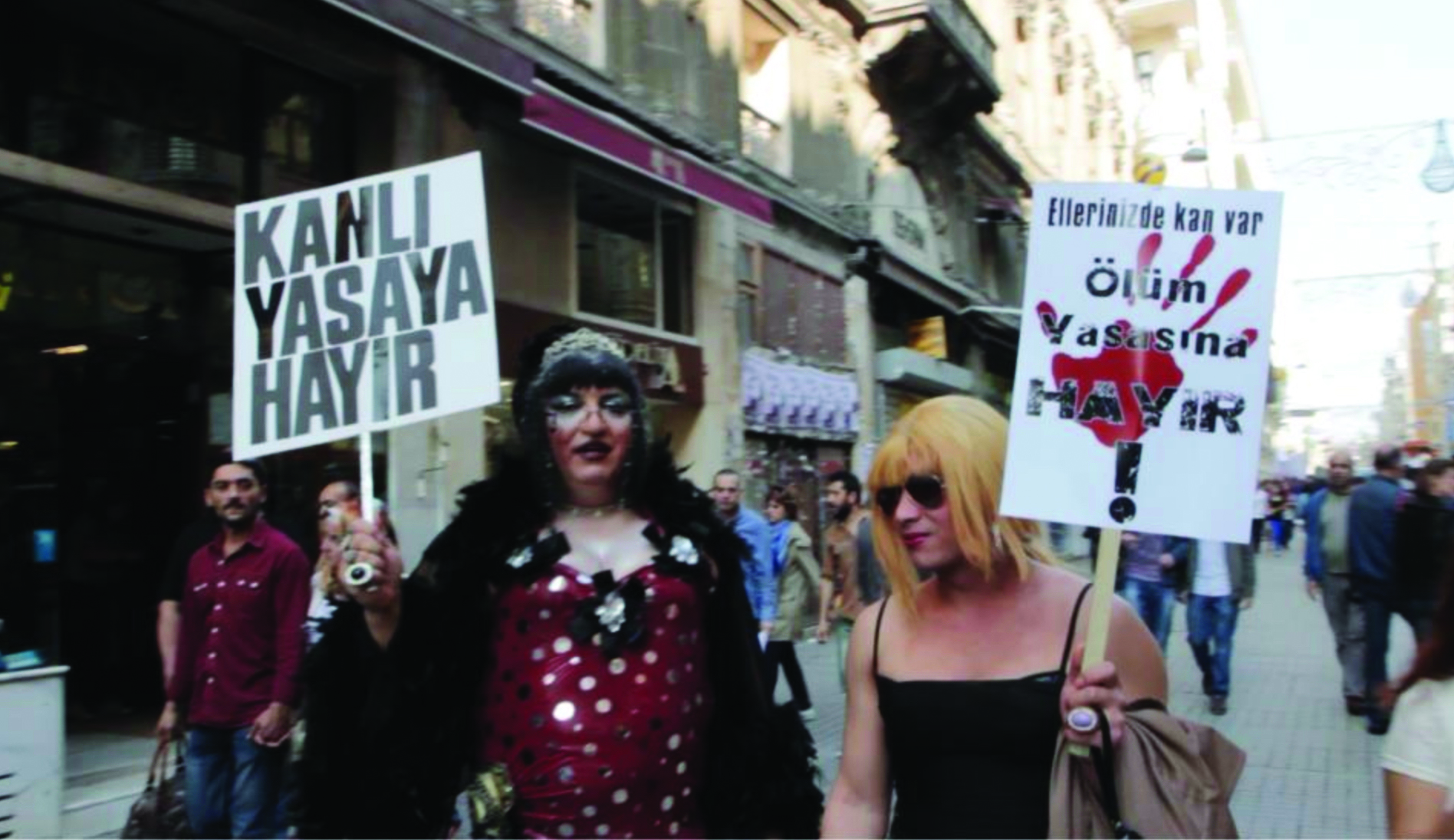

Taskafa, stories of the street (2013)

Taskafa, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Taskafa (from the Turkish: stone-head, hard-headed) is a film about memory and the most necessary forms of belonging, both to a place and to history, through a search for the role played in the city by Istanbul’s street dogs and their relationship to its human populations. Through this exploration, the film opens a window on the contested relationship between power and the public / communities of the city. It challenges categorisation (in location and identity) and charts the ongoing struggle / resistance against a single way of seeing and being.

Despite several major attempts by Istanbul’s rulers, politicians and planners over the last 400 years to erase them, the city’s street dogs have persisted thanks to an enduring alliance with widespread civic communities and neighbourhoods, which recognise and defend their right to coexist.

Taskafa, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Taskafa, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Taskafa gathers the voices of diverse Istanbul residents, shopkeepers and street-based workers, all of whom display a striking commitment to the well-being and future of the city’s street dogs (and cats), free of formal ownership but fed and cared for by numerous individuals. Navigating from the rapidly gentrifying city-centre district of Galata to the residential islands of the Sea of Marmara and beyond, Taskafa maps a history of empathy with, and threats to, these distinctive urban residents.

I had collaborated on the film with the late John Berger, whose novel King gave me the key to the story. King, a story of hope, dreams, love and struggle, is told from the perspective of a dog belonging to an economically and socially marginalised squatter community facing disappearance, even erasure. In Taskafa, this voice is gifted to a wider community and imbued with a range of perspectives: to dogs, a city and, finally, to history. Berger’s text and delivery accompany the viewer on a journey from Karaköy to Hayirsiz Ada, the island where, in the 1800s, tens of thousands of dogs were exiled to die.

Offering a moving collage of testimonials on the inestimable value of non-human populations to the emotional and psychological health of the city, together with a striking statement of witness to advocacy and persecution across the centuries, Taskafa both portrays, and embodies the spirit of protest and enduring solidarity on which it closes (with a mass demonstrations opposing the latest municipal proposals to clear the city of its street animals).

Taşkafa is not finally about dogs as such. It is about the way people seek to belong, still and ever more so now, to a larger context than themselves, one which respects other creatures and wishes them to play a significant role in their lives. The key issue is not whether we live securely, especially in its ‘official’ sense, but rather that we do not lose touch with the shared reality that surrounds us.

Against Erasure of Histories

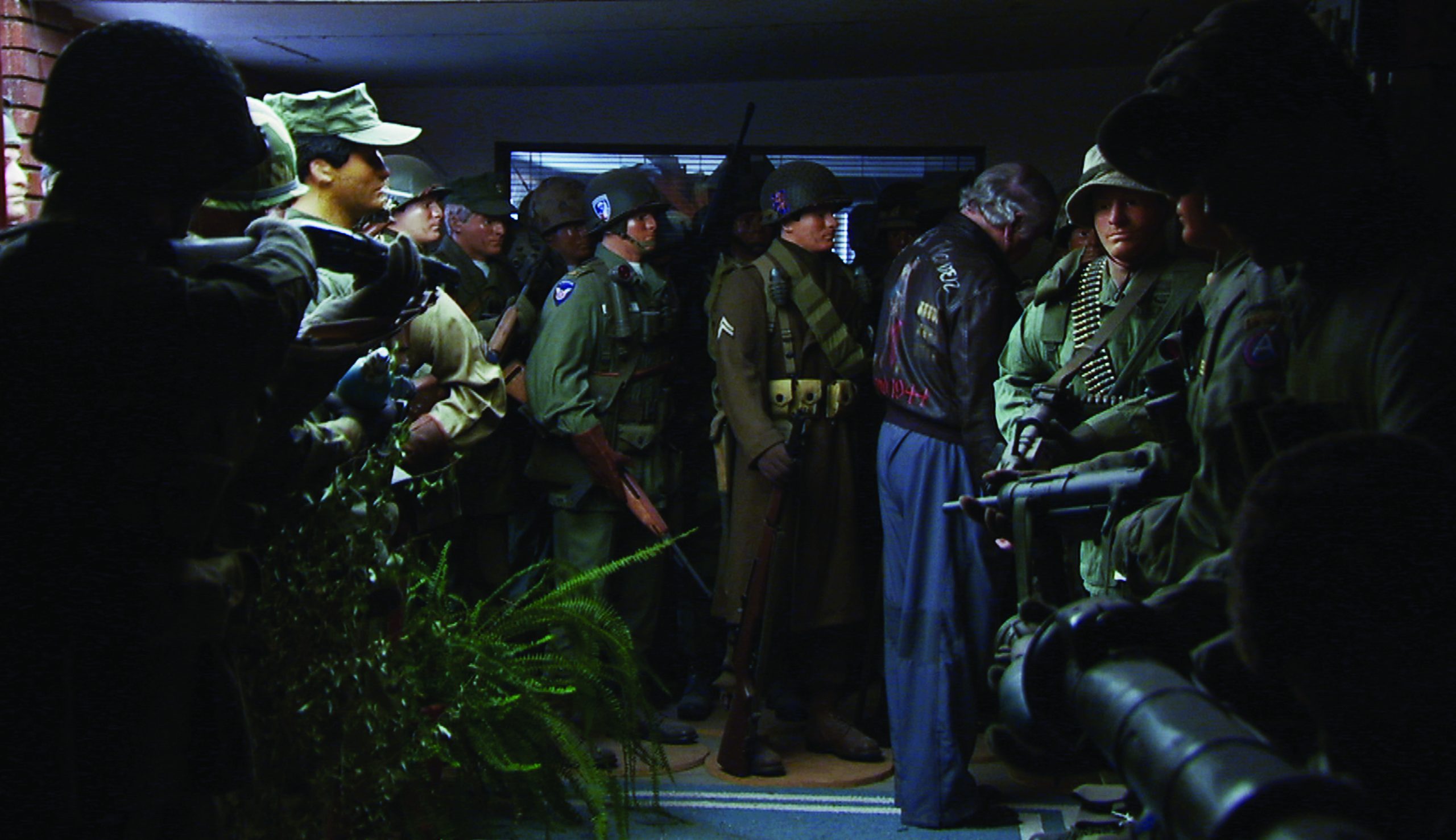

Erase and Forget (2017)

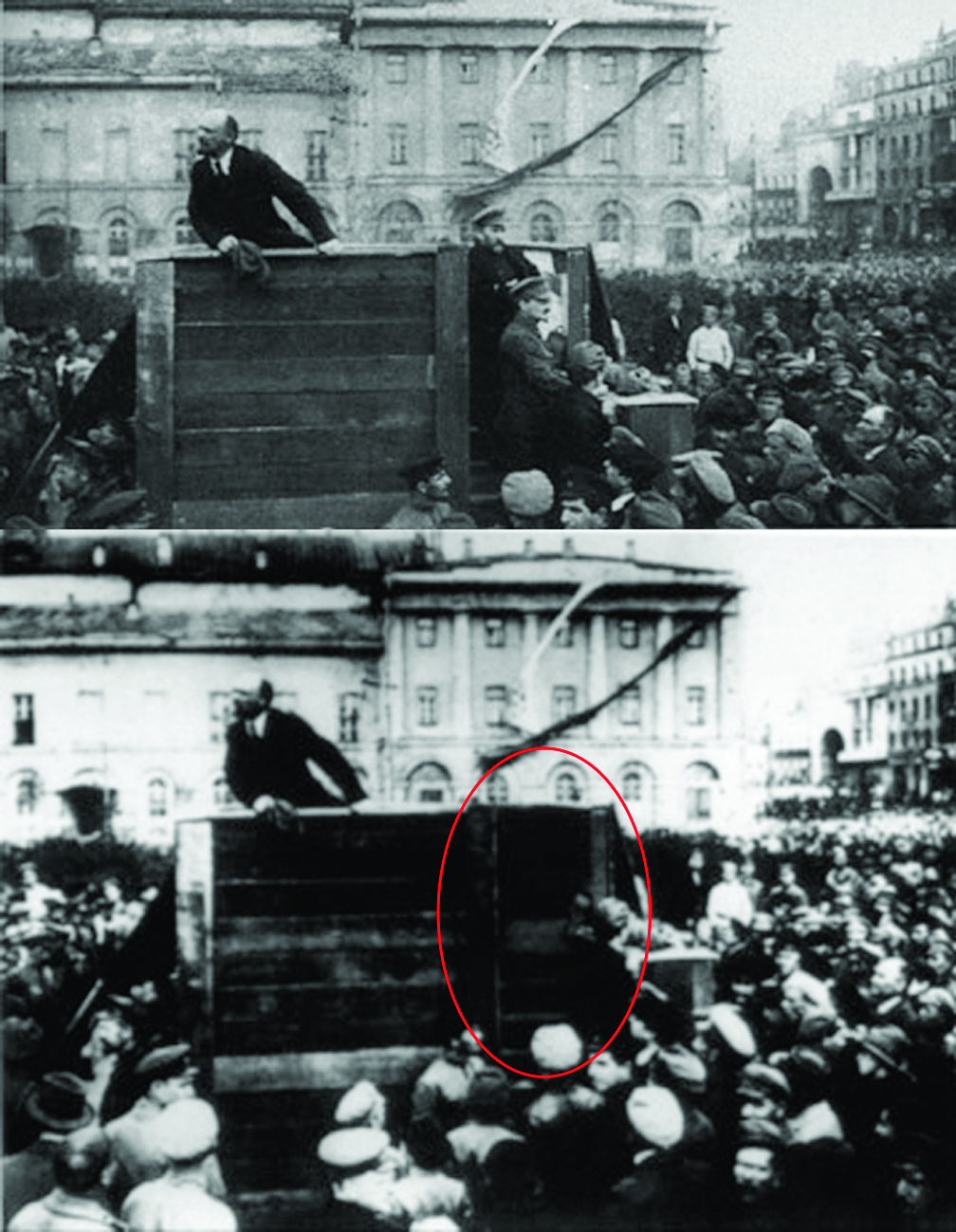

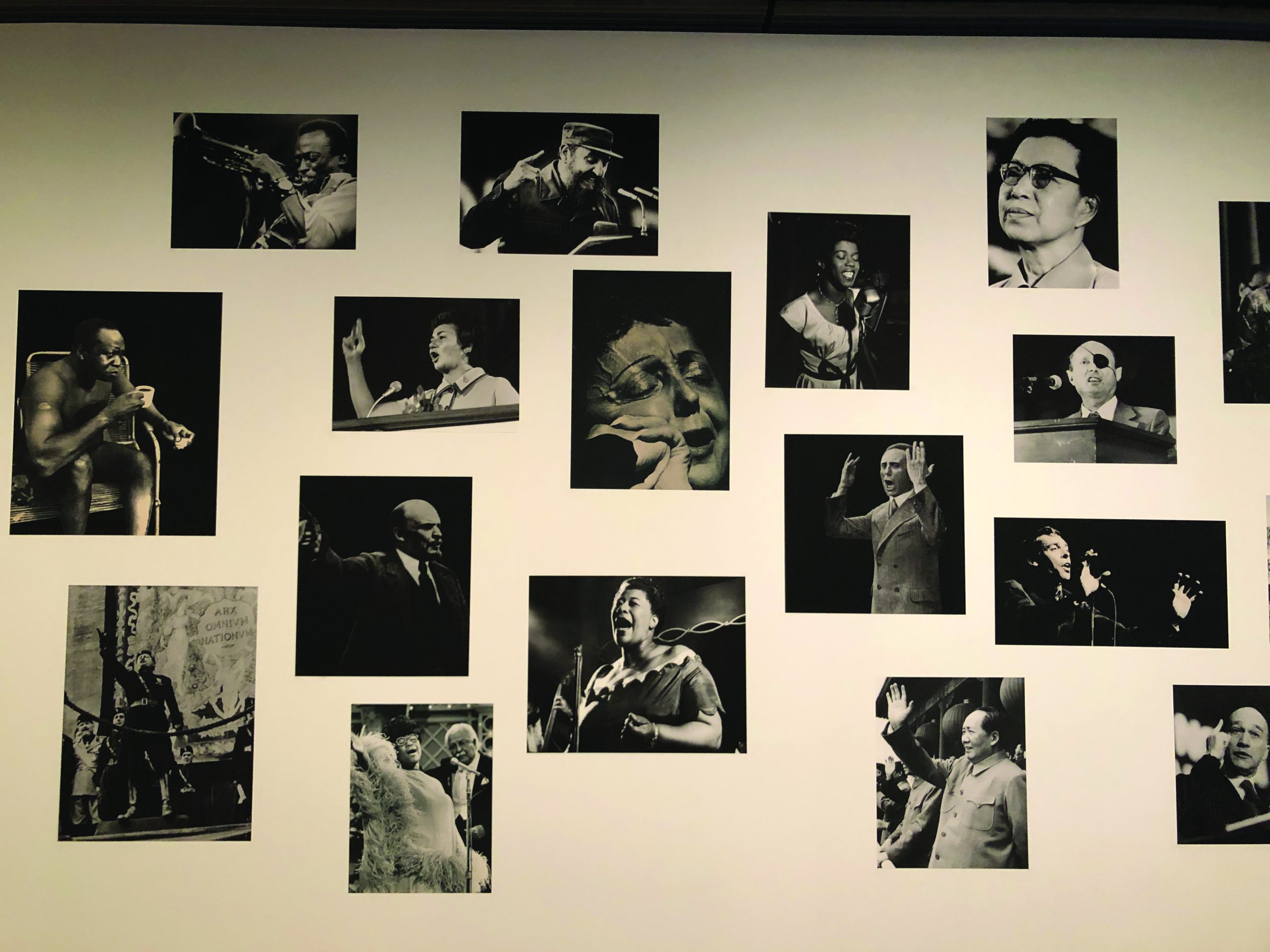

Erase. Courtesy of Bo Gritz

“You already know enough. So do I. It is not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and to draw conclusions.” – Sven Lindqvist3

Lt. Col. James Gordon ‘Bo’ Gritz turned 80 this year. ‘The American Soldier’ for the Commander-in-Chief of the Vietnam War was at the heart of US military and foreign policy—both overt and covert—from the Bay of Pigs to Afghanistan. He was financed by Clint Eastwood and William Shatner (via Paramount Pictures) in exchange for the rights to tell his story. Their funding supported his ‘deniable’ missions searching for American POWs in Vietnam. He has exposed US government’s drug running, turning against the Washington elite as a result. He has stood for President, created a homeland community in the Idaho backlands and trained Americans in strategies of counter-insurgency against the incursions of their own government. What does it mean to have lived a life like this? Gritz’s life is a contested, contentious and very public one, unfolding glaringly in the media age. It is a life made from fragments, from different positions, both politically and in terms of their mediation.

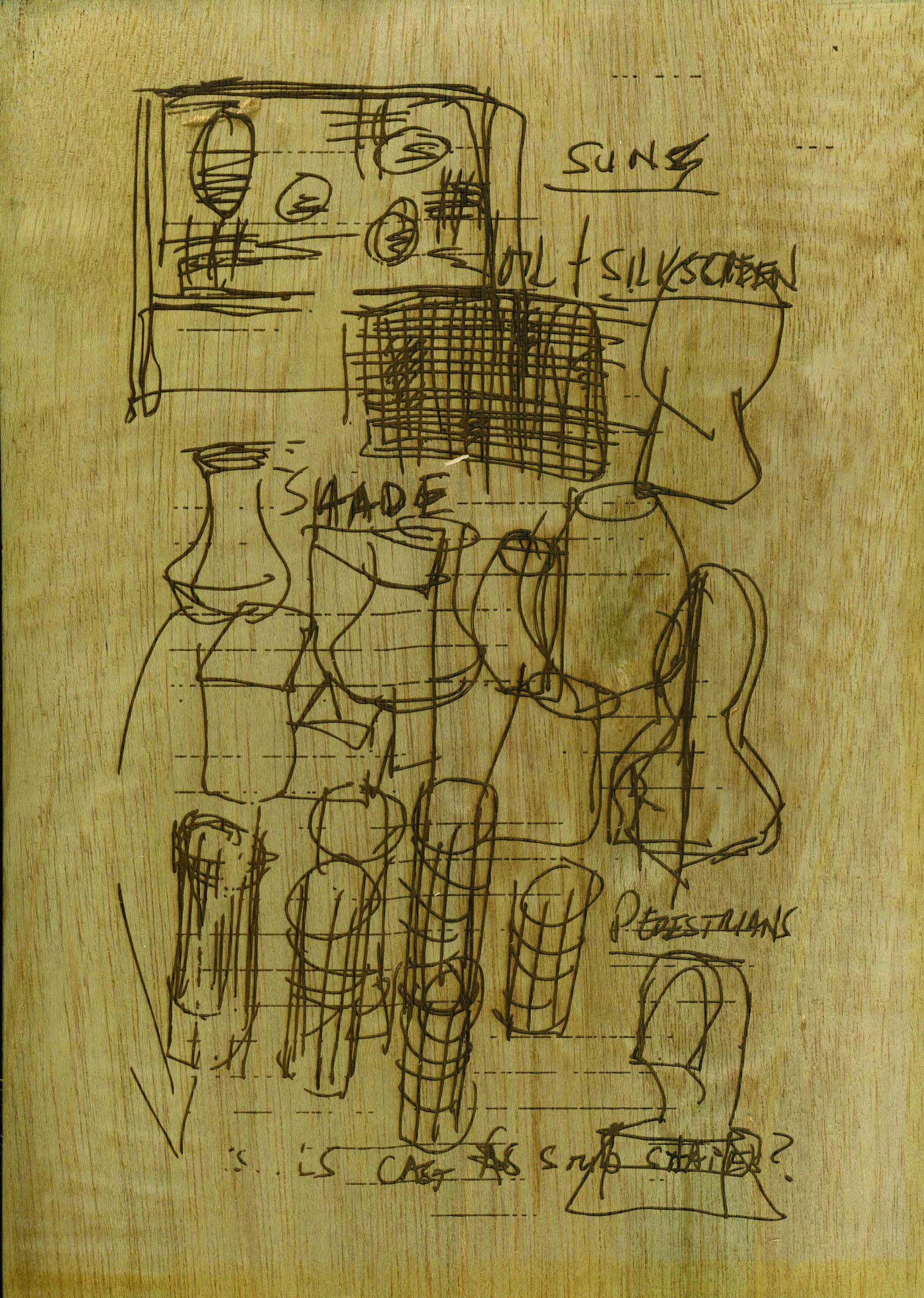

Lights, Camera…

In Erase and Forget my interest is not merely in what ‘really happened,’ but in the actor’s historical becoming, the context of which remains contradictory, able to be assembled only from shards. My experiments with role-play, re-narration, re-enactment and the montage of ‘document’ and ‘fiction’ have been part of a methodological quest to find an expression that promises no immediate or direct access to historical truth, but whose processes articulate and analytically ‘perform’ the dramatic, narrative and generic conditions of the production of historical truth and its personnel.

It is a way of exploring relationships between image, memory and historical representation in a context—covert operations—where such explorations are fraught. It is therefore a film about films, the making of historical actors and ‘superheroes’ in order to justify an enemy. And, crucially, it investigates structures of concealment instead of invisibility, where a profound unmaking of the possibility of seeing with our own eyes is in operation.

The imbrications of Hollywood mythmaking and national policy formation reach back to the first half of the last century. It was not merely that Hollywood directors were seized by the hubristic urge to shape the extraordinary dreams and everyday opinions of the masses, but rather that figures within the administration actively sought to harness such hubris.

Here, fiction cinema offers an access point that allows for both the recovery of logistical detail and the plotting out of a historical mise-en-scene of which such details are elements. Fiction creates reality. Hollywood and political structures in the United States are tightly knit. On a material level, there are exchanges of personnel and funds. Hollywood regularly employs (often retired) covert operators and military staff as advisers, and the story rights of military operations often become the properties of major studios. Where the purchase of such rights is, by definition, often after the fact, on occasion funding precedes the event.

The flow of finance and support between Hollywood and the military is not unidirectional. The Pentagon contributes by providing army assistance (advisers, helicopters, use of bases, etc…) to productions that it deems supportive of US policy. Such films inform the climates of public opinion within which that policy operates. They open imaginative spaces and arenas of ethical consideration in which certain kinds of military operations are validated. Furthermore, Hollywood cinema serves as a curious, discursive space for policy makers (and thus for speechwriters as well as scriptwriters). Ronald Reagan, on numerous occasions, publicly drew on the Rambo series to articulate his foreign policy vision and configure his political aspirations.

…(Covert) Action!

Gritz was part of a world where deniability lies at the forefront of action on the uncertain line between knowing and unknowing. The spectral nature of covert operations lies in their being, officially, ‘neither confirmed, nor denied.’ Thus, the spectral is produced by official discourse, but admissible to it only as that which cannot be admitted. However, rather than a product of official denial, it is the outcome of ‘deniability’. This involves not the denial of a particular event but denying official authorisation of an event.

Dislocating action and intention, cause and effect, creates a shadow realm from which strategic operations march forward like zombies—an operation appears to have been carried out in the absence of an originating order. The action is spectral in as much as it seems to escape the laws of causality that govern the rest of the world—it is an effect without identifiable cause.

The spectral can be thought of as power’s penumbra - precisely an effect of the potential to ‘project power.’ Indeed, the potential for covert operations is variously publicised: covert operations are an acknowledged instrument of policy. Thus, spectrality is more an effect of an administration’s covert operations capability than of any particular operation. Thus, the spectral issues from the encounter between a highly publicised capability and the mechanics of deniability.

While any given mission may be invisible, the spectral threat of those missions is often broadcast in a spectacular fashion. The very visibility of Hollywood renditions of covert operations does nothing to diminish their spectrality. On the contrary, the spectral subsists in the spectacular: if it is the penumbra of power, it is also the shadow of the spectacle.

Covert operations are institutionally accepted as an essential instrument of government policy and today, of course, increasingly privatised. Thus, without the need to invoke shadowy conspiracies, the very machinery of democratic governance produces a host of spectres.

When an image (page 24) of Gritz and his Cambodian mercenaries who fought the ‘secret war’ in Laos was published in General Westmoreland’s memoirs A Soldier Reports (1976), Francis Ford Coppola, making Apocalypse Now (1979) (based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) and narratively transplanted to the Vietnam War) asked for permission to use this image, with the intention that Marlon Brando’s (who played the renegade US Colonel, Kurtz) face be pasted over Gritz’s. This request was refused by the Department of the Army.4

In 1979, Gritz had given up his formal military career to prepare for his prisoner-of-war recovery mission, Operation Lazarus (1982-83). Lazarus was short of money, and this shortfall was collected from various sources. William Shatner, otherwise known for his role as Star Trek’s Captain Kirk, helped bridge the gap by providing US$10,000 in exchange for the rights “to tell his (Gritz’s) life story.” Clint Eastwood provided the remaining US$30,000 in return for an unofficial option on the story rights to the mission itself.

Thus, a future history was at once made possible and purchased. The story of prisoners of war brought home, or in other words, returned, through the initiative of one man operating beyond the law and without official sanction, was just the kind of patriotic tale of heroism and redemption that Hollywood was hungry for. However, a restaging of the mission (i.e. the Hollywood film) depended very much on an initial staging congruent with the conventions and dictates of its Hollywood paymaster.

Erase, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Operation Lazarus generated sensationalised news coverage on all three major US networks, as well as triggered a campaign to discredit Gritz. He claimed he was prepared for the smears and suggested that his mission, at the highest levels, had a different ultimate objective: was not my idea. I got a letter. Perot admits General Tighe called me to conduct a covert mission into Laos. They thought that because I was Westmoreland’s soldier, if I say there aren’t any, then there was closure on this issue.” See also Gritz’s testimony before the Senate Select Committee Testimony & Depositions, November 23rd, 1992: General Eugene Tighe, Director, DIA, requested H. Ross Perot sponsor a private effort to determine whether or not any U.S. POWs were left alive. “Perot called me to his EDS, Dallas office in April 1979. He instructed me accordingly: ‘I want you to go over there and see everyone you have to see, do all the things you need to do. You come back and tell me there aren’t any American prisoners left alive. I don’t believe it and I’m not interested in bones.’”']“not to recover prisoners of war but to confirm their non-existence.”5 Effectively, what the administration wanted was a spectacular illustration of absence, and the high visibility of ‘nothingness’ was intended to banish the spectres of those supposedly still missing. So, having initially conjured the spectres as a means of prolonging the war and then as a means of negotiating the peace, the administration now wanted to banish those spectres through the spectacle of the covert operation.

Of course, the very notion of a spectacular covert operation is paradoxical. As is the fact that Gritz was chosen to lead the secret mission precisely because of his visibility. In the end, Gritz never returned with any prisoners, but each return was haunted by the spectre of prisoners that his very missions were involved in producing.

In the same period, William Casey (CIA Director during the Reagan years) brought in some of the country’s top public relations firms to advise him on how to sell his two pet projects—supporting the Contras in Nicaragua and the Afghan Mujahedeen—to a dubious American public. He called this “perception management.”6

Ronald Reagan, at the 1988 annual Republican Congress fundraising dinner said, “by the way, in a few weeks, a new film opens, Rambo III. You remember in the first movie Rambo took over a town. In the second, he single-handedly defeated several Communist armies, and now in the third Rambo film, they say he really gets tough. It almost makes me wish I could serve a third term.”7

There is another, rather less widely distributed film that stands as testimony to the Reagan government’s dedication to the ‘Gallant People of Afghanistan.’ Untitled and shot on Super 8 sound stock in the fall of 1986, it is the record of a ‘secret’ training programme for Afghan Mujahedeen on US soil.

Most of the training was carried out in a disused mine in Sandy Valley, not far from the small desert town in which Gritz was and remains resident. At one stage, the footage shows Gritz winding up a detonator cable leading to a huge plastic container-bomb that explodes in spectacular fashion. It leaves behind an enormous crater in the desert earth and is cause for enthusiastic cheering from a largely off-screen crowd. A little further into the reel, Gritz, presiding over a bucket of ball bearings, instructs his traditionally clad Afghan trainees in the making of homemade claymore mines. Explaining what will happen once the many ball bearings penetrate their targets, he makes the allusive suggestion to “just think of it as Hollywood.” These bomblets are baked in apple pie tins and then detonated in close proximity to human-shaped paper targets. After the explosion, Gritz inspects the targets and shouts triumphantly: “All the Commissars are damaged!”

After the post-9/11 US investigation of Afghanistan, editors at a local US news outlet, Channel 8, cut their bulletin item to footage of Rambo. The voiceover explains the unorthodox editing: “You’ve heard of the Hollywood Rambo, who ploughed the cinematic jungle of South East Asia looking for American POWs.” On screen, we see Rambo in a shooting frenzy, firing a 50mm cannon. Rambo shoots the gun from his hip, which is followed by a match-cut to Gritz shooting an even bigger gun, also from the hip. As Gritz shoots, the television voiceover continues: “We’ll meet the real deal, Bo Gritz.”8 The report then went on to reveal the American locale of the Afghan training.

Television conflates Gritz with the fictional Rambo in order to make sensational news. By conflating them, and thus sensationalising the covert, what Channel 8 does is to occlude the conditions by which Gritz’s Afghan training was made. Everything singular about this film is erased, including the terrible events from which it emerged. By producing Gritz as ‘the real deal,’ television produces the irrecoverable historical real (i.e. the past) as merely a parasitic supplement of fiction.

Spectacular realist fiction, then, precedes the events upon which it is ostensibly based. And this is something of an inevitability in a mass media environment which rehearses as well as scripts the conditions of sociability, namely those common fictions through which the world can be apprehended, those conventions that allow for a popular imagination to distance itself from the violence that underpins it.

The violence of Channel 8’s treatment of Gritz’s Afghan training film seeks to erase its detailed relationships with the past—the discursive conditions by which it can be received as evidence of something other than the spectacular performance of a fictionalised character. James ‘Bo’ Gritz becomes the ‘real’ Rambo, for the media (and to himself) because it serves the media precisely to be able to talk about ‘real life’; and it serves Gritz to reinvent himself as the ‘real deal,’ to suture himself into a mise-en-scene in which his own carefully collected documentation can be apprehended as evidence, and be celebrated as a hero. As Gritz says, “Why should I act like Hollywood when it is Hollywood’s job to act like me?”9

In summary, then, we can see how Reagan plots out his foreign policy imperatives along the trajectory of the Rambo franchise, which reciprocates by riding and intensifying the wave of euphoria generated by the apparent success of that foreign policy. There are interesting parallels between these public policy statements, the spectacular renditions of that policy’s effects, and Gritz’s own film record of one of the covert operations that embodied the policy’s strategic implementation. This record becomes an element in the public construction of Gritz’s character, used as it is in the local Channel 8 news report. This construction erases—precisely through violent spectacle—the actual violence of which Gritz was an agent. Gritz participates in this violence through the directorial relationship he forges between himself and Rambo as a fictional character, which finally entails reducing his utterances to fictional clichés.

Erase, courtesy of Bo Gritz

The word ‘secrete’ has two senses that appear to be in peculiar tension with one another: to exude, and to make secret. It is this peculiar tension that informs the relationship between spectacular representations of covert military operations in cinema and the spectral violence of the actual ‘theatres of operation.’ On the one hand, Hollywood is willing to create the conditions of possibility for covert operations so that it might then recover them in spectacular fashion. Shatner and Eastwood both funded covert missions with an eye to their future Hollywood renditions. In this sense, Hollywood has the capacity to secrete a spectral violence. But this secretion, in order that it might be successfully recovered as spectacle, must be secreted as secret. The covert operation must be ‘secret’ in order to be authentic. Here, then, the covert operation is pretext for, and projection of, its own spectacular re-enactment.

This process of secretion, however, is chiasmatic. The covert operation may, in some instances, secrete its own Hollywood creation (for example, Eastwood claims Gritz’s proposal was that he, Eastwood, stage a faux action movie production on the Thai-Laos border to serve as cover for Gritz’s mission). Here the spectral secretes the spectacular in order to make itself secret.10

It is this process of mutual secretion, of projection and reflection, that Erase and Forget aims analytically to perform. The insertion into a fictional scenario of a historical actor whose biography is purportedly the basis of that scenario’s script is a strategy that has yielded rich results. This mise-en-abyme strains the coherence of both the biographical and the fictional scripts, and in so doing, reveals the generic imperatives that guarantee these discourses’ very coherence.

Against Erasure of Relations

Here for Life (2019)

Here for Life, Zimmerman, Jackson, Artangel

A collaboration with Adrian Jackson, founder of Cardboard Citizens (a theatre company comprised of homeless and former homeless people, whose acting method is based on Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed) and the performers, Here for Life, travels alongside 10 Londoners. All have lives shaped by loss and love, trauma and bravery, struggle and resistance. They grapple with a system that is inherently stacked against them.

They dance together, steal together, eat together; they agree and disagree, celebrate their differences and share their talents. They cycle, they play, they ride a horse. The lines between one person’s story and another’s performance are blurred and the borders between reality and fiction are porous.

Here for Life, Zimmerman, Jackson, Artangel

Eventually they come together on a makeshift stage in a place between two train tracks. They spark a debate about the world we live in, who has stolen what from whom, and how things might be fixed.

We felt it important to make this film now, with those who are engaged in a daily struggle with the structural violence of our society, as they are so readily exoticised, victimised and ‘othered’ in a number of different ways through widespread and repeated cultural tropes. We worked with our troupe over a long period of time in order to work through these issues, and to allow the participants agency over their stories. So, together, we explored what stories can be told, across and beyond difference and fixed ways of seeing and feeling. Perhaps most importantly, our film seeks a tenderness in this search, in both the making and expression.

I am a perennial observer, wishing to understand how images may be opened up to show us the richer variant meanings contained within them. Misconceptions about one another are largely structural, then internalised as if they were personal, inevitable traits or failings. It has so much to do with relatability. And misconceptions, of course, are shared across these intersections. This awareness played a significant role in our working with the troupe, and also with ourselves: starting from our own stories, what we share, and then how we might give life to another’s story without simply assimilating it into a dominant narrative.

Making a film with people always includes questions of (self) doubt / censorship (what we exclude because we see it from a particular position, fear, etc). This film is about storytelling in a literal as well as more associative sense, where the specifically situated, through rigorous examination and open telling, might speak to the ‘universal’, to the common ground.

For…

My intention in each work has been to create what I could call an activating metaphor; an image or concentration of form that is both actually itself undeniably in the world and also an energising metaphor of larger concerns. In Taskafa, it is the canine; in Estate, the building; in Erase and Forget, military conflict—both overt or covert—speaks to many other ruptures. And in Here for Life, the squatted performance ground holds and meets the marginalised bodies / lives of the film’s performers.

Here for Life, Zimmerman, Jackson, Artangel

I am informed here by what Angela Davis (and others) have observed about the need for new metaphors that convey the truth and lived experience of our times. She says, for example, for most women, people of colour and working-class citizens, it is much less about ‘hitting a glass ceiling’ in which reaching this far are the privilege of only those few, than it is about staying steady on a ‘collapsing floor.’ I am with those who are trying to stand.

Seen

In The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas (1973), the late Ursula K. Le Guin tells of lives lived in a city of harmony, peace and happiness. When the citizens of this settlement learn that their peace is dependent upon the condition of one child kept in darkness and squalor, initial outrage is soon followed by a general forgetfulness of this suffering. However now knowing, and unable any longer to stay within the city’s wall, some choose to walk away. Le Guin writes that: “The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away...”11

*End Note

Three of the films surveyed offer perspectives from the ‘margins’, as it were, from people who live restricted lives within majority structures and find, by various means, ways of co-existing in frames more of their own making (even if temporary). In these terms, it might appear that Erase and Forget is a spectrum pole apart, a commentary from inside one version of that majority structure mentioned, and in this case arguably its apex, the ‘military-industrial complex.’ However, Gritz’s own experience of that machinery lie in closer proximity to the others than might first appear. The working-class son of a combat military family, with few employment options open to him, Gritz’s life (through his own experience and understanding of the workings of power) has turned an inherited class and economic marginalisation into a personal even philosophical one, and has led him to make his own forms of ‘home’, successfully or otherwise, in a variety of locations and scales, where the practice of a direct engagement with social need and aspiration has been as necessary as in the other cases.

Acknowledgements

My thoughts above emerge from many conversations, for Taskafa with John Berger, Gülen Güler and Bill McAllister; Estate with Lasse Johansson, David Roberts and Ruth Marie Tunkara; Erase and Forget with Michael Uwemedimo; Here for Life with Taina Galis, Therese Henningsen and Adrian Jackson. With gratitude to Gareth Evans for his invaluable contribution over many years to my thinking these things through.

Footnotes

1 Online Etymology Dictionary

2 A Man with Tousled Hair 176

3 Exterminate all the Brutes 2

4 Documents sourced by the author, 2006

5 Interview with author, 2003: “Soldier of Fortune puts out a special edition trying to show me as some kind of butt wipe. … [but the mission] was not my idea. I got a letter. Perot admits General Tighe called me to conduct a covert mission into Laos. They thought that because I was Westmoreland’s soldier, if I say there aren’t any, then there was closure on this issue.” See also Gritz’s testimony before the Senate Select Committee Testimony & Depositions, November 23rd, 1992: General Eugene Tighe, Director, DIA, requested H. Ross Perot sponsor a private effort to determine whether or not any U.S. POWs were left alive. “Perot called me to his EDS, Dallas office in April 1979. He instructed me accordingly: ‘I want you to go over there and see everyone you have to see, do all the things you need to do. You come back and tell me there aren’t any American prisoners left alive. I don’t believe it and I’m not interested in bones.’”

6 Cockburn, St. Clair 107

7 Reagan, Annual Republican Congressional Fundraising Dinner, 11 May 1988, USA

8 KLASTV

9 Interview with author, 2005

10 This notion of ‘historical secretion’ grew out of a conversation between Michael Uwemedimo, Josephine Mcdonagh and myself, 2005

11 Le Guin 284

References

Berger, John. “A Man with Tousled Hair,” The Shape of a Pocket. Vintage International, 2003.

Cockburn, Alexander and St. Clair, Jeffrey. Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. VERSO, 1998.

KLASTV. Channel 8 Broadcast. 9 June 2002, USA.