VOLUME

ISSUE 10

Tropical Lab

The 2021 issue focuses on studying Tropical Lab.

Artist learning and practicing environments have historically been defined around concepts of an atelier, which is not merely a hosting space but one that embodies practices, conversations, critiques, references, and histories. Contemporary artist learning environments have evolved to encompass found and transitional sites and group gatherings and activities to facilitate continuous learning towards formal and informal pedagogies.

ISSUE 10

2021

Tropical Lab

ISSN : 23154802

Credits

Preface

Prologue

Exhibition

Essays

Epilogue

Artists’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Credits

Preface

Preface

Prologue

Exhibition

Essays

Social Distance

Making a Difference

Epilogue

Artists’ Bios

Artists’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Credits

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy Editor

Anmari Van Nieuwenhove

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Editorial Board

Professor Patrick Flores, University of the Philippines

Dr. Peter Hill, Artist and Adjunct Professor, RMIT University, Melbourne

Professor Janis Jeffries, Goldsmiths, University of London

Dr. Charles Merewether, Art Historian, Independent Researcher, Curator and Scholar

Manager

Sureni Salgadoe

Contributors

Steve Dixon

Peter Hill

Laura Hopes

Charles Merewether

Anca Rujoiu

Ian Woo

The Editors and Editorial Board thank all reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments and feedback to the contributors.

Credits

Preface

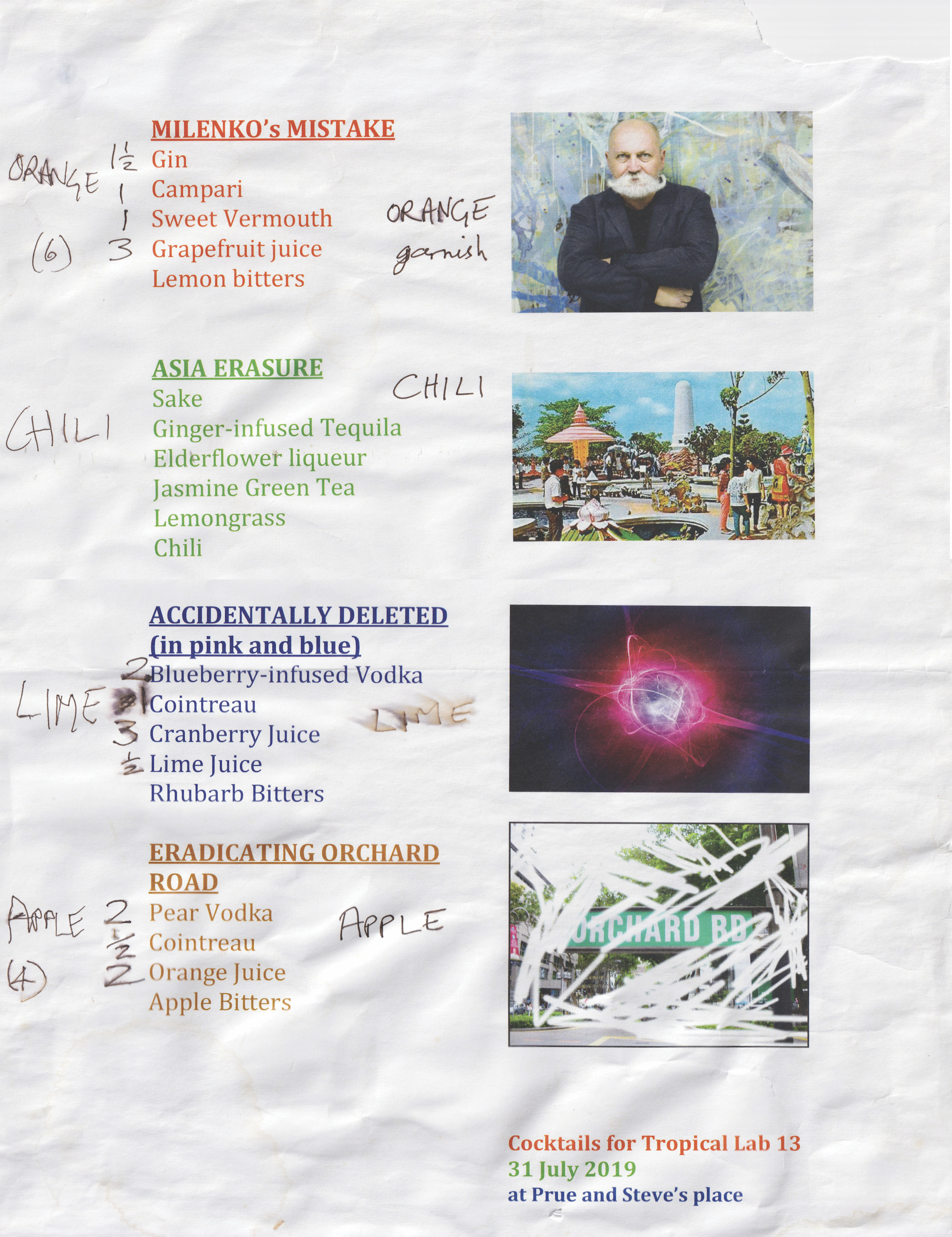

The issue of concern in this volume is Tropical Lab, an experimental initiative of LASALLE College of the Arts in Singapore. An annual residential artist camp, it is inspired by visions of sharing and collaborating over two weeks in the city-state. Brainchild of artist-educator Milenko Prvački, it is an intensive and highly engaging event, bringing together more than 20 student-artists from various internationally renowned art colleges and institutions to engage in a series of workshops, talks and, seminars guided by established international and Singaporean artists. It culminates in an exhibition at LASALLE’s Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore.

The significance of Tropical Lab as a real and imaginative space for student-artists, from different cultural backgrounds to research and experiment, is heightened in a highly neoliberal and mediatised art world. A world that is increasingly being defined by speed over meditation, finality over process, showcase over deliberation, and price over substance. Artists are invited to discover, collaborate and create regardless of medium, method, and approach. As a Lab (artistic, scientific, social, etc.) it becomes an informal pedagogic space with self-developed outcomes. Amidst this experimental lab, new networks and artistic strains ferment.

Essays in ISSUE 10 are carefully curated to bring a range of perspectives to ruminate, appraise, and to reflect on the emerging new world/s of art and artist education through an incisive study of Tropical Lab. Readers will discover that there is an intimacy which the writers bring to Tropical Lab whether as an artist, participant, curator, editor or a college president. This intimacy injects profound self-reflexivity, which lends itself to building a community of advocates who believe in new approaches to artist education. The essays have also benefited tremendously from valuable feedback and thoughtful comments from independent peer-reviewers. Finally, this volume is enriched by an engaging interview with the initiator of Tropical Lab plus an exhibition titled Interdependencies representing its pivot in these pandemic times.

Preface

The issue of concern in this volume is Tropical Lab, an experimental initiative of LASALLE College of the Arts in Singapore. An annual residential artist camp, it is inspired by visions of sharing and collaborating over two weeks in the city-state. Brainchild of artist-educator Milenko Prvački, it is an intensive and highly engaging event, bringing together more than 20 student-artists from various internationally renowned art colleges and institutions to engage in a series of workshops, talks and, seminars guided by established international and Singaporean artists. It culminates in an exhibition at LASALLE’s Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore.

The significance of Tropical Lab as a real and imaginative space for student-artists, from different cultural backgrounds to research and experiment, is heightened in a highly neoliberal and mediatised art world. A world that is increasingly being defined by speed over meditation, finality over process, showcase over deliberation, and price over substance. Artists are invited to discover, collaborate and create regardless of medium, method, and approach. As a Lab (artistic, scientific, social, etc.) it becomes an informal pedagogic space with self-developed outcomes. Amidst this experimental lab, new networks and artistic strains ferment.

Essays in ISSUE 10 are carefully curated to bring a range of perspectives to ruminate, appraise, and to reflect on the emerging new world/s of art and artist education through an incisive study of Tropical Lab. Readers will discover that there is an intimacy which the writers bring to Tropical Lab whether as an artist, participant, curator, editor or a college president. This intimacy injects profound self-reflexivity, which lends itself to building a community of advocates who believe in new approaches to artist education. The essays have also benefited tremendously from valuable feedback and thoughtful comments from independent peer-reviewers. Finally, this volume is enriched by an engaging interview with the initiator of Tropical Lab plus an exhibition titled Interdependencies representing its pivot in these pandemic times.

Prologue

Introduction

Throughout time, artists have expressed an understanding of the world and the immediacy of their lives through travel. The wandering journeys of artists shape the way the world of art is imagined, for they wander beyond physical movement: they wander existentially. A portion of the title ‘wandering journeys’ inherits a contradiction. Wandering presumes, to a degree, aimless meandering, while a journey is destined to a place or space. Together, they enunciate a dialectic: the artist as an observer and participant of the everyday traversing both spatial and temporal geographies. In some ways, travel enables them to work outside the rational arrangement of institutions as formalised enterprises. Perhaps there is an inner rebellion. To work with institutions and yet not within them is wrought with paradoxes. Travel shapes what artists may become, reaffirming an oft-forgotten principle that art is more than mere visual expression. It is a continuous search for a language to express one’s being. While the current condition to travel is vested in social and digital media, at different stages of their travel, artists arrive and depart, enter and exit. They do so to pause and to meet like-minded artists. In situ, they learn, explore and deliberate.

The enabling of travel and congregation was seeded through art schools and academies in the last century to inform artist-learning through casual and informal gatherings as conducive zones of free expression and creativity. It was a fundamental place to hone one’s criticality and bolster the kinds of stories they wanted told. However, contemporary expressions of travel and congregation are no longer exclusive to arts schools and academies as they have been abundantly embedded within museums, biennales and galleries and as competitive residencies and fellowships to support a growing investment in art. Amidst this broad sweep of a transformation, what kinds of new points of inquiry emerge for the artist? This essay muses on some possibilities through the study of Tropical Lab in Singapore.

Arts Schools

We know what we are but know not what we may be.

– Hamlet, Act 4 Scene 5, William Shakespeare

Arts schools1 were founded on the belief that art transforms the individual, the community and society, thereby contributing to a civic and national consciousness. This is located within an Anglo-European philosophy of self-determination and self-realisation expressed most pronouncedly by the philosophical renditions of Êcole des Beaux-Arts (Paris), Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Antwerp) and the Staatliches Bauhaus (Weimar). Across the Atlantic from Europe, named art institutions were established by individual philanthropic, business and educational magnets (Pratt, CalArts, Parsons, etc.), to blend visual and graphic arts to support a fast industrialising America that was responding to a new zeitgeist of contemporary expressions.2 Asia and its myriad of artistic and creative traditions built the arts around craft, livelihood and sustainable traditions. From Istanbul to Yogyakarta and Baroda to Xi’an, artistic traditions were custodial to enshrining and preserving cultural practices through loyalty, patronage and kinship-based community systems. Modernity through colonialism, as problematic as it was, swept through Asia, instilling a pivot to artistic traditions centred on creative genius, identity formation and self-representation. Postcolonial societies cautiously embraced the potency of modernity as the rise of industrialisation was fast entrenching systems of governance, education, economy, and ways of living.

Through a sense of independence, a commitment to a philosophy of practice, a dose of maverick potency and rich culture of making and doing, arts schools remain bastions of artist journeys and facilitators of creative congregations presenting a broad menu of learning approaches to suit varied interests. They remain intense and sometimes self-inflicting while unlocking creative potential. Two examples emerge.

The Black Mountain College, USA, founded in the 1930s, is a short-lived yet potent art school. A destination space for nomadic artists who resisted increasing bureaucratisation of art and education, it became a site that birthed a new curriculum focused on interdisciplinary and experimental practices and a deep commitment to making.3 The College functioned for all but 24 years—perhaps it does not matter how long one is around—and ‘graduated’ the likes of choreographer Merce Cunningham, composer John Cage and visual artists Josef Albers, Walter Gropius, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg and Willem de Kooning. Their impact on the avant-garde reverberated throughout the decades and is still felt today.

On the other side of the world, Kala Bhavana (Institute of Fine Arts), founded in 1919, is located in Visva-Bharati University. Founded in the thick of British colonisation of India by the family of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, he led it to significance. Located in a remote hamlet, Shantiniketan, in West Bengal, it became a centre for thinking through a postcolonial India. It was critical to formulating a pan-national identity through an innovative new curriculum. The institution resisted the dictate of colonial education and fostered the belief that “education should not be dissociated from life.”4 Economics Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, an alumnus of the school, expressly shares that “the emphasis here was on self-motivation rather than on discipline, and on fostering intellectual curiosity rather than competitive excellence” and that artists worldwide, particularly from China, Japan and the Middle East, travelled, resided, taught and created works, studied with faculty and explored new ideas.5 World-renowned Chinese ink painter Xu Beihong was one of the first visiting artists to Kala Bhavana in the late 1930s to explore a new way of thinking about art through transnational exchanges.6 The work of teaching faculty and graduates of Kala Bhavana continues to influence how transnational ideas should be central to the curriculum. These include 20th-century luminaries: visual artists Nandalal Bose, K.G. Subramanyam, Jogen Chowdhury, Ramkinkar Baij, film-maker Satyajit Ray and art historian Stella Kramrisch.

The two examples above were built upon the belief that artist learning points are dissimilar to conventional science, technology, engineering and mathematics, which builds a seamless progression of acquisitive information, synthesis and application to create an impact on society. However, modernity’s cruel play on arts education, predicated on this scientific and universal mode of learning, formalised artists’ continuous inquiry into modern-day lifelong learning and creative output into learning outcomes. Despite this, arts and artist education continued its transformation well into the 1990s. Artists’ learning points do not progress seamlessly and sequentially but rather through a series of dense and, at times, spontaneous, informal and hybridised experiences with technique and technical skills, material study, exhibition-making, residencies, negotiated situations, walking, observing, recording, critiques, explorations and deductive applications, inquiries and post-inquiries and conversing and storytelling—all leading to developing visual diaries of new languages, practices and ideas informing art.

The rapid decolonisation of the world in the early part of the 20th century left vulnerable postcolonial societies exposed to the unfettered globalisation of their economies, cultures and systems. This bolstered the professionalisation of the arts and broadened the scope of art beyond its essential and intrinsic qualities, requiring it to extrapolate itself into another order—the marketplace.7 Art, hyper-extended off artists, became custodial concerns of collectors, galleries, curators and events; and, even tradeable through crypto art-financing schemes.

Globalisation is a double-edged sword: a contracted artist experience is also amplified with a myriad of new opportunities in fields far beyond self-realisation. Art in the contemporary world is here to stay and is all-encompassing, masterfully permeating through the everyday lives of people. The knowledge base of an emerging artist today is much broader in scope, and s/he has a deeper understanding of the economic spheres within which art finds itself. Yet, if globalisation has rendered artists speechless of their informal and experiential approaches, the arts school then becomes the enclave for them to wrest an alphabet just as a speechless Lavinia in Titus Andronicus sought to outline the violence inflicted on her.8 The arts school becomes a research and development site for the production and circulation of new beginnings and meanings while tapping on the new opportunities of the marketplace. Ute Meta Bauer cautiously opines: “Can you discuss the meaning of artistic production within the larger field of culture, or perhaps more precisely, debate what is culture today in such a globally expanded field of experience and how art schools have adapted to this fact?”9 The reality calls for the co-existence of the market (which could potentially determine aesthetics) and the arts school, which continues to drive the discursive meaning-making sphere where the debate is centred.

In an increasingly complex and highly-networked global environment that requires essential artist skills such as exploration, experimentation and self-discovery, the arts school has had to confront the bureaucratisation of arts education and deal with demands alien to its aesthetic considerations. This is not easy and has forced artists to move out of their studio, move around and rediscover. Gielen views, “mobility and networking are today part of the art world’s doctrine,” requiring artists to disembody from the comforts of their studios to discover and create new networks.10 As a community of artists evolves into a community of artist-scholars, artist-educators and artist-researchers, the arts school of the 21st century is also challenged by practical notions of self-sustainability and employability racing the artist from studio to gallery wall.11 In response to the bureaucratisation of arts education, self-organised artist residencies, camps and inter/national exchanges have proliferated throughout the world built around collectivism, shared concerns and spaces to create.12

As the dictates of employability and access beckon the sustainable future of artist education, creative cities, as a feature of globalisation emerge. Cities, imbued with a rich portfolio of infrastructures from galleries, museums to performance venues, serve as cultural meeting points with a plethora of events for domestic and international workers and visitors. Arts schools, on the other hand, while sustaining themselves as a mainstay of thought, ideas and creative processes have become an important—almost crucial—talent pipeline for the creative city. Supporting a creative city and living in it are two different ideas. In an attempt to bridge liveability (quantitative and accountable) and art (qualitative and experiential), recent globalisation policy discourses have shifted to creative placemaking. As opportune as it may be, arts schools followed suit. Arts schools either moved away from remote rural and suburban sites and relocated to city centre or became infused into the city’s downtown core (e.g. School of Visual Arts, New York; School of Art Institute of Chicago; Central Saint Martins, London; and LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore). They became intertwined into the ‘soft real estate’ providing vital sustenance to energise the city. While aiding artist education to remain grounded and global and hold vigil to the varied approaches to artistic curricula, artist camps and residencies emerged as responses to creative placemaking. Here, artists no longer had a quiet meditate residency but needed to engage with a pulsating city.

Lab Notes: Informal Pedagogies and Practices

Through others, we become ourselves.

– Lev S. Vygotsky13

Earlier I outlined dynamic, non-sequential and hybrid learning approaches of artists, much of which remains informal and self-directed. In a hyper advancing world where creativity is challenged to produce material outcomes, artist camps and residencies have become havens to articulate such nuanced methods of inquiry. But art practices play with ambivalence. They co-opt modernity’s scientific and universal forms of education and globalisation’s creative placemaking into their ambit and even risk being an apologist for venturing into the art marketplace without any sand to their elbows. For art is agnostic to all learning approaches and chooses to co-exist and hybridise the space of others. Arts schools are not friend or foe to the marketplace, to modernity’s pedagogy or globalisation’s interests—for art is not. It is in this context that an arts school organises an annual artist camp in Southeast Asia.

Tropical Lab14 is an art camp organised in an arts school located in the city-state of Singapore, known for its free trade and free movement of multicultural communities over the centuries. It pays homage to the equatorial nature of the island’s location: a sleeve north of the equator. The punishing heat and suffocating humidity of the tropics and the shimmering economic wealth of the city-state form a central backdrop to the art camp. Annually, over two weeks, 20 to 25 selected participants15 gather in Singapore to deliberate on a theme of the day.16 The approach is technically simple but conceptually complex. The participants are practising artists enrolled or recently graduated from school, generally at the MA/MFA and even PhD level. They have a substantial body of emerging work and a keen sense of the world around them. They are nominated by their respective institutions upon an open call. Each institution can only nominate one participant, sometimes but rarely two, through various internal systems of pre-selection in which the organiser does not participate. Nominations are sent to Singapore for consideration. Selected participants pay a small participation fee while the organisers subsidise participants from the Global South countries. This is key to ensuring a culturally diverse set of artistic practices and learned pedagogies are afforded to presence themselves amidst more dominant methods of artistic traditions and learned pedagogies as valid and appropriate. Participants have to primarily self-fund their travel, while food, accommodation, art materials and local transport are covered by the organiser for the two weeks. They are also provided free studio spaces.

Participants come from all over the world from a range of institutions, and in studying their profiles, they tend to be culturally diverse even in their home institutions. For example, past participants include a Mongolian studying in the USA, a Palestinian studying in Europe and an Australian studying in Vietnam. This transnational diversity is significantly pronounced in the arts school environment, reinforcing my opening remarks regarding the artists’ proclivity to traverse spaces and places. While the English language is the primary mode of communication in Tropical Lab, participants bring a rich plethora of formal languages of their cultures, enriching the camp.

Tropical Lab is organised in three interwoven yet parallel tracks that converge: sharing, learning and making.

Sharing entails two parts: A curated one-day seminar comprising papers and talks by invited artists, curators, architects, performers, theorists, scholars, art historians, researchers, etc., laying the ground for exploring the theme of that particular edition of Tropical Lab. It is also an opportune moment to understand the camp’s location and the mental, creative and philosophical space within which the participants will work. Following the seminar, an intense sharing of each participants’ art practice and creative journey ensues. Part autobiographical and part visual diary, it reveals the deeply held principles, concerns and convictions each artist has, providing a vital node for connectivity with others through their practice and opportunity to be self-reflexive and learn and unlearn through others.

While learning takes place during the sharing track, learning as lived experience is organised through site visits to various types of urban, suburban and rural spaces, events and exhibitions, artist studios and gastronomic explorations. Tropical Lab takes place in LASALLE’s McNally campus, a futuristic modernist architectural building notably contrasted by its location. The campus, located in the heart of the arts and civic district bordering downtown’s fringe, is nested centrally amid living and functioning cultural and heritage districts, Little India, Chinatown, Kampong Glam, Armenian and Jewish centres. A confluence of multiculturalism confronts the participants as they attempt to steal a conversation between the futuristic building and the heritage districts. Adding to this layer is the introduction of food. Food is akin to ‘welcome’ in Southeast Asia, but more importantly, a means to build an esprit de corps amongst the participants. Each lunch and dinner is carefully curated to provide a complete cultural arch. To learn about food is just as important as consuming it. For instance, food as a tool of affect, particularly in Southeast Asia, stands for hospitality, care and fellowship. The participants undergo a sensory assault of art, culture and heritage, urging them not to merely collect and centralise their learning to themselves but to dis-member their learned experiences from an economy of artistic centralisation to become one with others to learn as a community.

Finally, making. The artist studio that each participant is allocated is a shared space for participants to create their response to the theme. They are encouraged, but often self-motivated, to develop a work or body of work to be individually showcased in an exhibition. The creative process confronts the Lab environment as the making unravels in full view of others. The participants work through all they have collected and experienced, unpacking objects, sites, scenes—photographed, scribbled, and etched in the mind and social media. The intensity of making for these confident artists can be bewildering as they attempt to disassociate their presence as cultural tourists into a distinctive embodied self, located in a different time, place and space. The participants are provided with a modest material fee and have the opportunity to access the college’s workshops and equipment where needed. The works range far and wide in method, material and discourse, underscoring Tropical Lab’s agnosticism to artmaking processes. In the artist studio, works-in-progress are sighted and critiqued and curated by the director of The Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore (ICAS) into a consummate public finale. The exhibition opens at the end of the camp at the ICAS’ main galleries, just as the artists pack and depart. Some travel home, some stay longer in Singapore, some commence an exploration of Southeast Asia. It marks the beginning of a new connected artist collective, a tribe.

Tropical Lab may seem an oasis of informality. However, in unpacking its approach, it is both intense and dense and differs substantively from other residencies and art camps. Instead of taking the most common route of providing studio space and leaving artists to their own trajectories, here the juxtaposition of sharing, learning and making within a period of dislocation, with limited time to scope the living environment, is challenging and life-altering. This is especially so when the participating

artists work within a series of mandates: an exhibitory mandate to create and display; a social mandate to gather, socialise and explore facets of a city-state; a cultural mandate to learn the multicultural dimensions of Singaporean society; a critical mandate to unpack past learned practices and perspectives (theoretical, historical or technical) to formulate the new; and, a personal mandate to see and be different. These mandates form the basis for an emerging community of practice, informed by listening and visualising through others and being subjected to extreme scrutiny by others. There is a danger that superficiality or fetishisation of the overall experience can reign supreme, especially when time is of the essence. As such, preconceived ideas and predetermined approaches are kept in check at Tropical Lab through detailed, almost forensic, conversations. Commencing with a sense of informality, the participants soon realise the profound structural opportunities Tropical Lab affords as they are provided with extraordinary access to subject-specific lecturers and tutors to deliberate their findings and impressions.

Sarongs, Gotong-Royong, and New Initiatives

At some point in the two weeks in Singapore, participants receive a sarong—a piece of tubular gender-neutral stitched fabric worn at the waist in Southeast Asia. It is a very affordable daily wear piece that is friendly to the hot and humid weather of the region. The fabric is called many different names, and its manifold manifestations can be seen throughout Asia, Africa and the Pacific islands. The sarong is synonymous with ikat and batik prints17 and motifs. It bears multiple uses from keeping one modestly covered, keeping warm, cradling a child, carrying goods and many others. Its use-value translates into a signifier of collaboration as traditional communities weave and create together. Collaboration in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore and the larger hinterland is known as gotong-royong. It is a participatory strategy that helps individuals and communities to collaborate and help one another. It is an instinctual and existential practice, much of it blurred in the overt valorisation of individual subjectivity in modern society. Collaborations are as much work as fun. Each passing day is configured with activities and movement. It is exhausting and sober but elegantly punctuated with meals transforming into a bounty of joy, humour and discoveries. Here the individual emerges to just being, as conversations are re-rendered, becoming leitmotifs of oral histories. This is a feature of gotong-royong, which foregrounds horizontal alignments between communities and people—creating fluid movement between ideas, identities and experiences through conversations heard and overheard as they continuously open their borders to invite outsiders from within and without.18

Gotong-royong for the participants can relieve them of their anxieties around the demand to produce art. It facilitates them to explore and dispense with the centrality of their subjectivity collectively. Ultimately, though participants have collective experiences, they produce individual responses which differs markedly from their taught practices from school, as described by the volume of past participants. Many seek to return to Tropical Lab to recalibrate themselves. It would be possible to read this need to return on two fronts. First, it is a manner of recounting the experience within a congregational framework of folkloric tales, legends, art and anecdotes (e.g. the Tropical King19), thereby building a tradition around Tropical Lab. It is a romantic idea—one that dangerously skirts around nostalgia and novelty antithetical to the Lab’s intent to bring new and diverse individuals together. Alternatively, it could be read as the emancipated artist’s mind desirous of furthering its repertoire of experiences through renewed participatory activities, inquiries and a sheer desire to meet others. Both remain valid as they speak to the formalisation of that which is informal and experiential.

Some manner of formal activities did emerge. Tropical Lab birthed two new initiatives in the spirit of sharing community practices: Baby Tropical Lab and ISSUE. Baby Tropical Lab takes each year’s central theme. It develops into a one-week workshop for high school students across Singapore and their art teachers to explore art-making processes through collaborations across schools. Running it for more than five years has brought about students’ understanding of resourcefulness and resilience and the artist journey, as evidenced by the annual feedback from the participants. Secondly, in preparing participants to come into the Tropical Lab proper, pre-reading material was provided since 2005. These pre-reading materials melded with the seminar proceedings to become a reflexive, peer-reviewed art journal ISSUE since 2010.20 These have become anchors to this global camp.

It is essential to recall why Tropical Lab warrants study. Its approach to intensive study through informal practices and collaboration is transformational. It awaits scrutiny as a dissertation and now, at best, serves to be a prolegomenon on informal arts pedagogies and practices. While it awaits its turn, it remains of interest to the intrepid artist on a continuous search to emancipate, innovate, diversify ideas, and one who is outright curious.

Footnotes

1 I have pluralised the arts to be encompassing of art, design, media and performance as opposed to the ‘art school’ which historically is credited to fine arts

2 Madoff, Art School: Proposition for the 21st Century

3 Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College

4 Visva-Bharati, Annual Report, 2013-2014, 1

5 Sen, The Argumentative Indian, 114-115

6 Xu, “Discovering my Father Xu Beihong’s Experience in Shantiniketan, India.”

7 See Dutta, The Bureaucracy of Beauty, for an incisive study of colonial enterprise and the bureaucratisation of art

8 Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus, Act 3, Scene 2

9 Bauer, “Under Pressure,” 222

10 “Institutional Imagination: Instituting Contemporary Art Minus the Contemporary,” 21

11 Bauer, “Under Pressure,” 221

12 Thorne, School: A Recent History of Self-Organized Art Education

13 Vygotsky, “The genesis of higher mental functions”

14 As an artist-curated endeavour, the term Tropical Lab combines two words: tropical and lab. Tropical may simply refer to the location formed by the interlocking solstices creating the third space at the equator where the meeting point is also a site of change, of a turn, a trope. The second word lab is the short-form of laboratory derived from Latin’s ‘laboratorium’—a place of labour or work (Online Etymology Dictionary, etymonline.com). The principal combination of the two words portents the possibilities of the arts camp. Milenko Prvački, the initiator, says: “I chose the name Tropical Lab because, I did not want Singapore to be just identified as a very developed metropolitan country/island but a sophisticated playground for experimentation and exploration” (Email to author, 8 Nov 2021).

15 With the exception of Tropical Lab 2020, 2021, which pivoted to online/digital showcases in response to the global pandemic, Covid-19.

16 Urban – Non Urban (2005)

City (2008)

Local – Global (2009)

Urban Mythology (2010)

Masak Masak (2011)

Land (2012)

Echo: The Poetics of Translation (2013)

Port of Call (2014)

Island (2015)

Fictive Dreams (2016)

Citation: Déjà vu (2017)

Sense (2018)

Erase (2019)

Mobilities (2020)

Interdependencies (2021)

17 Both ikat and batik are textile dye techniques practised in the Southeast Asian region

18 There has been intense study of collaboration as a means of responding to national and global concerns. A signal of this is in the appointment of Indonesian artist collective, RuangRupa as the curators of Documenta Fifteen in 2022

19 Prvački is eponymously called Tropical King

20 As editor of this journal, I have taken part over the years in several seminars of the Lab, met with participants and overheard conversations between and during meals, celebrated their exhibitions and cheered them on. At each turn, I have become more curious to learn of the many different entry points from which participating artists engage with the theme put forth to them.

References

Bauer, Ute Meta. “Under Pressure.” Art School, edited by Steven Madoff. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009, pp. 220-221.

Dutta, Arindam. The Bureaucracy of Beauty: Design in the Age of its Global Reproducibility. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Gielen, Pascal. “Institutional Imagination: Instituting Contemporary Art Minus the Contemporary.” Institutional Attitudes: Instituting Art in a Flat World, edited by Pascal Gielen. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2013.

Harris, Mary. The Arts at Black Mountain College. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

Madoff, Steven Henry. Art School: Proposition for the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

Sen, Amartya. The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian Culture, History and Identity. London: Penguin, 2006.

Thorne, Sam. School: A Recent History of Self-Organized Art Education. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017.

Visva-Bharati. Annual Report. 2013-2014.

Vygotsky, L. S. “The genesis of higher mental functions.” The history of the development of higher mental functions, edited by R. Reiber, Plennum, 1987, Vol. 4, pp. 97-120.

Xu, Fang Fang. “Discovering my Father Xu Beihong’s Experience in Santiniketan, India.” Institute of Chinese Studies, 2009 (Blogpost: https://icsin.org/blogs/2019/08/13/discovering-my-father-artist-xu-beihongs-experience-in-santiniketan-india/).

Exhibition

Since 2005, art students from universities in Bandung, Belgrade, New York, Plymouth, Tokyo, and so on, meet each other at LASALLE, to work and live together in Singapore as part of Tropical Lab. An experiment in art education, this two-week intensive art camp was initiated by artist Milenko Prvački. In its establishment, Tropical Lab was informed by the artist’s youth experience with art colonies in Tito’s time, art camps functioned as a refuge from political control. They were isolated, mostly in nature, historical locations or monasteries. Artists from Yugoslavia and international artists will be in residence for one to two weeks and communicate, debate, exchange, experience. I did visit many of them in Počitelj, Mileševo, Ečka, Bečej. I was running Deliblatski Pesak.” Milenko Prvački in conversation with the author, September 2021. ']former Yugoslavia.1 Such retreats that Prvački witnessed in his youth share similarities with current artists-in-residence programmes across different geographies. Irrespective of their different models and resources, these initiatives, including Tropical Lab, are driven by common beliefs. Exceptional conditions as in dedicated time, space, and new exchanges with people and places, can play a transformative and long-lasting role in an artist’s practice and fulfil a clear function in an art system. Within the histories of art colonies and artists-in-residence programmes, it is not surprising that Tropical Lab is the result of an artist’s vision. Artists have often taken a leading role in creating conditions for their peers to produce and display art and generate discourse. This understanding that an artist beyond one’s art-making can or should operate at interconnected levels of an art ecology fuelled many of such artists’ initiatives.

In a questionnaire, several artists shared that Tropical Lab made them step out of their comfort zones and broadened their perspectives.2 I can testify to a similar experience curating this survey exhibition of a selection of former participants in the Tropical Lab. When I was invited to embark on this mission, I immediately agreed. I knew that in the nature of a programme such as Tropical Lab that is grounded on exchange, unexpected encounters and connectivities will arise in the process of exhibition-making: encounters that the current pandemic Covid-19 made rare and precious. I was introduced to a diverse group of 25 artists active in the field and selected by Tropical Lab faculty partners.3 While this framework combined with different Covid-19 provisions in the gallery spaces (no use of headphones, for instance) might feel restrictive, it compelled me to return to the basics of exhibition-making. I had to think carefully about the triangulation between space, artwork, and visitors, patterns of access and mobility, material textures, conditions of lighting, all elements that combined together, give an aesthetic form to an exhibition. I was preoccupied with creating the right setting for each work and optimising its relation with the respective location—whether of fusion or contrast. Most importantly, the diversity of existing and new artworks in this exhibition from large-scale paintings, immersive animation, post-minimalist sculpture, wall drawing, interactive augmented reality and so on, not only paid justice to the wide breadth of contemporary art but made me consider diligently the needs of each artwork and the specific experience it entails.

As an exhibition that celebrated 15 editions of Tropical Lab and preceded the launch of a digital archive and ISSUE’s special volume, it asked, I believe, for a moment to ponder on the nature and value of such an artistic exchange. As such, the proposed title Interdependencies was less thematic and more reflective. It captured the spirit of togetherness, peer learning, and cross-pollination that defined all the previous editions of Tropical Lab. In times of antagonistic discussions around identity, it is worth returning to Edward Said’s understanding of culture as a matter of “interdependencies of all kinds among different cultures.”4 Said rejected the assumption of such things as original ideas and indirectly of what has often been coined in relation to non-Western worlds as derivative works. He saw cultures as always permeable, “the result of appropriations and borrowings, common experiences,” a process that has also served expressions of resistance and opposition to dominant structures.

In addition, the notion of ‘interdependencies’ spoke to the current moment. While the pandemic touched our existence in many different ways and hindered off-screen encounters, it made us all acknowledge our interdependencies as fundamental to art and life. There was no expectation in the selection of the artworks or the development of new projects to directly address the pandemic. And it is precisely the absence of a prescriptive approach that made it possible to observe how in manifold ways the pandemic did influence and permeate artistic production creating overall in the exhibition a sense of a collective experience in tune with the planetary unfolding of current events.

Lastly, the concept of interdependencies played an important role in the layout of the exhibition determining juxtapositions and associations between artistic positions and contexts of reference, as well as endowing each gallery space with a distinct mood. Of course, one might argue this is always the case of any group exhibition, in particular those of a larger size. Yet, when artists are brought together for no other reason or agenda than the quality of their practice as was the case of this exhibition, the differences between artworks tend to be less flattened and the usual search for a common denominator becomes of secondary importance. Each artwork occupies a specific position and can serve as a point of departure for a broader discussion.

As curatorial essays or catalogues often precede the completion of the show, exhibition histories tend to be short of accurate documentation. Led by this consciousness and favored by a leeway of time following the installation of the show, I transposed into a spatial transcript for interested readers, a tour of this exhibition as experienced on site by various groups of visitors.

McNally Campus

A key aspect of this exhibition was to highlight the special relationship the artists taking part in the Tropical Lab have had with LASALLE’s McNally campus, which was an integral part of their exchange, learning and artistic production. As such the exhibition stretched in situ across the campus, outside the three galleries: Praxis Space, Project Space, and Brother Joseph McNally. This proposed approach became more convincing during the conversations I conducted with several artists when I was pleasantly surprised that their memories of the campus felt so fresh and vivid even years after their trip to Singapore. In the spirit of interdependence, artworks were integrated within the campus—co-existing with students’ activities and making use of the current infrastructure, such as existing screens.

Inside the College’s Ngee Ann Kongsi Library, one of the two screens (LED TV monitors) that faces the glass entrance, played James Yakimicki’s animated painting; this generated a spontaneous moment of encounter between artwork and passing students (Fig. 1). The cascading effect of the river that cuts through a landscape informed by the artist’s visit to Singapore was amplified by the verticality of the screen. Liu Di’s sleek and speculative digital video was hosted on a 3M screen at the Creative Cube: a multidisciplinary performance space, catching the attention of both students and the general public because of its location facing a public passageway. Imbued with a futuristic imagery, fashion and choreography, the video animated the campus and spoke to the inherent interdisciplinarity and cross-pollinations in an arts college such as LASALLE (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1

James Yakimicki, 2012–RISING FALL ... 2021–CHEWED UP & SPIT OUT(NOTHING MATTERS), 2012/2021,

oil on stretched linen animation by motion leap, 152.4 x 200.66 cm

Fig.2

Liu Di, Pattern, 2020, high-definition digital video, cinema 4D software, 2:00 mins

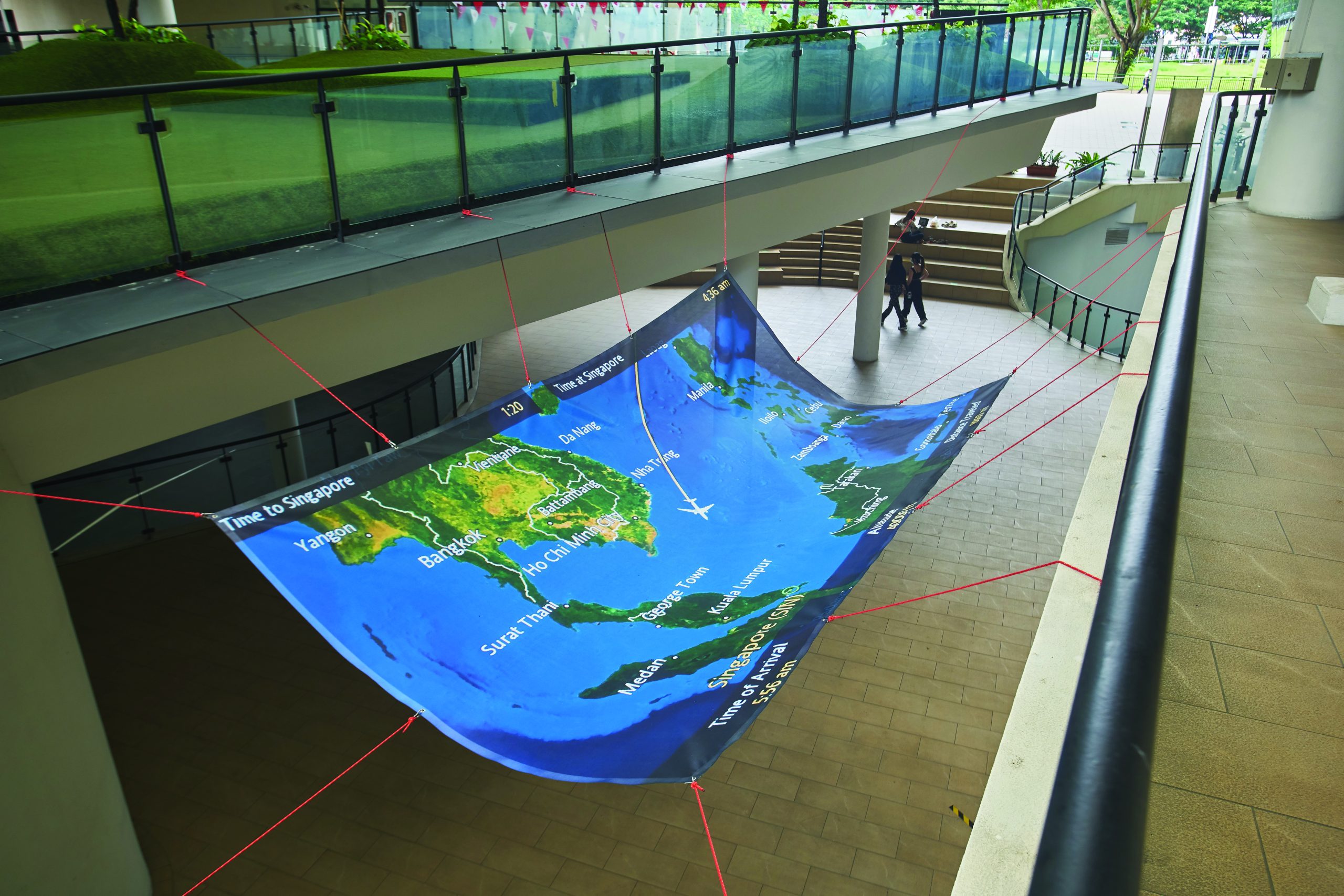

From various points in the campus, one would notice a large piece of tarp levitating above the ground, intermittently shaken by gusts of wind, or beginning to buckle under the force of the rain (Fig. 3). This shelter-like structure was hung outdoors in close proximity of the campus amphitheatre stairs where students often socialise, gather for lunch and meetings. The screengrab printed on the tarp was taken by the artist Duy Hoàng on his trip to Singapore in 2017 at a point when the plane was crossing nearby Nha Trang, the artist’s hometown. This was the closest the artist has been home in the past two decades which made this personal experience, as suggested by the artwork title Perigee, match the intensity and singularity of a celestial event. The suspended tarp conveyed the elusive experience of belonging for those uprooted from “home.”

Snippets of conversation punctuated with visceral and onomatopoeic sounds permeated the immediate surrounding area and became more palpable outside the entrance of Brother Joseph McNally Gallery (Fig. 4). Here the two-channel sound installation by Brooke Stamp in collaboration with performer Brian Fuata was literally suspended in mid-air. The attempt to create a psychic communion in times of isolation and distance took the form of a parallel relay communication between the two artists improvising from their respective locations. The sound flew up, shifting the visitors’ gaze towards the distinctive campus sky bridge. While the bridge served as a metaphor for this experiment, the nonsensical dialogue acknowledged the difficulties, if not the impossibility of communication in these exceptional times. A sound installation of a different nature, this time linear and cohesive, was hosted in an open-access space. In this quiet and secluded space, beside Creative Cube foyer, visitors could eavesdrop on the conversation between the artist B. Neimeth and her 95-year-old grandmother. Their different, often conflicting views on dating life and gender dynamics marked a generation gap that, nevertheless, was softened by the affectional bond between the two women (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3

Duy Hoàng, Perigee, 2021, print on tarpaulin, ropes, 280 x 448 cm

Fig.4

Brooke Stamp in collaboration with Brian Fuata, Psychic Bridge, 2021,

two-channel sound installation, 64:00 mins

Fig.5

B. Neimeth, My little old shrimp woman dried up like a prune, 2021,

two-channel sound installation, 23:55 mins; Erika from the Archive 4, 1946/2018,

archival pigment print photograph, 15.24 x 10.79 cm

Praxis Space

From all three galleries, Praxis Space exuded a contemplative and poetic mood with a constellation of artworks providing a meditation on life, disappearance, and acts of remembrance. Visitors who entered the gallery could step on vinyl showcasing cracks onto the floor (Fig. 6). The work was based on a performance in which the artist Pheng Guan Lee rolled a 700 kg sand and wax ball across a tiled floor that broke during the process. Manipulating the documentation of this past performance into something anew, the artist highlighted that irrespective of technological accuracy and capacity, our memories are malleable and adjustable to fit desired narratives. At the opposite end of the entrance, Homa Shojaie’s video proposed another form of reconstruction (Fig. 7). In an epic effort, the artist presented nine different phases of the moon, by editing frame by frame twenty-five seconds of an original video that captured the reflection of the full moon in a pool of water. A Turkish and a Cantonese pop song with a haunting melody, sounds of barking dogs and rippling water accentuated the nocturnal and sentimental tone of this devotional piece to the moon.

Fig.6

Pheng Guan Lee, The Spin, 2021, digital print, 420 x 170 cm

Fig.7

Homa Shojaie, still from [15931 moons] (Mehr o Mah / Sun and Moon), 2021,

digital video, 4:55 mins. Courtesy the artist

Tim Bailey’s painting on aluminium was in equal manner the result of memories and chance. Informed by the Japanese Zen temple gardens, in particular, Kyoto’s 15 stones sand garden (Ryōan-ji), and shaped by the interaction of materials between the non-absorbent coating aluminium and paint, this work was a reminder that the unknown is an integral part of life. In its close proximity, Ben Dunn’s deceptively simple painting offered a space of observance, an intimate memorial produced in the midst of the pandemic in the United States. Made of wood from diseased trees from forests, the painting’s lower curved shape held a dry pigment as an offering to materials that make art possible. High up on the wall, Rattana Salee’s brass sculpture is a replica of one of the few remaining columns of the abandoned Windsor Palace in Bangkok. Its destruction speaks of the inevitability of disappearance (Fig. 8).

The long wall of Praxis Space faces the outside, benefiting from natural light and subjecting the works on display to daylight fluctuations. Shuo Yin’s diptych produced a confrontational encounter with the viewer (Fig. 9). Blowing up small ID photos over 100 times, the artist conveys the process of othering that many immigrants experience. Through lack of details, the faces become blurred signalling the loss of personhood when one’s existence is continuously reduced to simple identity markers, such as nationality or ethnicity.

Fig.8

From LEFT to RIGHT

Homa Shojaie, [15931 moons] (Mehr o Mah / Sun and Moon), 2021, digital video;

Tim Bailey, Yellah (stones), 2021, oil and varnish on coated aluminium, 150 x 100 cm;

Ben Dunn, Untitled, 2020, wood and pigment, 51 x 42.4 x 3.9 cm;

Rattana Salee, Old Column, 2017, brass, 36 x 36 x 46 cm

Fig.9

Shuo Yin, WA and CA, 2020, oil on canvas, 231 x 259 cm

Fig.10

From LEFT to RIGHT

James Jack, Ghosts of Khayalan, 2021, natural pigments, wax on wall, dimensions variable;

Ali Van, The Mandarins, 2020–21, glass, old fruit, blood, breath, moon, 2010-x, dimensions variable

Created in situ, James Jack’s drawing on the wall was a visual diagram of the artist’s long-term research on Khayalan Island understood as a realm of imagination (Fig. 10). Taking the shape of a fishing net, the drawing generated kinships and preserved memories between people, places, stories, objects convened in this research. An integral part of this entanglement were the drawing’s colours produced out of local pigments from different parts of Singapore: Pulau Hantu (Keppel), Queenstown, Redhill and Jalan Bahar, respectively. Keeping this wall drawing company, on a low standing platform that allowed for closer inspection, Ali Van’s mesmerising and fragile glass orbs containing different organic materials lay: withered flowers, dry mandarins, ashes, menstrual fluid (Fig. 11). Each orb is a capsule of time, the artist’s idiosyncratic diary.

Fig.11

Ali Van, The Mandarins, 2010-x, glass, old fruit, blood, breath, moon, dimensions variable

Brother Joseph McNally Gallery

A constellation of artworks that tested the possibilities of sculpture or responded to climate crisis and colonial histories defined this gallery. Sarah Walker’s video directly faced the visitors entering Brother Joseph McNally Gallery (Fig.12). The visitors became, as with the subjects in her film, witnesses to something unknown—a disaster perhaps that faded slowly into the background.

Fig.12

From LEFT to RIGHT

Waret Khunacharoensap, Who is Sacrificing? 2021, print on canvas, 60 x 100 cm;

Tromarama, Stranger, 2021, 3D printed resin and artwork from LASALLE College of the Arts Collection, Institute of

Contemporary Arts Singapore, unknown artist and unknown production year, both 70.5 x 15.5 x 15.5 cm;

Anne-Laure Franchette, Travaux Temporaires (Temporary Works), 2021, plywood and paint, 104 x 58.5 x 170 cm;

Sarah Walker, Ado (Pillar of Salt), 2019, high-definition digital video, 15:00 mins

Fig.13

Tromarama, Stranger, 3D printed resin 70.5 x 15.5 x 15.5 cm

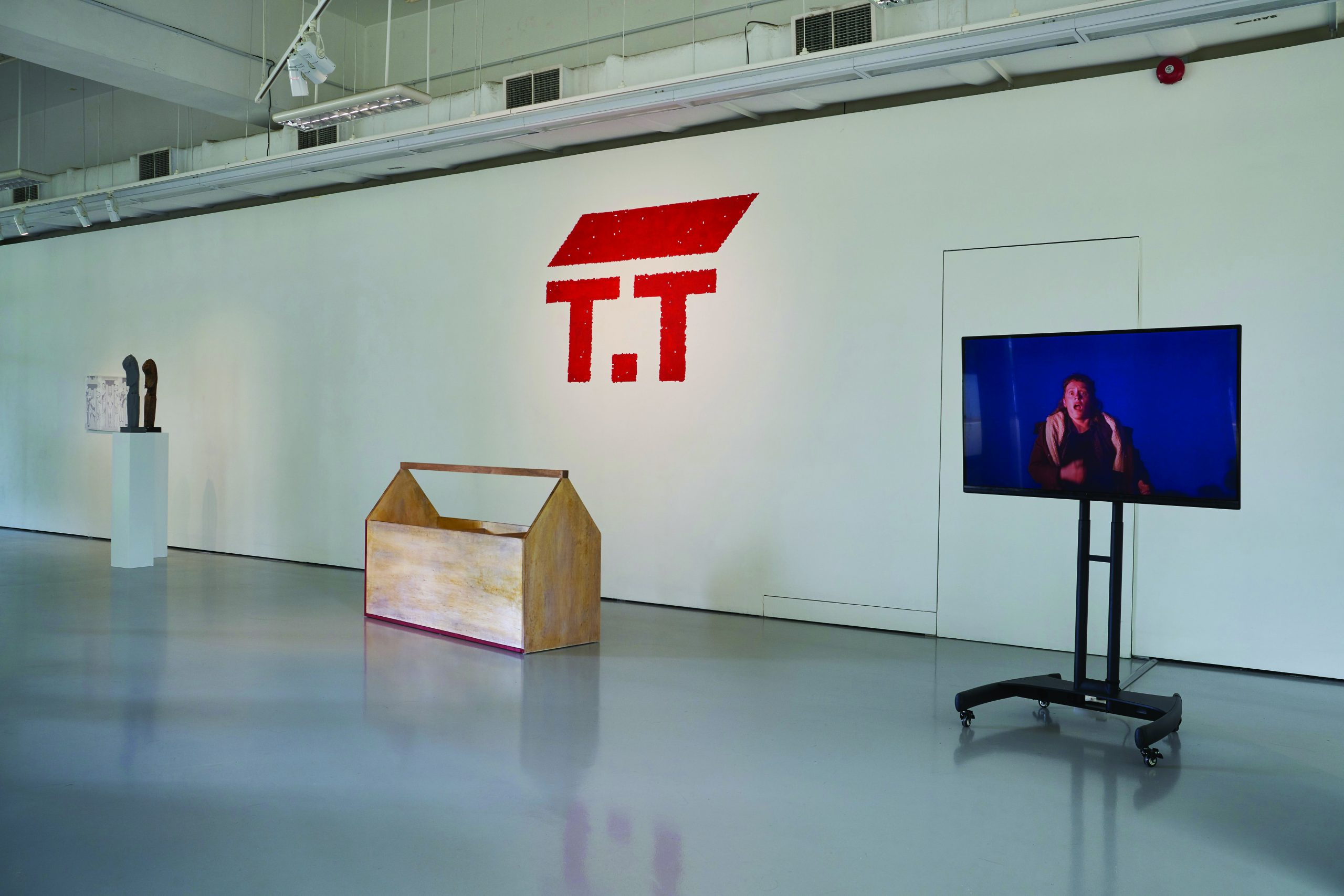

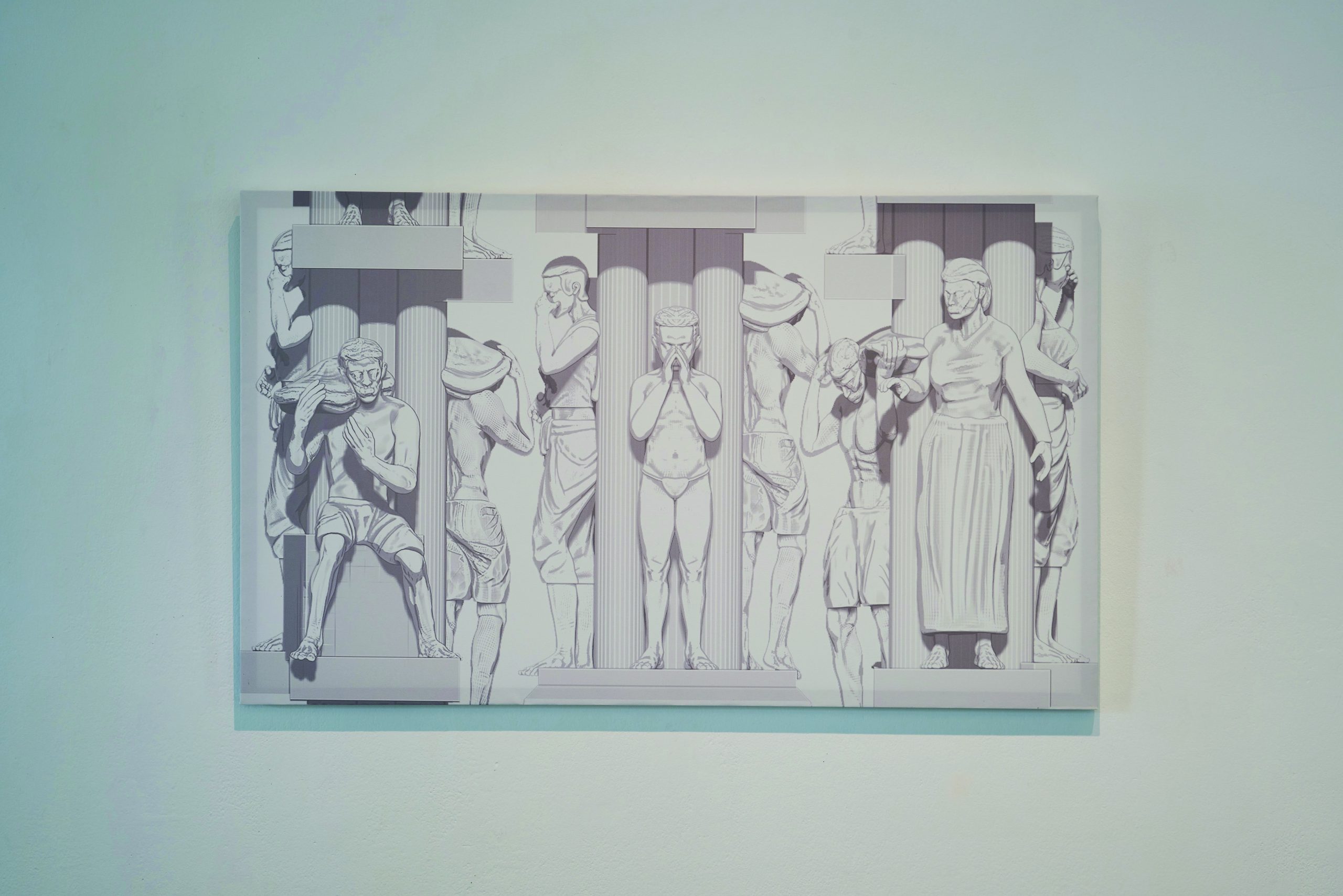

Moving further into the gallery, visitors encountered different approaches to the medium of sculpture. Anne-Laure Franchette investigates vernacular objects built by workers out of leftover materials on construction sites in the post-industrial Swiss city Winterthur. The toolbox in the exhibition was an enlarged replica of one of the transitory structures, a toolbox alongside the painted logo T.T (Travaux Temporaires/Temporary Works), that stands for artist’s archive of DIY built structures, tools and materials (Fig. 12). The Bandung trio, Tromarama, were intrigued by an enigmatic work from the LASALLE’s collection, a wooden statuette depicting a figure. There is no information recorded in the collection about the author of this work and its year of production. Despite the questionable provenance and its impact on the value of this artwork, the artists put the sculpture under the spotlight. Not only did they display it in the exhibition but they had also created a faithful reproduction with the use of 3D printing that sat next to the “original” (Fig. 13). Waret Khunacharoensap’s print on canvas was a representation of a fictional public monument (Fig. 14). Who is sacrificing? asks the artist, essentially questioning how Thai monarchy reinforces certain myths through the manipulation of its public image.

Fig.14

Waret Khunacharoensap, Who is Sacrificing? print on canvas, 60 x 100 cm

Fig.15

Marko Stankovic, 2020, 2021, glass, plywood, aluminium, 200 x 220 cm and 40 x 79 x 79 cm

Marko Stankovic’s new sculpture was a personal response to the unfolding of events in 2020 in the formal language of postminimalism (Fig. 15). Endowed with design qualities, the sculpture blended in with the wider campus architecture. Set against the built campus environment was the abstracted landscape of Cornwall’s coastline landscape explored in Laura Hopes’ video (Fig. 16). The area captured by the artist is well-known for deposits of what has been coined “china clay” or kaolin. Since its discovery in the 18th century, it has led to the development of a global porcelain industry.

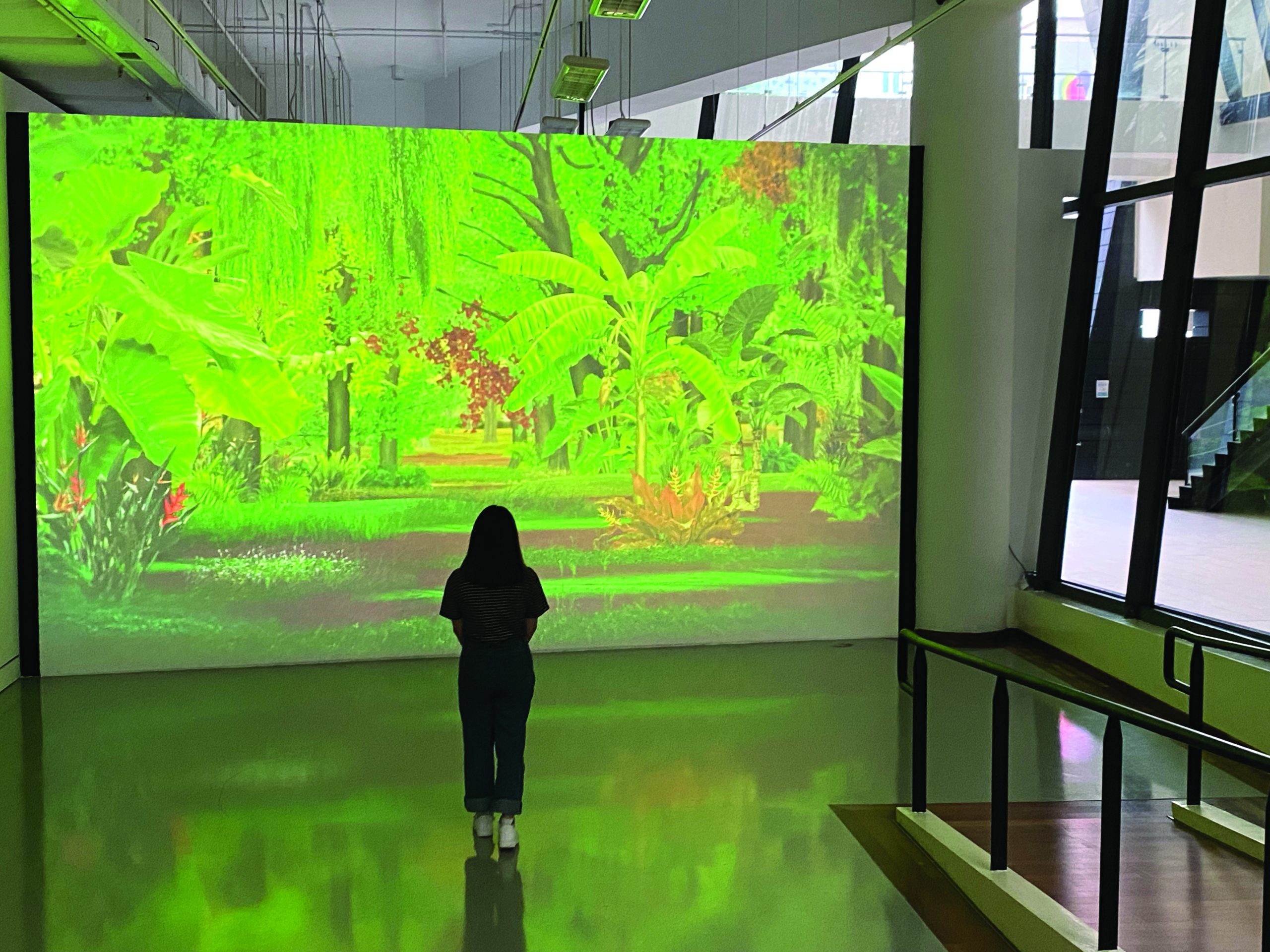

Fig.16

Laura Hopes, Lacuna: Colour of Distance, 2016, high-definition digital video, 4:54 mins

Fig.17

Danielle Dean, Private Road, 2020, high-definition digital video, 4:00 mins

Danielle Dean’s seductive and deceptive animation, added another perspective on environmental exploitation and gave an impactful aesthetic form to a political narrative. From a picturesque image of the North American forest captured in a 1965 Ford Lincoln “Continental” print ad, the artist ‘drove’ the viewers further and further into the forest that morphs into a tropical rainforest akin to the Brazilian Amazon. This seamless transition highlighted the invisible ramifications of multinationals and their exploitation of resources (Fig. 17). James Tapsell-Kururangi’s discrete stack of posters on the floor was a gesture of resistance and position towards the pressure of high-productivity and its colonial undertones that the artist apprehended during his visit to Singapore. (Fig. 18) The statement in the poster gave voice to contestations and frictions that are inherent in any cultural exchange.

Fig.18

James Tapsell-Kururangi, Untitled, 2021, text, 42 x 29.7 cm. Courtesy the artist

Project Space

Project Space was tuned to a more alert rhythm. Set next to each other, two artworks produced between two distant cities, Brooklyn and Jakarta, transposed the shared experience of isolation as brought on by the pandemic. j.p.mot Jean-Pierre Abdelrohman Mot Chen Hadj-Yakop reproduced the experience of confinement in an augmented reality app made using the ceiling of his studio, photogrammetric capture, and blue corn tortillas (Fig. 19). Echoing all the video calls (which were normalised during the pandemic), this augmented reality app defied physical boundaries and teleported the artist into the gallery space. Hariyo Seno Agus Subagyo’s video directly captured the experience of alienation and social isolation produced by Covid-19 in Jakarta (Fig. 20).

Fig.19

j.p.mot Jean-Pierre Abdelrohman Mot Chen Hadj Yakop, I love hummus, 2020,

Augmented Reality app and Maxon Mills Ceiling RM.6, [41.8058° N, 73.5606° W], print, 111.76 x 88.9 cm

Fig.20

Hariyo Seno Agus Subagyo, Alienation, 2021, digital video, 1:31 mins

Fig.21

Kay Mei Ling Beadman, Dress Coded, 2021, 5 photographs, 87.5 x 58.4 cm. Photographs by Lin Jun Lin

Two other works in this gallery were grounded on biography. Drawing on her Chinese and white English mixed-race identity, Kay Mei Ling Beadman’s work is an inquiry into the complexities of identity formation and constructed racial hierarchies. The silver and golden metallic cloaks in the five performative photographs are markers of identity that question the problematic ideas of the 19th-century treatise Datong Shu by Kang You Wei. Despite progressive political views, the scholar proposed a eugenic super race of Chinese and white mixedness (Fig 21). Christine Rebet’s jarring animation delved into the psyche of her father, a former soldier who fought in the Algerian war. The war which unfolded between 1954-1962 was well-known for its guerrilla warfare and acts of torture. Disrupted figurative imagery, splashes of colour and piercing sounds translated for the screen the trauma of the war (Fig. 22).

Fig.22

Christine Rebet, In the Soldier’s Head, 2015, animation, ink on paper, 4:24 mins

The tour ended or could start right here.

Unless otherwise stated, all images courtesy LASALLE College of the Arts

Thank you to the artists and everyone who made this exhibition possible:

Tropical Lab:

Milenko Prvački, Founder and Senior Fellow, Office of the President

Sureni Salgadoe, (Projects), Office of the President

The Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore (ICAS):

Ramesh Narayanan, Manager (Operations)

Mohammed Redzuan Bin Zemmy, Executive (Exhibitions)

Sufian Samsiyar, Senior Executive (Exhibitions)

Production (new works):

Jezlyn Tan, Project Manager, Circus Projects

Footnotes

1 “During [Josip Broz] Tito’s time, art camps functioned as a refuge from political control. They were isolated, mostly in nature, historical locations or monasteries. Artists from Yugoslavia and international artists will be in residence for one to two weeks and communicate, debate, exchange, experience. I did visit many of them in Počitelj, Mileševo, Ečka, Bečej. I was running Deliblatski Pesak.” Milenko Prvački in conversation with the author, September 2021.

2 This questionnaire was conducted for the Tropical Lab Archive.

3 The selection of artists for this exhibition was done by faculty members from the following art institutions that partnered with Tropical Lab over the years: Institute Technology of Bandung, Columbia University, Zurich University of the Arts, University of Washington, California Institute of the Arts, Victorian College of the Arts–The University of Melbourne, Beijing Central Academy of Fine Arts, Pascasarjana Institut Seni Indonesia, Tokyo University of the Arts, Massey University, RMIT, University of Plymouth, University of Arts in Belgrade, Silpakorn University and LASALLE College of the Arts respectively.

4 Said 261, in Said, Edward, Culture and Imperialism, Vintage, 1993.

Essays

Social Distance

If you see someone without a smile, give them one of yours...

The tagline of countless motivational posters or staffroom mugs; words perhaps repeated before pulling on the Mickey Mouse hat for a day’s work at Disneyland. Despite the queasy overtones, the phrase sticks in my mind as the innocent, authentic exhortation of my father. My father—the inveterate hugger, scooper-up of lost souls, listener, counsellor, feeder, dragger of people on long walks.

My barometric measure of hospitality is calibrated to the weather my father created—the noisy, rambunctious melee into which solitary individuals would be ushered, another chair entering the ring of light, forcing the circle of seats ever further back from the dining table. My mother would eke out the meal and another blinking participant would be made warm in the glow of this generosity. Family legend also describes the way my sister once hissed to my mother that “Daddy has invited back the whole orchestra.” This type of largesse so lavishly unleashed is mostly perceived as a forcefield of good intent, a warming welcome, a show of acceptance of those beyond our ken, our kin—a flattening of difference. It is societally valorised to be seen as a ‘good host’ and rare to find a dissenting viewpoint. We have likely all at some time been the subjects of good hosts, felt the hand on our shoulder indicating acceptance, tasted the symbolic water or tea or wine, or broken the bread that signifies reception. We might well have been provided with a bed for the night, and offered company and safety in an unknown land.

The halo of nostalgia accompanying my childhood recollections diminishes with an investigative trawl through personal experiences of being a guest. Viewed both empathetically and retrospectively, the dazzled muteness of those on the receiving end of the ‘guesthood’ bestowed by my father may actually reveal annoyance or an acute discomfort of personal boundaries overstepped or individuality ignored. This threshold of hospitality, of bodies and places and perspectives, is a shifting and mutable territory, and as I revisit similar scenes, I recognise how nuanced and fickle these experiences are, how internally and subjectively such a public exchange is perceived, and how inadequate any universal notion of hospitality was.1

Perhaps we ourselves have inhabited that role of the cherished guest, whose gratitude is warmly anticipated by an attentive host, and we have felt that debt of appreciative gestures, correspondence, and gifts? The weight of this expectation colours and alters the guest’s behaviour as they strive to adhere to the cultural, performative and aesthetic expectations germane to ‘guesthood’. The labour to maintain the pliancy and bonhomie of this state can be overwhelming and exhausting on both sides, either to scurry to offer relaxation, or to visibly demonstrate the accepted levels of relaxation and to sensibly decode the degrees to which the offer to ‘make yourself at home’ really pertain.

Despite his own enthusiastic sense of hospitality, another one of my father’s maxims, “Fish, friends and family go off after three days,” is echoed by Lorenzo Fusi in the text which accompanied the 7th Liverpool Biennale.2 He describes the temporal problem implicit with many forms of hospitality: the implicit agreement that the guest will, for a short time, excitingly disrupt the equilibrium of the host’s domain, and then leave in a timely (three-day) fashion.3 This time limit would seem to me to be generous to both host and guest, providing a structure around which the rituals and spaces of hospitality can unfold, and the implicit message that the adrenaline required to inhabit this shared liminal space is finite.

So, what about that other guest? The guest who will not conform to unspoken rules, the one who will not leave, who seems not to notice your stifled yawns or the rumbling undercurrent of friction broiling in their wake. We can probably all remember guests such as these, whose innocent gestures, humour or even their apparel can seem designed, over time, specifically to madden and infuriate. The question “How long can you stay?” is charmingly uttered with a strained lilt at the end of the sentence and eyebrows smilingly raised in false accommodation. Overreaching hopes of hospitality and entitled expectancy create a chasm of misaligned intention, which the lingering guest ushers in and illustrates to an almost ecstatic degree of tension. The equal and opposing forces of guest and host each illuminate the other, and the equilibrium presupposed in the paradigmatic model of guest and host shifts dynamically whenever one party shifts to and fro along the spectrum— either failing to meet or exceeding the tacitly pre-agreed expectations existing in either party’s head. What it is, to be a guest or a host, and all the vagaries between the possible polarities of these positions will form the multiple perspectives of this piece.

I wanted to draw upon my own experience as an artist to reflect upon hospitality—both given and received—and to then use this example to unfold the metaphor of hospitality into a consideration of the political, social and environmental tropes of hosting and ‘guesthood’. I will be using the model of Tropical Lab as a lens through which to unpick artistic notions of ‘guesthood’, hospitality, and temporary community and to reflect upon the delicate and authentic welcome offered through the structure of the Tropical Lab international artistic residency, established by its host, Milenko Prvački. Tropical Lab is a residency programme which offers an atelier or hosting space within which artists from around the world can create, collaborate and share praxis, a literal laboratory for experimentation, an “annual international art camp for graduate art students” which I attended in 2015. The two-week period for which we artists were invited to make home at LASALLE College of the Arts overstepped the three-day temporal boundary in a manner exercised by countless artists embarking on international residencies. We brought, and were encouraged to bring with us, any tool literally or metaphorically required, our research and practice methodologies, a propensity for porosity, collaboration and participation, as well as a readiness to produce artistic outcomes emerging from this experimental period. The hidden ‘baggage’ that undoubtedly trailed us around baggage reclaim and the arrival lounge was a certain sense of entitlement and privilege—that we were invited.

Creating work during Tropical Lab with help from Marko Stankovic, University of

Belgrade, and Victoria Tan from LASALLE College of the Arts. Photo courtesy of

Kay Mei Ling Beadman, City University Hong Kong, 2015

Singapore struck me, during my time there, as a demonstrably cordial location, vivid with the industrialisation of hospitality, bestowing international largesse as a form of statecraft. From my arrival in Singapore’s luxurious Changi Airport, I was then smoothly whisked to the hostel which would house us for our stay. We were welcomed by student ambassadors who soothed our technological anxieties and led us to SIM card purveyors, then fed, watered, welcomed, entertained, sheltered. We were assured, through the internationally industrialised hospitality structures, of our guest status, and our roles as hosted participants was refined through the institutional introductory activities held at LASALLE. Beyond these formalised modes of exchange, however, we were enveloped in the warmth of Milenko Prvački’s, the ambassadors’, LASALLE’s and the wider city’s welcome. I was unaware at that time of the Singapore Kindness Movement, launched by the Singaporean Tourism Authority, which I first encountered in Irina Aristarkhova’s book Arrested Welcome.4 She describes similarly the overwhelming experience of arriving at the airport which, with its orchids, butterfly gardens and swimming pools, seems to be determinedly aiming for the very pinnacle of international air hospitality. She describes the city’s state-sponsorship of the tourism sector through the Economic Development Board and its goal of becoming the most welcoming international travel hub. She describes too how as a white woman she “benefitted from the racist and imperialist legacies of Singapore’s colonial history as part of the British Commonwealth, as well as from its postcolonial and authoritarian present, when tensions and inequalities around race were being managed by the government from the top down.”5

When I first arrived in Singapore, in July 2015, it was approaching the 50th anniversary of the city-state’s founding and there were abundant celebration plans afoot. My practice research is usually rooted in a geological, archaeological, historical enquiry and as such, during Tropical Lab I decided to build on previous research into the triangular trade routes of the Atlantic slave trade in the 17th Century. I was intrigued by the implicit role of the East India Company in this trade and their entanglement, through the import and export of cotton and other goods from India, via trading ports such as Singapore, to destinations such as Liverpool and Bristol, where they would then continue their journey to West Africa to be commodities traded in exchange for slaves. Plantations in the Caribbean were then worked by these slaves until the Abolitionist and Slave Uprising movements, whereupon indentured workers or coolies would then be brought in from India and China. Singapore was ‘settled’ by the piratical Sir Stamford Raffles on behalf of the East India Company, himself born on a boat off Jamaica, and it seemed to me that the ghostly traces of these trade routes clearly lingered, echoed in the business and busyness of Singapore’s international flight trajectories and shipping channels.

While in Singapore, I became acutely aware of the lack of visible history, but also the heritage traces which had been maintained, and preserved. Patrick Wright describes poignantly the view that “heritage is the backward glance taken from the edge of a vividly imagined abyss,”6 and it seemed to me that Singapore had inverted this western obsession with heritage and had, in the abyss, found its modus operandi. My fellow Tropical Lab alumnus, Singaporean Patrick Ong, spoke of how the number of storeys of each building had exponentially grown during his lifetime, each decade doubling, from four to eight to 16 and so on. The lack of nostalgia, my coming from a Britain that is both romanced by and myopically unaware of its own past, was refreshing, yet oddly haunting, as I hunted for any patina that might indicate past lives. At the same time, the throwback vison of the last-remaining kampong (traditional village) on the island Pulau Ubin, a “window into Singapore’s past,”7 and Raffles Hotel Singapore, “a heritage icon, whose storied elegance, compelling history and colourful guest list continues to draw travellers from around the world,”8 provided a fascia almost more sanitised than the version of Singapore that Resorts World™ Sentosa offers.

It appeared that in the same way that capable hosts provide the most sterile, edited and curated version of their homes for guests to appreciate, so too Singapore was tidying up and repackaging any messy or inconvenient histories into tourism packages.

A bewildering array of over 40 Passion tours are available through the official Visit Singapore website—focusing on food, action, socialising and ‘culture’. This catch-all term offers insights to the lives, among many, of those in Singapore’s Malay and Jewish communities, Chinatown, the Chinese cemetery, Little India, and more. If I were to undertake the Unity in Diversity tour, I would “get a better understanding of the racial mix in Singapore as you learn the different lifestyles and practices of these communities.”9 This well-meaning sentiment tries hard to offer a glimpse into the complexity of Singapore’s cultural and racial make-up, how these communities co-exist and feed into the global outlook of the nation state. The patchy reality I encountered in the run-up to the 50th anniversary celebrations was disorienting, vibrant and exciting, but troublingly asymmetric in the distribution of wealth. As a casual observer, the inequities woven into the East India Company’s historic ruling structure remained as visible stitches within the patchwork of the city.

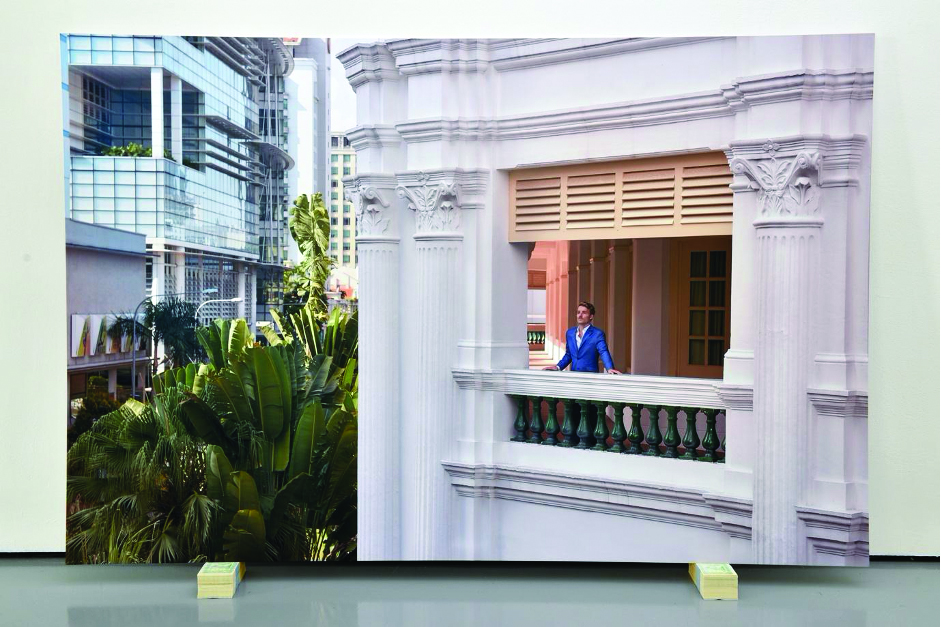

Feeling Raffled. 2015. By Andy Kassier, digital photograph on Dibond, 115 x 175 cm

Photo: LASALLE College of the Arts

As part of the Tropical Lab residency, I decided to make a sculptural ‘map’ of this multi-scalar, multi-temporal and multi-spatial web, perhaps a chaotic visualisation redolent of Benjamin Bratton’s theory of “the Stack,”10 a multidimensional computational model described by cultural theorist Jacob Lund as “the development of planetary-scale computation…which interconnects a number of different layers and facilitates interpenetration between digital and analogue times, and between computational, material and human times—bringing into being a kind of planetary instantaneity in which everyone and everything takes part.”11 Planetary scale computation would seem to be the material or immaterial equivalent to the East India Company’s trading goods, be they human, mineral or vegetable, and an equivalent too to the globalised transportation of goods as witnessed in Allan Sekula’s Fish Story, To be Continued which I was able to encounter at NTU CCA (Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art) in Singapore during the residency.12

Allan Sekula, The Forgotten Space (2010). Installation view in Allan

Sekula: Fish Story, To Be Continued, 3 July–27 September 2015.

Photo: LASALLE College of the Arts

The use of an industrial material redolent of a colonial past such as rubber, with its global history of imperial theft and colonisation of the landscape, seemed an apt vessel to carry these traces of cargo routes, inscribed with ongoing human loss. To source the rubber required—an inch-thick metre square slab, the tools and sacking material to print on—I repeatedly trawled the streets of Little India’s industrial vendors, a tall pale woman walking the humid streets in the midday sun, visibly adrift in this scene. Despite my solitary roaming and dishabituation in an urban environment, I always felt safe. This is afforded, in part, by Singapore’s famous civic ‘safeness’, of which it is justly proud, a companion to its legendary cleanliness and stringent legislation concerning the disposal of chewing gum. These urban ‘myths’ come to be true for many guests to the city-state, through their repeated tellings and experiences, but just as my children are exhorted to be on their best behaviour when guests arrive, this impression may extend only to certain groups or circumstances. During my long walks around the less pretty areas of Singapore, I knew that while the security, curiosity and hospitality I was experiencing was an incarnation of what I came to know as the Singapore Kindness Movement, I felt, too, a certain privileged entitlement to safety because of who I, as a white woman, was.

I remember as a callow youth spending a year teaching English (rather badly) on an island off the northern coast of the Central American country, Honduras. Ranked as a country with one of the highest murder rates per capita in the world, during that year, I vacillated between being bizarrely nonplussed by the ubiquity of firearms and being horrified by the associated fatalities and injuries among the community of which I had become a part. Throughout that year, despite the incredibly close shaves I encountered and survived, I felt myself insulated from real harm because of a (probably) misplaced confidence in my own importance. Surely these local ‘rules’ and dangers did not apply to me? Was this the safety promised by the offer of hospitality, or was it my privileged position as a white person, with the scrutiny of the charitable organisation I volunteered with and a powerful national embassy which scaffolded the precarity of my stay? The unevenness of this recollection brings into focus the key differences in expectation between being a guest and being a neighbour. Despite the year-long duration of my stay in Honduras, far in excess of three days, on reflection, I never truly troubled the definition of neighbour, despite superficially fulfilling Aristarkhova’s definition, that neighbours are demarcated by “their proximity in space (living near to one another) and time (being together in the same moment).”13 The temporary condition of my time there was always a given, there was always an end point in sight, akin to that moment of exhalation for a host when a guest leaves, the instance when the guest can resume his or her own routine and ritual. This mutability of time and space, between ‘guesthood’ and neighbourliness, resonates strongly with my experience of Honduras, and my impressions of Singapore. I strongly recall the lines of guestworkers queuing to return to their home countries as I departed Changi Airport at the end of my stay, this international limbo being something many of us have witnessed at other travel hubs around the world.

‘Guest’ is a term that can hide subtle violences: it can connote the idea of being detained, in the UK, ‘at her Majesty’s pleasure’ in a prison institute. The term that the gastarbeiter regime is a low cost means of increasing flexibility in cases of regional and/or sectoral bottlenecks in the employment system as well as a way of ‘exporting’ problems...”']gastarbeiter,14 which I came across as a German-learning teenager, also withholds the welcome that hospitality might be expected to convey. The term, meaning guest worker, emerged under a policy, which was developed in the 1950s following a series of treaties between Germany and other countries in which migrant workers to Germany were invited with the implicit expectation that when the required work was done, the guest workers would return to their homelands. The imaginative failure lay in Germany’s inability to anticipate that the temporary nature of the invitation was not made explicit. Germany’s Federal Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble said: “We made a mistake in the early 60s when we decided to look for workers, not qualified workers but cheap workers from abroad. Some people of Turkish origin had lived in Germany for decades and did not speak German.”15 The uneasy accommodation arrived at in this scenario of free(-ish) movement speaks of a failure of hospitality, or what Aristarkhova terms an ‘arrested welcome’. The state, in this case Germany, ‘generously’ offers hospitality, on their own terms, to their benefit, in the process making the assumption (probably drawn from their own privileged experience of being hosted) that it will naturally come to an end. The offer turns out to be hollower than expected—the terms perhaps unclear, or perhaps the opportunities available become too great to ignore and the stereotyping, the lumping together of inanimate groups of ‘others’ who ‘take advantage’, incrementally mutates into state-sponsored communal inhospitality.16 The grey area or threshold between hosts’ and guests’ expectations once again comes into question as does the scenario outlined by Lorenzo Fusi, as he states: “As for the household, so for the nation state.” He goes on to describe the conundrum for the civil state: “How can we articulate, politically, and demonstrate the notion of hospitality to those seeking shelter if hospitality is supposed to be temporary?”17