VOLUME

ISSUE 02

Echo: The Poetics of Translation

Of the theme Echo:

Walter Benjamin once compared translation to hearing an echo in a forest. Such a metaphor for the act of translation suggests the sonic if not oral dimension of language and reminds us of the way in which there is a space between the original and its repetition. Translation then is a rich terrain of exploration for the arts.

ISSUE 02

2013

Echo: The Poetics of Translation

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Essays

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Echo

Essays

When the Eye Frames Red with Trinh Minh-ha

Calendars (2020-2096): Heman Chong in Conversation

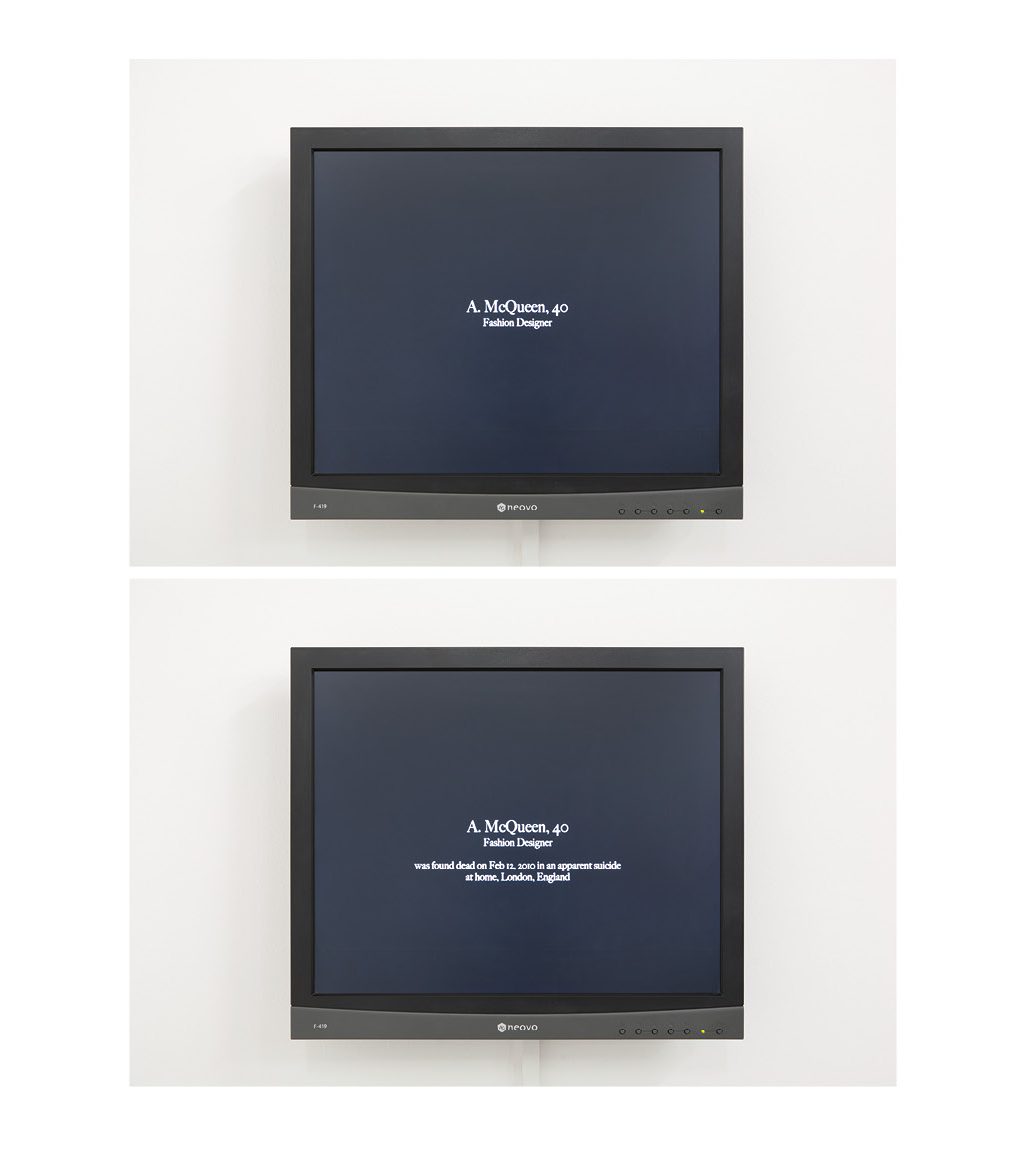

On Dying Alone

From Plato’s Cave to the Bat Cave

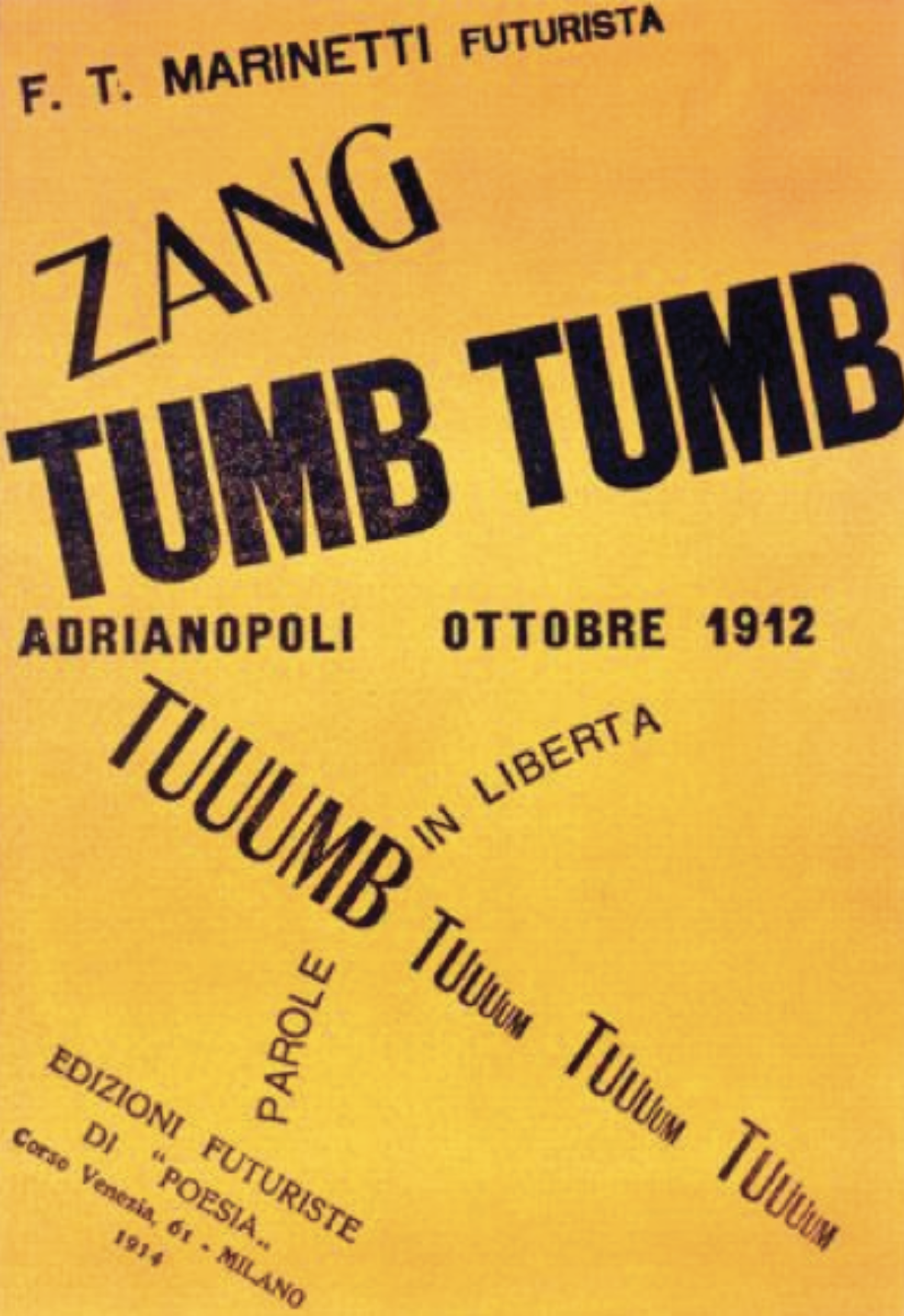

Echo as a Musical Metaphor

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor-in-Chief

Dr Charles Merewether

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy-Editor

Lisa Li

Advisor

Milenko Prvacki

Senior Fellow

LASALLE College of the Arts

Manager

Olivia Cain

Contributors

Ahmad Mashadi

Akira Mizuta Lippit

Alex Mitchell

Darren Moore

Jecheol Park

Joanne Leow

Lauren Reid

Michael Lee

Miguel Escobar Varela Richard Streitmatter-Tran

Introduction

Introduction: Echo

The second volume of ISSUE commences with a provocation that Walter Benjamin compared translation to hearing an echo in a forest; and that the echo is not the original sound, and the copy not the original.1 To investigate this, we need to resuscitate the flailing nymph Echo pinning for the love of Narcissus, and one has to return to the primordial scene: the sighting.

In this volume, we have echoed two interviews, revisiting them to gain new insights, new reverberances: Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s “When the Eyes Frames Red” 1999 interview and Heman Chong’s “Calendars (2020-2096)” 2011 interview. Both have been selected to serve as parasites for the primordial scene. Trinh’s work paves a perspectival way to seeing and framing while Chong’s provides a critical rendition of time’s own entrapment within the condition of structure.

The ensuing essays by artists, filmmakers, academics and musicians represent a plethora of viewpoints, starting points and end points responding in their own to the echoes. They are intended to serve as counterpoints to the para-sites thereby providing a new rendition to an age-old conundrum regarding the real and original.

Footnotes

1 Introductory statement by renowned art historian, Dr. Charles Merewether at the international art residency, Tropical Lab 2013: LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore.

Essays

When the Eye Frames Red with Trinh Minh-ha

Lippit

I want to begin by thanking you for agreeing to sit for this interview. It’s perhaps worth noting that this interview is destined, at least in the first instance, for a Japanese audience. There has been a vibrant interest in your films and written work in Japan, where you have recently spent some time, so perhaps we can touch upon those experiences and your reception there a little later.

It is in some ways an extremely difficult task to approach you for an interview. The conventions of this medium assume some notion of a constant or discernable identity, an interviewee whose essential features are either already known or can be known. In the case of Trinh T. Minh-ha, one recognises a filmmaker and a scholar, but also an artist of many shades, a perpetual traveler, and a person whose own history in the world is marked by the epistemic shifts that characterise this century and its thought. Looking back on the various interviews collected in Framer Framed, I’m struck by the sheer diversity of subjects that you speak of, but also by the sometimes anxious ways in which the interviewer tries, at times, to situate you within established traditions of experimental filmmaking, the critique of anthropology and conventional documentary, ethnography, poetics, post-colonial thought, feminist thought and activity and so forth. I’ll try to resist the temptation to identify, as it were, a fixed dwelling and try instead to follow the nomadic qualities of your expansive work.

Since many of your previous interviews speak to your cultural politics and positions vis-à-vis the subject of alterity, I thought we might approach this conversation from the vantage of your films, which represent, in my opinion, absolutely discrete and distinct pieces of work, which are nonetheless bound by a very particular spirit or desire. So, perhaps to begin with this notion of a project, how do you define your film project—if you accept the notion of a project—and how does your film work fit into your broader artistic and intellectual projects?

Trinh

When I work on a film, I am drawn very intensely to the world of images and sounds. On a basic level, such a state of creative availability and of active receptivity is in itself a “project.” But the making of a film also opens up many doors to other means of creativity. It sharpens the edge between, let’s say, writing for a book and writing for a film—a difference one constantly faces when words are part of the film fabric. Not only does the use of language differ markedly from one medium to another, but working with storytelling, poetry and everyday speech in cinema also makes me aware of music in ways I never thought of before. If a poem is an invisible painting, as Chinese artists put it, then a film can be all at once visible poetry, musical painting and pictorial music. The spaces between image, sound and text remain spaces of generative multiplicity, in which the function of each is not to serve nor to rule over the other, but to expose, in their tight interactions, each other’s limit. What I cannot avoid experiencing at certain moments of the process is both the different strengths and limits of these tools of creativity. So it is in working constantly with these limits and with the circumstances that define them that I advance, quite blindly, actually. Even though in discussions, it does seem as if all my projects are very lucidly thought out, this comes in the making process, not before it. Most of the time I jump into a project blindly, and this is how boundaries are also displaced.

Lippit

So you see the production of a film as something that opens up a space for writing, thinking, and learning, even as you are creating the work itself?

Trinh

Yes, very strongly. There’s a whole web of activities involved in and triggered by the making of cinematic images. I have no such thing as a preconceived idea that I want to visualise or illustrate through film. It doesn’t happen that way; it’s more likely through an encounter—with a person, with a group of people, with an event, or with a current of energy that is sparked by a specific situation.

Lippit

Your body of films suggests a certain consistency, an idea not of any totality, but of a shared quality. When thinking in the abstract about your films, they seem to offer a shape, to have and take shape, yet when one looks at the films individually, they are in many ways radically different. There persists, however, a common desire or spirit that motivates them. One motif that appears strongly in all your work involves an aesthetic or politics of travel. Another is the notion of encounter and portraiture. A portraiture that is not always of people or places but sometimes of relations to places, producing a sense in which the viewer finds herself or himself the subject of a portrait—as if the spectator is being watched.

I am interested in this dual sense of absolutely discrete projects with completely separate foci and emphases on the one hand, and the persistence of a communal space that works in your films on the other. I have noticed that interviewers often try to identify you within very specific communities and it seems impossible to do so. There is, it seems, something fundamentally nomadic about your work both in its geographical momentum but also in its intellectual or creative capacity to wander, as it were, and move—

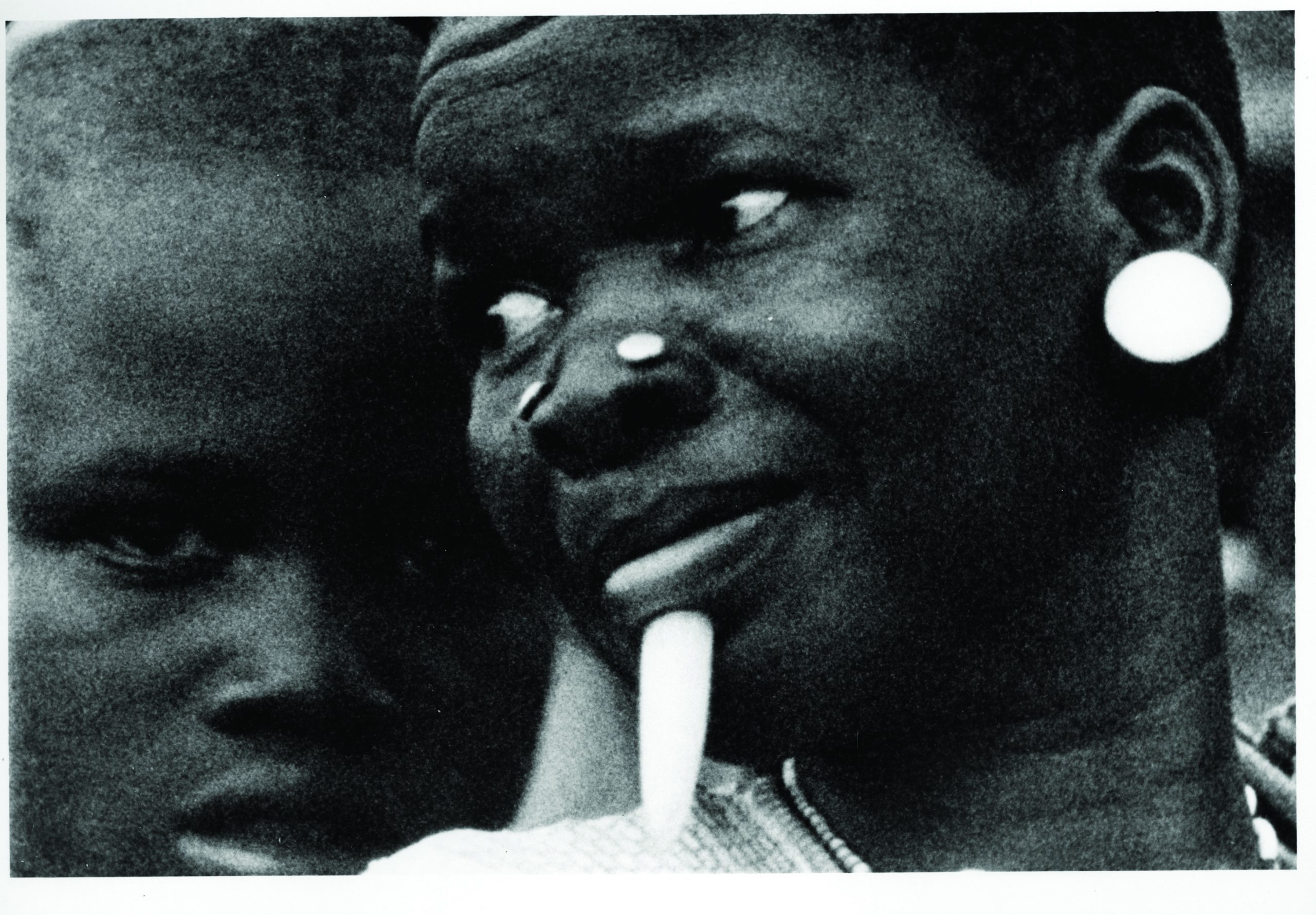

1, 2 Stills from Naked Spaces by Trinh T. Minh-ha, Courtesy Moongift Films.

Trinh

Perhaps something that seems recognisable in my work and can only be realised intuitively with each film, is this tendency in pushing the limits, to lead the work, just when its structure emerges, to the very edge where its potential to return to nothing also becomes tangible. Whatever takes shape does not do so simply in order to address form. In that sense, nothing really takes shape. By going towards things while letting them come to me in the mutually transformative process of filmmaking, I am not merely “giving form.” Taking shape is not a moment of arrival, and the question is not that of bringing something vague into visibility. Rather, the coming into shape is always a way to address the fact that there is no shape. Form is here an instance of formlessness, and vice-versa.

So when you talk about this sense of traveling, of wandering, and of not fitting comfortably in one group, it’s not so much something that constitutes an agenda on my part as something rather intuitive that corresponds to the way I live, to the skills of survival I’ve had to develop, and to my own sense of identity. I’m not at all interested in giving form to the formless, which is often what many creators reach for. Rather, I’m taken in by the creative process through which the form attained acutely speaks to the fragile and infinite reality of the world of forms—or, of living and dying.

How to incorporate that sense of the infinite in film is most exciting, even though we know that we always need a beginning and an ending, and that making a film is already to stop the flow or to offer a form. But rather than reaching a point of completion where form closes down on form, a closure can act simultaneously as an opening when it addresses the impossibility of framing reality in its subtle mobility. This is certainly one way of looking at what happens with all of my films.

The other aspect which you mentioned, which I love very much, is that, yes, there is a tendency to see the two films I shot in Africa as being alike and sometimes they are even scheduled to be screened one after the other in the same program slot. This is a terrible mistake, for Reassemblage and Naked Spaces need to be viewed as far apart from one another as possible, if the spectator’s creative and critical ability is to be solicited. Such a programming decision, detrimental to the reception of the films, tells us how people continue to see films predominantly in terms of subject matter. Yet how the two films are realised and how they physically affect the viewer are radically different. As I mentioned earlier, each encounter is so utterly bound to the elements that define it, that for me, it is impossible to reproduce, identically, what has been made at different moments of one’s itinerary, and with different peoples, circumstances and locations. The specificity of each encounter would dictate a different move for each film. In other words, each film has its own . . . field of energies.

Lippit

Yes, a vitality. It is surprising to think of Reassemblage and Naked Spaces as similar films. Do you feel that sometimes because the subject matter can be so powerful in your work that it interferes or disrupts other elements in the work? The subject matter you select is often very powerful.

Trinh

I’m very glad it comes out that way for you. There’s always a tendency to think that because I don’t come into a project with an idea in mind or with a preconceived political agenda, the content is of little account, which is not at all the case. I feel very strongly about the subject matter of each of the films—again, not as something that precedes but something that comes with the making of these films. In fact, people bewildered by the freedom with which my films are structured often react by saying, “Well then this film could have been made anywhere.” And I would have to say “No,” because each film generates its own bodyscape—as related to specific places, movements, events and peoples—which cannot be reproduced elsewhere.

But yes, I would agree that if the subject matter comes out strongly, then what we call structure, form, or even process, become less noticeable. Not because they are in any way less important, but because when everything clicks together in a film, it’s no longer possible to speak of form and content as separate entities. This reminds me of the other dimension, which you touched on earlier, namely, that the subject who films is always caught in the process of relating—or of making and re-presenting—and is not to be found outside that process. All of my films are actually attempts to bring out that process with and within the image. Because of the very tight “always-in-relation-to” situation, it is also difficult to simply indulge in the subject matter, as if it pre-exists out there, waiting to be retrieved “as it is.” There should always be some kind of a split somewhere that compels the viewer to pull out of the illusory screen space where subject matter tends to take over film reality.

Lippit

In watching your films again recently, but also following from what you have just spoken of, I am interested in your sense of framing. It has a peculiar tendency, although different from film to film, to make the familiar look unfamiliar, even peculiar and unknown. I am thinking especially of Reassemblage, where one looks at images that are part of a cultural vocabulary and yet the look of that film is so absolutely distinct that one begins to notice the very consistent but subtle sense of framing. Perhaps that also relates to your earlier comments about edges and borders. The framing doesn’t operate according to conventions, to the demands of balance or symmetry. Could you speak of your ideas regarding framing?

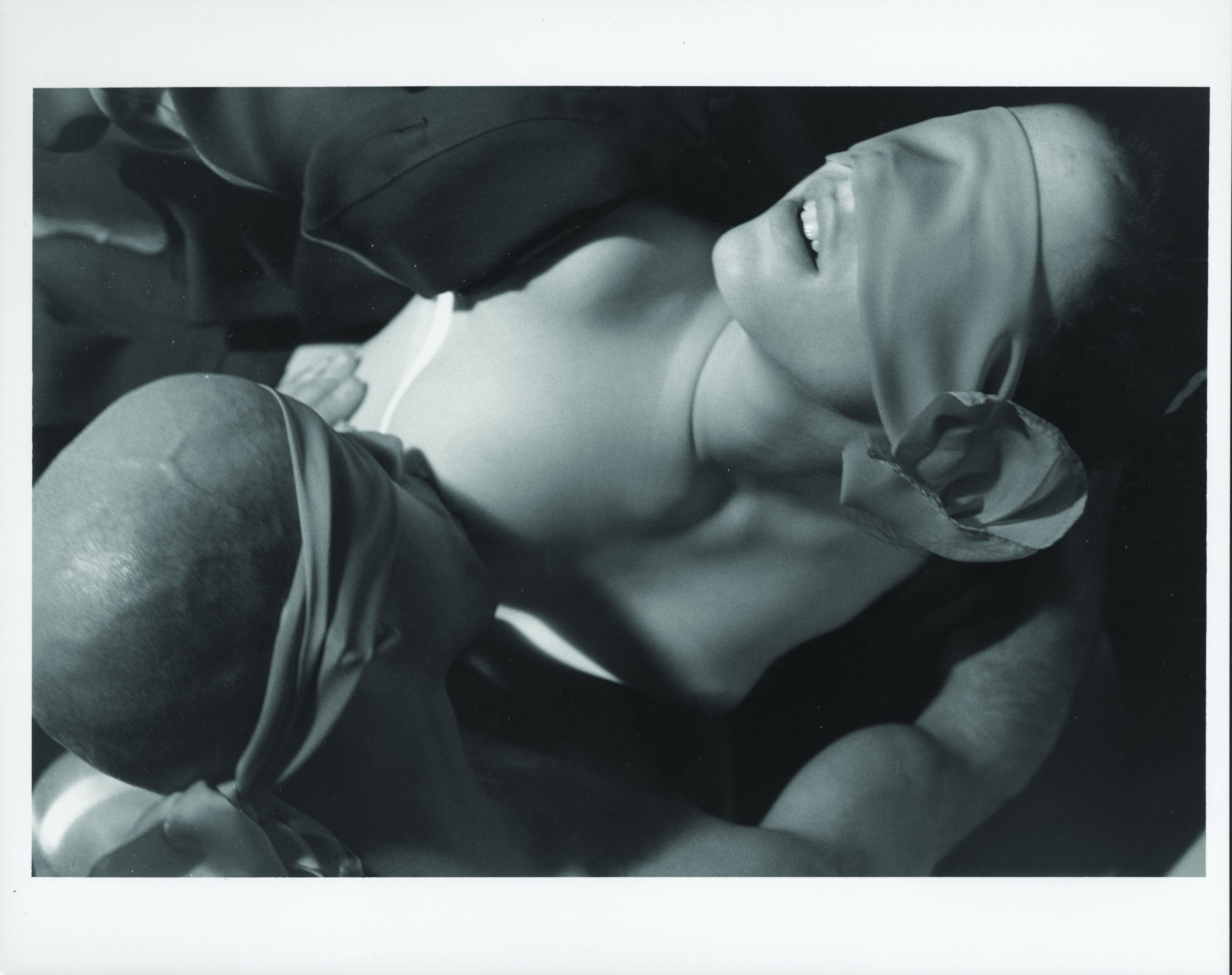

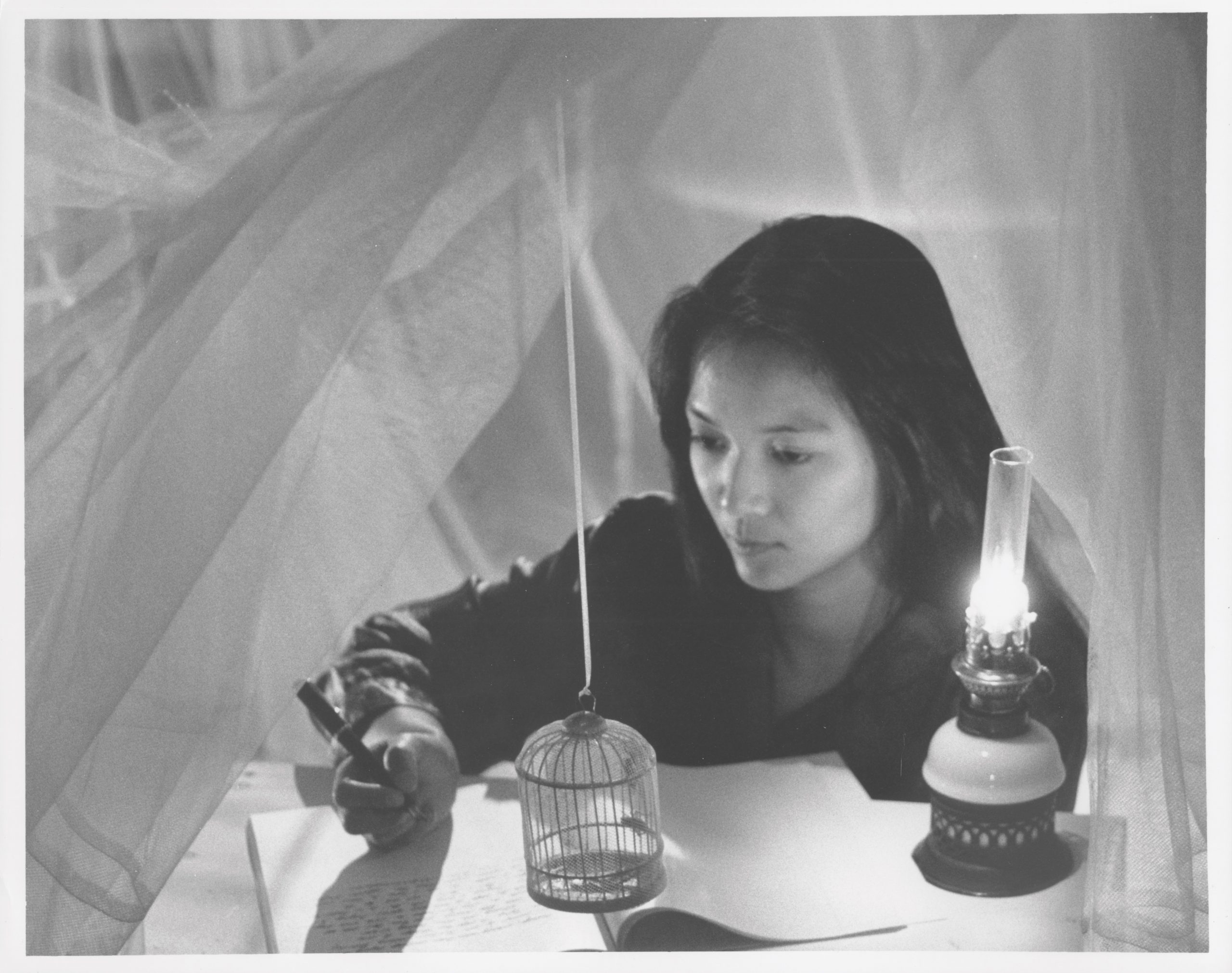

3 Still from A Tale of Love by Trinh T. Minh-ha and Jean-Paul Bourdier, Courtesy Moongift Films.

Trinh

Yes, actually we can go in many directions with this because it reminds me that when Reassemblage was first released, there were often, unavoidably, a couple of viewers in the audience at each screening who either praised the film or got very upset because they related it to a National Geographic product. Even today, I still occasionally encounter those kinds of response, whether in the U.S., in Europe or in Asia. And of course, there have also been instances where there is someone in the room who works for National Geographic who immediately says, “We would never accept such a film.”

Sometimes the mere fact that the subject matter is located in rural contexts or in remote parts of the non-Western world (what the Japanese film milieu commonly calls “ethnic films”), and the fact that, in addition, the images are bright and colourful, with no immediately definable or recognisable political agenda attached, are sufficient for some viewers to attribute the film’s look to the more familiar one of National Geographic images. I once said in response to a similar, aggressively voiced reaction that, ah yes, for some people all reds look alike, and that for them there’s no difference between the red of a rose, the red of a ruby and the red of a flag; nor is there any difference within the reds of blood flowing unseen in life and of blood spilled out conspicuously in death.

4, 5 Stills from Naked Spaces by Trinh T. Minh-h, Courtesy Moongift Films.

Trinh

Fortunately, a number of viewers do come to acknowledge on their own that what they first thought of as a National Geographic-type film does work on them, as the film advances, in such a way as to leave them ultimately perplexed and troubled. Days and even weeks after, they say, their perceptions of the film continue subtly to expand and to open onto unexpected views and directions. For me, this is largely due to a process of shooting and framing in which, as I mentioned earlier, the filming subject and the filming tools are always caught in the subject filmed. I don’t mind it when viewers in Europe link my films to those of Johan Van der Keuken, who is known as one of those truly “mad about framing.” I am not so much concerned here with composition, but as you’ve noted, I’m sensitive to the borders, edges and margins of an image—not only in terms of its rectangular confines, which today’s digital technology easily modifies, but in the wider sense of framing as an intrinsic activity of image-making and of relation-forming. Working with Jean-Paul Bourdier, who is an architect, has incited me to see in terms of space so as to decide where to put the camera and how to move with it. This is quite prominent in A Tale of Love, for example. While Reassemblage and a large part of Naked Spaces were shot intuitively with the camera placed very close to ground level, where most daily activities are carried out in African villages. Such a decision has an important impact on the image, but the frame itself is very intimately created while I am shooting.

Most of the time, if a good cinematographer sees an interesting subject and wants to use a pan, for example, she rehearses the gesture until the movement effected from one object to another is impeccable in its precision and certainty. In my case, I usually shoot with no forepractice and often with only one eye—the kino-eye, as Vertov called it. I may at times shoot the same subject more than once, but well, the first time always turns out to be the best, because when one repeats the gesture one becomes sure of oneself, which is what most cinematographers value—the sureness and smoothness of the gesture. But what I value is the hesitation or whatever happens when I first encounter what I am seeing through the camera lens. So the way one looks becomes totally unpredictable. Like wearing blinders and not seeing where one is going, the camera just moves with you according to the pace of your own body, or the pace of your camera pan. It is this attentive half-blindness that interests me. Rather than merely conforming to the ideal of seeing with both eyes while shooting—one inside, the other outside the lens and the frame so as to foresee one’s moves—I largely confine myself in the films I’ve shot to the eye that only sees reality via the camera. There is, in the look that goes toward things while letting things come to it unplanned, no desire to capture per se. You start a move and then simply continue it to see what comes into that framing in time and space.

Now there are films where I’ve worked with a cameraperson because I had to do more directing. Here, it is difficult to talk about one approach, because mine is necessarily mediated by the camera operator. In Surname Viet Given Name Nam, in the interview scenes of Shoot for the Contents, and especially in A Tale of Love where fiction intensifies framing, the sureness of the cinematographer’s hand is inevitable. But I value that element as well, when it doesn’t come from me. For it is then simply another element that contributes to the experience of film as an activity of production. Non-knowingness is an attitude, not a technique to perform. What is specific to the cinematographer also has a place, and even if that cinematographer does not decide on the framing, the gesture, rhythm and sureness developed are hers. Treating these as her contribution to the process also means that one necessarily creates a different space for the film. What you have is something, let’s say, between the open-ended process of the filmmaker and the skilled expertise of the operator.

Lippit

The images are beautiful in your films, strikingly beautiful—much more so than in National Geographic—and that may be an effect precisely of what you have described. Your description of the process of filmmaking for you suggests something more on the order of the sublime. Rather positing mastery over her medium, her subject matter, the filmmaker here loses herself in the process of making a film. It’s very different from the more popular notion of the filmmaker as a master of one’s craft, of one’s subject, of one’s space. Your description of the first gesture, the first movement as the one that you regularly prefer suggests a kind of dissipation or a loss of the self in the act of filmmaking. And the result can be a very beautiful image that emerges from the encounter with that dissipation, rather than from the assertion of one’s mastery in the form of a pan, or tilt, or some kind of practiced gesture.

Trinh

What you’ve just elucidated is very different from how people usually understand it. I feel much more affinity with the terms you use—“the loss of oneself,” by which one gains everything else, and hence no mere loss. The tendency among many, when I try to put this process of filmmaking into word, is immediately to recast it in terms of spontaneity and personal subjectivity. The first gesture is then viewed as the more truthful one. But the moment of spontaneity, which is so sacred for modernist art in general, has its limits. One can be quite clichéd, when being spontaneous. And there are often more instances, where instead of encountering elements of surprise or newness in spontaneity, one simply faces a form of reification of the individualist self.

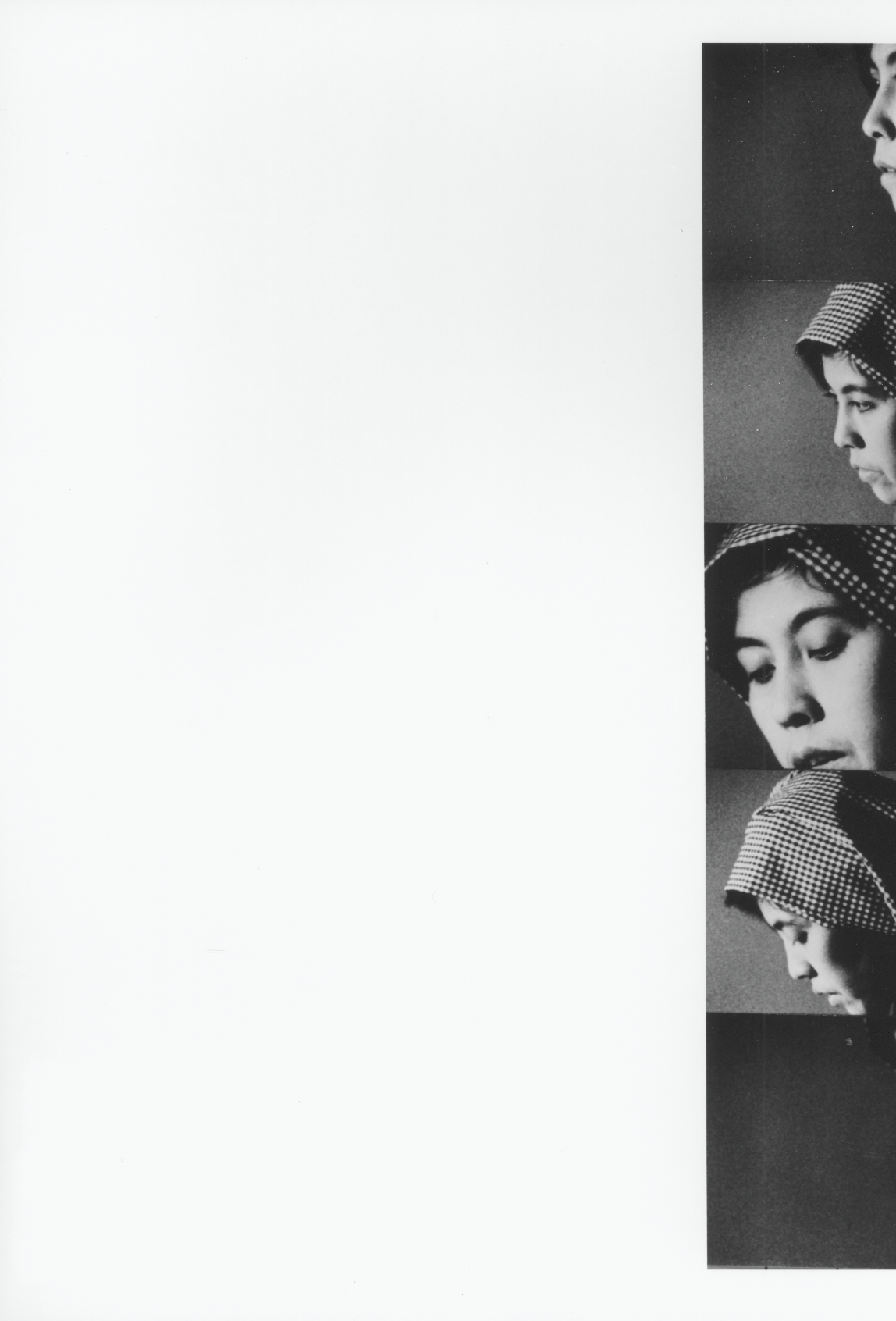

6 Still from A Tale of Love by Trinh T. Minh-ha and Jean-Paul Bourdier, Courtesy Moongift Films.

Lippit

The fantasy of a spontaneous gesture does suggest the emergence of an authentic or genuine self: A truer self that escapes in the inattention of spontaneity. Another feature that I find striking in your work is the adamant tension between images but also the sounds that are sometimes naturalistic and at others synthetic, artificial, and staged. Sounds are often broken, just when one is ready to be drawn into their flow. And one feels this at work in a variety of places, certainly I would say in Shoot for the Contents. During the interview with the Chinese filmmaker, for example, one recognises a very theatrical mise-en-scène – similarly in the interviews that constitute Surname Viet Given Name Nam. Do you see these tensions between naturalistic and synthetic representations as an element of your style, or do you see them as a dialectic that works between the notion of nature, naturalism, or things as they are, and the process of reflecting, commenting, filmmaking—“being nearby”?

Trinh

Neither one of those. Perhaps if I can find a way to say it on my own terms, it would be to say that what is viewed as being natural on the one hand and staged on the other belongs to a whole process. If one looks at the image in terms of representation, then I’m not simply representing “substance,” but I’m actually bringing out what one can call “function” or “condition.” In Shoot for the Contents, the image is mediated by the translator—a literal translator during the interview with the Chinese filmmaker, but also other translators heard or seen through the voices of the narrators and of myself as writer, editor and photographer of images of China. The fact that both makers and viewers depend here on translation in order to have an “entry” into the culture was clearly brought out in the sound-image. On one level, this interdependence made visible and audible may appear artificial, but on the level of its function within the process of producing meaning and images, it is totally natural.

This “natural” process is precisely what has been widely suppressed in films that try to get at “substance” while forgetting the importance of function and field in the mediation of reality on film. As the Indian philosopher Coomaraswamy said, one cannot imitate nature; one can only operate the way nature operates. When one thinks in those terms, the two currents you mentioned (one naturalistic, the other synthetic) are one and the same. To call attention to the subjectivity at work and to show the activity of production in the production is to deal with film in its most natural, realistic and truthful aspect. So I don’t see the separation. This largely applies to my first four films; with A Tale of Love, where everything was thought out down to the smallest detail, the situation is different. Ultimately, despite the contrasting way with which this last film fractures conventions of genre and of narrativity—or of psychological realism in acting and in consuming—its direction expands the one adopted by the previous films.

Lippit

In A Tale of Love, I was struck by, among other things, your use of colours and filters, which reminded me of the beginning of Naked Spaces, where you use a very saturated, seemingly tinted image. It creates a disorienting space because the colours and textures are so vibrant and voluptuous throughout the film that one begins to distrust one’s own senses. One can no longer tell what the so-called real colours of a scene are and those colours begin to infuse more than just the image, but all of one’s perceptions, projections, fantasies. It produces a kind of hybrid space, fantastic and actual. This colouring also seems to operate in A Tale of Love, which replays a previous tale, The Tale of Kieu, not as a historical citation, but as something that forms a hybrid text between a historical document and one’s interpretations of it. You make this clear in the film and in an encounter I saw you have with a member of the audience at a screening of A Tale of Love. She was an older Vietnamese woman who insisted that A Tale of Love was very different from the text she had studied in school. It seemed to be a perfect response to the film precisely because you suggest that there are always these hybrids that are forming between an external space grounded in reality and one’s encounter with it, which immediately creates some sort of space in between. Could you talk about your own motivation in A Tale of Love and the kind of interest that drew you to that project?

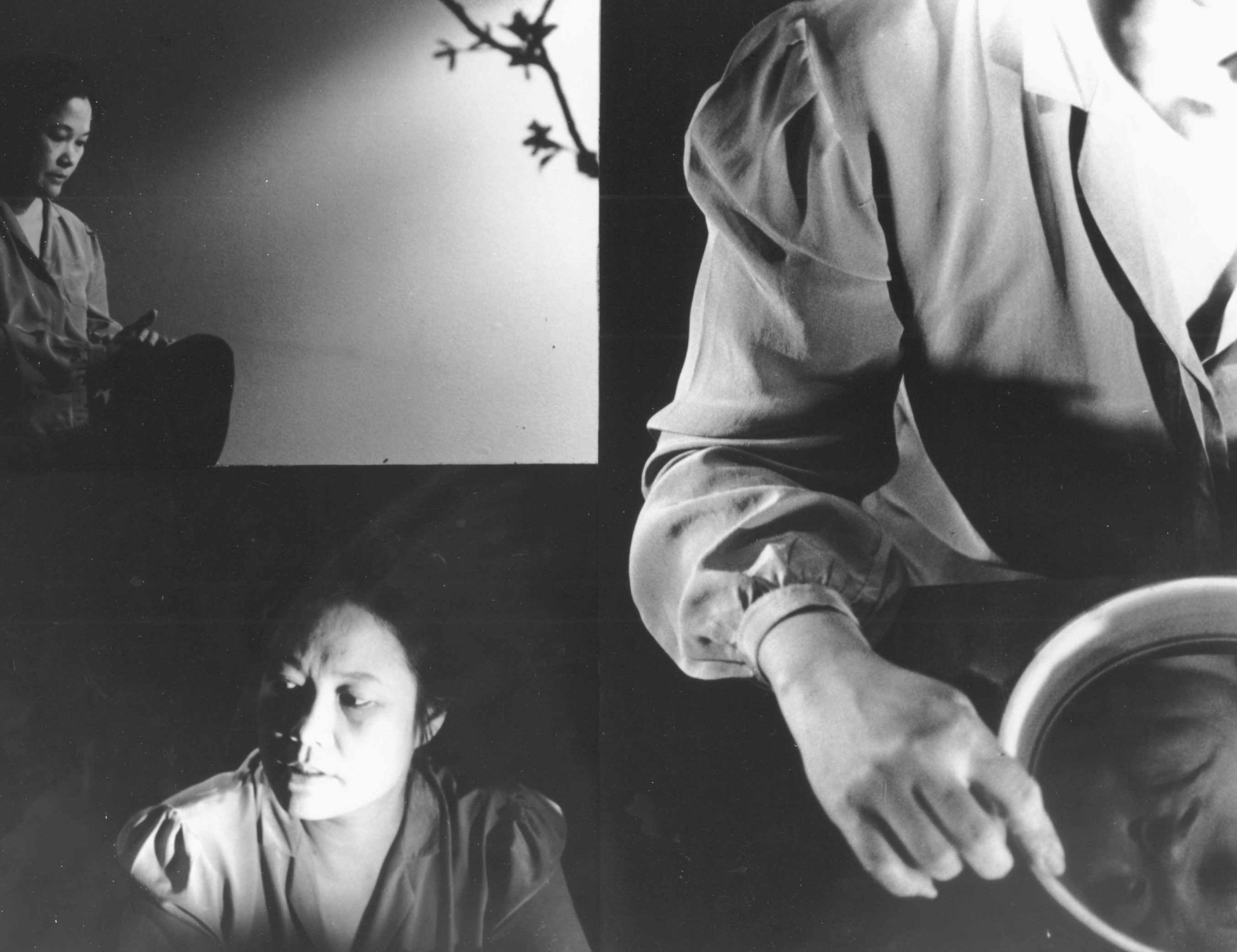

7 Still from Surname Viet Given Name Nam by Trinh T. Minh-ha, Courtesy Moongift Films.

8 Still from Surname Viet Given Name Nam by Trinh T. Minh-ha, Courtesy Moongift Films.

Trinh

There are actually two things in your response that I would love to discuss. First, I find it very interesting that you link the two films through colour. Second, I would come back to the twist you’ve brought out, which turns the Vietnamese woman’s negative response into an accurate response for the space created. Other members of the Vietnamese community who have seen the film have also given a number of very interesting reactions. For example, the epigraph seen on screen at the beginning of the film is a quotation of the ending lines of the 3254-verse poem. So “Why begin with the ending?” some asked and added, “Not only that, but afterwards, you enter the poem in such diverse places that it throws us off and we are confused.” One man told me, however, that because of these decisive cuts into the different parts of the poem, he saw through the film, the space between makers and characters. This was wonderful for me, even though he didn’t mean it in a positive way and was telling me about this undesirable split in which “your character is timorous and undecided but you are a very tough person.”

In the context of patriarchal Vietnamese culture, this was no praise at all. But then I was very curious and I asked more specifically why he thought so. He said the way I edited the film was such that every time he started settling in with a recognisable thread of the poem, the cuts again and again jerked him out of the story space. He saw in the edits what one can call the split of voices, which is an interesting reaction when compared to the tendency among Western audiences to identify the filmmaker with the main character. The question asked often revolves around whether the film tells of a personal experience. “Does this come from your personal life?” It makes things very difficult because certainly, I would have been totally unable to make a film if it hadn’t engaged me strongly in a personal way, but this has little to do with one’s own particular life. It would be of no interest if filmmaking and filmviewing merely invited identification rather than offered an encounter with what is larger than one’s individual self—that is, with one’s own spaciousness.

To come back to the question of colour, the tinted effect of that very first sequence of images in Naked Spaces actually comes from a rather “natural” process. The Kodak film stock we carried with much care with us over a period of nine months of travel across West Africa was, in general, quite reliable. But perhaps the heat played a role here, because amidst all this footage of accurate colours, we suddenly found two rolls that came out all red. When I called the lab to ask what had happened, nobody understood why it had come out that red—because it could have turned out slightly tinted, brownish or partly reddish, which is the usual case with older film stock. I was actually quite happy with the look, and since I didn’t cause this effect on purpose, I immediately saw it as part of this solicited “otherness” in filming.

Trinh

One of the film’s foci was the wall paintings of African dwellings, whose colours change with our perception and with the shift of light through the day. Light and darkness also structure people’s living spaces and influence women’s daily activities. There is a whole network of relationships built up in Naked Spaces between film, music, architecture, and social life through elements such as light, colour and sound. So the red incidentally caused by the heat appears as a natural process that easily finds its place in the main threads of the film. But by opening the film with this red sequence, I‘m also using the colour as a marker to invite the viewer to come into the film differently—with a light that can pull you far in, as differentiated from the green that pulls you out in the subsequent images; and a light by which you are projected into another state of mind even while you look at things “as they are.” When you encounter colours in such a state, as you so nicely put it, the dualism of inside and outside loses its pertinence; you are no longer so sure of how colours come to you, from in here or from out there. This is also how I see those houses: as you stay with a space and try to shoot it at different times of the day, you can see how light and colours are shifting in ways that open onto an inner landscape unseen by your daily purblind eyes.

In A Tale of Love, the question of colour is almost the opposite: you create it as an explicit part of lighting. Since we had to plan out all the details in a “narrative film,” with a large crew shooting from a script, we were dealing with a very constraining space. How is one to conceive of lighting when it is not simply used to fill in a space, to make things legible, to hierarchise and to dramatise according to psychological realism? By visualising it, for example, in terms not only of projection but also of absorption. The move here is to experience light as it is formed by the differing qualities of darkness and by the receptive properties of things (texture, tone, movement, reflective potential) in relation to their surrounding. Here, colour (as an attribute of life in Naked Spaces) comes in as one of the ways by which light itself takes shape. Just as the primary colours featured in the film stand on their own in a challenging relationship of multiplicity (rather than of complementarity), many of the lights that cross the frame have a distinct shape and colour of their own. We might say then, to use a term we discussed earlier, that this space in A Tale of Love is saturated with artificiality, which is fine with me because it’s what the making of a film with a script should acknowledge—a space carefully fabricated, if not entirely fabulated. But again, “artificial” is not opposed to “real” or “true,” for to materialise a reality, one has to resort to the “non-true,” and it is finally through the fictional—be it image or word—that truth is addressed.

Lippit

The story of colour in Naked Spaces is quite fascinating. It is as if the place, or the process, as heat had pressed itself onto the film directly, created a tactile trace of having been touched—a fortuitous disaster it seems. In a similar vein, I know you have discussed in the past your relationship to the interval, to uses of silence, or a variation of silence, speechlessness, which comes up as a motif in a number of your works. I am interested in not only the intervals of sound or silence that appear on your soundtracks, but the ways in which one feels those intervals or silences even when there is sound. Which is to say that the exploration of intervals or silence in your work seems to be at such a sophisticated level that it occurs even when it isn’t, strictly speaking, a moment of silence or pause, or some interruption of the sound. I was wondering if you could situate your interest in the concept of silence, and how it works in relation to your work, which is also very discursive too.

Trinh

When I discuss my work with an audience, what I generate from their reception of the film is something different from the film. I can’t tell them what “the film is all about” (which is what film reviewers often claim to do), for I do not wish to imitate what the film is doing. Rather, what I try to give to the audience is yet another space with the film. Very often discussants tend to confuse this discursive verbal space with the film and say, “it’s so complex, how can people who haven’t heard you understand the film?” But film and discussion are two different realities. Aside from the fact that you can’t assume that nobody understands because you don’t understand, “understanding” also cannot account for the whole of film experience; it is only one among the many other possible activities of reception. Once, in a public discussion of my work, a viewer made a very complicated and long-winded remark that ended disapprovingly with this statement: “Art should be simple.” And I agree. Even when the opinion comes from someone who can’t be simple in his response. Simplicity has always been a big challenge for artists. But the simplicity of a film has little to do with the complex responses it can generate. The simplest work tends to yield the widest range of readings and of critical thinking. Simplicity and complexity, as it is stated several times in Naked Spaces, really go together.

Similarly, silence expresses itself in many ways and can be said to be a whole language of its own. Sometimes speaking is a way of keeping silence and being silent is an effective way of speaking. This is often the case in repressed political contexts, such as for example the case of the calligrapher who appeared on screen towards the end of Shoot for the Contents, and whose answer to the question, “Why did you move from Shanghai?” was so clearly a form of silence, that I decided the best way to translate it, was not to translate. This moment of non-translation in a film that directly addresses the issue of translation has raised questions among a lot of people.

As you said, silence can be a moment when you don’t hear sound and this can be radically disturbing when taken literally. In film, silence usually means filling the soundtrack with discreet environmental sound like birds singing or water lapping, or else with what is technically called “room tone.” In Reassemblage I actually cut off all sound from time to time, creating this dreadful phenomenon for filmmakers known as sound holes. A very perceptive viewer told me that when he saw Reassemblage, because of the way that the soundtrack was cut off, he suddenly had glimpses of a spectral reality that addressed him directly. He said that it was an experience of death irrupting between images and in a way, he’s an ideal viewer for that film. Rather than simply equating a sound hole with a technical mistake, one can ask what effect this has on the viewer, what reality is brought about? The reality of something we call death, or among others, the reality of the room in which the film is showing—the snoring of the audience, the squeaking of seats, the noise of the projector or the pulsation of one’s own body, as Cage musically experienced it.

It’s very difficult to simply talk about silence as a homogeneous phenomenon. As you’ve noticed, even when there’s sound or a lot of talking, you can still feel that interval. I really appreciate that, because, unlike with the films shot in Africa, Surname Viet Given Name Nam, Shoot for the Contents and A Tale of Love feature language in its excess as it outdoes the will to speak and to mean. There are also moments when words become nonsense, which is another aspect of language that I often work with humorously. After so much speech, you come to a state where opposites really meet. You may say or hear one thing but you’re supposed to mean or to understand exactly the opposite, which was the case with such terms as left and right, right and wrong, as related to China’s politics. But that’s the nature of language. When one pushes it far enough, words start to mingle, they are no longer opposites and the more one goes into it, the more one sees how these words used excessively can also silently open up a critical space.

Lippit

What I find especially liberating in your films is the way in which you track the movement of language from a place to its destination. And frequently, it doesn’t arrive at its destination, which is a much more compelling way of thinking about language, communication, all of the complexities of its transmission, and translation. That non-arrival, or missed arrival seems much more provocative and much more familiar, even, as an experience than the shot/reverse-shot convention in which movie conversations are usually sent and received. In another interview, you relate the experience of a translator running up to you frantically and saying “But there are two voices here, which one do we translate?” The fact that things are lost or miscommunicated or fail to arrive at their destinations is hardly frustrating, but actually a relief to see in film, because it really begins to address the circuitry of language. It seems that in your films the interview is never a stable phenomenon, even from film to film, but something that is addressed and created as a space each time anew, never occurring in the same way. Each space seems to be driven or motivated by the particularities of that space and your relationship to it.

Trinh

If people thought about language in the way you just described it, then my films are very simple. It’s the same with my books. I do hear from a number of academics that my books are very difficult. And I don’t deny this. On the other hand, I’ve also met people who left school at the age of fifteen or who have no training for theoretical thought. They come across these books by accident and they can’t read many pages in one go, but they have no concern for that, they just steadily read a few pages at a time and say it’s incredible, because they feel a lot of affinity with the process of my thought and can follow it so well. If one simply observes how language operates—creating all these circuits within itself, as you said—and how it works on us constantly, then these films are very easy to “understand.”

When an interview is dense and intense, as in the case of those in Surname Viet Given Name Nam, then even in moments when one is not in front of the interviewee, the conversation continues, not in one voice, but sometimes in several voices, or in fragments that come and go and get superimposed on one another. There’s nothing difficult in the film when one thinks inclusively in terms of what language does to us—how it speaks us as we speak it—rather than exclusively in terms of ourselves as the ones who manipulate language. Any one of those instances that may irritate the viewer by its so-called incomprehensibility is for me as clear as a river. They happen all the time in our daily reality with language.

Regarding the anecdote about which voice to translate when there are several simultaneous voices, I was amazed by the Japanese solution. Actually, with Japanese characters, that problem did not even arise; my distributor at Image Forum simply decided to have one voice subtitled vertically, the other, horizontally. Not only do calligraphic characters destroy the image much less, but you also have this flexibility of going vertical or horizontal.

Lippit

When A Tale of Love was about to be released there was a small fervor that Trinh T. Minh-ha had made a narrative film, and there was something of a scent of scandal about the whole thing. When I heard this rumour, I was little surprised because it is not as if your previous films could be classified as strictly non-narrative work either. They had elements or traces of things that one might call documentary, for example, or experimental or art film, or music film. And then when I saw A Tale of Love I was reassured that this wasn’t a narrative in the way that people seemed to be disparaging the term either. Certainly it was a narrative and it engaged aspects of narrative. But it was also done in 35mm. Could you talk about your decision to work with this format and this narrative structure? What prompted you to explore this particular set of elements?

Trinh

It’s just like with the colour red discussed earlier in Naked Spaces. The decision was bound to circumstances. I didn’t have the budget to shoot a “feature narrative film,” not even a budget for 16 mm. So in a desperate move, the line producer called everywhere searching for donations. Panavision donated the camera equipment in 35mm for the whole shoot, rather than in 16mm as we had asked, which was such an incredible thing. But I paid dearly for that, because I got stuck after the film was finished. The final edited version was completed in 1995 but I had to wait until 1996 before the film could be released in an acceptable form because there was no money left to make a print.

Certainly, there’s also another decision that comes into play. And as you said, it’s not so much a question of narrative versus documentary, it’s more a question of exploring a different terrain of cinema. Since I’ve explored at length the terrain of, let’s say, information and truth, I wanted to explore this other terrain which is that of the lie and its truth in love stories. I wanted to see what happens when you deal with something as commonly consumed in our society as the love story. But as you can see, despite the difference in realisation, the direction explored is similar to the one taken in the previous films.

Lippit

In each of your films, one senses the particularity of a place and a space that seems to orient the film. One feels that the space is dictating or directing the movements of the film, a mixing of geography and fantasy, experience and projection. Knowing that you have spent some time in Japan recently, and that you are also working on a new project, I was wondering if you could talk about your new project and also about your sense of Japanese space?

Trinh

It’s difficult to talk about a visual space before you get a chance to see it realised on film or video. I’ve just only started work on it, but let’s say that after having been to Japan, I think, five times, my experience of the culture during this last four-month stay, which was the longest stay, has changed quite a bit. It was a thoroughly demystifying experience, although not in a negative sense. You just have a reality that is differently nuanced, less romantic, but also less exotically other.

As with many foreigners, I am drawn to the spiritually ritualised aspects of Japanese life and art. The integrated dimension of aesthetics and ethics has been quite striking in a number of Japanese works, for example. I am very attracted to shooting in Japan partly because of its architectural landscape, which really favours the graphic line and the mobility of sliding frames. Here, the line between outside and inside is always shifting. It seems as if everything—from the art of building houses to the way the railroad network functions, or the way dance and music structure theatrical performances and festival parades—partakes in a system whose organisation is largely based on micro-structures or on prefabricated cells (the melodic, the rhythmic, the action-propelling and the structure-bearing cells in a parade, for example). There’s also a striking encounter between light, colour, and graphics in the scenography of life and stage events that I would love to work with. But as always, I have to remain very flexible as to what I can do, since I don’t work with unlimited finances and everything still depends very much on that. I have to take into consideration the fact that maybe I will not be able to get permission for the locations where I would love to shoot, such as in temples, since the next film is very much related to a spiritual quest.

At the end of this millennium the notion of spirituality may continue to raise skepticism because what is spiritual is often identified, at least in the modern world, with mystification and institutionalized religion. A return to the traditions of old is also to be rejected as long as these are viewed only through activities of retrieval and of imitation rather than of creation in the present. This, I think, is the very problem we face today, both in the modern East and in the West, with our inability to see the spiritual in any other way than smugly and narrow-mindedly, as a form of parasitical occultism and of transcendentalism. The situations with Tibet or with Islam are glaring examples. As a spiritual force that gathers people across geographies and nations, Islam certainly stands, despite all controversies, as the one visible power that continues to challenge the West at the end of the millenium. It is necessary in these times to look at spirituality in a different way. And certainly, Japan has had a strong tradition of writers and filmmakers who have struggled with this dimension of life, from which I also draw inspiration.

Lippit

These glimpses are very intriguing. The quest for a spiritual existence or identity, a rethinking of spirituality, should be of interest to late-capitalist Japan as well. Thank you very much.

9 Still from A Tale of Love by Trinh T. Minh-ha and Jean-Paul Bourdier, Courtesy Moongift Films.

10 Still from A Tale of Love by Trinh T. Minh-ha and Jean-Paul Bourdier, Courtesy Moongift Films.

11 Still from A Tale of Love by Trinh T. Minh-ha and Jean-Paul Bourdier, Courtesy Moongift Films.

Published with permission of Trinh T. Minh-ha and Akira Mizuta Lippit, 2013.

Copyright Trinh T. Minh-ha and Akira Mizuta Lippit.

First published in Japanese in Intercommunications (Journal of Art and Technology, Tokyo, Japan), No. 28, Spring 1999 (for part I); and No. 29, Summer 1999 (for part II).

Published in 2005 in The Digital Film Event: Trinh T. Minh-ha, by Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York.

Essays

Calendars (2020-2096): Heman Chong in Conversation

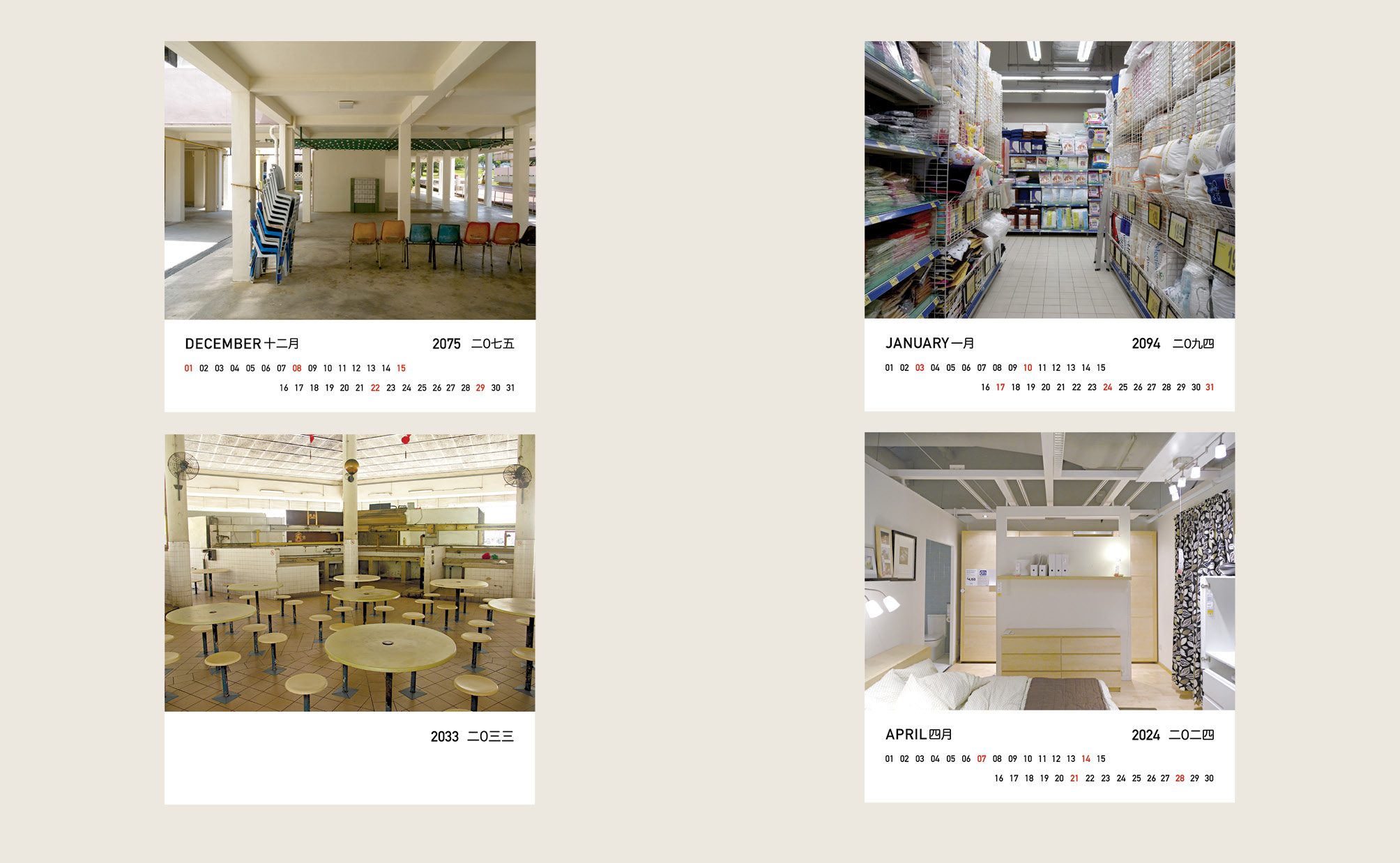

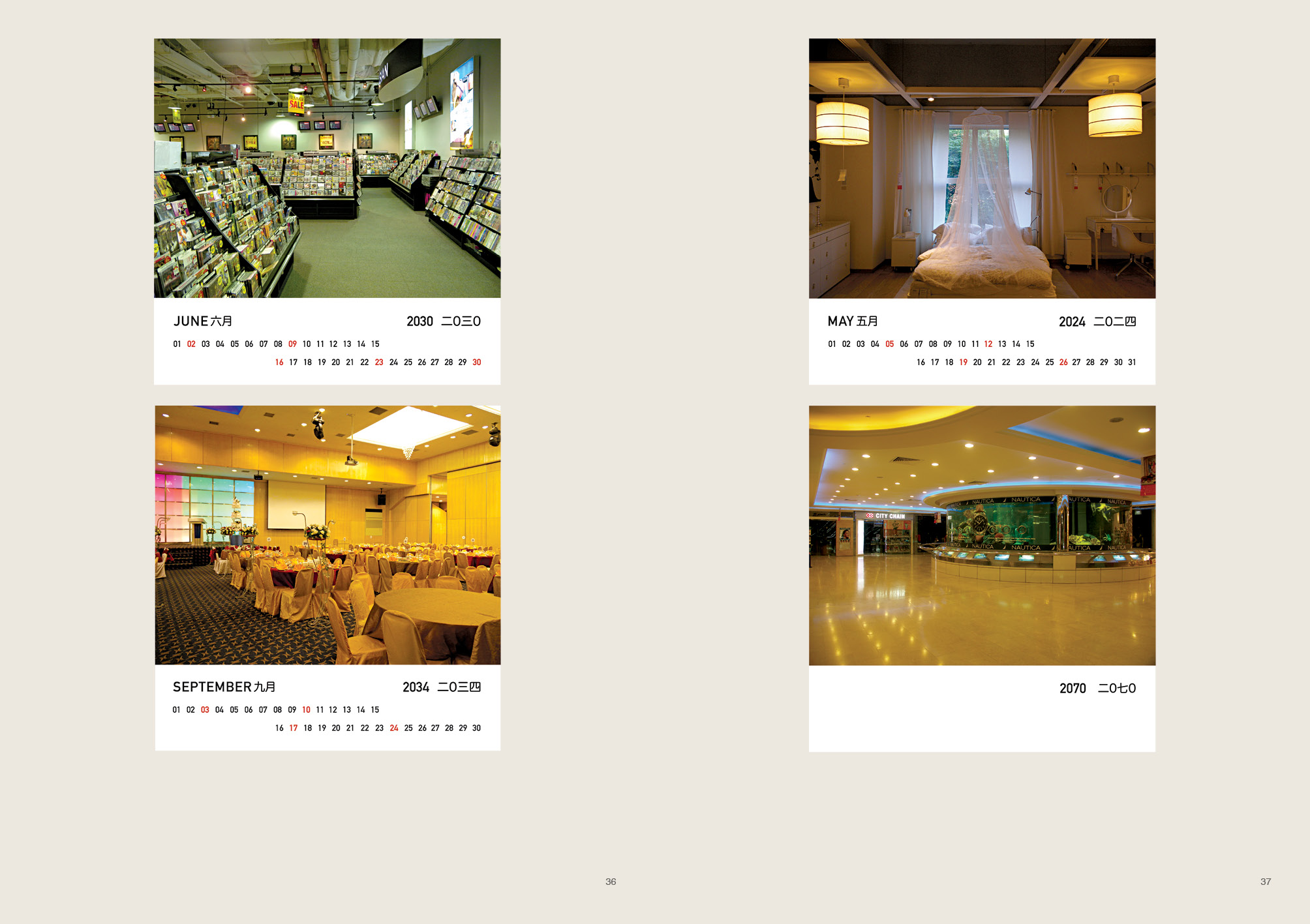

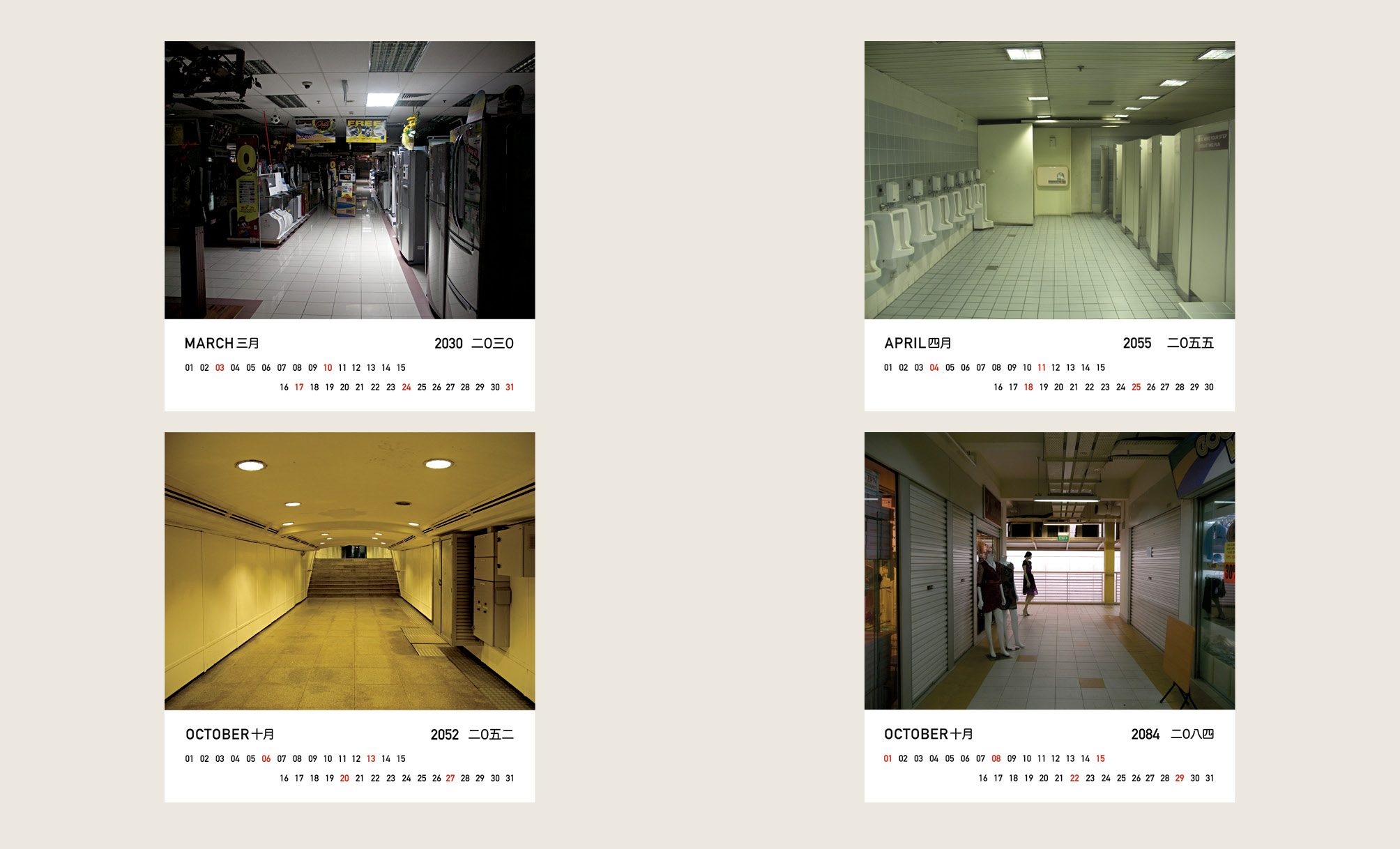

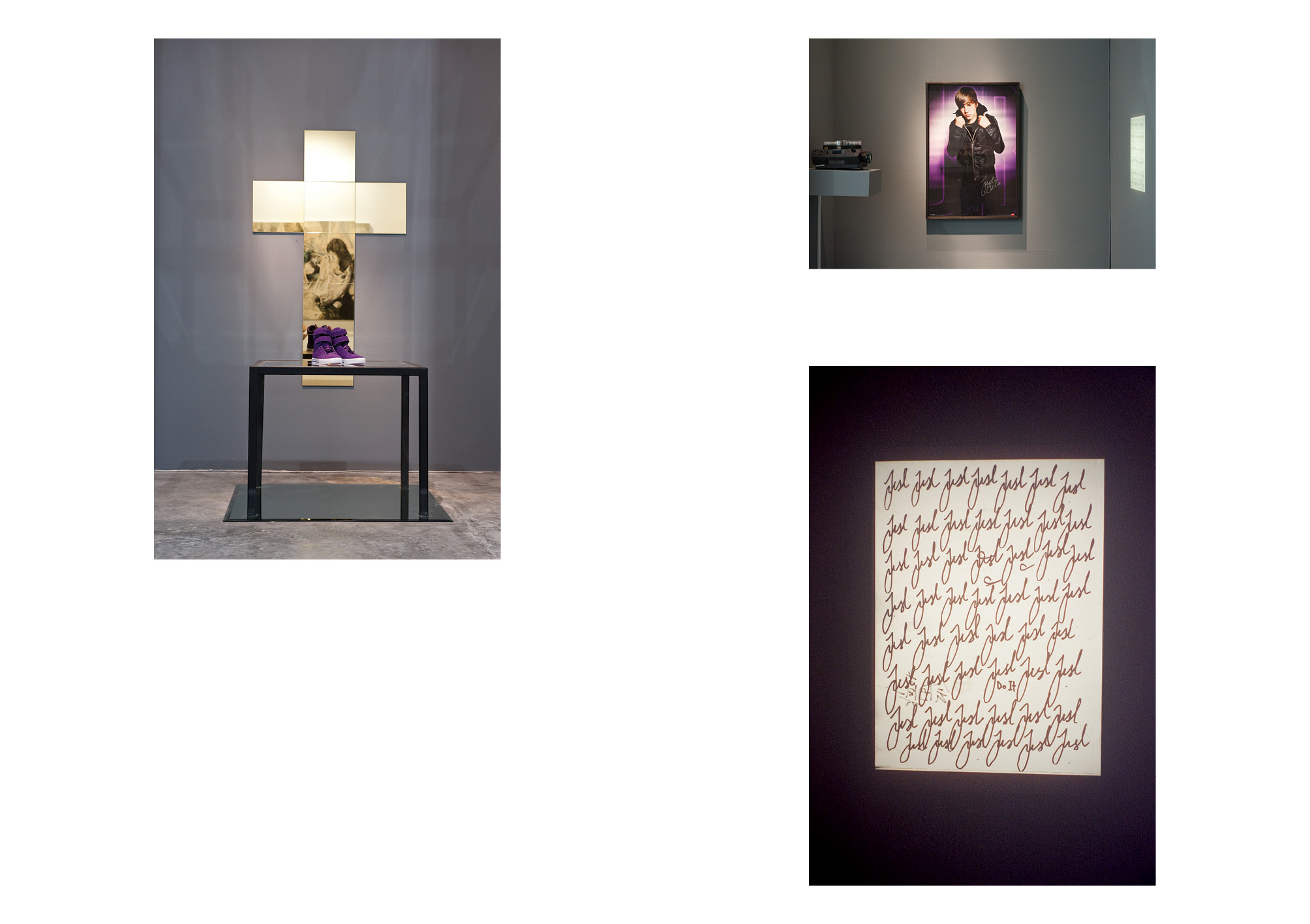

The following article was published in Calendars (2020-2096) for the exhibition of the same title of Heman Chong’s work, in 2011 at NUS Museum, Singapore.

Heman Chong’s installation at the NUS Museum consists of 1,001 photographs presented as 2020 to 2096 calendars. Collated over a period of seven years, the production of these images was guided by a set of simple rules: these photographs are taken during periods of public access, and that they are emptied of people. Photographed in various parts of Singapore, places visited by the artist included public housing estates, shopping malls, eateries, tourist sites, and an airport; these emptied spaces were conceived as tableaux, within which subjectivities may be deployed or e nacted by their viewers, complicated by a conceptual interplay with the calendar as a notion of linear time. Chong describes the work, installed in a gridded format occupying an entire gallery, as a “dream machine”, an intriguing apparatus without an operations manual characterised by its servitude to the impulse of imaginings rather than objectively determined: “How can this construction be useful to anybody except myself?” Heman Chong discusses Calendars (2020-2096) with Ahmad Mashadi in relation to his expansive practice as artist and a curator, and authorial strategies that involve collaborations, appropriations and quoting, and synoptical devices that facilitate modes or reception.

Mashadi

You work with multiple projects moving quickly from one to the next; Calendars (2020-2096) consist of vast set of images, completed over a lengthy period. You described the project’s immensity by its references to “time, space, situation”. Conceptually one imagines the project sustains a particular approach of practice. Where do we start?

Chong

We can start by talking about the value of coherence in an artistic practice that is situated in the context of today; how can we measure the value of an artist’s contribution to the language of art, and in turn, to the landscape of cultural and knowledge production? Viewing the situation from my perspective as a relatively young artist from Singapore who has more or less discarded a trajectory of production that revolves around the usual suspects of specific mediums like installation, painting, sculpture as grounding points (which is something that is prevailing, not only in Asia, but across the other continents as well), I am much more interested in working with these methods as conceptual vehicles for a basis of discussion about issues and things surrounding us. For example, I am interested in how a series of painted images; images of book covers could, very quickly become, an auto-biographic tool which then very quickly shifts into a series of hysterical recommendations to people of which books they should read. So, in a way, it’s somehow about surpassing the need to focus on one’s ego, to extend a dialogue beyond the idea of the self into something much larger.

Mashadi

That is interesting. It is that very question of coherence in which many had commented on a sense of ambivalence on your part. We can go into the specifics at a later stage of the discussion. For now, let’s push on with some generalities. Where the demands of contemporary production involve multiple negotiations, the coherence being referred here disavows any formal categories and instead, as you pointed out, revolves around manners of working and attitudes. In other words, you develop conceptual strategies and it is within these conceptual strategies that we may locate productive perspectives of an artistic practice, an autobiography as you put it. There are so many things to unpack here. Let me start by asking you if you can expand the phrase you beautifully used “...to extend a dialogue beyond the idea of the self into something much larger”. It seems to me it demands another way of thinking about the “authorial” and “authorial strategy”, not effacement of self, but rather affording into the practice forms of slippages arising from contexts, peoples, and encounters...

Chong

I feel very strongly that our identities are constructed around the things we associate ourselves with. And I am also conscious of the fact that I exist in a very privileged situation where I have an abundance of associations to work with. The questions that often haunts me are: What will I do with all this material? Is there a way to use it so that it reflects both a private world and the world at large? How can this construction be useful to anybody except myself? Do I want my work to be useful at all? One strategy that I have imagined over the years is to perform a set of recommendations, namely of novels, to the ‘audiences’. This, of course, extends directly from the conceptual legacy of ‘pointing at things’. I feel happy when people email me to talk about a certain novel they have just read because of a painting that I made, or a mention of that novel in an interview, and how we can come together not to talk about me or my work, but to discuss certain interpretations of that novel. For me, it’s important to have such a basis for any kind of conversation, a plateau, where we are teaching each other something, learning from one another.

Mashadi

I guess you are referring to ‘identities’ in the potentials as something indeterminate, something situational perhaps. The projects of where you work alongside others carry risks. Based on what you have just said, the writing project Philip (2006) is an interesting one... you brought a group of people together—artists, designers, curators—to initiate a ‘science fiction writing workshop’ eventuating with a publication. Here the term collaboration is structured with pre-assigned roles and process, and the outcome—the book—identified. The otherwise singular voice of the author is replaced with a sequence of different voices, each simultaneously pushing and pulling as one struggles to sustain one’s intertwined status as an individual and as part of a collective. Here, in many ways ‘process is form’, and that at times necessitate one to embrace the potentials of failure (at times we fetish over it). To what extent, as a project initiator, do you surrender to risks?

Chong

I guess the thing about empathy is that when we start to feel for someone, when we begin to bridge ourselves to another, we start to change. And there is a great desire inside me to want to change. Not so much as a moralistic exercise (for the better) or having a day out (for the worse), but something that falls in-between the two (for better and for the worse). No, I don’t really want to consider risk as part of the equation, because I’ll be too afraid to do anything that might foster change. Within the context of Philip, we soaked ourselves in this atmosphere of being impulsive, of writing whatever we wanted that immediately became part of a larger imagining. It was super interesting to how the entire ecology within the novel was literally constructed out of the multiple viewpoints that each of the participants brought with them, and how their cultural and emotional baggage contributed to the minute details that became the architecture of the world. At the same time, it became very clear, very early on in the project that two of the participants in the writing workshop, Steve Rushton and Francis McKee, both had this amazing ability to be able to juxtapose and edit the worlds into a singularity. There was a lot of trust involved in that situation, where we knew that our input into the novel would be weaved together in a way that could become something... readable.

Mashadi

Does it prompt a newer regard in your thinking about the public? You earlier remarked on the importance of public reception to the works. How easy was it to engage a readership where the integrity of art in its final form should be negotiated to solicit the potentials of collective production, a fluid plot that is contingent on accumulative and sequential contributions from each participant?

Chong

We discovered that there is an audience that craves to encounter a process as such. And that finally, it was this process that drew them into reading the novel. It has also to do with the distribution of the novel. Initially, we printed a hundred copies as a first edition, to raise funds to cover the production costs of the project (which worked) and then we had the second ‘run’ parked within Lulu, a print-on-demand service. We also distributed the novel freely as PDF, without any charge. Who wouldn’t want a free copy of a science fiction novel?

Mashadi

Joint authorships like Philip is one aspect of your practice. Ends (Compiled) (2008) takes on a different approach, It affords you to take on a ‘collaborative’ strategy that is appropriative rather than one that involves negotiations. You chose passages from published books written by various authors. Here we can return to your thoughts on a practice having an autobiographical inference, in a sense that passages in Ends, actually may suggest ways predicaments interact with ironies or suspended resolutions sketched out by these respective authors. You chose from Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker (1937) “... striving to win for their race some increase of lucidity before the ultimate darkness...”. It is about the idea that entity is part of a collective organism, and knowledge is relational to one another, finality unattainable...

Chong

On some days, I sometimes feel that I am eternally damned to just merely being someone who can quote very well, and never seen as a artist who can actually produce something original. It is, perhaps, my greatest anxiety in my life. Even if appropriation has very clearly been validated by both institution and individuals as a completely legitimate way of producing meaning, I guess, personally, I’ve always wished that I never used it. Somehow, it’s something that’s way too flippant. Too easy... Even though Ends (Compiled) was in fact, an extremely well choreographed work, both in the selection of texts and the way it has been presented as a sculpture, I remain dissatisfied. At the same time, it remains to be a very useful tool especially when I’m asked to ‘interact’ with a certain preconceived idea from a curator about a certain situation or a space... what I’m trying to say is that appropriation is great when you need to develop something like a ‘non-denial, denial’ or a ‘non-event, event’.

Mashadi

By the phrase ‘non-denial, denial’, you are referring to attempts in developing formal and conceptual tensions that resists curatorial or institutional affirmations?

Chong

It is not so much an act of resistance as much as a reminder that, like it or not, we live in complex times and as a result, frameworks drawn of out of easy categorisations can fail in an extremely uninteresting way. Just take for example, how contemporary ‘Southeast Asian’ is being defined: most curators would gladly take on tribalism and animism over conceptualism and intellectualism...

Mashadi

We had discussed the question of the ‘authorial’ as an artistic predicament, but in many ways it is within your curatorial practice that the question seems most urgent… Difficult to tell if it is an extension of art practice. We worked together several times in particular for We (2008) and Curating Lab (2009) where you referred to the collation of materials we gathered for the exhibition and the artworks as ‘collecting’. It seems to me this is a way to remind ourselves that they have agency while at the same time ‘possessed’ in the manner in which the quotations you just referred to have resonance in saying things that may (or may not) be defined to one’s positions.

Chong

The two roles are interchangeable and I have never sought to define them in strict terms. Just as I have never really played the ‘Asian artist’ card in an explicit manner (especially when invited to shows in Europe and North America), even if a lot of my work deals with a lot with the various trajectories in which intellectualism and conceptualism has failed to take root in Southeast Asia. I don’t have a desire to take up mantles that would allow for easy compartmentalisation. I have observed, in the past ten years of being an artist and playing such a loosely defined role, it has this effect of distancing myself from curators and gallerists who find my work ‘too confusing and too difficult’, but at the same time, I have also encountered a group of curators and gallerists who are completely into this definition. For example, I know for a fact, that the Singapore Art Museum is one institution that has dismissed my work as being ‘too international’ for their taste.

Mashadi

Yes, identities forced along notions of ethnicity and nation can be quite a burden, which good or bad, are forms of currency in art-making and reception, here as much as elsewhere. I think it is not a question of resistance, but rather perhaps insisting for a critical engagement that acknowledges the contingency of multiple contexts and references. Your focuses on technology, society and fiction, and your methodical, almost hyper-rationalised use of texts and graphics are calculated to insist this is a difficult proposition?

Chong

I refer to a work that I made in 2009 entitled The Forer Effect, an appropriation of a text within an experiment by Bertram R. Forer that has the same nickname. He issued a personality test to his students and told them that they would each be receiving a unique personality analysis that was based on the test results. They were to rate their analysis on a scale of 0 (very poor) to 5 (excellent) on how well it applied to themselves. In reality, each received the same analysis:

‘You have a great need for other people to like and admire you. You have a tendency to be critical of yourself. You have a great deal of unused capacity which you have not turned to your advantage. While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them. Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside. At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing. You prefer a certain amount of change and variety and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations. You pride yourself as an independent thinker and do not accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof. You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others. At times you are extroverted, affable, sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary, reserved. Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic.’

On average, the rating was 4.26. Only after the ratings were submitted, Forer revealed that each student had received identical copies composed by him from various horoscopes of the day.

In light of this, what I’m trying to say is that while words don’t come easy to most people when they are trying to define a situation, to some, they come a little too easy.

Mashadi

Let’s discuss this obliquely in relation to the current Calendar project which was conceived sometime back, before you left Singapore for New York. You had undertaken a number of photographic book projects focusing on Singapore sites before initiating the Series. What were they? What did you aim to achieve in these book projects?

Chong

I never have had a master-plan for anything in my life. Mostly, I just improvise and adapt along the way. The reason why I mention this is because, when you look at Calendars (2020-2096), you will get the impression that from the very beginning of the project, I knew what I want to do. Which is completely not the case at all. When I began to photograph these interior spaces accessible to all (most) people, I did it because I was searching for a new idea, a new beginning, a new way to collect images. I believe very strongly in the power of observation, where you will literally just look at something, break it down in your head in the most logical way possible and then ‘archive’ that sensation of that image. I don’t have a photographic memory, and that is why I rely on photography for that part of the process. These spaces, they intrigue me, on a structural level and also on an emotional level. Somehow, I know that they are so susceptible to change, to every sway of policy, to every new wave of capital... In a way, it was the same with the books I made, about specific sites in Singapore. The first was about Telok Blangah Hill Park, where the National Parks Board commissioned this totally insane structure which runs from the foot of the hill to the top, something we came to know of as ‘Forest Walk’. I am inherently interested in how ideas affect spaces, and how spaces can be representative of certain things that we (or more aptly, ‘they’) would be concerned with, at a certain point of time. In this case, somebody really had this idea of a nature reserve that is accessible to ALL, including the least attractive people of society, the handicapped—people without any means of mobility. They built a huge metal structure, which functions as a giant meandering ramp up (and down) this hill. I find this completely fascinating, how they even could start of conceive of such an idea. How does a conception about a GIANT RAMP UP A HILL start?

Mashadi

From the perspective of production, the project is unburdened by any assumptions on outcomes. I understand that it is largely conceived along the need to generate fresh trajectories of practice, but the notion of cities suddenly emptied of its inhabitants is rich in its potential, not least in science fiction. You spent time in places like shopping centres during opening hours waiting just for the right moment to capture a scene without anyone present. Is there a conceptual underpinning here defined by ideas connected to plausible settings in science fiction? Or is there a commentary element—dystopia of sorts?

Chong

I would say that Calendars (2020-2096) locates itself within a conceptual framework of utilising gestures, in this case, that of waiting and appropriating images within a specific moment, that moment of absolute emptiness, which can be quite rare considering how densely populated Singapore is. But at the same time, it has this dimension where I am also interested in formulating a kind of fictional landscape, one which reflects all the concerns of dystopic narratives, especially of the ‘last man on earth’ genre. This genre often deals with a global cataclysm which results in the near annihilation of the human race. Whether it’s an ecological disaster or a full-blown biochemical infection, the stories usually become humanitarian; they are stories of how humans can survive the worst possible situations.

So in a way, I am interested in staging the landscape in which these stories occur, and to use them as banal images for a banal activity, that of recording time...

Mashadi

Based on your earlier remarks, the Telok Blangah project seems to conceptually point towards the ironies and contradictions of spatial production... and in some ways in same manner in which we regard science fiction as having its furtive roots of criticality with the contemporary, the Telok Blangah and Calendar projects seek a placement into the current day.

Chong

But also to suggest that our imaginations are also important in placing ourselves into the everyday, that we have possibilities to imagine ourselves inside and outside of situations. For me, this is one of the crucial skills of a good artist.

Mashadi

The decision to present those images as calendar illustrations was made during the period of photography?

Chong

Yes. I took seven years to complete the entire project, and a huge part of it was to allow for a series of divergences to occur without any kind of prior planning involved. So a lot of it was left to chance, and one of the results, for example, was to use the photographs as accompanying objects to the actual marking of time.

Mashadi

How many images are there in total? How are these images organised according to the years, and are there particular ways in which the images are being clustered? At some point you decided that the large body of images were best mobilised as an exhibition. You mentioned earlier about the forms of subjectivities and your wish to facilitate through these images. How do you intend to display them? It seems that placing the images and into a calendar format allows you to intimate towards some of the conceptual interests you were talking about. The subject of post-apocalyptic (or even post-rapture) world may directly be inferred. The calendar, the suggestion of an impending event, gives a millenarist tinge to the work? And the condition of present as another.

Chong

There are 1,001 images in all. I arranged the photos according to a series of categories, which are evident in the spaces themselves—corridors, shop fronts, big rooms, small rooms, etc. There are also some categorised by sites—Depot Road, Haw Par Villa, IKEA, etc.

There’s a lot of contestation with the actual presentation, and I think it might be best at this point to follow a certain grid within the space, and to show all 1,001 pages containing all seventy-seven years of calendars within a single plane. I chose the year 2020 to start the calendars as a result of an observation about the idea of 2020 as the year in which all the problems in the world could possibly be ‘solved’. In many political press releases, we can notice this kind of promise, and of course, we now understand that these projections do not necessarily mean that any of the promises can or will be fulfilled. We constantly have to manage this sense of disappointment when it comes to such statements from the people that we thought we could place our trust in.

Mashadi

In that respect the images can also be taken in relation to specific potentials, beyond a universalising notion of time markers resplendent in economic or social programmes. These are specific locations whose economic, social and even political utilities are shaped by prevailing structures and responses to the same. Does that put you in an uncomfortable position as observer/commentator, offering a critique on the politics that informed the production of such spaces and their dystopic inevitabilities?

Chong

I don’t see it as an uncomfortable position at all. I think art is a language in itself, and has its own potentials. I don’t want to apologise for speaking this language, but at the same time, I acknowledge that this language can only be understood by a very limited community, often causing a lot of misunderstandings when art projects are discussed within other fields like sociology or politics. In recent years, a lot of artists have been working in this field of producing knowledge, and while I appreciate a lot of the material generated from these projects, it is something that I don’t want to do, at least not in the way of producing knowledge like how an academic would. I prefer to work along the lines of subjectivity and speculation, and mostly, I just let things go wild, let them become hysterical. In my work, I don’t want to place the emphasis on ‘making sense’.

Mashadi

Yet there are formal elements that insist we look at them as enquiries of spatial organisation, order, placement, tonal value etc. In that sense there is a generousity that imbibes the viewer’s place. These images cam be ‘free floating’ too, their significations negotiated by the viewer themselves. Their post-apocalyptic reference inflected by conditions of spectatorship...

Chong

It is about constructing a kind of dream machine, a space which allows for dreaming of all sorts… How these spaces, dislocated as photographs immediately become empty stages which all kinds of things can occur.

Mashadi

To end, can we go back to the question of the ‘authorial’, how an artist’s relationship with his viewer is a complicated one? The ‘synoptical’—the invocation of an expansive and general view of things—affords multiplicity of perspectives and readings. To what extent do you regard its limits? I am thinking about One Hundred Years of Solitude, the work that you presented for the Singapore Biennale in 2008. It conflates many things... the original book by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the billboard as a capitalistic expression of imposed desire, and predicaments as currency of negotiation...

Chong

A project that has been on my mind for a long time is to write to all the political ministries around the world that regulate advertising in public spaces, and to propose that they would reserve a certain amount of advertising space for the promotion of novels. While there is no certain quantifiable data that reading novels (at least the ones that are worth reading) makes for a better society, we can all at least agree on the fact that we would have less of half-naked models with unreal bodies in skimpy white underwear to confront.

Essays

“The time frame of four minutes and thirty-three seconds is purely an artificial parameter, so that period of time we can listen and concentrate to the music of the environment which is constantly ongoing, it never ceases and is continually varied. We never listen to the environment; we’re too busy listening to the thoughts in our head.” –Margaret Leng Tan, Singapore GaGa

For historians, echo provides yet another take on the process of establishing identity by raising the issues of the distinction between the original sound and its resonances and the role of time in the distortions heard. Where does an identity originate? Does the sound issue forth from past to present, or do answering calls echo to the present from the past? If we are not the source of the sound, how can we locate that source? If all we have is the echo, can we ever discern the original? Is there any point in trying, or can we be content with thinking about identity as a series of repeated transformations? –Joan Scott, “Fantasy Echo: History and the Construction of Identity”

Sound Inventory

We take for granted that smell is a powerful trigger of memory, yet what we often forget is that in an ever-changing urban space like Singapore, smell is elusive and impossible to record. Demolishing old buildings, old spaces, and natural spaces means that these smells are gone for good—to be replaced with smells of new paint, new concrete, new carpet, and regulated temperature-controlled environments. Sounds though, sounds can be preserved, and these sounds become echoes when digitally recorded standing in for a very bodily memory of space. After all, sound is how our city touches us, touches our body by making our very insides vibrate. From the oscillation of our eardrums, to the pounding in our chests and the ringing that remains in our skulls, sound is by definition a corporeal experience.

Tan Pin Pin’s Singapore GaGa is mostly concerned with city sounds of a subtler nature: busker songs that wind their way around our hearts, the cacophony of footsteps in an underpass, the specific hollow echoes of void decks and an eclectic range of songs that reflect the city’s polygot, cosmopolitan, postcolonial nature. Re-watching the film is letting the city caress you all over again, but with the sad awareness that even filmed only nine years ago, Tan’s film is already a dated, historical document. Her insistence on our focus on the aural however, makes for a particularly visceral nostalgia—although it also begs a few questions: what does it mean to be touched by an echo of a past Singapore? And can an echo ever really replace what is lost, or is it, as the theorist Joan Scott suggests, a repetition which “constitutes alteration… the echo [which] undermines the notion of enduring sameness that often attaches to identity” (291)? Is it somehow, radically, even more than the material reality that initially produced it? Every time someone watches Singapore GaGa, sitting through its fifty-five minutes of contemplative, non-narrative musings, we pay tribute yet again to our complicated histories and listen better for their echoes in the spaces in our city.

Since Tan’s film, there have been many other attempts at reclaiming the complexity and sociality of Singapore’s spaces. Aside from Tan’s own work Invisible City (2007), as a scholar of literature, I find I often turn to Tan Shzr Ee’s genre-bending book Lost Roads: Singapore (2006) as a way of re-experiencing the city as:

a scrapbook—of real and imagined experiences; of half-remembered stories from family, friends and strangers; of interrupted memories; of anecdotes disengaging and dysfunctional; of rabidly untrue rumours; of bizarre signs and notices spotted in unremarkable corners; of overheard conversations and useless laundry lists… throwaway epiphanies that have presented themselves in the course of my travels through ulu1 Singapore. (10)

It is this unpredictable inventory of unverified stories, truncated memories and minute throwaway details that disrupt the orderly, conformist and capitalist spaces of the city. These spaces are resolutely not for profit, whether they are sacred, natural, domestic, fictional, or an unwieldly combination of the above. Tan Shzr Ee’s invocation of them can be seen as a tactic in the de Certeausian sense, and Tan Pin Pin’s modus operandi is similar. Both writer and documentary-maker then, inscribe in their work the power to at least temporarily resist the over-planned and over-determined nature of Singapore. While Singapore GaGa is ostensibly a documentary, it latches on to the similarly random, fragmented and unremarkable—“throwaway epiphanies”. Tan Pin Pin’s use of editing techniques also plays with the temporal nature of sound, silence and memory, often holding on to empty frames and pauses to create a contemplative rhythm that is sorely missing in Singapore’s cityscapes. The medium of Singapore GaGa however, means that we physically re-experience this urban inventory with each viewing. In fact, Tan’s curation of these echoes is such that we might even begin to experience city sounds differently after watching her work—perhaps pushing us to a more intimate conception of our city.

What makes the film’s polyphony so powerful is its eschewing of any grand narrative to describe a city-state whose officials are so obsessed with its teleological progress. Indeed, Tan deliberately creates a cognitive dissonance between the official state narrative and everyday life by overlaying the artificial performance of summiting a mountain (complete with patriotic song soundtrack and fake inflatable mountain) during the annual National Day celebrations with the lonely song of a busker plying his trade in an impersonal covered walkway.

This is not to say that there are no narratives in Tan’s work—there are in fact, one might argue, incredibly important ones. And they are all the more significant for having been hidden, forgotten or just ignored in plain sight for so long. On a meta-filmic level, Tan refuses to impose any overarching moral or message to Singapore GaGa. This means that these corporeal echoes stitched together by her work, leave both the stories and the viewers themselves to find a more complex and nuanced meaning in what it means to make echoes in Singapore’s spaces. This is an ongoing phenomenon, since, as Singapore GaGa demonstrates, what we think of as the present is always becoming the past.