VOLUME

ISSUE 09

Mobilities

The 2021 issue is Mobilities.

The study of mobilities over the centuries – of peoples, cultures, ideas, ideologies – speaks to the integral nature of the human condition to be constantly on the move, to be moved. Nature and its constitutive environments were prime conditions for the mobility of peoples as communities. Subsequently, as humans organised themselves, commerce, ideologies, religions and education became key movers of peoples as individuals.

ISSUE 09

2020

Mobilities

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Essays

Exhibition

Conversation

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Viral Mobilities

Essays

On becoming stilled

Comic Purgatory

Re-imaginings: to look back and move on

Exhibition

Conversation

An abridged conversation in acts

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy Editor

Anmari Van Nieuwenhove

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Editorial Board

Professor Patrick Flores, University of the Philippines

Dr. Peter Hill, Artist and Adjunct Professor, RMIT University, Melbourne

Professor Janis Jeffries, Goldsmiths, University of London

Dr. Charles Merewether, Art Historian, Independent Researcher, Curator and Scholar

Manager

Sureni Salgadoe

Contributors

Felipe Cervera

Christine Checinska

Rhett D’Costa and Lesley Instone

Lóránd Hegyi

Ingo Niermann

Khim Ong

Bojana Piškur

Vinita Ramani

Sherman Sam

Silke Schmickl

Wei Leng Tay and Olivier Krischer

The Editors and Editorial Board thank all reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments and feedback to the contributors.

Introduction

Introduction: Viral Mobilities

By the time ISSUE 09 went to print, the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) had swept the world, bringing utter devastation to societies and economies. Unbound by any notion of nation-state, political ideology, belief or care, a virus vectorised communities and geographies infecting and affecting. As institutions around which communities had built and organised themselves since the 18th century, fumbled and crumbled, hope and ‘normal’ was scarce.

The anthropocenic revenge had arrived. As gods fell silent, politicians, community leaders and healthcare professionals scrambled to arrest the pillage. A new way of living, working and engaging had to be birthed as tacit lines between self/community, professional/personal and embodied/existential perforated rapidly giving way to anxiety. Redefining cultural norms and practices, communities quickly introduced new rituals in personal and social distancing: masking, isolating, avoiding and disinfecting. As instruments of care, they seemed antithetical to human socialisation (as evidenced by many who objected), yet it is very much part of the embodiment of the modern digital/virtual zone—distanced, isolated and disaffected. A stark realisation.

The pandemic became poignant to the core issue of this volume.

The study of mobilities over the centuries—of peoples, cultures, ideas, ideologies—spoke to the integral nature of the human condition to be constantly on the move, to be moved. Nature and its constitutive environments were prime conditions for the mobility of peoples as communities. Subsequently, as humans organised themselves, commerce, ideologies, religions and education became key movers of peoples as individuals. The human interest to discover, push and conquer one’s body and mind functions as a third condition of mobility. These three motivations anchored the manner in which concepts of migration and diaspora were historically understood as evidenced by discourses on mobilities steeped in continental philosophy and the social sciences proposing multiple paradigms such as Baudelaire’s flaneur (1863, 1964), Castells’ network society (1996); Simmel’s will to connect through financial circulation (1900, 2004); Bauman’s liquid modernity (1993); and Bourdieu’s field (1983); to cite a few, to appreciate and study mobility as an epistemological system. Amidst this, the modern world remains fraught with ‘normalised’ wars, ‘nationalised’ religions, ‘televised’ fears, ‘modern’ slaveries, ‘digital’ dreams and ‘technologised bodies’ compounded by heterotopic hyper-cities (defined by major airports and other transitory systems) remaining a main source of attraction to many—from pilgrims to refugees to corporate expatriates to the intrepid traveller. Writings by Urry (2007), Collier (2013) and others, point to the criticality of circulatory systems found in these hyper-cities such as London, Singapore, Hong Kong, New York, to allow multi-layered circulations to meet and coalesce, fostering an emergence of a new type of nation: a self-sustaining, ideologically pragmatic site of innovation and creativity and a place of the possible. Pandemics have remained in the margins of the evolution of modern society as advancements in public health and science kept them at bay. Just as 20th century health crises such as AIDS, SARS, MERS, etc. ravaged through hyper-cities arriving and departing through flight, so did COVID-19.

The beauty of society is its resilience. Despite the challenges, the world of ideas continues to remain viral and vital. The essays in this edition reflect this. From addressing politics, identities and self-migratory practices, writers explore mobilities through objects, temporality, embodiment, corporeality, aesthetics and through participatory practices—framing critique and appreciation of the multiple threads of movement. These perspectives form the basis on which one can ascertain the current station of contemporary society, not only through the lens of the present crisis but above, around and beyond it.

Essays

Mobility = Wandering = Wondering

“Today, we remain stuck in the present. The loss of a reliable historical perspective generates the contemporary feeling of living through unproductive, wasted time.” — 191']Boris Groys1

Mobility

Today as I write this, a global pandemic is unfolding. Mostly the pandemic is taking place for me online via information from all over the world. We know that virus is mobile and we, humans, its mule. That is a very straightforward idea of mobility. Hop a ride and travel round the world. There is also the other thought, the internet provides speedy access to knowledge and information, that is seeing without moving. But what can mobility mean to an artist? In a prosaic way as I have suggested: travelling, seeing, showing.

In today’s sense the idea (and possibly ideal) of mobility often serves artists engaged with notions of identity and politics. Francis Alys, the Belgian artist based in Mexico City, for instance, is a good exemplar of this particular mode of interrogation. Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing), 1987, was an action in which Alys pushed a block of ice around Mexico City, or The Green Line, 2004, in which he walked along part of the green line that demarcated the different powers that administered Jerusalem, dripping green paint along the way. It is a remake of his 1995 work, The Leak, in which he took a walk from his gallery in Sao Paolo, dripping paint, and leaving a trail of blue splatters as homage to Jackson Pollock. His work is clever, and in his actions, there is a poetry as well as a pointed politics. Changing or charging the Abstract Expressionist gesture into a political one. Or, in the case of the block of ice, an existential statement about labour. Alys’ works use motion but require the viewers to have a measure of global understanding or awareness.

From the point of our discussion, Alys’ is a very straight forward display of movement, motion, international travel, understanding, and thus mobility. However, I’m interested in another way to look at that notion. The one performed in painting through its materiality and history. Wander through any art gallery, and you find painted objects that belong to different eras, or even contemporary ones. Their singular reified nature may convey a sense of being “stuck” in their moment, yet, illogically even, they still speak to us in our present.

Can looking at a singular static object make us travel? What I want to explore is the notion that paintings tend to be far richer objects than they first appear. To demonstrate this, let us take journey through two paintings and an exhibition that may or may not be tangentially connected, outside of the fact that they are paintings. And just maybe that is enough. Before returning to Groy’s notion of wasting time in the present. For the moment, let’s call this trip (no pun) a travel through time, or maybe with time...

Wandering

Le Déjeneur sur L’herbe, 1863

Edouard Manet, Lunch on the grass (Le Déjeneur sur L’herbe), 1863

Oil on canvas, 208 x 265 cms

Collection of Paris, Musée d’Orsay, donation by Etienne Moreau-Nélaton in 1906

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay)/ Benoît Touchard / Mathieu Rabeau

It is well known that the composition of Edouard Manet’s 1863 masterwork Le Déjeneur sur L’herbe draws from Raphael and Giorgione or Titian. The painting depicts two dressed men picnicking alongside a naked woman in the countryside, in the background a semi-dressed lady bathes in a pond. At their side sits a basket and food. To be precise, the composition actually draws from Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving after Raphael’s The Judgement of Paris, 1510-20, and the young Titian’s, then thought to be the hand of his master Giorgione’s, Concert Champetre, 1509, which is located in the Louvre. The former provides the poses for the foreground trio, while the latter depicts clothed males with undressed females. In both cases it is the portrayal of a bacchanalian reverie in a rural setting. However, the modernist art historian Michael Fried, from which this analysis draws, also connected Manet’s early paintings with French and Flemish sources, touching on all the major European schools of painting and ending with a particular mode of French painting.2

Fried points out that Le Déjeneur is in the spirit of Antoine Watteau’s fête galante (courtship party). This category was created by the French academy to accommodate Watteau’s variations on the fête champêtre. That is the garden party or country feast populated by elegant guests, occasionally in fancy dress, which were popular in the 18th century French courts. This connection with Watteau’s fête was also noted by the critics of Manet’s era. In addition, Fried deduced that Watteau’s La Villageoise, which depicts a woman wading into shallow water with skirt upraised while glancing to the side, provided the pose for the bather in Le Déjeneur. In fact, when Manet’s painting was first exhibited in the Salon des Refusés in 1863, it was titled Le Bain (The Bath), and thus placing emphasis on the action in the background. A final connection is to Gustave Courbet’s, Young Women on the Banks of the Seine, 1856-57, having caused a scandal in the Salon of 1857 with its depiction of two women of loose morals—as was commonly accepted then, like those of Le Déjeneur. Fried points to the boat in the background as Manet’s “gratuitous quotation of Courbet’s rowboat,” which then connects the two paintings in his [Fried’s] eyes.3

Why even consider seemingly less direct quotations by French painters when the Italians provided such obvious points of reference? In “Manet’s Sources,” Fried argues that the idea of Manet we know is seen through the prism of Impressionism, that is, through the vision of the artists that came after, who were in fact inspired by the Frenchman. It is akin to our thinking of Cezanne through Picasso’s cubism. The point of connecting with Louis Le Nain (in Manet’s previous work, Old Musician, 1862) and Courbet is, for Fried, a sign of Manet’s commitment to their ideals of realism. This fact evades us given our Impressionist-coded outlook. Fried outlines a different zeitgeist: what he terms the “Generation of 1863,” comprising of Henri Fantin-Latour, James McNeill Whistler, and Alphonse Legros, as well as Manet.4 And in this, grasping the “pre-Impressionist meaning”5 of Manet’s paintings through his peers, instead of the ideas around gesture, roughness and spontaneity, qualities that are ever present in Manet’s painting. However, it is the notion of allusion and absorption of his subjects and compositions that Fried is interested in teasing out. In one sense it is a question of nationalism, identity and painting. “Which painters, ancient and modern,” writes Fried in 1967, “are authentically French and which are not? More generally, in what does the essence or natural genius of French painting consist? Does a body of painting in fact exist in which that essence or genius is completely realised? Has painting in France ever been truly national, or has it always fallen short of that ideal, however the ideal itself is understood?”6 These were the questions and thoughts posed by critics, historians and artists of the time. Fried, in Manet’s Sources, is interested in first a notion of Frenchness that critics at the time were espousing, and then of a universality. In this last point, I would add that in our terms today, we could say Manet brought a sense of “contemporaneity” (“modernity” would have been the phrase he would have used in his time) to his painting; he was very contemporary in his concerns to engage with the French painting of his era (such as Le Nain, Courbet).

Rather than rehearse the intellectual complexity posed by Fried’s analysis in terms of absorption,7 or even the visual complexity and ambition (and ensuring scandal) within Manet’s painting itself (comprising of all the genres: history, still life, portraiture, the nude, etc),8 it is the idea that this painting is not a sealed universe (of a picnic scene) in itself and belonging to the past.9 In rehearsing the complex matrix of sources to Le Déjeneur, as pointed out by Fried, I hope that not only a celestial sense of connectivity but also a feeling of time flowing through a singular object comes to the fore. What do I mean by this? Well, when we confront Manet’s masterpiece in the Musee D’Orsay we see it in the present. But within the painting, there lie references to 16th century Italian art, as well as an ambitious attempt at contemporary painting in 19th century France by way of past century of French masters.

Connections: Brice Marden, Boston, 1991

Another artist that connected with Manet, albeit more tangentially, is Brice Marden. It may seem strange to bring together an American renowned for his reductive monochromes with a French artwork rich with figurative allusions and pictorial complexity, but in 1991 Marden organised an exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Fine Art that included the Frenchman. This was part of their Connections series where artists were invited to intersperse their work with selections from the Museum’s collections. Boston is also the city where Marden studied as an undergraduate. In his introduction, Marden’s co-curator from the museum, Trevor Fairbrother, deduced that a “taste for the painterly and for the somber was probably reinforced by two large works by Edouard Manet that Marden studied in this museum during his student years in Boston.”10 The resulting show was akin to a mini-survey punctuated with paintings by Ensor and Gauguin among others as well as prints and drawings, etc., as well as objects from Marden’s personal collection such as Neolithic Chinese Jars and 20th century scrolls and textiles. In his review The New York Times critic, Michael Kimmelman compared the small black Marden situated near Manet’s The Execution of the Emperor Maximillian. He writes: “The lush surface of [Marden’s] Earth I echoes the rich blacks and grays that are to be found in the Manet. But the relationship between these works is more than formal. Mr. Marden suggests that the tragedy explicit in The Execution is somehow implicit in his abstractions. Works in the same gallery by Goya, Giacometti and Zurbaran similarly underscore the idea. And at the same time, they emphasise the figurative implications that Mr. Marden seems to hope a viewer will see in his spare designs.”11

Over the years, Zurbaran and Goya were also cited as inspirations, but a key influence not included in Connections: Brice Marden was Jasper Johns. His encaustic paintings in the 1960s depicted flat things in the world, such as flags, maps and targets. These representations could be perceived as self-referential: the painting of the flag is itself a flag, and a target is a target. For Marden they were also “maintaining the plane… [it is] this almost mythological illusion/non-illusion on the surface of the painting.”12 Marden’s response was to drain the imagery away and use wax to create large monochromatic ‘things’. These early works were made with a combination of wax, turpentine and oil paint applied with a palette knife. I say ‘things’ of his earliest works as they were painted from the top and edge to edge, while at the bottom the paint was allowed to drip. These dribbles act in reinforcing each painting’s physicality, while ‘being’ traces of their hand-made nature. In addition, their smooth wax surfaces imbue the rectangular canvases with a sensuous object-like quality. Illusion dissipates right there on the surface, as if it had been pushed down and melted away. Marden refers to these bottom edges as “open”: working on the ‘plane’ so to speak.

“Open” is perhaps the operative term in relation to his oeuvre and approach, despite their early resemblance to minimal art—the movement of his generation. An early Marden’s reductive materiality is only really an anchor for its evocative qualities. It is through colour as Fairbrother and Kimmelman accurately noted, where his art opens out to the world. In the case of Earth I, its blackness draws in the emotive drama of Manet. Likewise, it is colour that brings up ‘subject matter’ for many paintings of that period; it is usually a sense or feel for landscape or nature. However, it is the spatial quality we find in our landscapes rather than a specific place—instead of a depiction, it is a feeling. For instance, the monochromatic Nebraska, 1966, is a “homage”: its colour, green-grey, found while driving through the US state: “viridian, plus this, plus that, plus that.”13 While the Grove Group series takes its palette from olives trees in Greece, Marden had said: “I don’t try to replicate nature. I just try to work from the information that nature gives me.”14 And this information is colour.

Marden’s paintings of that period, Earth I, Nebraska, at first inferred an end to painting, as if they were the last paintings in a Modernist end game. Yet, we know now that they are not the last, instead they recall other monochromes, reductive painters and endgames: Reinhardt, Malevich, Newman, Yves Klein, Rauschenberg (whose monochromes, despite their jest-ful gestures, were nonetheless single coloured), Richter, even Stephen Prina. On the other hand, their wax surface conjoins with artists like Johns and Beuys. Instead of time moving backwards that Le Déjeneur performs, there is a moving sideways as well as circularity sense as monochromes echo and recall each other in our present. Maybe it is like jazz, where certain rhythm or standards can be performed and improvised on by different musicians, each time echoing the structure but each time arriving some place else, possibly some place new.

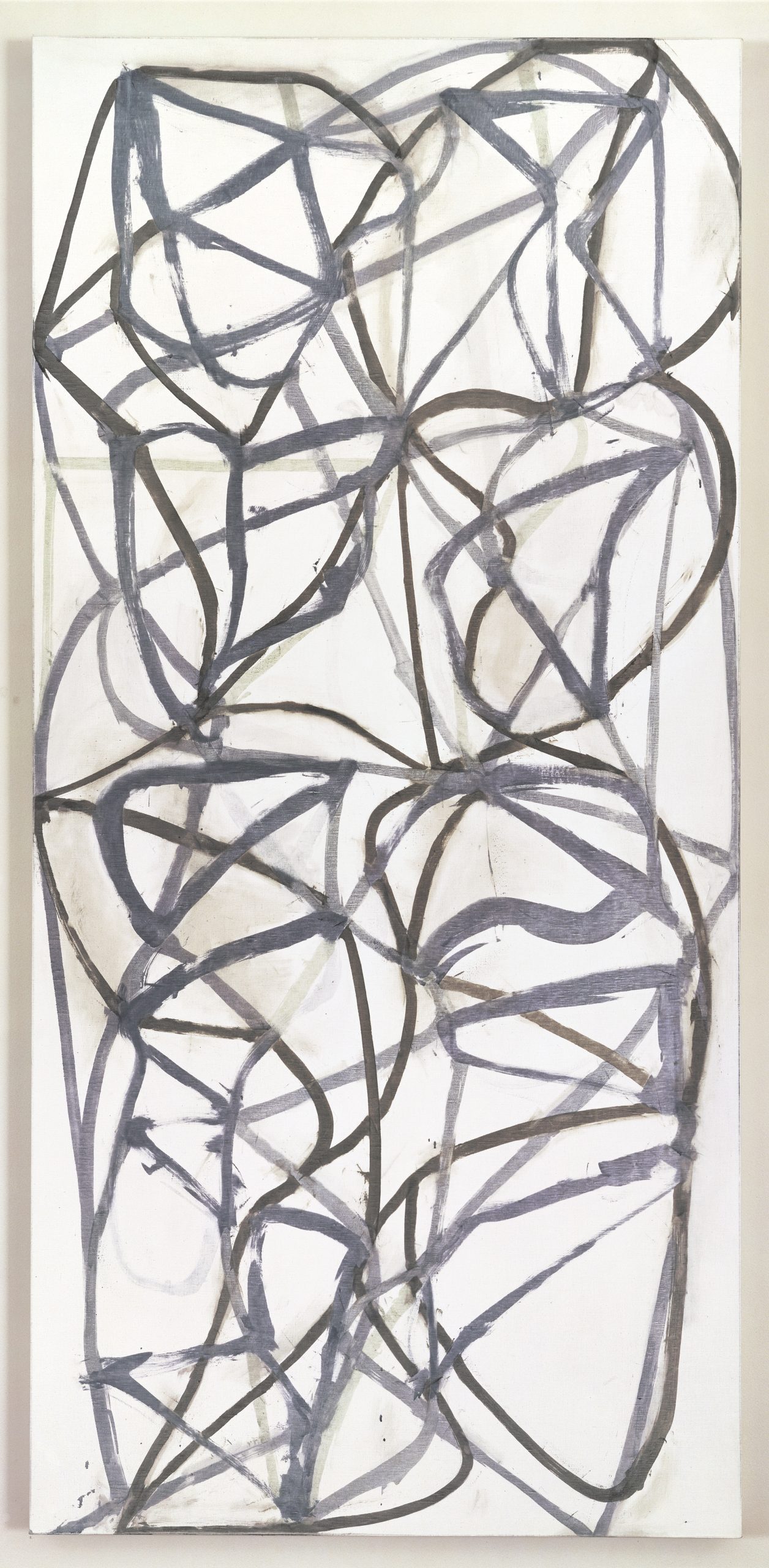

By the time of the Boston show, Marden was already turning away from the monochrome. Gestures and visual structures inspired by Chinese calligraphy and poetry had begun to appear on those lush surfaces. Instead of smooth and sullen allusion, atmosphere brought about from painting, erasure and re-painting came to the fore. In a sense his method of applying pigments in veils, layers and unveiling were still consistent, but now he was using oil paint, and placing emphasis on the drawing—leaving more traces, and in the end unveiling more than veiling. These works from the late 80s connected as much with the weblike skeins of Jackson Pollock’s drips as they do with Eastern calligraphy. Diagrammed Couplet #1, 1988-89, for instance, used the structure of Chinese poems, right to left, up to down, while pieces like Cold Mountain I, 1988-89, with their stuttering architectonic lines conjure—at least to me—the rawness of some cave paintings, even without animals or handprints. The elegant roughness of his touch suggests mountain crags or misty Chinese landscapes.

Brice Marden, Diagrammed Couplet #2 , 1988–89

Oil on linen, 213.36 x 101.6 cms

© 1989 Brice Marden / Artist Rights Society (ARS),

New York Photograph by Zindman/Fremont © 1989

If Manet’s Le Dejeuner walks backward in time with direct references from 15th century Giorgione and Raphael before swinging back round to meet 17th century Watteau, Le Nain, and most of all Courbet in the 19th, Marden’s paintings in this exhibition allude to different epochs. First, in the earlier works there is the timelessness of nature. Here the idea of the Modernist monochrome provides another notion of timelessness in its endless series and variation. In the later works, Pollock, representing another kind of modernism in the 20th, merges with Chinese calligraphy. Unlike Manet’s painting, there is a sense a circular timelessness to Marden’s endeavour.

Rosebud, 1983

Terry Myers: When I brought a group of students to your studio in Bridgehampton last summer, they were moved by your suggestion that, in the end, maybe your paintings weren’t so important.

Mary Heilmann: Well, it is a kind of deep concept, the idea that the conversation the paintings cause is more relevant than the actual ‘masterpiece’. I think of a painting a sign or a word that you put out in a conversation, and then people answer it. I mean, that’s really why I did it, all the way from the beginning.15

That idea of conversation also exists between artworks as well. Say the one between Manet with Le Nain and Courbet, etc., but also more obviously in the Connections exhibition with Marden next to Manet and Goya. Unlike the points of reference exuded by Manet or even Marden, Mary Heilmann’s work seems to spring from a more intimate place. We could say that her expression comes through adopting a more conversational tone. Trained as a ceramicist by Peter Voulkos on the west coast, who was renowned for his innovative abstract expressionist ceramics, Heilmannn eventually moved on to study sculpture with William T. Wiley, in a time when artists like Eva Hesse, Lynda Benglis, Ken Price, and her friend, Bruce Nauman, were redefining the idea of form. Of this period she says, “When I was finishing school, some things that started to come out of New York were really important for me: Dick Bellamy’s Arp to Artschwager show at Noah Goldowski Gallery; Lucy Lippard’s Eccentric Abstraction show at Fishchbach; the Primary Structures show at the Jewish Museum… I knew that my work related to this kind of thinking, and as soon as I finished school I headed for New York.”16 They were seminal shows that redefined sculpture, more specifically defining American sculpture.

Yet, soon after arriving in the city, Heilmann switched from sculpture to painting. However, notions of sculptural structure and playful, languid paint (the sort you find on pottery) still underpin her work. “First,” she says, “they are objects then they are pictures of something…”17 What are they pictures of? Like the American abstractionist Thomas Nozkowski, each work is drawn from an experience in her life—a “backstory” in her words. Though Nozkowski abstracts and distills, allowing the narrative to recede, Heilmann uses titles to keep her sources close: Our Lady of the Flowers, The Kiss, The Blues for Miles, Good Vibrations (for David), The Black Door, The Big Wave. Those are her points of departure: at arrival, her paintings exude a joyful ease, whose charm later however belies their depth of sophistication. For me, the easy attitude she takes to moving paint could be compared to the way glazes are applied to clay, like a kind of surface decoration. Nothing signifies their casualness more than when she allows paint to seep into the edges of her tape leaving her lines and shapes with uneven, serrated edges. This is not intended to suggest that there is no rigour to Heilmann’s work, rather the opposite. You feel that the paint is very close to the top, if not on the surface. This is not the same way that Marden plays with the plane. For me, it is Matisse that her work channels. Intense colour and space opened by colour but one that is demarcated by line or edge; those are the very operations by which both the Frenchman‘s and the Californian‘s paintings perform. However, where a Matisse seems cool and analytical, Heilmann is all hot and personal. The New York critic, John Yau, observes that Heilmann was one of the first artists to “absorb the lessons of Pop artists, particularly their allusions to popular culture” and it is the “synthesis of pop colour and geometric abstraction in palpably layered or optically juxtaposed compositions” that create “the absence of fixity.”18

A 1983 painting, Rosebud, is partly inspired by the martyrdom of St. Sebastian: it is an creamy all white field covered with 17 red splotches spread unevenly across. Although paintings of the Saint date from earlier, it seems to me that the dramatic ones come from the Renaissance and after. However, the only sign of this passion is the dripping red paint. Passion is certainly the theme; it is also inspired by a breakup.19 In appearance, however, Heilmann’s painting could be a leftfield pattern painting (a 70s West Coast, anti-formalist painting movement) or an oddball piece of post-painterly abstraction. That is, it is both cool and hot.

Mary Heilmann, Rosebud, 1983

Oil on canvas, 152.4 x 106.68 cms

©Mary Heilmann

Photo: Christopher Burke Studio

Courtesy of the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth

Its title, Rosebud, might refer to the MacGuffin in the Orson Welles’ film Citizen Kane, 1941. Rosebud was the childhood sled that symbolises the Orson Welles’ film character’s lost innocence.20 Perhaps roses blooming might be what those haptic red swirls suggest. Or is it symbolic of loss? Bleeding and weeping. And, of course, they could also be roses budding. In her impressionistic, note-like response to this particular Heilmann, the painter Jutta Koether writes that it is “[the] most emotional painting of all. Creating the crying one...ornaments and wounds. An emotional field, painted as pouring sentimentality, true sentiments, that stick around, making the painting. Making it through to an optimism, eventually. Yet is heart-crushingly pop…”21 Rosebud is, in a sense, reductive but it is also expressionistic. It’s reductive nature acts like a Marden monochrome, but in terms of evocation, as Koether correctly notes, they may be more cultural than they are artistic. It is far from the passion of a tortured saint, and far from away the Renaissance. However, in Citizen Kane, or in “blossomings” either bloody or in nature, there is a hint of the cinematic—that is a 20th century phenomenon.

Do we really see a painting in its time? No, we may be conscious of its era but we meet it in our present. That is, in a practical sense, our eyes/vision touch paint applied by a hand nearly 200 years ago. So, from the 21st century, we are, in a sense, travelling across the centuries by viewing a 19th century object with its references to the 16th and 18th centuries, as well as richly alluding to painting of its own time. Or even a late 20th century work monochrome cycling through the history of that genre.

Wondering… or coming off the wall

In his conclusory remarks on Alys, quoted in my epigraph, Boris Groys describes the present as repetitive and non-historical. It has “lost its past and future...and [is] infinitely repeated”—in other words a sort of existential Groundhog Day. Groys is talking about contemporary life, but it seems prescient in regard to ‘contemporary art’ which seems to inhabit a continuous present: one place, one time, one issue, all the time. Yes, I’m stereotyping, but speaking as a painter, I sense a shying away from painting at the moment. Perhaps its history is too storied, too full or even completed, and thus of no use value to an infinitely repeated, non-historical present that may want to reduce painting to a mere rectangle on the wall.

Rather as I’ve tried to show, it is far more complex than at first glance. It is easy to see them in the present, but the tableau could also be an opening, window, door, crack...The richness of the form, as I’ve been trying to demonstrate with these different examples and moments in time, offers another kind of mobility. It allows the mind to wander. Each stroke of paint inadvertently connects with history, connects with other paintings. Time travel while standing right where you are: looking at a painting. It is not quite like sitting at the computer screen where information on the world floods to your fingertips. Rather, it requires the mind to engage in another way...to wander. Then to wonder! And that is the exact pleasure of painting.

Now to go back in time again: a final thought. Do you know that painting came off the wall? Painting actually began on the wall—think cave painting and then church painting ala Giotto. When it came off, it was called a tableau or easel painting. The word “easel” is etymologically derived from the German word for donkey. It is the painter’s mule so to speak. Given the origins of painting, easel painting allowed artists to be on the road. There is some irony to this, as at first it was the painters that had to be mobile. They travelled to the cave or the church to make their murals. Then they became studio artists, when easel and canvases allowed the paintings instead to become mobile. When paint was made industrially and sold in tubes, another idea of mobility came about. That is when painters were more able to move outside and make plein-air paintings. We don’t actually use the words “easel painting” much anymore, perhaps it is because easels themselves are less popular. When critics were discussing Abstract Expressionism, easel painting was discussed as something they were going to surpass, as if the artists were trying to put painting back on the wall again.

(With thanks to my first readers: Marcus Verhagen and Clive Hodgson)

Footnotes

1 Groys, “How to do Time with Art,” Francis Alys [exh. cat.] 191

2 Fried, Manet’s Modernism. The book is based on his doctoral thesis, “Manet’s Sources: Aspects of His Art, 1859-65” published in Artforum 7. It had some notoriety as it was the only instance in which Artforum dedicated a whole issue to one article. Manet’s Modernism republishes “Manet’s Sources” without change. Instead Fried correctly dedicates the follow chapters to develop, criticise and deepen his arguments.

3 Ibid. 68.

4 Ibid. see chapter 3, The Generation of 1863

5 Ibid. 6-7

6 Ibid. 75

7 In the period between writing “Manet’s Sources,” 1967, and Manet’s Modernism, 1996, Fried’s research led him to drawing out ideas of absorption which surpasses his original interest in Frenchness and universality. The two books, Aborption and Theatricality and Courbet’s Realism, set the ground work for his understanding of Manet’s ‘facingness’.

8 For a more complex analysis of the painting, see Læssøe 195-220

9 For a sense of the scandal the painting caused in this time, see Bourdieu 14-18

10 Fairbrother Intro.

11 Kimmelman 35

12 What painting is all about,” Youtube, at 1:36 min/2:48 min.

13 Marden: “I had written colour notes. You know, like, viridian, plus this, plus that, plus that. So I’m starting with a vague idea about Nebraska, these greens of Nebraska or whatever feelings I had driving through the landscape, and then I’m turning it into a very specific thing called a painting. It’s not a representation of Nebraska, but it wouldn’t be called Nebraska if Nebraska wasn’t a big help. It was meant to be some sort of an homage.” Brice Marden. Nebraska. 1966.

14 Brice Marden on finding inspiration in olive groves.

15 Myers,”Heil Mary” 74

16 The All Night Movie 38

17 “Mary Heilmann in Fantasy” at 17.56 min.

18 Yau 49.

19 Yablonsky “The Composer”

20 Bradshaw ”Citizen Kane”

21 The All Night Movie 86

References

Bradshaw, Peter. ”Citizen Kane and the meaning of Rosebud.” The Guardian, 25 April 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/apr/25/citizen-kane-rosebud

Bourdieu, Pierre. Manet: A Symbolic Revolution. Cambridge, 2017; Paris, 2013, pp.14-18.

Fairbrother, J. Trevor, Marden, Brice. Brice Marden, Boston: a “Connections” project at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1991.

Fried, Michael. Aborption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot, Chicago, 1980.

Fried, Michael. Courbet’s Realism. Chicago, 1990.

Fried, Michael. Manet’s Modernism: or, The Face of Painting in the 1860s. University of Chicago, 1996.

Groys, Boris. “How to do Time with Art,” Francis Alys [exh. cat.]. London, 2010.

Heilmannn, Mary, et al. The All Night Movie. Offizin, 1999.

Kimmelman, Michael. “Art View: Brice Marden reveals his connections.” New York Times, 14 April, 1991.

Læssøe, Rolf. “Édouard Manet’s “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe” as a Veiled Allegory of Painting.” Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 26, No. 51 (2005), pp. 195-220, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e8f5/6d12629b3b6bfcc1fc72e6608146f4402f33.pdf

“Manet’s Sources: Aspects of His Art, 1859-65.” Artforum 7, Mar 1967, pp. 28-82.

Marden, Brice. “Brice Marden on finding inspiration in olive groves.” SFMOMA, (n.d.) https://www.sfmoma.org/watch/brice-marden-on-finding-inspiration-in-olive-groves/

Marden, Brice. Interview by Gary Garrels. “‘Brice Marden. Nebraska. 1966.” MoMA. https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/207/2714]

Marden, Brice. “What painting is all about.” Youtube, uploaded by SFMOMA, 11 Feb 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5S4jOOrBf5U

“Mary Heilmannn in ‘Fantasy’: Art in the 21st Century.” Art21, video, 14 October 2009, https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s5/mary-Heilmannn-in-fantasy-segment/

Myers, Terry. “Heil Mary.” Interview with Mary Heilmann, in Modern Painters, April 2007, p 74.

Smith, Roberta. ”The Paintbrush in the Digital Age.” The New York Times, 11 December 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/12/arts/design/the-forever-now-a-survey-of-contemporary-painting-at-moma.html

Yablonsky, Linda. “The Composer: Mary Heilmann’s Rhythmic Abstractions Find Their Place in the Sun.” Art News, Mar 2016, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/the-composer-mary-Heilmannns-rhymthic-abstractions-find-their-place-in-the-sun-5959/

Yau, John. “Save the Last Dance for Me.” Mary Heilmannn: Color and Passion. Hatje Cantz, 1998.

Essays

The undeniable and unmissable appealing and intriguing mystery of art—whenever and wherever it appears—in all of its forms and in all of its negation of previous forms, is basically and inseparably connected with its challenging, deep, sometimes shocking and destabilising power, which effects the life. The seemingly “useless”1 work of art, as Hannah Arendt puts it, in its extremity and alienness, in its autonomy and self-determination, is changing our feelings and intellectual orientation: it effects our life and relation to the time, to the place where we live, to the others, we live with.

The artist’s engagement and obsession is to create this unique entity, this extremely concentrated and multilayered specific “micro-universe” which owns the capacity and competence of involving unlimited references, evocations, memories and perspectives of human experience in a suggestive and irresistible shape of solid internal coherence. The message of the artwork thus has its legitimacy from this coherence. It suggests a possible but not the only possible understanding of the things and happenings around us. There is always an uncertainty which destabilises our orientation but at the same time opens us up toward different perspectives and surprising connections between fields of experiences.

***

“In the case of art works, reification is more than mere transformation; it is transfiguration, a veritable metamorphosis in which it is as though the course of nature which wills that all fire burn to ashes is reverted and even dust can burst into flames. Works of art are thought things...” —Hannah Arendt2

In her book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt describes a work of art as a phenomenon in which the permanence and durability of the world, its very stability, is revealed with a clarity and transparence that can be found nowhere else. This function of the artwork, which otherwise – in the practical, tangible sense – is “useless”, consists in the fact that in it, the durability of the world appears in an absolutely clear form, so suggestive and brilliant that other perspectives of the perception of the world, other visions of reality, are opened up. “Because of their outstanding permanence, works of art are the most intensely worldly of all tangible things; their durability is almost untouched by the corroding effect of natural processes, since they are not subject to the use of living creatures... In this permanence, the very stability of the human artifice, which, being inhabited and used by mortals, can never be absolute, achieves a representation of its own. Nowhere else does the sheer durability of the world appear in such purity and clarity, nowhere else, therefore, does this thing-world reveal itself so spectacularly as the non-mortal home for mortal beings. It is as though worldly stability had become transparent in the permanence of art, so that a premonition of immortality, not the immortality of the soul or of life, but of something immortal achieved by mortal hands, has become tangibly present...”3

There are two particularly important points here, which illuminate the specific significance of the artwork for human beings and reveal the essence of the central metaphor of Islands Never Found,4 namely the island. On the one hand, Hannah Arendt speaks of the possibility of experiencing, in and through the work of art, the durability of the world, the “worldly stability” that is impossible to perceive anywhere in the “thing-world”. This means that the work of art offers a unique, specific opportunity to perceive an aspect of existence directly, with the senses. The specific entity of the artwork consists in its ability to communicate an inherently clear, transparent and poetically effective vision of the world’s permanence, which is otherwise hidden by the thing-world.

On the other hand, Hannah Arendt talks about the effect of the artwork on human beings. The immediate, moving experience of the durability of the world perceived through its transparent revelation in the work of art, the experience of a “premonition of immortality” as it were, opens up a perspective, a horizon, that allows human beings to perceive and understand their entire situation, their realities, in a different way. This cathartic experience, the comprehension of alternatives communicated through the aesthetic entity of the artwork, the ability to experience immortality metaphorically, one might say, to envision an imagined existence in immortality, is, in turn, related to the special status of the work of art. Perceived from this perspective, the artwork reifies a radical imaginary or fictional perfection of existence in which the alternatives of immortal life— which are practically impossible in the thing-world—appear to be possible.

This poetic, imaginary, fictional perfection relates to the alternative of the uncompromising—and, in the thing-world, practically impossible—essence of the world, its fundamental—and, in principle, unchangeable—immutable permanence and durability, even though individual mortals must die. Inherent in the experience of this “premonition of immortality” through a work of art is the interiorisation of metaphoric perfection, the metaphor of an imaginary, fictional homeland of unlimited – perfectly realised – life.

This second aspect of the special status of the work of art as a communicator of possible perspectives for thought, as a terrain upon which essential experiences can be perceived in transparent, clear forms – which is impossible in the thing-world – is related to the most important function of an artwork, namely its capacity to unveil essential realities, the “durability of the world.” It is only in this clarity and transparence that mortal human beings can find a “non-mortal home,” in which things “achieved by mortal hands” survive beyond their creators. All the values that are embodied in the works of mortal human beings are incorporated in this “non-mortal home.”

The specific capacity of a work of art to unveil essential realities and thereby offer a glimpse of the perspectives of creative perfection, a transparent revelation of the fundamental permanence of the world, enables human beings to see and contextualise their existence on a broader, more complex, more intensive, higher level through the perception of the artwork. The metaphor of the “non-mortal home” is a reference to this higher level. Although individual human beings must die, they comprehend—through the perception of an artwork—the “durability of the world” in full clarity and transparence, and precisely this experience enables them, despite their mortality, to find a “non-mortal home.” In other words, the perception of the “durability of the world”—in the experience of art—enables us to grasp the idea of a “non-mortal home” in which the basic values manifested in things created by “mortal hands” survive beyond individual human mortality. These values are part of the permanence of the world.

Thus, by giving human beings the chance to perceive the permanence of the world with a clearness and transparency impossible in the thing-world, and thereby offering a “premonition of immortality,” a work of art becomes an imaginary, rare terrain, a fictional island where immortality is a possibility; the very independence of this island from the pragmatic rules of usefulness and practical, functional realities permits a radicalness of clarity and transparence in which the “durability of the world” can be perceived in its purest form.

In this connection, immortality is a metaphor for the perfection of creativity and of work, for the non-transience of things made by human beings. Immortality means an unlimited capacity of creation, an uncompromising radicalness of all possible poetic constructions of thought, an unrestricted creativity and freedom of the imagination. A work of art discloses a “premonition of immortality,” which allows us to consider the existence and the creative work of human beings from a different, higher perspective. This intimation of a possible higher level, of a different, special way of viewing things, is the message communicated by a work of art, and as a result it stands, like an island, distant from the usual “thing-world.” On this island, with its “premonition of immortality,” the fictional, imaginary alternatives unfold: the improbable figures of unlimited, radical fantasy, the intelligible constructions of poetic effectivity, and they unfold with a radicalness, clarity and uncompromisingness that is not possible anywhere else. Such islands are strange lands where improbabilities find a natural home, because, having been liberated from the mandatory laws of necessity in the thing-world, they can manifest and develop imaginary constructions and alternative ideas in complete freedom and without compromise.

In his astute analysis of Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the picture, Raymond Bellour describes Deleuze’s perception of the figure in the paintings of Francis Bacon as “the figure that is improbability itself.” Raymond Bellour points out that Deleuze saw parallels between the writings of Marcel Proust and the paintings of Francis Bacon, in the sense that both of them rejected the “figurative, illustrative or narrative“ function of literature or of painting and wanted to give sensual form to “thought-of or seen probabilities” through the radical independence of the text or of the picture. As Deleuze, speaking of Proust, claimed: “He himself spoke of truths that are written with the help of figures.”5 Paradoxically, it is precisely through the specifically created figure, which “is improbability itself,” that the artist can convey these “thought-of or seen probabilities.” The concept of improbability relates to the special status of the work of art, which is not bound by the laws of necessity in the world of things, nor by the illustrative, narrative functions of everyday speech, but can reify thought-of alternatives and the visions of wild imagination with unlimited radicalness and uncompromisingness.

Barthélémy Toguo, Road to exile, 2008

Wooden boat, bundles of fabrics, bottles

220 x 260 x 135 cm

Courtesy MAM Mario Mauroner Contemporary Vienna + Salzburg

Danica Dakić, La Grande Galerie, 2004

C-print on aluminium

100 x 128 cm

Edition 8 +2

© Danica Dakic / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn - SACK, Seoul, 2020

Photo: © Egbert Trogemann / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn-SACK, Seoul, 2020

The work of art is a specific domain where fundamental anthropological realities become graspable with radical intensity through the extremity of the figures of improbability. The work of art is an island of improbabilities, which, through the unrestricted radicalness of imagination, through independence from the pragmatic, limited, purpose-oriented functions of the world of things, through the freedom of alternative thinking – gives expression to highly important, fundamental and elementary experiences of inevitable realities with immediacy and power, making them, as Hannah Arendt writes, “tangibly present, to shine and to be seen, to sound and to be heard, to speak and to be read.”6

This radicalness, arising out of uncompromising, unrestricted, intensive concentration on the direct communication of basic realities, creates the feeling of a creativity, an inexhaustible power, that can withstand the mortality of human beings. The optimistic, romantic metaphor of the “non-mortal home” refers to the competence and ability of art to reify basic values—which are not clearly manifested in the thing-world, which in the practical processes of the organisation of life and purpose-oriented work are not transparent and graspable in any concentrated form – in the extreme forms of art and to make them perceivable. The metaphor of the “non-mortal home” suggests no religious visions of eternity, but rather gives us the hope that not everything will be lost when we die, that we will not disappear into oblivion, that we need not surrender to the desolation of limitations and intellectual constriction.

This metaphor is one of activism, based on the work of mortal human beings, and reinforces human immanence; its central focus is on the preservation of the values human beings create. The work of art offers a domain where these values can be preserved, where they can live on. It also means that everything we have to lose is the result of human creativity, the work of “mortal hands.” For this reason, Hannah Arendt emphasises the importance of human immanence in the immortality metaphor: “It is as though worldly stability had become transparent in the permanence of art, so that a premonition of immortality, not the immortality of the soul or of life, but of something immortal achieved by mortal hands, has become tangibly present...”7

This rich, complex metaphor—which reinforces human immanence, confirms the creative perfection of work and suggests an alternative way of viewing the world—refers at the same time to the specific entity of the artwork as a terrain of revelation of fundamental experiences and to the effect of the artwork as a communicator of alternative ways of viewing the world and thereby of a new self-recognition. In this connection, there is a parallel to Nietzsche’s extremely complex metaphor of “life”. To Nietzsche, the metaphor of “life” relates to a radical perfection and also to an alternative way of viewing the world. As Christoph Menke describes: “This programme of a transformation of practice aims at a different way of doing things. It is different from the model of action. ‘Aesthetic transformation of practice’ means: breaking the power of the concept of action (and all other related concepts: purpose, reasons, intention, capability, self-confidence etc.) with respect to being active. The doctrine of artists is: One can be active in other ways than in the purpose-oriented, self-confident exercise of practical capability. Nietzsche’s term for describing this other way of engaging in activity, other than action, is ‘life’. Being active in the way that artists are active does not mean performing actions, it means ‘living’.”8

The metaphor ‘life’ suggests radically and uncompromisingly realised perfection that arises not in the context of practical, purpose-oriented action, but in artistic “doing”. This emphasises the special status and the specific entity of art as a terrain where a suggestive, unlimited perfection that is graspable with the senses can be realised. This radical perfection, this independence from the rules and causalities of the purpose-oriented actions of the thing-world, is only possible on the terrain of art, in the artist’s “doing”. “In artistic perfection, in the artist’s Dionysian ‘doing’, on the other hand, we do not have a subject performing an action to realise a known and wanted purpose, but rather someone acting in the grip of intoxication to realise— himself: ‘The human being in this condition transforms things until they reflect his power, until they are reflections of his perfection.’ The ‘aesthetic doing and seeing’ consequently leads to a transformation, a perfection of things. But this change that it precipitates is not brought about in the artistic activity: it is not the purpose of this activity. Artistic activity is not based or oriented on any purpose at all. Artistic activity is the ‘reflection’ or ‘communication’ of the state the artist is in when he does what he does.... When Nietzsche describes it as ‘intoxication’, he means, as in the birth of tragedy, a state of ‘heightened power and fullness,’ which he here again refers to as ‘Dionysian’.”9

Like Nietzsche, Arendt too, emphasises the basic difference between the purpose-oriented action of a subject in the thing-world and purposeless artistic activity, and points out the qualitative difference between useful objects and “useless” works of art.10 The lack of a purpose is related to a claim to perfection, to unlimited, uncompromising creation, since purpose-oriented action is necessarily limited, being restricted to the fulfilment of a previously known, deliberate, specific function. The purposelessness of artistic activity positions the artwork outside of the thing-world and makes radicalness, concentration and the unlimited heightening of creative powers possible. Nietzsche, on the other hand, speaks of “powers” as of an activity outside of consciousness; powers are unconscious. This is what he means by intoxication: intoxication is a state in which the subject’s powers are so greatly intensified that they are beyond the subject’s conscious control. Or conversely: the unleashing of powers in intoxication consists in their transcending the aggregate state of self-conscious capacity that they preserve in purpose-oriented action. “Therefore, a human being in a Dionysian state of heightened powers is defined by an essential inability: ‘the inability not to react (similarly to certain hysterics, who assume a role at the slightest provocation)’: the inability to act as the power to be compelled to react aesthetically, to be compelled to express oneself.”11

Kimsooja, Bottari Truck – Migrateurs, 2007

Single Channel Video Projection, silent, 10:00, loop, performed in Paris

Commissioned by Musée d’Art Contemporain du Val-De-Marne (MAC/VAL)

Still Photo by Thierry Depagne. Courtesy Kimsooja Studio and KEWENIG, Berlin

Richard Long, Mediterranean Arc, 2008

Stones

730 cm radius

Courtesy the artist and Tucci Russo Studio per l’Arte Contemporanea, Torre Pellice

Photo: Archivio fotografico Tucci Russo, Torre Pellice

This inability to act within the context of the thing-world creates the specific sensitivity and radicalness, autonomy and un-restrictedness that is needed in order to be active outside the context of purpose-oriented action: to strive for improbabilities—one might say to create without restrictions—to have alternative ideas that do not accept any of the boundaries set by purpose-oriented goals. In this specific state, on the terrain of art, on the island of the artist, a hyper-intensive artistic process of perfecting takes place, without limitations and without restricting purposes or goals: be they practical, political, didactic or moral. On the island of art, this radical perfecting process becomes palpable, and this intensive experience offers a glimpse of alternative perspectives, of higher horizons, thereby revealing, in Nietzsche’s sense, a different “life” or, in the words of Hannah Arendt, a “premonition of immortality.” On the terrain of art, on the island of the artist, there is a hint of something that in everyday life, in the purpose-oriented thing-world, cannot be seen or experienced with such immediacy, with such radicalness and intensity. Here we are given an unrestrainedly radical, unlimitedly intensive, highly concentrated, unembellished, unfiltered experience of fundamental realities. That is why Nietzsche calls this fundamental encounter, this radical, unlimited, elementary experience simply “life”, a strong metaphor, as we see, for perfection or perfecting, and he suggests that everything else is not real life, or at least is only limited action based on certain purpose-oriented goals. In artistic activity, perfecting acquires a radical intensity that cannot be described in the terms of purpose-oriented action.

In this connection, Christoph Menke believes: “The essential step in an aesthetic transformation of practice consists therefore in learning, from the artist’s example, to make a conceptual decision: in learning, in the field of activity, to distinguish between action and life. The first result of this newly acquired ability to discriminate is a new description of the field of practicality. Anyone who has learned from artists that it is possible to be active without being involved in action can see how practicality spreads into life everywhere, downwards as well as upwards... ‘Life, one concludes from this new aesthetic description, is both the lowest (in descriptive terms, most elementary) and the highest (in normative terms, most sophisticated) concept of a philosophy of practicality: ‘life’ is the destiny of movement and goodness.”12

This real ‘life’ reveals itself through the heightened “powers” of intoxication, through the radicalness, extremity and total un-restrictedness of artistic doing. Radical imagination, liberation from any sort of purpose-oriented, practical, limited goals, the development of forms and narratives of improbabilities, lead to an intensification of fundamental experiences. In this respect, the contemporary artists Gilbert & George say: “If you want to be a speaking artist, you have to be totally crazy, MAD, extreme. Otherwise it doesn’t work. You have to be a complete outsider, totally alone. If you are part of something, nothing will happen.”13 Craziness, madness, extremity, radicalness are elements of the intoxication that enables artists to place themselves, in a sense, outside the laws of normality, outside the pragmatic thing-world, outside purpose-oriented action.

Consequently, the artist achieves a special status that offers the possibility—even if it is not always accepted everywhere, without conditions, without argument, by everyone, by the entire community, by the cultural environment —of uninhibited, indiscriminate, radical, unrestrictedly autonomous language and creative form. This free, concentrated, autonomous language focuses on what is important, on the essence of things, even if this appears in the seemingly most trivial, imperceptible, unobtrusive banalities and their observation. The expression “speaking artist” used by Gilbert & George refers to this radicalness of language, of speaking out, of the fundamental vocation of the artist to say something important, fundamental, essential. Nietzsche’s metaphor of “life”, Hannah Arendt’s “durability of the world,” and Gilbert & George’s “speaking artist,” all imply that the ability and competence to create a highly concentrated, radically intensified, uninhibited and uncompromising, unfiltered state of extreme sensitivity are inherent in artistic activity. If an artist is involved in any kind of action, if he is “part of something.” If he is not a complete outsider, he cannot achieve this state of exceptional autonomy and thus will be not be capable of being a “speaking artist.” It is only this outsider position that makes it possible for artists to have the radicalness and extreme sensitivity with which to reveal a new entity through what they do.

But the artist’s outsider position also creates loneliness, isolation, apartness from pragmatic, comprehensible, purpose-oriented actions; precisely this radicalness and hyper-intensity, this uncontrollable madness, this extremity, un-restrictedness and exceptional autonomy create the island, which becomes not only the land of perfection, the special, peculiar terrain of intensified experience of fundamental realities, the field of unlimited sensitivity, but also an island of alienation and apartness, of loneliness and mistrust, of imprisonment and doubt.

Apartness and strangeness, exterritoriality and extremity, intensity and radicalness—in short, to “march to a different drummer”—characterise the adventure, which, according to Georg Simmel, has a basic similarity with the work of art. “It is precisely when continuity with life is disregarded on principle in this way, or rather, when it does not even have to be disregarded—when something is already there that is alien, untouchable, marching to a different drummer—that we speak of adventure. It lacks that reciprocal penetration with the adjoining parts of life through which life becomes whole. It is like an island in life which determines its beginning and its end by means of its own formative powers, and not, like a piece of a continent, together with those of what is on either side of it. [...] For it is the nature of a work of art that it cuts a piece out of the endless, ongoing flow of perceivable comprehensibility or experience, takes it out of its context, and gives it a self-sufficient form, as if determined and held together by some internal centre. That a part of existence is woven into its uninterruptedness, is nevertheless experienced as a whole, as a complete unit – this is the form that a work of art and an adventure have in common.”14

Siobhán Hapaska, Playa de los Intranquilos, 2004

Fibreglass, two pack acrylic paint, sand, palm tree trunks, synthetic foliage, coconuts, nylon, plastic and glass

Dimensions variable

Edition of 3

Courtesy the artist and Kerlin Gallery

Adventure: another complex, poetically dense, powerful, effective metaphor for the ability of an artist to create, out of an inner formative power, an extremely intense and autonomous form of existence “outside the usual continuity of this life.”15 With the ‘adventure’ metaphor, Georg Simmel describes the special status of artistic activity, one might say the specific entity of the work of art, which, through its provocative independence, through its eccentricity in “marching to a different drummer,” through its radical “detachment from the meshes and links of the purposes in life,” is able to centre itself “in a meaning that exists of itself.”16 Such extremity, unattachedness, exterritoriality insists on staying “outside the usual continuity of this life,” refuses to become involved in the pragmatic causalities of the thing-world, removes itself from the logic of life and is thereby capable of capturing perfection and radical intensity. Through their uncompromising independence and “detachment from the meshes and links,” the adventure and the artwork “are perceived, in all the one-sidedness and coincidence of their substance, as if all of life were somehow concentrated and completed in each of them. And this seems to happen not to a lesser degree, but more perfectly, because the artwork stands altogether outside of life as a reality, the adventure is something totally separate from the uninterrupted, connected process of life in which each element is interwoven with its neighbors. Precisely because the artwork and the adventure stand apart from life..., the one and the other are analogous to the totality of life itself.”17 That is the reason for the enigmatic, indisputable, powerful effect of a work of art, namely the intense experience of a feeling of wholeness, the dramatic encounter with the hyper-intensive, concentrated totality of life, which can be grasped precisely in this form of extreme strangeness, of unusual, eccentric separateness. On this exterritorial island of anomalies, in this strange land of improbabilities, where “that reciprocal penetration with the adjoining parts of life”18 is missing, we experience a feeling of extremely intensive wholeness and perfection of the various areas of life and experience. Exterritoriality, detachment, separation from the rational contexts of life, or—to use Nietzsche’s words—artistic doing, rather than practical, purpose-oriented action, or, as Hannah Arendt describes it, the uselessness of the artwork and its special status in the thing-world, or what Gilbert & George call extremity, craziness, uncompromising outsiderness and radical loneliness as the price of the freedom and independence of “speaking artists”: all these metaphors refer to the specific ability of art to create an alternative reality that is more real than the given, graspable realities in non-artistic areas of organised life.

The artist, lonely in his final decisions, alone on his island, incapable of ever knowing whether it is really his own island, his suitable, prepared, living terrain, nor even – to take it further – whether it exists anywhere at all, seeks ways and means of grasping the intensification of the feeling of experiencing something fundamental and complete, in other words, of achieving perfection. The artist, just like his kinsman, the adventurer, “finds a central feeling about life that leads through the eccentricity of the adventure and, precisely in the great distance between the accidental, externally given happenings of the adventure and the centre of existence that pulls everything together and gives it meaning, produces a new, meaningful necessity of his life.”19 It is this “meaningful necessity of life” that reveals itself on the artist’s strange, distant island, often very far from us, often never found or found too late, and nevertheless reachable for everyone.

(Translation by Beverley Blaschke, Vienna)

Footnotes

1 Hannah Arendt 168

2 Ibid. 168

3 Arendt 167 f.

4 Curated by Hegyi and Katerina Koskina, the exhibition was presented at the State Museum of Contemporary Art Thessaloniki, Palazzo Ducale, Genova, 2010

5 Bellour 15

6 168

7 168

8 Menke 114

9 Ibid. 112

10 Arendt 167. Cf Arendt: “Because of their outstanding permanence, works of art are the most intensely worldly of all tangible things; their durability is almost untouched by the corroding effect of natural processes, since they are not subject to the use of living creatures, a use which, indeed, far from actualising their own inherent purpose—as the purpose of a chair is actualised when it is sat upon—can only destroy them. Thus their durability is of a higher order than that which all things need in order to exist at all; it can attain permanence throughout the ages.”

11 Menke 113

12 Ibid. 114

13 Gilbert & George 94

14 Simmel 41

15 Ibid. 39

16 Ibid. 40

17 Ibid. 41

18 Ibid. 41

19 Ibid. 43

References

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press Chicago 1958. 2nd edition 1998. [German version: Vita activa oder Vom tätigen Leben (translated by the author) Piper Verlag, Munich 1967].

Bellour, Raymond. “Das Bild des Denkens: Kunst oder Philosophie, oder darüber Hinaus.” Deleuze und die Künste, edited by Peter Gente and Peter Weibel, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2007, pp.15.

Bellour, Raymond. “The Image of Thought: Art or Philosophy, or Beyond.” Deleuze and the Arts, edited by Peter Gente and Peter Weibel, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2007.

“Gilbert & George: Interview with Martin Gayford.” Exhibition catalogue Gilbert & George, Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1997-1998.

Menke, Christoph. Kraft Ein Grundbegriff ästhetischer Anthropologie (Kraft - A Basic Concept of Aesthetic Anthropology). Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2008.

Simmel, Georg. “Das Abenteuer.” Simmel, Georg: Das Abenteuer und andere Essays (The Adventure and other essays), edited by Christian Schärf. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2010.

Essays

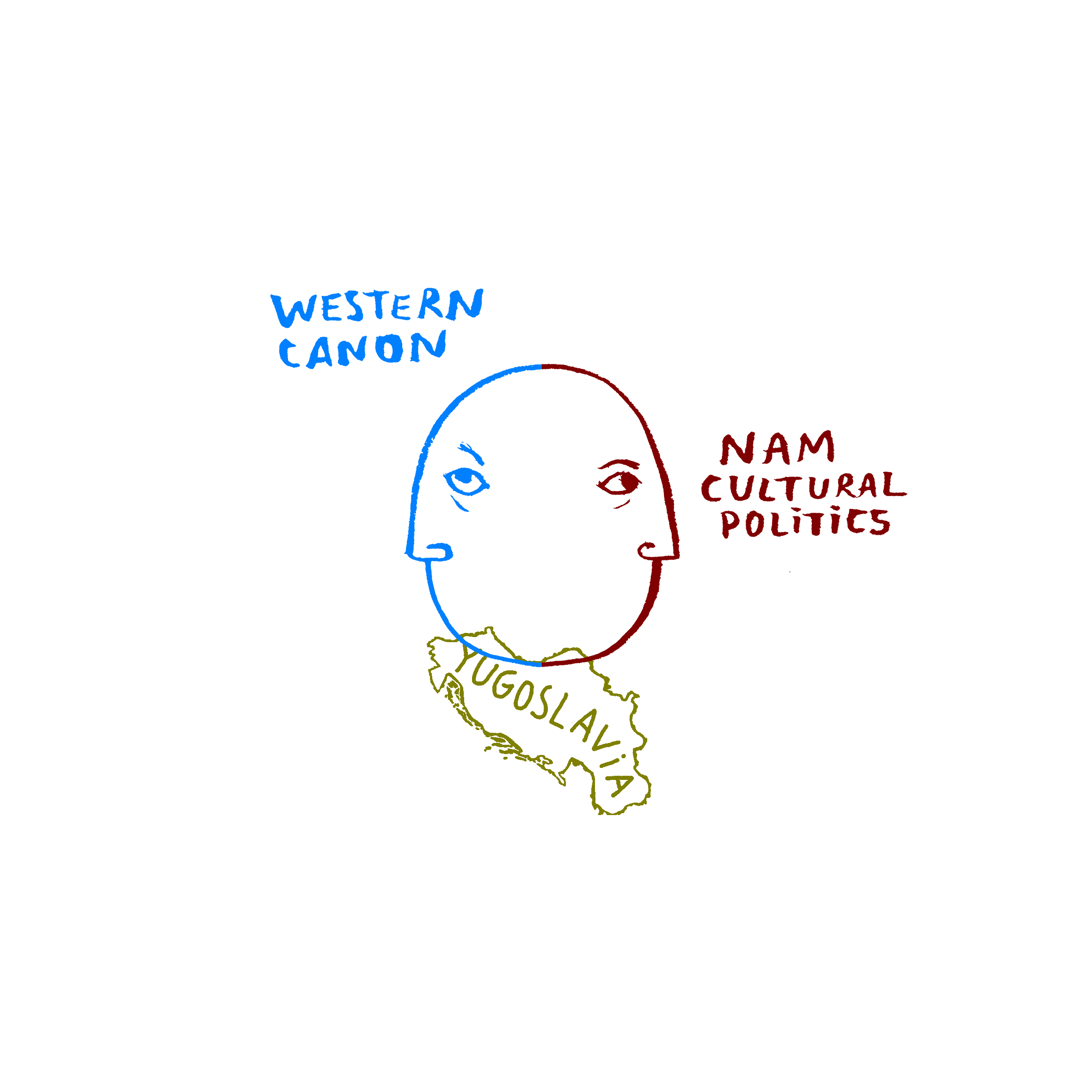

In recent years there has been a renewed interest in the ’idea’ of Yugoslavia,1 not only in our region, but also globally. This interest has to do primarily with specific Yugoslav socialism as well as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) of which Yugoslavia was a key member. The reasons are many: disillusions in the current global world order, especially rapid neo-liberal globalisation which has created huge problems; inequality, the rise of new forms of dependency (economic, political); the rise of right-wing politics and fascisms; and so on.

The NAM represented, at least until the 1980s, a significant “rupture” on the global level—an attempt at an alternative mondialisation, and a desire to create a more just, equal and peaceful world order. Yugoslavia was a special case in this constellation, it helped to bring non-colonial Europe into the grouping. Unlike many colonial narratives, Yugoslavia had never asserted itself as a nation or culture that worked to ‘civilise’ others.2 Instead, it cultivated and maintained the notion of itself as the culture/nation that aimed to help others establish a position in a role that had yet to be created and clearly defined (the ‘older brother’ paradigm, which is also problematic from today’s perspective). Yugoslavia’s socialist, anti-imperial revolution had a lot in common with anti-colonial ones which made the Yugoslav case of emancipation particularly significant. Being one of the key members in the NAM, Yugoslavia supported global anti-colonial struggles3 not only politically but also economically and culturally.

Art and culture played an important role in the NAM, even though comparatively little is known about this today. The reason is that after the Second World War, the main orientation in arts and culture in many non-aligned (decolonised, newly independent) countries as well as in Yugoslavia was the one following the Western epistemic canon.4 The other non-western ‘story’ comprised of various “provincialised modernisms,”5 and heterogeneous expressions propagated ideas that were often in line with similar issues that non-alignment addressed. Such ideas were, for example, the questioning of cultural imperialism, restitution and epistemic colonialism. NAM’s cultural politics from the beginning specifically encouraged cultural diversity and cultural hybridity. Western (European) cultural heritage was to be understood in terms of “juxtaposition”6; this heritage would be interwoven with and into the living culture of the colonised, and would not simply be repeated under new (political) circumstances. For this reason, a “cross-national appreciation for cultural heritages” and a local-to-local approach was extremely important.

Jugoslavija (Yugoslavia) booklet from the series

Non-aligned and the Non-alignment

published by Rad, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1975

Private archives

Yugoslavia might be a good case-study for this cultural dilemma. On one hand, Western canons were widely accepted in the art circles and on the other, non-Western ones were politically stimulated through various cultural policies connected to the NAM. However, they were stimulated without a deeper understanding of what “other” modernisms really meant, as it is clear from reports, texts and concrete cases such as exhibitions and other museological contexts of that era. But in order to better understand this specific phenomenon we first need to go at least a hundred years back.

“In 1963 all Africa must be free!”7

In the late 1920s, there was already a growing fascination among Yugoslavia’s cultural circles with faraway places. However, few Yugoslavs travelled to exotic places, largely because Yugoslavia was not a colonial country and as such had no colonial experience. There were exceptions; there were Yugoslavs studying in France who showed a particular interest in Africa; many of them belonged to the surrealist circles, including Rastko Petrović, an avant-garde writer, poet and diplomat who travelled to Western Africa in 1929. His book Africa8 is a record of that journey. The book was in some ways a typical product of the era, written from the perspective of a white European male, based on pre-conceived colonial knowledge and stereotypes about Africa. Petrović nevertheless attempted to answer the question what it meant to be an “European Other” in Africa; or to put it in a somewhat larger frame, what it meant at the time to be a European “from a margin of European modernity.” Another important Paris encounter unfolded in 1934, when Petar Guberina, a PhD student of linguistics at the Sorbonne, met Aimé Césaire.9 Guberina invited Césaire to his native city Šibenik that same year, and it was there that Césaire started writing his famous epic poem Notebook of a Return to the Native Land,10 which was one of the first expressions of the concept of negritude. Not surprisingly, the preface was written by Guberina. Another figure in that circle was Léopold Senghor, who later became President of Senegal and travelled to Yugoslavia on an official state visit in 1975. In his speech at the First International Congress of Black Writers in Paris in 1956,11 he pointed out: “Cultural liberation is the condition sine qua non of political liberation.” A few years later Guberina published a book, Following the Black African Culture, in which many of Césaire’s and Senghor’s thoughts on culture resonated. In what sounded much like Senghor’s Paris speech, he wrote: “Black cultural workers, although there were few, have manifested a multifaceted function of culture and used it as a powerful weapon against colonisation. Cultural workers have become political workers and vice versa.”12

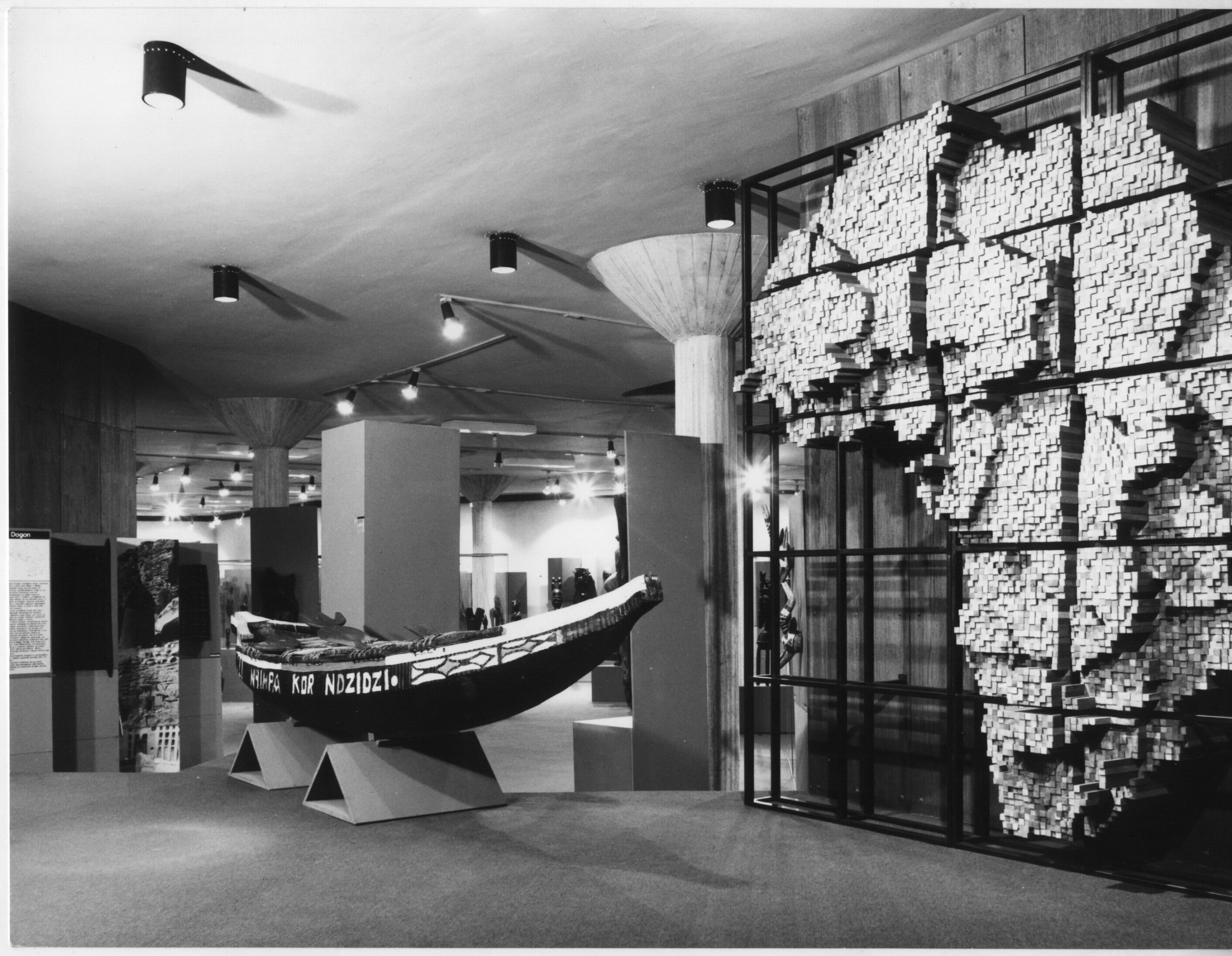

The permanent display of the Museum of African Art (MAA)—

the Veda and Dr. Zdravko Pečar Collection, 1977

Photographed by Branko Kosić. Photo courtesy of the Museum of African Art

—the Veda and Dr. Zdravko Pečar Collection, Belgrade (MAA)

The MAA permanent display, concept by Jelena Aranđjelović Lazić,

design by Saveta and Slobodan Mašić, 1977

MAA Photo Archives

It was the 1960s in particular, that saw the rebirth of a specific travel literature about “exotic places,” the most prominent example of which was the work of Oskar Davičo—not surprisingly another surrealist writer and politician who had visited Western Africa to prepare for a meeting of the NAM. He wrote a book about the journey called Black on White, in which he analysed African post-colonial societies at the time. Davičo, a very different observer than Petrović, did not want to be seen as a white man in Africa. Moreover, he was even ashamed of his whiteness, saying that if he could change the colour of his skin he would have done so without regret: “Yes, I am white, that is all the passers-by see. If only I could wear my country’s history digest on my lapel!”13

A year later, travel journalist Dušan Savnik began his book Black Continent with an exclamation: “In 1963 all Africa must be free!”14

To make the Third World a place from which to speak.15

Already at the 1956 UNESCO16 conference in New Delhi, a great importance was put on “dissemination of art works of contemporary artists.”17 Interestingly, the focus of such cooperation was between “the peoples and nations of the Orient and the Occident.”18

A few years later, the 1964 report of Heads of State participating at the second Non-Aligned Conference in Cairo considered cultural equality one of the important principles of the NAM, at the same time recognising that many cultures were suppressed under colonial domination and that international understanding required a rehabilitation of these cultures. In the Colombo Resolution in 1976, emphasis was placed on restitution; the members requested restitution of works of art to the countries from which they had been expropriated.19 And at the conference in Havana in 1979, Josip Broz Tito spoke of the resolute struggle for decolonisation in the field of culture. The Havana Declaration also emphasised cooperation among the non-aligned and developing countries, as well as: “...better cultural acquaintance; and the exchange and enrichment of national cultures for the benefit of over-all social development and progress, for full national emancipation and independence, for greater understanding among the peoples and for peace in the world.”20 The Delhi Declaration in 1983 focused more specifically on cultural heritage and its preservation, as well as on cooperation in culture between the NAM members.

In Yugoslavia, a special committee was established after the Second World War called the Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, which arranged exhibitions outside Yugoslavia’s borders and was chaired by the surrealist writer and artist Marko Ristić. Cultural conventions and programs of cultural cooperation included not only Western and Eastern Europe, but also non-aligned countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. These exchanges touched on all levels of cultural production. Cultural cooperation between the non-aligned countries was based on conventions on culture and programs of cultural collaboration.

Yugoslavia, for example, has signed agreements with 56 non-aligned members and observers. In addition, between the 1960s and 1980s many new biennials opened throughout the non-aligned world signifying a different kind of cultural exchange: Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana; Triennale-India in New Delhi; Coltejer Art Biennial in Colombia; International Art Biennale in Valparaíso; Asian Art Biennale Bangladesh in Chile; Biennial of Arab Art in Baghdad, Iraq; Havana Biennial in Cuba and others.

Yugoslavia propagated its ideology and culture globally on the basis of the formula: specific modernism(s) (based on Western canons) + Yugoslav socialism21 = emancipatory politics. It was at the same time an articulation of an idea, and an attempt to show the world how it is possible to direct one’s own modernisation processes.

The NAM’s cultural politics were intertwined into Yugoslav cultural politics but in reality those other modernisms and art expressions were never of significant consideration in Yugoslav society nor were they part of the museological deliberations. There existed exceptions in architecture and urban planning but also with the establishment of some new collections, institutions and exhibitions.

“Art of the World” in Yugoslavia

As mentioned already in the first chapter, Yugoslavia had special relations with the newly independent countries in Africa and Asia from the late 1950s. President Tito often travelled to those countries on so called “Journeys of Peace.” A particularly significant one was his visit to Western African countries on the Galeb (Seagull) boat in 1961, not as a conqueror, but to support the independence of post-colonial states. These travels consequently acquired a strong economic dimension and created new spheres of interest and exchange among countries of the NAM. Intense economic collaboration at first included Yugoslav construction companies working on projects in Africa and the Middle East—companies that had sprung up as a consequence of the rapid urbanisation of Yugoslavia after the Second World War. Probably the largest of them was the Energoprojekt22 construction company from Belgrade that operated in 50 non-aligned countries, designing and building infrastructure (hydropower plants, irrigation systems, and electricity networks) and buildings (mostly conference halls, office buildings, hotels, etc). Constructing companies provided everything “from design to construction,” including architecture and urban planning. Such examples, as mentioned, were projects in various African and Arab non-aligned countries, like Energoprojekt’s Lagos International Trade Fair (1974-77), where architects combined specific (Yugoslav) modernism with tropical modernism and the local contexts.

Dubravka Sekulić’s project on Energoprojekt. Exhibition view

Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned. Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2019

Photo: Dejan Habicht, Moderna galerija

Dubravka Sekulić’s project on Energoprojekt. Exhibition view

Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned. Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2019

Photo: Dejan Habicht, Moderna galerija

Map (Asia) of Yugoslavia’s international collaboration in culture with developing countries

Researcher: Teja Merhar, map design: Djordje Balmazović

Project for the Southern Constellations: Poetics of the Non-Aligned

Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2019

Cover of the catalogue for the travelling exhibition contemporary yugoslav prints, 1976

Moderna galerija Archives

Exhibition view. Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned. Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2019

Left to right: the works of Rafiqun Nabi (Bangladesh), Cho Geumsoo (North Korea),

Elba Jimenez (Nicaragua), and Agnes Clara Ovando Sans De Franck (Bolivia)

Photo: Dejan Habicht, Moderna galerija