VOLUME

ISSUE 06

Citation: Déjà Vu

An odd intuitive feeling warms our heart and consciousness – déjà vu.

As migrating strangers, in search of a purpose, become common bedfellows of past and future they cite, recite, incite, and prophesize a paradox; A paradox which is a reverberating soundscape of change, of return. One where both cancel each other out in an audiotized schematic, whirling away only to remain a citation in memory. To attempt to cite, translate, decipher and re-member that moment of paradox fails as the speed of technologized everyday resists the mere attempt.

ISSUE 06

2017

Citation: Déjà Vu

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Essays

Exhibition

Conversation

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Citation: déjà vu

Essays

Need for Mondrian

‘public preposition’ – déjà vu? – collecting memories!

Art History and the Contemporary in Southeast Asia

Souvenirs from the Past that Never Was

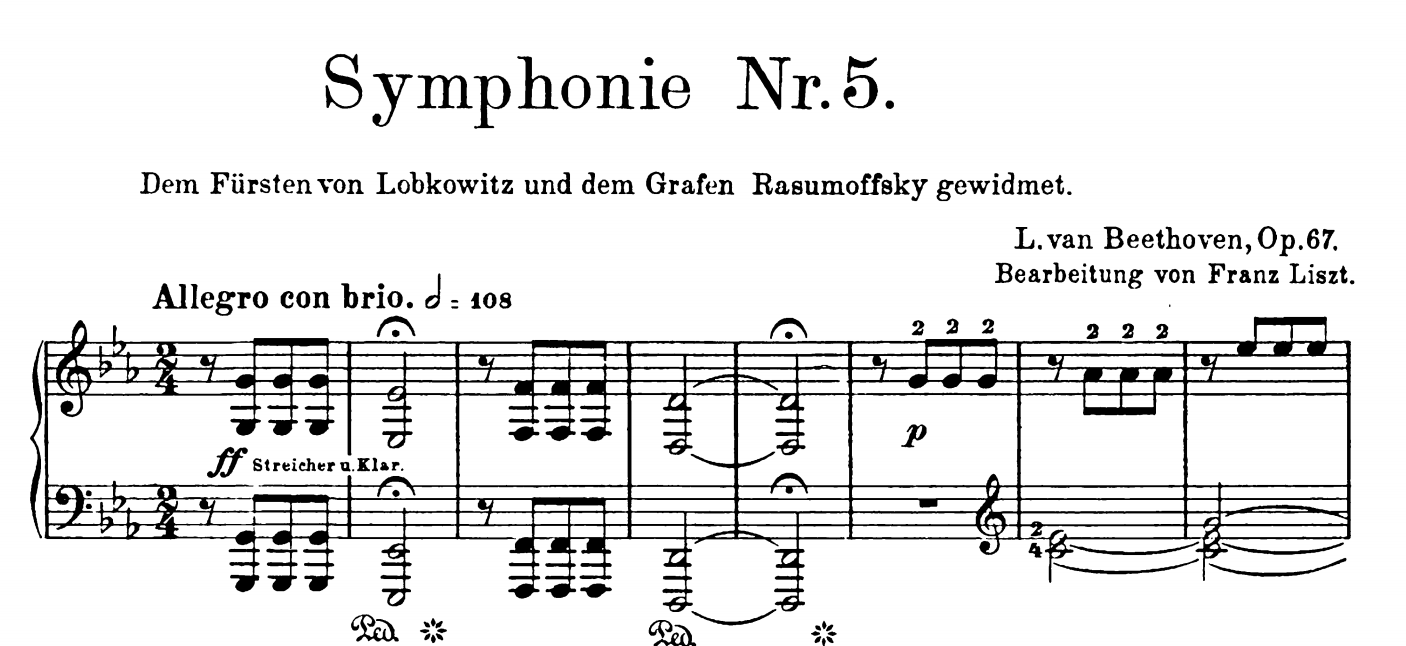

Everything Old is New Again: Musical Appropriation in the 19th and mid-20th centuries

Creative Futures

Aspirants

Exhibition

SOMETIMES I REPEAT MYSELF

Conversation

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy Editor

Jean Wong

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Manager

Layna Ajera

Contributors

Mitha Budhyarto

Joseph Curiale

Patrick D. Flores

Frank DeMeglio

Janis Jefferies

Mischa Kuball

Vanessa Joan Müller

Timothy O’Dwyer

Sava Stepanov

Jessica Berlanga Taylor

Susie Wong

June Yap

Introduction

Introduction: Citation: déjà vu

déjà vu.

As migrating strangers, in search of a purpose, become common bedfellows of past and future, they cite, recite, incite, and prophesise a paradox. A turbulent world remembered, as lines of humanity cross their geographical, existential and mediatised borders; as they open and close, appear and disappear: The strong flex, the small quiver.

We cite these moments. We recall we have been there before. A paradox which is a reverberating soundscape of change, of return. One where each cancels the other out in an audiotised schematic, whirling away only to remain a citation in memory. To attempt to cite, translate, decipher and re-member that moment of paradox fails as the speed of technologised everyday resists the mere attempt. One can instance the the speed. For example, the immediate availability of information today facilitated by technology demands a response of urgency providing little scope for referencing, citing and contextualising, which are being replaced by speculation, tip-offs and banter.

ISSUE 6 presents a rich and diverse set of artists, artist-scholars, curators, and researchers reflecting on and contextualising the issue of citation: déjà vu as they see it, and critically and refreshingly use it as a platform to reflect on the current conditions of the world.

We know the future because we have been there.

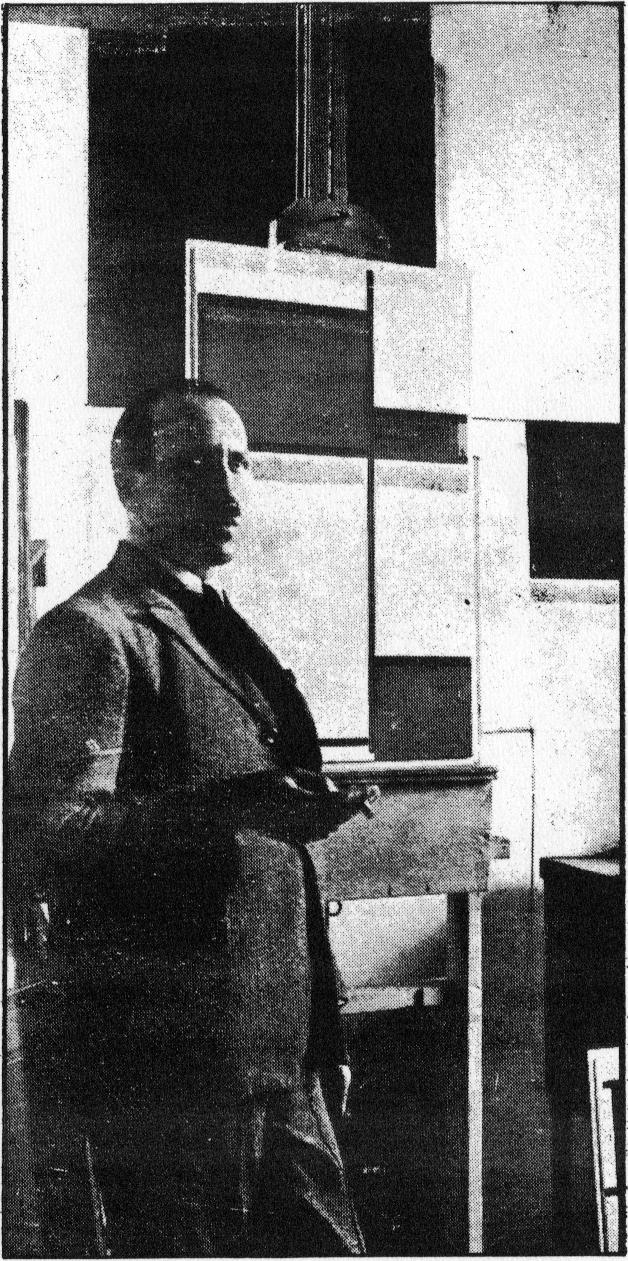

P. Mondrian in his studio in Paris. 1923.

Photo: Anonymous. From De Stijl, vol. VI, nr. 6/7 (1924): p. 86. Public Domain.

Essays

Need for Mondrian

By the end of the second decade of the 20th century, Piet Mondrian was already a formed landscape painter, slightly under the influence of Van Gogh, the Fauves and Pointillists. In 1911, at the Moderne Kunst Kring (Modern Art Circle) exhibition in Amsterdam, he became acquainted with the Cubist paintings of Picasso and Braque. For him, this was truly a watershed moment. Intrigued by new artistic tendencies, he moved to Paris that same year, joined the Cubists, socialised with them, and changed his painting style. In one of his reviews, Apollinaire soon noted Mondrian’s “very abstract Cubism.”1 Mondrian’s approach to Cubism is analytical – he radically dissolves a motif, insisting on the autonomous reality of image rather than the analysis of reality. Even at that time, Mondrian was systematic and gradually moved into the realm of abstraction. From the early 1912 to the summer of 1914, he got closer to the Purist understanding of line drawings – insisting on the inviolability of vertical and horizontal lines, and eliminating curved and even diagonal lines.

In 1914, because of his father’s illness, he was forced to leave Paris and return to the Netherlands. His father, a teacher and a religious fanatic, neglected the material aspect of existence, impoverishing the family because of his asceticism.2 Emerging from a rigid Protestant spirit, with an adopted Calvinist worldview, Mondrian’s Cubism of the time “was rational but not enough because it did not lead to the ultimate limit of reduction,” observed leading Italian art historian, Giulio Carlo Argan.3 Hence, Mondrian insisted on a drastic reduction: all was based on the rectangular positions of horizontal and vertical lines or regular square and rectangular planes, some of which he painted with primary red, blue and yellow. The solid, grid-like linear scheme became the conceptual basis of his paintings and his entire artistic philosophy. Mondrian’s contemporary, Herbert Read, identified the origin of this attitude. Forgoing all etiquette, he wrote: “Mondrian was not an intellectual in the conventional sense of the word and had no wide range of knowledge or experience. But he had mastered a vocabulary taken from a single source – the Dutch philosopher M.H.J. Schoenmaekers (Mathieu Hubertus Josephus Schoenmaekers).”4 Be as it may, Schoenmaekers appeared as an ideal interlocutor, because much of his philosophical discourse coincided with the Mondrian pictorial concept at the time. This refers, in particular, to the above-mentioned geometric linearism. In the book Principles of Plastic Mathematics (1916), Schoenmaekers wrote: “Nature is alive and unpredictable in its diversity, but basically it always works with absolute regularity, i.e. with plastic regularity,”5 whereas Mondrian, as pointed out by Herbert Read, “defines Neoplasticism as means by which the changeable nature can be reduced to the plastic expression of certain relations. Just like math, art becomes an intuitive means for presenting the basic characteristics of the cosmos.”6

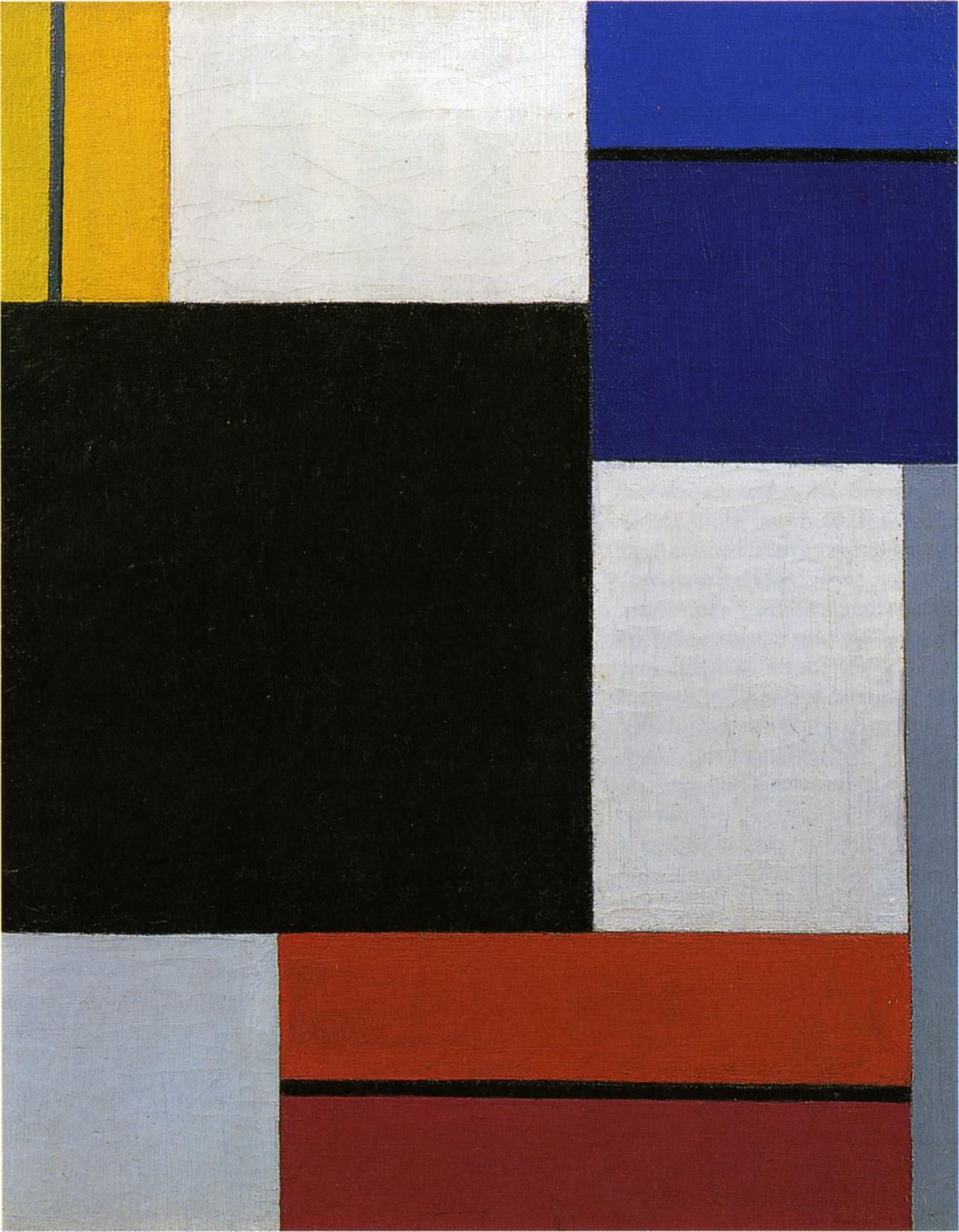

Theo van Doesburg, Composition XXI, 1923. Public domain.

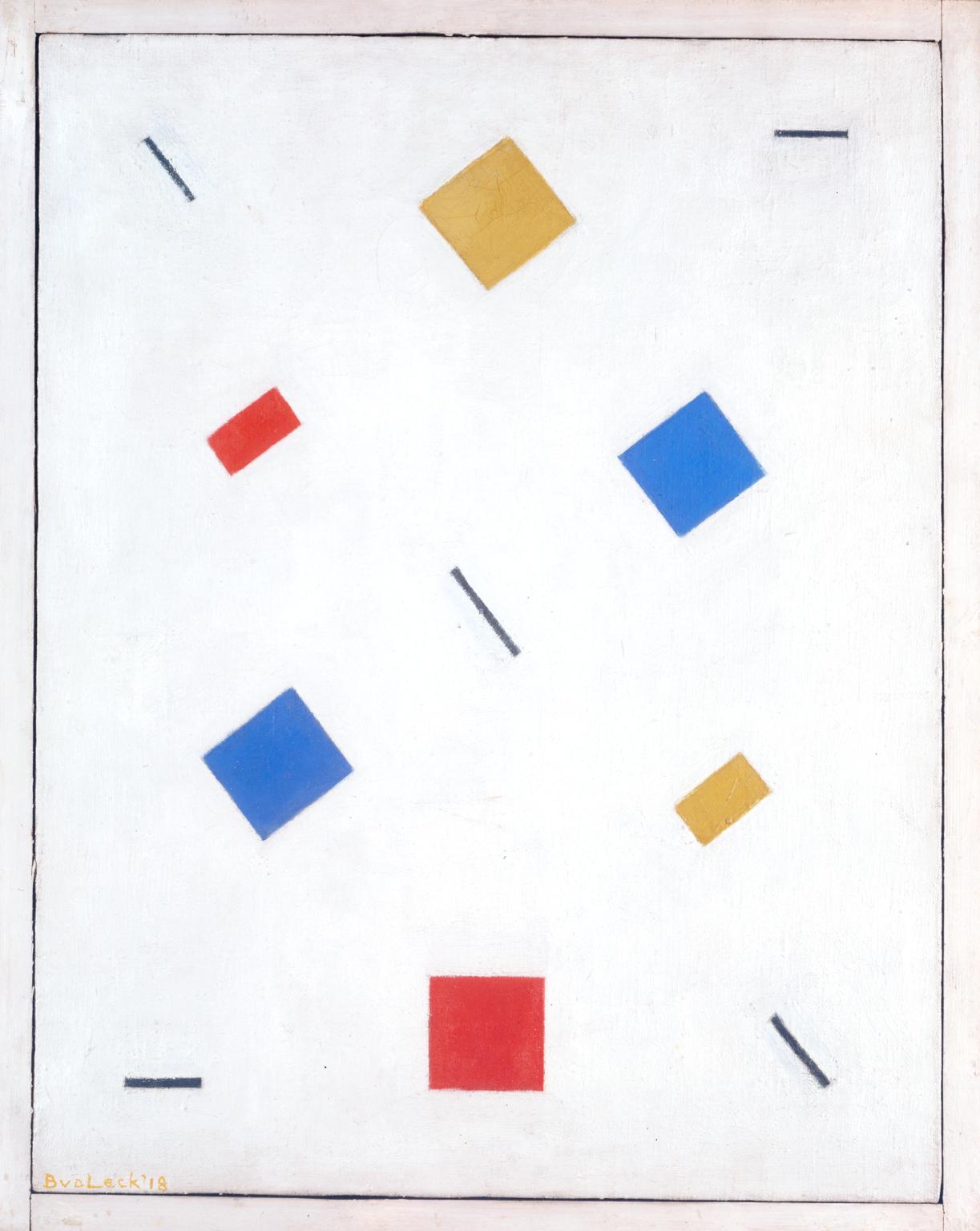

Mondrian met Schoenmaekers in Laren, a small Dutch town about 30 kilometers east of Amsterdam, where he lived during the Great War. During the First World War, Laren was considered an artistic colony and was even called the “little Paris.” During his stay in Laren, Mondrian did not paint. Rather, he devoted himself to philosophical discussions with Schoenmaekers and wrote articles on the theory of painting. There, he also met Theo van Doesburg and Bart van der Leck, Dutch artists with similar ideas about the image. They were both painters of abstraction based on a rectangular geometry, primary colours, and balanced relations within the image. Thanks to Doesburg’s initiative, the three of them soon became the pillars ofDe Stijl group.7

Although Doesburg was the initiator and leader of De Stijl, the most important member of the group since its foundation was Piet Mondrian. He saw art as a possibility for realising the ideals of universal order and harmony, and it is on these principles that the whole group operated. Mondrian discussed this utopian obsession in the article, Neoplasticism in Painting, published in installments in the first 12 issues of De Stijl journal. The principal aspiration of Mondrian and other members of the group was to impose the principles of geometric painting and architecture onto society. However, one should bear in mind that these ideas were conceived in a specific social context. Mondrian’s Neoplasticism has a genuine civic origin. As Karl Ruhrberg shrewdly observes, both Mondrian’s oeuvre and the whole De Stijl concept are reflections of the Dutch landscape stolen from the sea by man. They symbolise the supremacy of the human spirit which brings order to unbridled, unregulated nature. “This does not mean that painters secretly reproduce nature. On the contrary, it means that neoplasticistic painting is the fruit of the very same spirit that creates order. Peace, harmony and discipline are characteristics of this art and its utopian goal is the complete harmony of the world.”8

Bart van der Leck, Composition, 1918. Collection of Tate, DACS, 2017.

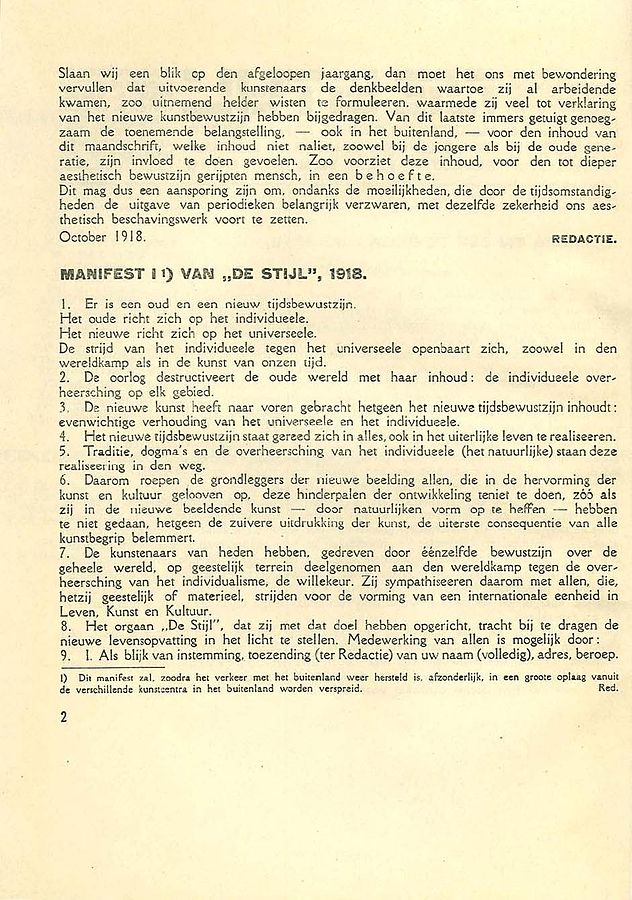

No matter how much this group of artists—gathered together in a small Dutch town of Laren in those dark war years—may have seemed “relocated” and isolated from the main trends of artistic modernity, today’s art history show that De Stijl made a major impact on the art and culture of the world. Argan notes that “De Stijl, in fact, is a key episode in understanding the history of contemporary art.”9 In the midst of rising political tensions, conflicts, the Great War, the Soviet revolution, the looming onset of Second World War, etcetera, the artistic idea of harmony was badly needed in the world. These were the circumstances and reasons that motivated not only Russian Constructivists and Malevich’s Suprematism, but also Mondrian’s geometric abstraction, De Stijl’s Neoplasticism, and the Bauhaus aesthetic. Amid the chaos of Europe during that time, artists were looking for different relationships, for harmony, for measure. The De Stijl’s Manifesto, written in 1918, states that the ongoing “war is destroying the old world with its contents and the new art brings a new awareness, a balance between universal and individual; and this new awareness is ready to be implemented in everything, even in outer life. Mondrian and the painters of Neoplasticism found this new awareness in their new organisation of image, especially in rationalist geometrism.” Argan aptly formulated Mondrian’s understanding of geometry in painting and art: “Ethica ordine geometrico demonstrata.”10

Manifest I of De Stijl, 1918. Public Domain.

Yet, art history tells us that Mondrian and his friends were not the only European painters of the time. The spirit of that time brought about changes. This will become especially evident once the closeness of Russian Constructivism, Malevich’s Suprematism, Mondrian’s rationalist abstraction, and De Stijl’s Neoplasticism is first observed and, perhaps, even more evident after their merger into the Bauhaus methodology. It was then, perhaps for the first time, that the ideal of the modernist awareness was realised. Filiberto Menna will later write about this in the book Project of Modern Art: “Aesthetic space therefore becomes a place for the movement of the individual in the direction of his full self-realisation: art activity, returned to the state typical of self-directed action, provides a model of behaviour and work upon which it is possible to establish a new relationship between subject and object, individual and collective. This is a romantic testament inherited by the artistic avant-garde movements of the 20th century and their aesthetic ideology: art is entitled to the autonomy of its own, not in order to be isolated but in order to offer its own model to other spheres of knowledge and practice.”11

Mondrian firmly believed in the same principles. For him, painting was increasingly becoming a social project for real life situations. After the end of the First World War, Mondrian returned to Paris and to his studio on Boulevard Raspail 278. It was there that he made his early cubist works, prior to 1914. His art, however, completely changed after the war. In line with new neoplasticist ideas, his work became plastically simpler, more socially effective, and more comprehensive. Mondrian completely rearranged his studio: he brought in minimalist furniture and painted the walls with black, red, blue, and yellow rectangles; he hung his characteristic geometric paintings on the walls; even his easel was precisely positioned as an object in a well-organised spatial composition. Mondrian’s studio space was arranged according to his pictorial scheme. The appearance of his artistic workshop was commented on by Carel Blotkamp: “His entire studio was arranged exactly as he imagined the world should look like - abstract and futuristic. His studio became a model of the environment he considered ideal: the walls were white, the whole space was very bright. The furniture was arranged in such a way that, when one looks at it, one gets the impression that it is a flat surface made up of geometric forms. His sofa, for example, looked like a black square from a distance. Even the easel, set against a wall, was an element of the interior, with its rectilinear form. Mondrian did not use it for painting; he painted at one of the tables. All this makes this whole thing exceptional, this absolute harmony of artistic expression and the space in which that expression becomes hypostatised.”12 Yet, no matter how harmonious the artist’s neoplasticist ideology, geometric paintings, and flawless studio environment may have seemed, Piet Mondrian’s life during his second Parisian period was very difficult. Neoplasticist works did not sell at all. In fact, it was only after 1921 that the classic Mondrian neoplasticist artworks were created. The first Mondrian painting was bought for a museum in Hanover in 1925. Between 1928 and 1932, he sold his paintings to several collectors from central Europe and America.

Mondrian’s art in the 1920s was adequate, necessary, and suggestive. Unfortunately, Adolf Hitler, after coming to power, saw such art as threat. In 1933, the Bauhaus closed and, in 1937, the Degenerate Art Exhibition was organised in Munich. The painting that Mondrian sold to the museum in Hanover was displayed. During this time, many artists left Europe. In 1938, Mondrian left Paris and went to London, where he stayed till the Battle of Britain in 1940. During the bombing of London, a bomb hit the house where he lived. After that, he moved to New York and lived in a studio on East 89th Street. Again, with a lot of enthusiasm, he arranged his studio in the neoplasticist manner. He put eight large compositions on the walls (collage wall paintings composed of monochrome sheets and little pieces of paper) and all the furniture was completely adapted to the surroundings. This enabled Mondrian to carry out his utopian ideas again and, as he himself said, it was the best place in which he lived. During his brief stay in New York, Piet Mondrian substantially influenced the development of post-war American modernism. His paintings—inspired by New York and jazz music—were much more dynamic than his earlier works. The dynamics of his intensely coloured squares between yellow lines depict the busy lifestyle of the metropolis, and introduced New York as a new centre for art in the aftermath of the Second World War.

After Mondrian’s death in 1944, his studio was opened to the public for six weeks. People were able to enter this castle of Neoplasticism and feel the revolutionary artistic idea which changed the former perception of the image and its meaning.13 In an article written on the occasion of Mondrian’s death, American theorist and renown promoter of American modernism, Clement Greenberg, wrote: “His pictures […] are no longer windows in the wall but islands radiating clarity, harmony and grandeur. […] Space outside them is transformed by their presence.”14

Greenberg saw the essence of Mondrian’s art. Geometry and simplicity in these images go beyond their aesthetic peculiarity, allowing this simple system of lines and squares, painted in primary colours, to become a plan and project of reality. Mondrian’s artistic concept is, therefore, frequently associated with architecture. Michel Seuphor began one of his essays by stating: “Mondrian is generally considered a father of modern architecture. This belief is one-sided and, indeed, false. Mondrian never made even the smallest architectural drawing. Although in his writings he sometimes talks about architecture, he essentially remains a painter, and believes that easel painting should introduce new times and forge a different society, in which architecture will indeed have an important place...”15

Gerrit Rietveld, one of the architects from the circle of De Stijl, was the first to apply the principles of Mondrian’s Neoplasticism in architecture and design. In 1917, he designed a chair that was inspired by Mondrian’s paintings. The design was very simple: it was composed of two well-balanced flat plates (the seat and backrest) that were supported by the frame of joints and slats. The plate surfaces were painted red and blue, with yellow slats at the intersections. All this was “embedded” in the supporting structure. In 1924, Rietveld designed and built the house of Schröder in Utrecht, marking a radical break from traditional architecture. The facade of this coherent minimalist building is pure and simple: clean white walls and panels, with visible structural elements (such as poles, railings, and window frames). Here too, Rietveld discretely uses Mondrian colours (red, blue, and yellow). The interior is flexibly designed. A series of sliding wall partitions make it possible to change the look and size of individual rooms. As noted by Argan, the Rietveld’s design and architecture, in this case, was based on the idea of pure construction.16 These are, perhaps, the first practical applications of Neoplasticism. In any case, today, a century later, they represent a model of European rationalism in architecture. The house of Schröder was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2000.

Even today, the link between Mondrian’s concept and architecture is relevant. Numerous buildings are built in accordance with more or less pronounced neoplasticist principles. Architecture still needs Mondrian, De Stijl and Neoplasticism. At the 2016 Biennale of Architecture in Venice, the Japanese artist, Hiroshi Sugimoto, presented his architectural installation, Glass Tea House Mondrian.17 The installation was set in a pavilion that had an open courtyard landscape and a closed glass cube. Sugimoto’s glass cube is the result of an experiment in which the artist searched for ideal relations and measurements, and strived to reach Mondrian’s aesthetic principle. He says: “I like to think that this tea house was designed by Mondrian.” Sugimoto’s exhibition concept relied on the subtlety of Mondrian’s reduced aesthetics, the subtlety which this Japanese architect synchronised with the subtlety of traditional Japanese tea ceremonies, thus achieving an effective contact of two aestheticisms, two cultures, and two different sensibilities.

Earlier this year, in 2017, monumental Mondrian paintings appeared on the facade of the Hague City Hall—a simple architectural building, completed in 1995, with a large interior space and stark white walls. This intervention on the facade of the building was done in celebration of the 100th anniversary of De Stijl and designed by one of the most respected American and international architects, Richard Meier. Meier’s architecture was a logical choice since his practice is deeply-rooted in the tradition of Modernism, De Stijl, the Bauhaus and Neoplasticism. The architecture stemming from the work of Mondrian and De Stijl is very functional; it has outgrown the formalism in which it was conceived; suggesting, even in early Rietveld examples, a specific architectural typology – where the neoplasticist architectural space is converted into a space on a human scale. Two artists from Rotterdam, Madje Vollaers and Pascal Zwart, came up with the idea of bringing Mondrian’s work into the urban setting of the Hague. They entitled their project The City as a Canvas.

The urban and architectural intervention in the Hague confirms the superiority of Mondrian’s painting. 2017 marks a century of the creation of Mondrian’s first “hard” geometric paintings in Paris (Composition in Black and White, Composition in Blue, Composition With Color Planes were all painted in 1917). Throughout this centennial period, Mondrian’s work has remained an authoritative aesthetic form in the world of painting, but also a relevant guideline to society in its everyday practice. The principles of his art are based on geometric harmony and structure. At first alone, then as a member of De Stijl, but also with the “recommendation” of the Bauhaus, Mondrian defined his work as a possible model for reality. The consequences of this attitude and behavior proved effective because its principles are applied in daily practice (architecture, interior design, applied art, fashion, music, etcetera). Significant contributions were also made by artists who accepted and developed the ideas of geometric painting and Neoplasticism after Mondrian’s death. Most prominent among them are his close associates from De Stijl who continued the group’s activities after 1944 – Dutch artists Bart van der Leck (1876-1958), Hungarian artist Vilmos Huszár (1884-1960), Belgian artist Georges Vantongerloo (1886-1965), and another Dutch artist Caesar Domela (1900-1992) who joined the group later, in 1925, as its youngest member. French artist Jean Gorin (1899-1981), another admirer of Mondrian, cultivated the concept of geometry and Neoplasticism since 1926, making a few “excursions” into the field of architecture.

Mondrian’s influence on American art during the last three years of his life in New York (from October 1940 to the beginning of 1944) is extremely important. In his essay, American-Type Painting, Greenberg expresses his appreciation of Mondrian’s work as “the most revolutionary move in painting” and considers Mondrian of vital importance to modernist processes in American post-war painting.18 The most dedicated Mondrianist in American art was certainly Harry Holtzman (1912-1987). Even as a young painter, he was inspired by Mondrian’s pictorial concept. In 1933, at the age of 20, he travelled to Paris to meet his idol. In 1940, shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, Holtzman was the one who organised Mondrian’s departure for New York, who found him an apartment and a studio, provided him with conditions for work, and became one of his closest associates. As a successor of Mondrian’s New York legacy, Holtzman deserves much credit for the promotion of Mondrian’s work in America.19 He was one of the artists who, in addition to adopting Mondrian’s concept, also saw to it that the concept was transformed into three-dimensional objects. For his part, Mondrian supported Holtzman, as illustrated by one of his letters where he enthusiastically praises the relationship between Holtzman’s canvases and space, noting that “in the present three-dimensional works of H.H. the picture […] moves from the wall into our surrounding space.”20 Holtzman was also supported by Burgoyne Diller (1906-1965) who, after a brief Cubist experience in the early 1930s, dedicated all his efforts to the neoplasticist painting of the Mondrian type, managing to introduce an impression of personality. Reputed art critic, Larson, observes that “Diller’s work serves as a vital link between American abstraction of the 1930s and Minimalism of the 1950s and 1960s, epitomised by […] Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly and Myron Stout.”21 Ilya Bolotowsky (1907-1981), an American painter of Russian origin, established himself as the admirer of De Stijl principles and Neoplasticism. He considered Mondrian his teacher. His entire opus was marked by a rationalist concept of the image. When she heard the news of his death in 1981, the New York Times critic, Grace Glueck, wrote: “Ilya Bolotowsky, 74, dies; a neoplasticist painter.”22 Bolotowsky’s retrospective exhibition, held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1974, confirmed him as the artist who, in 1936, was one of the founders of American abstraction. It is interesting to follow these (and other) American artists who developed their own geometric neoplasticist paintings. As for the functional distribution of the ideas of Neoplasticism and geometric abstraction, it turned out that, during the first half of the 20th century, the world really needed Mondrian’s model.

In the post-Mondrian period, after the instructive function of Neoplasticism lost importance because of the newly-established modernisms of the second half of the 20th century, the doctrine of Neoplasticism survived in a state of quiet and discreet functionality through various concepts of geometric abstraction. This preserved not only the autonomy of the medium, but also the aesthetic and ethical principles of the image established through the activities of Mondrian, De Stijl and the Bauhaus. The 1960s, marred by the Cold War, saw the emergence of the “New Tendencies” movement in Zagreb at a time when the starting position of the movement was, in a way, very similar to the initial situation of De Stijl and the Bauhaus. Actors of the “New Tendencies” were seeking the socialisation and democratisation of art because society needed a new art project and new support. One of the most prominent actors of the “New Tendencies” was the French artist François Morellet who, in the 1950s, in a letter to Victor Vasarely said that he had “discovered” Mondrian and his ability to rationalise the image.23 Morellet, just like Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg and other members of De Stijl, used geometry to overcome the problem of style and its identification with the artist’s sensibility and personality. This suited the spirit of the new tendencies in the inchoate computer and pre-technological age.

Artists often refer to Mondrian paintings in their works. In 1964, the American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein produced a series graphics glorifying Mondrian’s art model.

During the last decades of the 20th century, geopolitical changes in Eastern Europe caused numerous crises. Countries created after the war, amidst the disintegration of Yugoslavia, witnessed the re-emergence of Mondrian’s concept in contemporary art. Particularly in Serbia, the crisis has been unfolding for a long time: It started in the fatal 1990s. Burdened with destruction (political, economic, cultural, moral, etcetera) and the entropy of all values, the crisis turned into a long-term issue in 2000. Serbian artists confronted this social situation with rationalism, structure and harmony. This is also why they turned to Mondrian’s art. In 1992, at the beginning of the great crisis, three young Belgrade artists Aleksandar Dimitrijevic, Zoran Naskovski and Nikola Pilipović organised the exhibition “Project Mondrian, 1872-1992” to mark the 120th anniversary of the artist’s birth.24 They were ‘relying’ on Mondrian’s painting, Composition II, 1929, which has been displayed in the National Museum in Belgrade since 1931. At the exhibition, not one of them quoted Mondrian directly. Instead, by consistently implementing their own ideas of geometry—pure and extremely reduced understanding of the image and of painting—they tried to establish themselves through the principles of authentic aesthetic and ethical comment. As noted in the exhibition catalog by the Serbian art critic, Jesha Denegri: “The artists from this part of the world felt Mondrian to be close to them, and necessary, at the time which, together with everything else deadly and negative, brought into the field of art a surge of extreme localism and ideologically indoctrinated false patriotism. These artists tried to find a counter-response to this in the qualities and virtues of the spiritual, both sensitive and rational, even utopian (since “utopia”, Argan asserts, in the contemporary historical situation, still is the most concrete of all moral values), therefore, in all that is essential, as specifically embodied in Mondrian’s work.”25

The conclusion must be drawn that the paintings of Piet Mondrian are very much needed in the world and in art today. He is an artist who managed to turn painting into a project of social life. Argan notes: “He does not dream of a utopian society without contradictions, but a society which every day shows more ability to solve its own contradictions and does it in a reasonable and non-violent way […] Therefore, although his paintings look cold (or maybe because of it), Mondrian is, after Cézanne, arguably the greatest, brightest and most enlightened mind in the history of modern art.”25

Tomas Gerrit Rietveld, Red and Blue chair, 1917. Public Domain.

Mischa Kuball

public preposition / ghostTram

2013

Tram from Katowice and other Silesian cities operated after dark,

unpredictable route and travelling time, white foil, extra illuminants, light installation

Institution of Culture, Katowice / PL

Photo by Krzysztof Szewczyk, Katowice

© Archive Mischa Kuball, Düsseldorf / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Footnotes

1 Michel Seuphor, Mondrian – Peintures (Belgrade: Nolit, 1961) 10.

2 Darko Glavan. “Piet Mondrian, ‘He was a founder of Purist painting,’ ” Jutarnji list. 7 March 2015.

3 Giulio Carlo Argan, Achille Bonito Oliva, L’Arte Moderna, 1770-1979-2000: 105.

4 Herbert Read, A Concise History of Modern Painting from Cézanne to Picasso. (Yugoslavia, Belgrade, 1967) 198.

5 Read 200.

6 Read 200.

7 In addition to Mondrian, De Stijl’s leading members were Dutch painters, Theo van Doesburg and Bart van der Leck, Hungarian artist Vilmos Huszár, Belgian artist Georges Vantongerloo, architects Robert vanꞌt Hoff and Jan Wils, and Dutch author and poet Antony Kok. They were later joined by another architect, Gerrit Rietfeld. Mondrian wrote and signed the De Stijl Manifesto with these members in 1918.

8 Karl Ruhrberg, “Abstraction and Reality – Russian Revolutionaries and Dutch Iconoclasts (Suprematism, Constructivism, De Stijl),” in ed. Ruhrberg, Schneckenburger, Fricke, Honnef, Art of the 20th Century (Zagreb: Taschen, 2000) 168.

9 Argan 23.

10 transl. Ethics shown in geometric order.

11 Filiberto Menna, Modern project arts (Belgrade: Press express, 1992) 21.

12 Milica Dimitrijević (from the interview with Carel Blotkamp), “Mondrian would welcome guests in black suit,” in Politika, Belgrade: 7 January 2015.

13 Mondrian’s studio was inherited by his friend Harry Holtzman, a painter from New York. As official successor to Mondrian’s legacy, Holtzman established the Mondrian-Holtzman Trust and devoted himself to the preservation and promotion of Mondrian’s work by organising exhibitions, collecting documents, and publishing a book of Mondrian’s essays (1983).

14 Clement Greenberg in an “Obituary of Piet Mondrian, 4th March 1944, The Nation,” in Greenberg, Essays on post-war American art, 174.

15 Michel Seuphor, Mondrian – Peintures, ed. Fernand Hazan (Belgrade: Nolit, 1961) 7.

16 Argan 105

17 Hiroshi Sugimoto, Exhibition: Glass Tea House Mondrian, Biennale of Architecture, Le Stanze del Vetro, Venice, July 2015 - 30 July 2016.

18 Greenberg 30.

19 Immediately after Mondrian’s death in the spring of 1944, Holtzman opened Mondrian’s studio to the public for six months.

20 Piet Mondrian’s letters to the American artist Harry Holtzman Archive, Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie/Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD Archive) The Hague Netherland

21 Larson 15.

22 Grace Glueck, “Ilya Bolotowsky, 74, dies; a neoplasticist painter,” The New York Times: November 24, 1981.

23 François Morellet, “Lettre à Vasarely,” (1957), Mais comment taire mes commentaires (Paris: Ensba, 1999) 18.

24 Mondrian Project, 1872-1992. Organised by Aleksandar Dimitrijević, Zoran Naskovski and Nikola Pilipović, Gallery of the Cultural Centre, Pančevo, 1992.

25 Jesha Denegri, “Strategies of the Nineties: A Critic’s Standpoint,” Art at the End of the Century. Ed. Irina Subotić (Belgrade: Clio, 1998) 223.

25 Argan 108.

References

Argan, Giulio Carlo, and Achille Bonito Oliva. L’Arte Moderna 1770-1979-2000. Belgrade: Clio, 2005.

Blotkamp, Carel. Mondriaan: Destructie als kunst. Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 1993.

Denegri, Jesha. “Strategies of the Nineties: A Critic’s Standpoint.” Art at the End of the Century. Ed. Irina Subotić. Belgrade: Clio, 1998.

Dimitrijević, Milica. “Mondrian would welcome guests in black suit” (from the interview with Carel Blotkamp). Politika, Belgrade: 7 January 2015.

Everdell, William R. The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-Century Thought. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Glavan, Darko. “Piet Mondrian, ‘He was a founder of Purist painting,’ ” Jutarnji list, Zagreb: 7 March 2015.

Glueck, Grace, “Ilya Bolotowsky, 74, dies; a neoplasticist painter,” The New York Times: November 24, 1981.

Greenberg, Clement. “American type painting.” Essays on post-war American art. Novi Sad: Prometej, 1997.

Larson, Philip. Burgoyne Diller: Paintings, Sculptures, Drawings. exh. cat. Minneapolis: Alker Art Center, 1971.

Menna, Filiberto. Modern project arts. Belgrade: Press express, 1992.

Read, Herbert. A Concise History of Modern Painting from Cézanne to Picasso. Yugoslavia, Belgrade, 1967.

Ruhrberg, Karl. “Abstraction and Reality – Russian Revolutionaries and Dutch Iconoclasts (Suprematism, Constructivism, De Stijl).” Ed. Ruhrberg, Schneckenburger, Fricke, Honnef. Art of the 20th Century. Zagreb: Taschen, 2000.

Morellet, François. “Lettre à Vasarely” (1957). Mais comment taire mes commentaires. Paris: Ensba, 1999.

Piet Mondrian’s letters to the American artist Harry Holtzman Archive. Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie/Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD Archive). The Hague Netherlands.

Seuphor, Michel. Mondrian – Peintures. Ed. Fernand Hazan. Belgrade: Nolit, 1961.

Essays

‘public preposition’ – déjà vu? – collecting memories!

‘public preposition’ comprises a heterogeneous group of works, interventions, projects and performances that have been realised over the course of four decades or, for various reasons, are still awaiting their final realisation. These works appeal to a public, and question—by virtue of which site and under what conditions they occur—what “public” means. How is “public” constituted? What does participation signify without reducing the term to a vague offer to “join in,” or performatively integrating the viewer into an established constellation –touching topics that include aspects and observed notions of different cultural arenas and societies?

Memory and recalling historical or autobiographical narratives are key aspects of ‘public preposition.’ The context and content are based either on collective memories or individual components of recall. ‘Remembering’ becomes important in reflecting the current conditions of our societies.

Many of these interventions and projects have come into being by the invitation of art institutions or festivals and they exist for a limited time. Now, they exist via their photographic documentation. Other projects were consciously created to be ephemeral and had a limited visibility in their in-situ manifestation. Thus ‘public preposition’ refers to a fundamental contradiction of the term “public”: on the one hand, the public experience is understood as unrestricted; on the other, the “public” of an intervention is effectively limited to an event, its viewers and its participants.

For this reason, introducing ‘public preposition’ in a publication—which includes the presentation, discussion and documentation of projects—should be seen as an attempt to create a “public.” Furthermore, the publication integrates individual projects into a larger context. The key component, ‘remembering,’ is created predominantly through oral history or a collective narrative. By virtue of this, the publication will necessarily contribute to collective memory in the public sphere.

The idea that a text addresses a public is semantically embedded in the term “publication.” Furthermore, “making public” is conceptually implicit in publishing. Because the public is a social medium, the “making available” and communication of information play a fundamental role in its establishment. Without accessibility, information would remain reserved for a limited group of people. The notion of the public sphere as fundamental to democratic theory includes processes of general interest, communication directed at an unlimited audience, and the public accessibility of spaces and places.

To present, discuss and document ‘public preposition’ through its own publication is understood as contributing to producing a public, and integrating individual projects into a larger context. It works out the “family resemblance” of the different works—similar to concepts that cannot be adequately captured within a taxonomic classification (because of ambiguous boundaries) but which still form a unified group.

‘public preposition’ is an open concept that develops and reacts to specific situations—spatial as well as social, historical and political. Depending on the situation, the approach changes. Light as an accentuating medium that creates visibility yet that is itself immaterial, often yields entry to the development of new social and communicative spaces of experience. When conceptual artist, Kuball, utilises light, he is not just illuminating and focusing on what has, until now, been hidden. Rather, he is drawing attention to what is present, and fathoming its undiscovered or forgotten potential. In the scope of ‘public preposition’ light stands for reflection in two senses: as a mirror of that which exists and an analysis of it.

For ghostTram in Katowice in 2013, Kuball converted a local transportation tool into a six-day performative intervention. Backgrounded by an unstable German-Polish history, the Upper Silesian region around Katowice is an economically-flourishing Polish metropolis today. Years of shifting borders, occupations, expulsions, settlements and evacuations had shaped its identity. The tramnetwork of Katowice and its surrounding cities, dating back to 1894, now belongs to one of the largest transit systems in the world. In cooperation with the Katowice Cultural Institute City of Gardens, a historic tram from the 1980s was illuminated and sent out on nighttime journeys without passengers, scheduled service stops, or a destination. In the darkness of the night, the “ghost train” seemed to be going nowhere. It was like a glistening white cube, set free from its original function, history and materiality. It was without background and without destination. It was without identity. People from Katowice wrote letters to the Mayor’s office reporting that their grandparents had sat in that tram; the Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz, is nearby, and the authors of those letters connected the public intervention with their historical trauma.

Solidarity Grid in Christchurch, New Zealand was not only one of the most extensive and permanent works from ‘public preposition’ but also the work with the most complex genesis. Against the backdrop of two severe earthquakes in New Zealand, a seminal project was developed with the involvement of the local community. Blair French, the curator of SCAPE Christchurch Biennial, who had invited Kuball to create a work for the Biennale in 2013, described the various stations Solidarity Grid had to undergo, how it emerged from the on-site analysis of the situation, and his collaboration with various players. In this context, the term “site-specific” also receives another far-reaching significance. Globalisation identifies historical particularities of urban structures beyond those currently visible. Kuball pursued to question the relationship between public and private, which have become imprecise terms, and the zone between them. To say that his work consciously plays with concepts like the Agora and public space, and tests modalities for their production or reactivation, suggests that it would be hasty to dismiss these in their historicisation. The question of the status of the public, which dominates the entire work, and the relationship between the audience and the work, will also be discussed.

‘public preposition’ was published in 2015 by DISTANZ Verlag. Edited and with text by Vanessa Joan Müller

Mischa Kuball

public preposition / ghostTram

2013

Tram from Katowice and other Silesian cities operated after dark,

unpredictable route and travelling time, white foil, extra illuminants, light installation

Institution of Culture, Katowice / PL

Photo by Krzysztof Szewczyk, Katowice

© Archive Mischa Kuball, Düsseldorf / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Mischa Kuball

public preposition / ghostTram

2013

Tram from Katowice and other Silesian cities operated after dark,

unpredictable route and travelling time, white foil, extra illuminants, light installation

Institution of Culture, Katowice / PL

Photo: Krzysztof Szewczyk, Katowice.

© Archive Mischa Kuball, Düsseldorf / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Mischa Kuball

public preposition / ghostTram

2013

Tram from Katowice and other Silesian cities operated after dark,

unpredictable route and travelling time, white foil, extra illuminants, light installation

Institution of Culture, Katowice / PL

Photo by Krzysztof Szewczyk, Katowice

© Archive Mischa Kuball, Düsseldorf / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Mischa Kuball

public preposition / MetaLicht

2012

Light installation, 760 metres LED lights from the company Zumtobel,

DMX-control, 7600 Watt (10 Watt / metre), three small wind turbines type AeroviS T7 and vertical rotors

Bergische Universität, Wuppertal / DE

Photo by Eberhard Quaas, Wuppertal

© Archive Mischa Kuball, Düsseldorf / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Mischa Kuball

public preposition / MetaLicht

2012

Light installation, 760 metres LED lights from the company Zumtobel,

DMX-control, 7600 Watt (10 Watt / metre), three small wind turbines type AeroviS T7 and vertical rotors

Bergische Universität, Wuppertal / DE

Photo by Achim Kukulies, Düsseldorf

© Archive Mischa Kuball, Düsseldorf / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Essays

Art History and the Contemporary in Southeast Asia

This essay builds its argument around the relationship between contemporary art and art history. There is a tension that underlies this relationship mainly because the modernity of art is increasingly unable to regulate the interests of the contemporary, which in turn could not seem to elude the modern as its foundational discourse.

That said, the modern art museum persists to encompass the contemporary in the belief that the modern is always emergent and self-renewing, capable of marking the progressive in the contemporary. This modernity has shaped the history of art history as a discipline forged in the 19th century and linked to the formation of the museum, the nation-state, and a particular phase of capitalism.1 The discipline of art history has experienced a crisis of its methodology and scope, and has tried to expand itself beyond its zone of expectations. This expansion, however, has failed to radically reorganise its methodology. It tries very hard and, sometimes, belabours in vain to represent other art worlds through the very procedures of explanation that have refused them. In other words, it is imperative for art history to recast itself or to cast itself elsewhere: in the afterlife of the modern that conceived it. In this endeavour of recasting, we ask: How does an emergent modality of critical inquiry conceptualise this elsewhere and in this afterlife?

In Southeast Asia, the writing of the history of art has not been strictly guided by the discipline of art history. In terms of scholarship, the history of art proceeds from the concept of comparative modernity, with modernity as the main mode of explaining art and its vehicle for comparison across diverse art worlds. It is also through this concept of modernity that a range of differences plays out: non-modernity, anti-modernity, post-modernity, tradition, contemporary, and so on. The other mode is the ethnographic that tells stories of artists and the ecologies in which they work. It serves as an alternative to a strict art history, in light of the absence of a deep archive of art. The third mode is the contemporary in which the history of art is, at a certain level, narrated and reflected upon through the production of art in the present; a present that reflexively implicates the conditions under which art has been historicised.

This excursus looks at four instances in Southeast Asian art that foregrounds the contemporary as a mode of access to art history. These instances offer up four themes about the relationship between art history and the contemporary as well as speak to the concerns of this problematic dynamic, namely: the supposedly paradoxical liaison between past and future. The rubric of art history and the contemporary at a significant level indices this constant “déjà vu”— a recurrent condition that actually exemplifies the comparative, in which the progressive is arrested by the antecedent; or the vision of a possibility is bedevilled by an anxiety of history. What might be productive to contemplate is how theory puts in place the terms “end” and “post” in the exceptional markers of the self-consciousness: the modern, the colonial, and the historical.

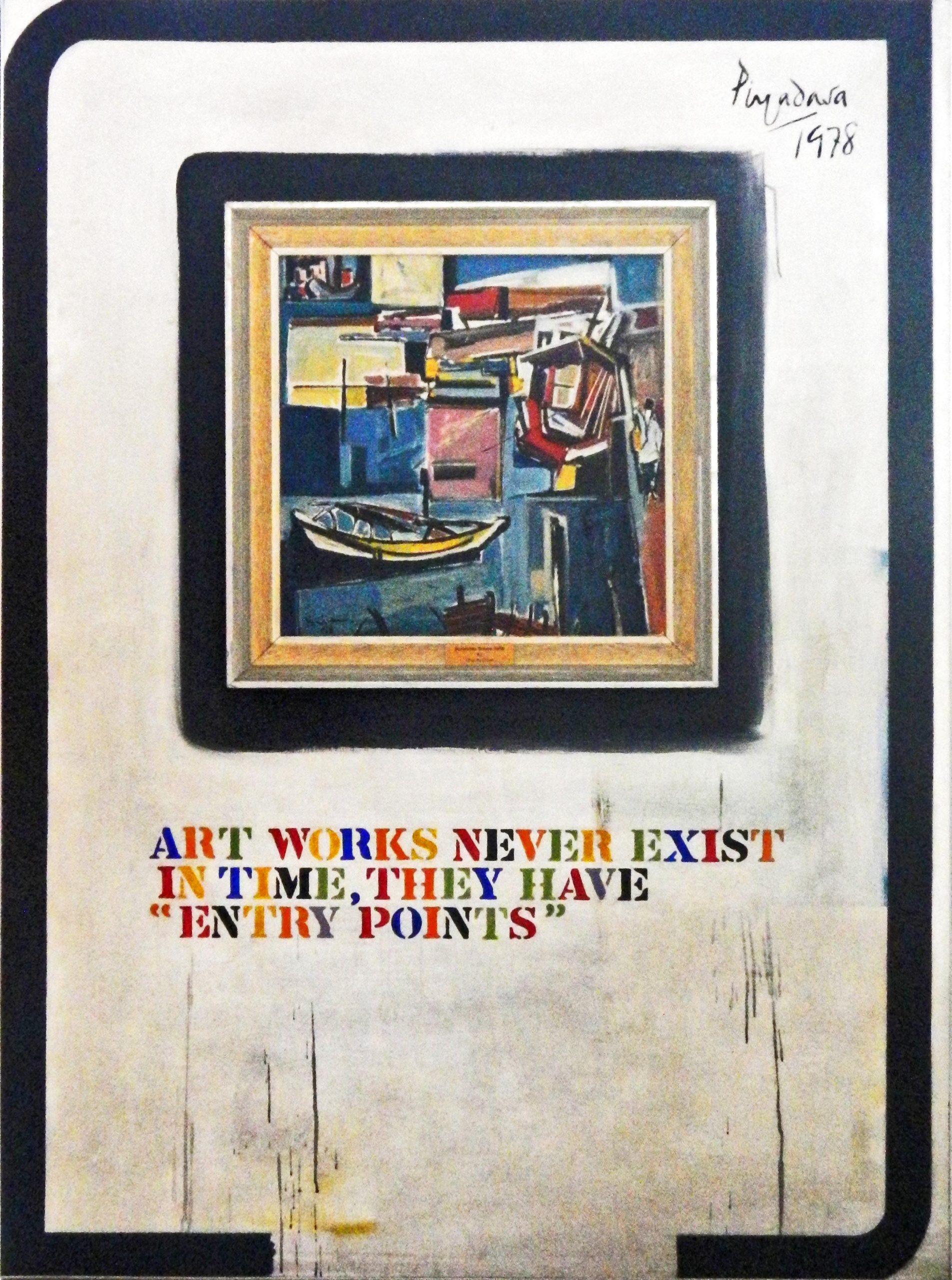

Redza Piyadasa,

Entry Points, 1978.

Mixed media.152 x 112 cm.

Collection of National Art Gallery Malaysia.

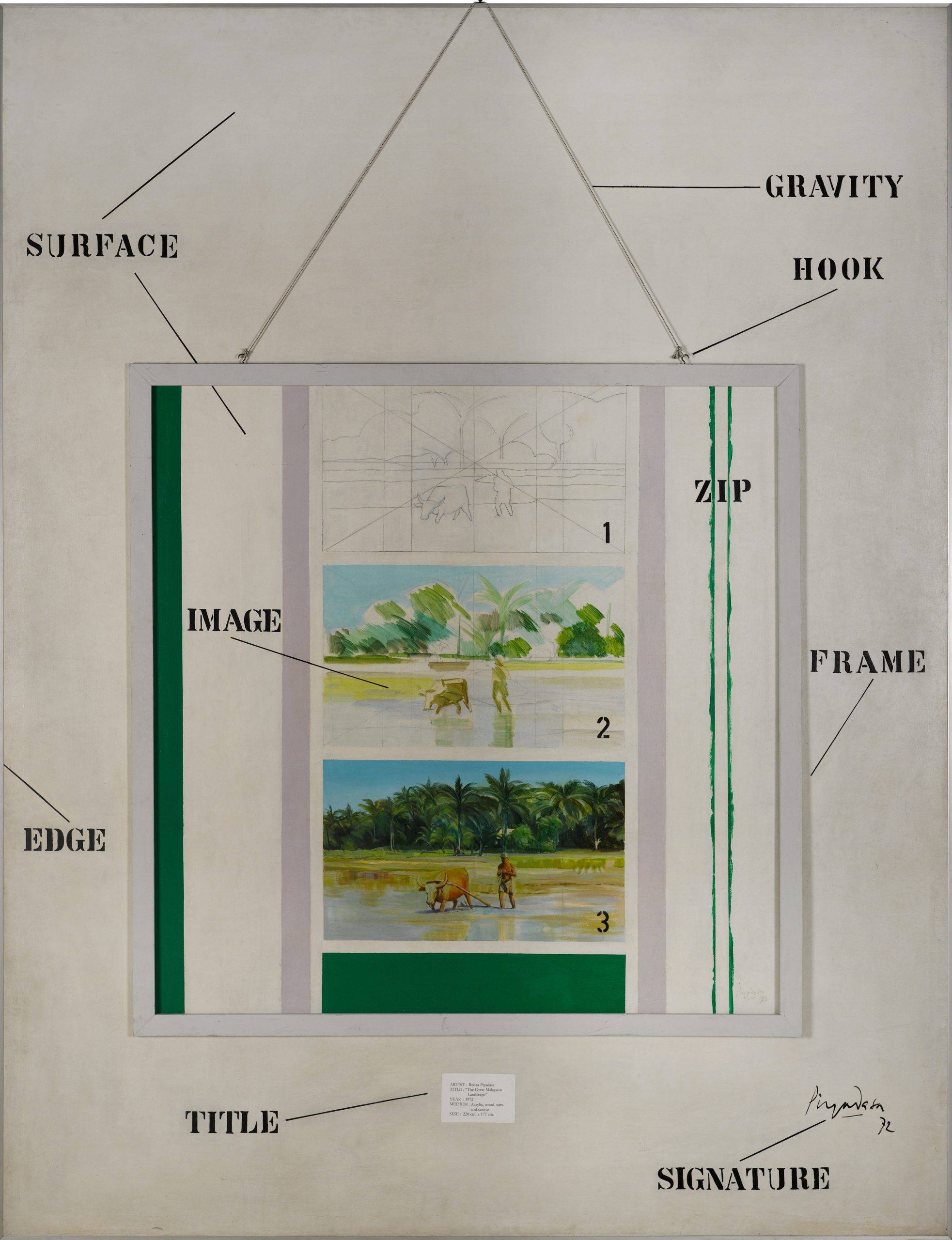

Redza Piyadasa,

The Great Malaysian Landscape, 1972.

Acrylic and mixed media. 152.5 x 106 cm.

Collection of National Art Gallery Malaysia.

Thesis 1: The contemporary locates trajectories.

“Art works never exist in time, they have ‘entry points.’” This quote is taken from Redza Piyadasa’s mixed-media work titled Entry Points (1978). It assimilates a 1958 painting by Chia Yu Chian titled River Scene into an otherwise bare canvas, stained only by trickles of paint, a broken border, and the stenciled sentence that disfigures the scene of the painting. Piyadasa’s comment tracks the modernity of art in terms of trajectories, not origins; transpositions, not lineage nor linearity. The idea that the work of art is approached through “entry points,” as opposed to having a fixed temporal existence, significantly skews the history of modernity. In particular, its self-fulfilling prophecy of progress may actually be a chronicle of a stasis foretold. Interestingly, the presence of the artist and the painting references the Nanyang School/Style.2 Chia Yu Chian was studying in Singapore at the time the work was painted, and this may have been Piyadasa’s way of calling out an entry point into a modernity in Southeast Asia that is being consolidated as a region—through a school of artistic and cultural thought—under the aegis of the Nanyang or the South Seas.

Phaptawan Suwannakudt,

Nariphon I, 1996.

Detail (image with the tree).

Acrylic and gold leaf on silk. 165 x 80 cm.

Courtesy of the Artist.

One such trajectory is the critique of art itself within the practice of artmaking, rendering the “critical” formative of the “artistic” at the fringes of autonomy. As a conceptual artist in the minimalist, kinetic, and constructivist vein, who questioned the basis of modern art and later the discourse of nation in Malaysia, Piyadasa first tried to reconceive the form of art, in his own words, as a “meta-language” within the purview of a Western avant garde. According to him: “My arrival at conceptual art engagements by the mid-1970s was prompted by the need to transcend the limitations of a painting/sculpture dichotomy as defined by Western art historicism. The attempts to break down separations between painting and sculpture were central preoccupations of the 1960s, very much a part of my generation’s concerns.”3 In this specific instance, contemporary art opens up a new way of imagining how art takes place, and is not merely mapped out across or grafted onto a grid called Art History. Here, the contemporary creates the conditions of the historical in relation to the passage of art.

Phaptawan Suwannakudt,

Nariphon III a, 1996.

Detail (image with three girls on the left).

Acrylic and gold leaf on silk. 90 x 90 cm.

Courtesy of the Artist.

According to Piyadasa’s account of the history of modern Malaysian art, in his earlier work The Great Malaysian Landscape (1972), “a conscious attempt has been made to focus on what has been termed the ‘eye/mind’ conflict in modern painting by the use of visual and verbal components.” This reflexivity lies in “a parody of the painting-within-a-painting situation…in which the stenciled words draw attention to…rhetoric governing…modern painting…. (and) questions about the nature of painting.”4 Here, the contemporary artist is also an art historian, and so conflating the tasks of production and historicisation that are performed, impressively, by the same person.

Thesis 2: The contemporary reinvests tradition.

There is the impression that the contemporary is the opposite of tradition, and that tradition needs to be transcended so that change can happen. Contemporary art has complicated this notion. The artist Phaptawan Suwannakudt from Thailand exemplifies the condition in which the contemporary cannot be rendered possible without the skill honed in the context of tradition. Tradition may mean the supposed knowledge generated before the time of the modern. What the contemporary tries to do is to cross the unnecessary gap between modernity and tradition. Phaptawan is the daughter of the esteemed Thai mural painter Paiboon Suwannakudt, and learned the techniques of mural painting under his guidance. When Paiboon died in 1982, Phaptawan, who spent her childhood in a Buddhist temple, assumed the role of her father and completed commissions for temples and hotels in Thailand for 15 years. Phaptawan’s practice has been a conversation between this history of skill and talent, on the one hand, and the demands of the present on subjectivity and agency, on the other. At this point, the question of gender and locality intersects with the conditions of migration. When Phaptawan moved to Australia in 1996, she described herself as a “Thai mural painter”5 but began painting on easels instead of the wall. Her work over the years, however, has revealed an array of expressions that enhance while simultaneously lightening the burden of this characterisation of the self. In many of her pieces, she is able to reflect on displacement and resettlement, and references modernism and customary forms of image making. For instance, her first paintings in Australia titled the Nariphon series (1996), feature gum tree figures in the scene. She relates that she “unconsciously painted a gum tree bearing its girl-shaped fruits to tell a story of an incident in a province of Thailand when a 12-year old girl was sold by her parents.” In a later work titled Journey of an Elephant (2007), she paints the trees she encountered in Sydney, names them in a language she knew intimately, and layers them with the text of a short story her father had written. This layering of worlds, texts and visions is also evident in Three Worlds (2009).

The art critic Flaudette Datuin points out that it was Phaptawan’s father “who taught her to discipline her hand through a mindfulness honed by meditation and guided by the Buddhist conviction that the ‘mind is the body and the physical is a vessel,’ from which we depart when we die. Form in Buddhist painting, she believes, is likewise a ‘vessel, in which the mind of the painter dwells. The mind dwells on the work during the process of painting, and when it departs, I leave the vessel behind. My work moves on from one vessel to another.’”6 Datuin further states: “when she was 14, for example, she asked her father why the line and form of water in his mural paintings did not look like the water she sees in a nearby river. Her father sent her back to look at the river again but this time with her eyes shut. ‘He then told me to empty the visual from eyes of flesh and see again.’ When she begged her father to teach her how to paint, he asked her to draw leaf after leaf, thousands of leaves, page after page. When she started painting murals herself, she did so with a watchful mind that observes the moment and movement of the brush/pencil entering and departing the surface. And every time she ‘arrives at the departure,’ she ‘catches the moment of the unattached mind. The watching of the mind will carry you through several enterings and departures [over] and over again.’”7

Thesis 3: The contemporary redistributes the modern.

An important element in the climate of contemporary art is the market. It is an issue that is, more often than not, repressed in the discussion of the aesthetic or isolated as a sociological matter, as if the production of art were not either a critique or affirmation of the capital that has produced it in the first place. The couple, Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, confronts the market by way of art history. The artists converse with the art of Antonio Calma, someone who bears the stigma of being labelled a Mabini artist, a term assigned to painters who are deemed commercial. The term comes from the street on which they ply their trade, the same vicinity in which some conservative painters in 1955 relocated their works, after walking out of a competition in the annual salon that, according to them, favoured modernism. Mabini, therefore, serves as a sign of decline and persistence, an enduring salon des refusés that is contemporaneous with modernity. Calma is the Aquilizans’ contemporary in the art world; but he only makes sense in Mabini while the Aquilizans are supposedly global artists in biennales and art fairs.

Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan,

FRAMED: Mabini Art Project at Art Fair Philippines, 2016.

Installation view. Courtesy of Alfredo Jojo Gloria and Art Fair Philippines.

In the hands of the Aquilizan couple, the works of Calma are subjected to different configurations: stacked into a column or a pile of canvasses, cut up and reframed, recast as minimal sculpture or readymade conceptual art that is totemic or muralist in aspiration, but still retaining the signature of a fragmented, miniaturised Calma. He has become some kind of a co-author, or cooperator, of contemporary art that has mutated into abstract, impressionist, informel, brut, nouveau realist, and so on. What happens to Calma is difficult to track, which is why this provocation is indispensable—it is at once so disturbing and so beautiful, with Mabini art finally becoming contemporary and museum-worthy, though slaughtered, so to speak. It is only through this slaughter that it achieves an aesthetic quality meaningful in the legitimate art world, but it is a slaughter that nevertheless denies it its own tradition on the street where it lives. This process of transformation of Mabini painting from commercial painting into an installation began in 2007. In a way, contemporary art reverts to a history of kitsch to achieve its valence of modernity.

In Art Fair Philippines in 2015, a reprise of this project was staged. A documentary was exhibited alongside a motley of pictures. In this theatre, Antonio Calma sat comfortably for the camera, posed against the fabled and majestic Mount Arayat, the mountain that presides over his place. Calma was actually ensconced. After all, this is his social world, his art world. He is a painter of landscapes, including the one that frames him. It is one that he sells quite copiously in his trade. He is what they would have called, back in the day, oftentimes with condescension if not outright derision, a Mabini artist; in our own time, he persists to stand his ground with his own gallery in Pampanga and Tarlac—a nest feathered by an atelier of artists and a cohort of loyal clients.

For the Aquilizans, the discourse around Mabini is a viable site from which to think about the circulation of art and the creation of its value: from the origins of the market during the reign of Fernando Amorsolo in the first half of the 20th century to present day scenarios in which primary and secondary markets briskly interact (sometimes vertiginously brisk). Mabini references a lot of logics vital to the commerce of art. It also implicates the afterlife of 19th century academic realism as a foundation of tourist and souvenir art in the American period when the Philippine exotic would be accessed partly through paintings of tropical charm and colonial curiosity. It relocates Amorsolo, the most well known Philippine painter in the first half of the 20th century, from a revered master of romantic realism, who is seemingly beyond the machinations of money, to a purveyor of taste and things in a wider economy of both kitsch and collectible. Finally, it complicates the notion of the contemporary itself. How do artists like the Aquilizans appropriate the lively practice and ecology of Calma in the context of contemporary art? Can Calma survive the translation or is it only the Aquilizans who gain from this contentious gesture? Both Calma and the Aquilizans have been recognised because of this project: exhibition presence for the latter and business prospects for the former. Can there be reciprocal mimicry here?

These questions are not masked in the art fair. Rather, they are laid bare, better for the public of the art fair to keenly revisit questions of value and the social life of commodities. In previous collaborations with Calma, the Aquilizans had radically intervened to make Calma’s oeuvre look like much more than it is in Mabini and its satellite retail outlets. In this fair, the Aquilizans decided to pursue another trajectory. They practically transplanted the gallery of Calma from its home grounds to the premises of the fair, and set it up as a gallery like any other display at the event. Iterations of the corpus of Calma, as at the Fair, has been significantly mediated by the Aquilizans and by this, the discipline of art history encroaches to historicise it. This cohabitation is meant to confuse, to productively confuse, so that the idea of the market and its political economy are viewed from a broader vantage, and that the modernism of art does not elude the critique usually reserved for commercial interests enslaved by lucre. An argument can be made that it is commerce all over, just like the salon hang of the works in both the galleries of Calma and the Aquilizans. And if it is so, is there nothing outside it? Does inserting Calma into the art fair circuit merely indulge the market, or does it finally disabuse it?

Thesis 4: The contemporary masters and mimics the Western gesture.

The work of the artist Mahendra Yasa, who works in Bali, exemplifies this final thesis. In contemplating contemporary form, he is seemingly bedevilled by a double vision: the vision of Balinese painting that has defined the idyllic conception of Bali and the vision of Western art, specifically American modern art, in an effort to overcome the dichotomy sustaining those binary visions. What he does is to transpose the techniques of Balinese painting to simulate the effect of so-called Western modernism. The effect is mimicry of the Western and mastery of the Balinese, an overinvestment in the production of surface almost on the level of obsession and devotion related to craft and ornament. It also references the viable commerce of painting in Bali that simulates Western style and exploits the local expression.

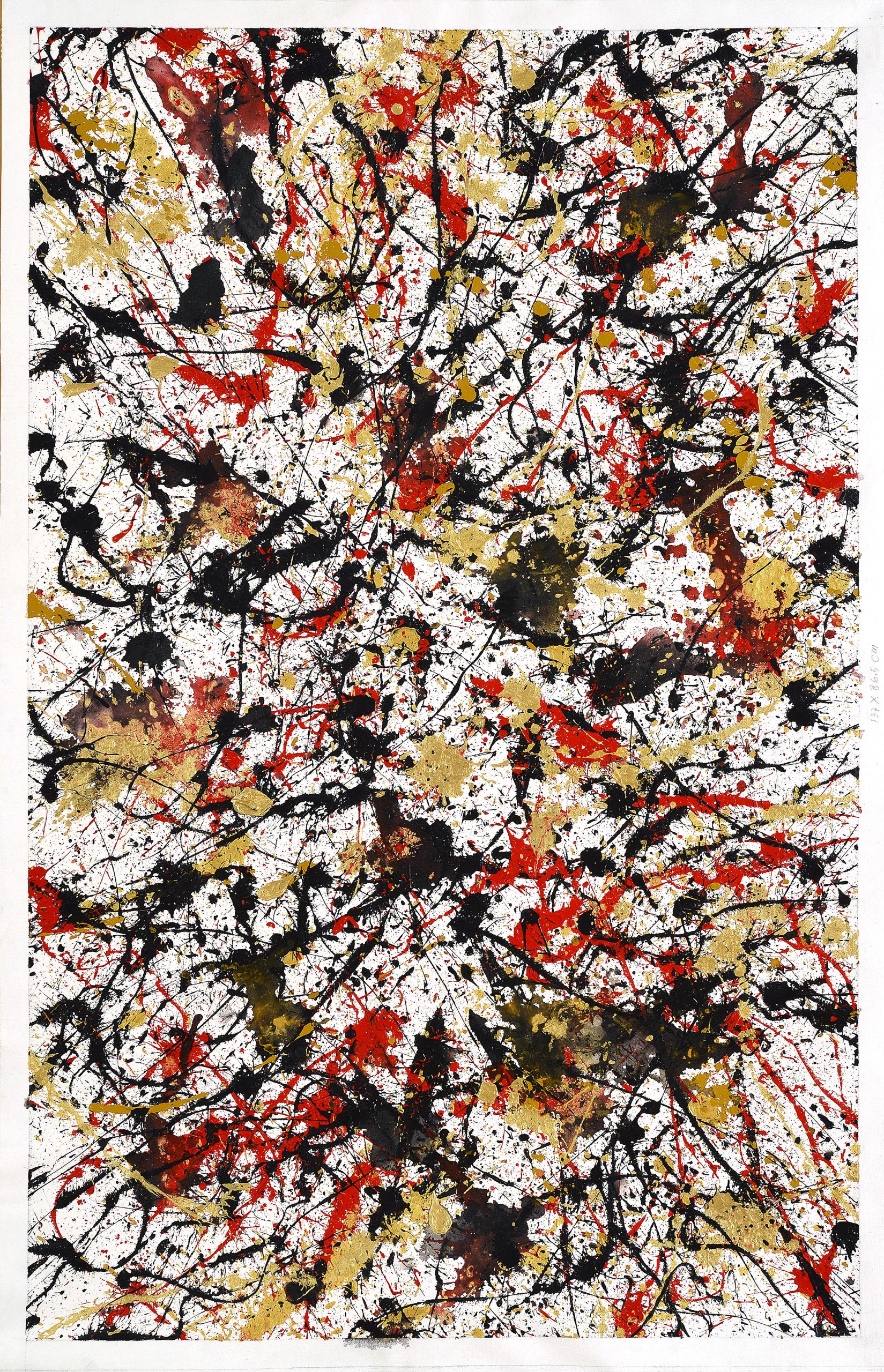

Gede Mahendra Yasa,

Rorschach #1A, 2013.

Acrylic on canvas. 86.5 x 137 cm.

Courtesy of the Artist.

The critic Enin Supriyanto, who describes this disposition as “post Bali,” argues that what Mahendra Yasa seems to ask is this: “What is the meaning of painting today. If all the techniques, materials, styles, as well as iconographies…can be very easily reinstated on a canvas though realism and appropriation without requiring thought processes or subjective aesthetic considerations.”8 In one series, Mahendra surveys the masterpieces of Western art history in the Balinese Pita Maha style of painting which is mobilised to portray landscape. In his Jackson Pollock series in 2011, the abstract expressionism effect is faithfully depicted but in a mode so graphic it negates the gestural impulse of the style; the same is true of his Robert Ryman series in 2008, in which he represents whiteness photorealistically through lower contrast and careful chiaroscuro, not conceptually as object. In the face of this painstaking and elaborate project, we cannot help but wonder about the necessity of labour, and have mixed feelings of sadness and the sublime. Moreover, the aptitude and the diligence reinscribes Balinese as part of contemporary art through the appropriation of the traditional technique and the modernist object of Pollock’s drip or Ryman’s colour: the techniques of depicting flora and landscape transfigure the modernist fixation on the signature gesture and the facture of the inventive object. Alternating in this scheme are repetition and overinvestment, imitation and originality, trace and rigour, tourist art and contemporary art, the found image and the critical image.

In all these forays by Southeast Asian artists, the reflection on art history becomes a reflection on landscape, the evocation of place, its idealisation and corruption in certain discourses of distinction such as: nation, region, spirituality, gender, belongingness to an abode, and its role as refuge in the diaspora. This demystification of landscape ultimately translates into a sense of locality, something that hints at a possibility: that the spectre, or the unconscious, of the contemporary is the local that in turn significantly shapes the history of modernity and continues to haunt the present with the contingency of place, the entry points of modernity, and the histories of art in Southeast Asia.

This paper was developed from a presentation at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo 20th Anniversary Public Symposium titled “To Unravel Our Readings of History,” held at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, November 1, 2014.

Footnotes

1 Elizabeth Mansfield, Art History and Its Institutions: Foundations of a Discipline. n.p. (London: Routledge, 2002) 1-27.

2 In footnote 4 from Seng Yu Jin’s essay, Lim Hak Tai Points a Third Way: Towards a Socially Engaged Art by the Nanyang Artists, 1950s-1960s: There have been competing, and at times confusing, terms used to describe this group of artists (and their artworks) as “Nanyang artists,” “Nanyang School,” “Nanyang art,” “Nanyang movement” and “Nanyang style.” There are nuanced differences in each of these terms. “Nanyang School” implies a loose grouping of artists associated with a particular institution, such as an art academy or society, with a shared stylistic and aesthetic direction discernable in their artworks. “Nanyang movement” is broader than the “Nanyang School” as it suggests a stylistic movement and common aesthetic evident in a group of artists. “Nanyang style” is a much narrower definition based on a specific set of formal qualities that are common in the practices of a group of artists.

3 T.K. Sabapathy, Piyadasa: The Malaysian Series (Kuala Lumpur: Galeri Petronas, 2007) 15.

4 Redza Piyadasa, “The Treatment of the Local Landscape in Modern Malaysian Art, 1930-1931,” Imagining Identities: Narratives in Malaysian Art. Volume 1, eds. Nur Hanim Kairuddin and Beverly Yong (RogueArt: Kuala Lumpur, 2012) 42-43.

5 Suwannakudt, phaptawansuwannakudt.com.

6 Flaudette May Datuin, “The Grid and Nomadic Line in the Art of Phaptawan Suwannakudt,” Contemporary Aesthetics, vol. 3, 2011.

7 Ibid.

8 Enin Supriyanto, “Post Bali,” Post Bali, (Jakarta: Roh Projects, 2014) 4.

References

Datuin, Flaudette May. “The Grid and Nomadic Line in the Art of Phaptawan Suwannakudt.” Contemporary Aesthetics. Vol. 3, 2011. Web.

Mansfield, Elizabeth. Art History and Its Institutions: Foundations of a Discipline. n.p., London: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Piyadasa, Redza. “The Treatment of the Local Landscape in Modern Malaysian Art, 1930-1931.” Imagining Identities: Narratives in Malaysian Art. Volume 1. Eds. Nur Hanim Kairuddin and Beverly Yong. RogueArt: Kuala Lumpur, 2012. Print.

Sabapathy, T.K. Piyadasa: The Malaysian Series. Kuala Lumpur: Galeri Petronas, 2007. Print.

Seng Yu Jin, “Lim Hak Tai Points a Third Way: Towards a Socially Engaged Art by the Nanyang Artists, 1950s-1960s.” Charting Thoughts: Essays on Art in Southeast Asia. Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017. Print.

Supriyanto, Enin. “Post Bali,” Post Bali. Jakarta: Roh Projects, 2014. Print.

Suwannakudt, Phaptawan. phaptawansuwannakudt.com. Web.

Essays

Souvenirs from the Past that Never Was

Souvenirs from the Past that Never Was1

As a phenomenon that implicates memory and perception, warping our sense of space and time in the process, déjà vu – no matter how many times we have experienced it – leaves us puzzled every time. Imagine being in a certain place, taking in the setting and the objects within it, on one hand certain that we have been there previously but, on the other, our instincts signal that we are experiencing this scene for the first time: “I have been in this room before; the table of books with the lamp and the vase are so familiar to me… yet I cannot place when exactly I saw them last.” Our perception insists that there is something that we are trying to recall here, yet our memory tells us that there is nothing in the past that corresponds to what we are seeing in the present. It is this disconnection between perception and memory felt in déja vu that evokes a sense of strangeness and, within that fleeting moment, it is not uncommon that we begin questioning the accuracy of what we perceive and what (we think) we remember.

For the Italian philosopher Paul Virno, the experience of déjà vu, as described above, points to one of its distinct characteristics regarding the nature of the past it implicates. Compare déjà vu, for instance, with remembering the birth date of a loved one: while that date may be recalled with confidence, the time that we try to recollect in déjà vu is ultimately less certain. Thus for Virno, déjà vu is concerned not with the recollection of a “dateable, defined” past that unquestionably occurred in a specific location at a given point in time, but rather a sort of “past in general” that may not have happened at all.2 Characteristic of déjà vu, unlike the memory of past birthday celebrations that is anchored to a specific moment that has gone by, is that it conjures a kind of non-chronological past, a past without a definite position in time. As such, déjà vu is a unique mode of experiencing time.

Another characteristic of déjà vu, as observed by different writers from an Oxford English Dictionary entry of the term,3 points to the sense of familiarity that the experience evokes: the definition of déjà vu states it to be “the correct impression that something has been previously experienced; tedious familiarity…”4 In his book on déjà vu, Peter Krapp notes that such a characteristic of déjà vu is also present in Walter Benjamin’s interpretation on kitsch, a subject that began to be a point of academic reflection by the early 20th century against the backdrop of rampant mass industrialisation and the increasing commodification of art. For Benjamin, the appeal of kitsch – typically mass-produced knick-knacks that decorate the corners of the domestic home – lies in its familiarity. Kitsch objects produce the effect that “this same room and place and this moment and location of the sun must have occurred once before in one’s life,”5 and this sensation matters more than whether or not that past moment had actually occurred. In Benjamin’s account, kitsch makes apparent the familiarity that characterises déjà vu.

In this essay, building from the temporal characteristics of déjà vu as identified by Virno as well as the link between déjà vu, familiarity and kitsch drawn by Benjamin, I wish to extend the discussion by focusing solely on the kitsch objects of souvenirs. While souvenirs typically function as a marker of memory – an “I♠NY” t-shirt as a keepsake from a trip to New York City, for example – I draw attention instead to souvenirs of unvisited places – for instance, a Merlion fridge magnet that may have been bought in Batam without one having been to Singapore at all. While souvenir studies typically focus on its role in embodying the memory of firsthand, lived experiences, I try instead to position the souvenir in terms of the experience of déjà vu as theorised by Virno and Benjamin. To do this, I will refer to an exhibition I co-curated for Singapore Art Week 2016, entitled Fantasy Islands, paying particular attention to its exploration on the issues that surround souvenirs.

I propose that the familiarity evoked by the souvenir is symptomatic of a particular process of staging a national narrative: it is by facilitating an imagination about a place that souvenirs familiarise it. Here, I extend Susan Stewart’s theorisation on the ‘longing’ that souvenirs implicate, by asserting that the souvenirs discussed in this essay present a particular longing for familiarity within the necessarily alienating and foreign dynamics of global tourism. However, in contrast to Stewart’s perspective that longing is a pathological state linked to nostalgia, I see longing as a productive force in its capacity to reveal what Virno refers to as a “potential now.” I conclude by offering the view that souvenirs from places that were never visited make the distinction between nostalgia and déjà vu evident. This essay proposes a way of interpreting souvenirs beyond its usual preoccupation with nostalgia by analysing it according to the framework of déjà vu, thereby emphasising dimensions of the souvenir that are not necessarily tied to the memory of the places that the souvenirs are meant to represent.

“A Past in General” and the “Potential Now”

Discussion about the strangeness of déja vu often revolves around Freud’s theorisation of the phenomenon.6 Like the phenomena of chance encounters and the double, Freud’s déja vu brings us into the realm of the uncanny, where the familiar and the unfamiliar lose their distinction and are seen to be symptomatic of a pathological “compulsion to repeat,” aimed at fulfilling repressed desires. Yet a theoretical framework that pathologises déja vu may not, in fact, prove helpful for the purpose of teasing out what déja vu reveals about concepts that are related to our understanding of time. For instance, it neglects questions regarding the nature of a past that is conjured by déja vu, what it reveals about our constructs of memory, and how this influences our conceptions of history.

For Benjamin, such an experiencing of time – seemingly problematic due to its inherent obscurity – nonetheless plays an important role in the way we understand the workings of history. His interpretation of déjà vu explains to us the relationship between past, present and future that is operative there. In déjà vu, we are transported “unexpectedly” to the past, and while the sensation “affects us like an echo,” “the shock with which a moment enters our consciousness as if already lived through tends to strike us in the form of a sound” occurs simultaneously.7 While this may remind us of Proust’s description of involuntary memory, Peter Szondi and Peter Krapp argue that unlike Proust, whose search for lost time propels him deeper and deeper into the past, Benjamin seeks a connection between the past and the future: whereas Proust preserves the past as impenetrable and inaccessible, Benjamin sees the past as something that unfolds into the future.8 Even though the memory that emerges from déjà vu may be false, it is nonetheless important to consider what kind of future that such a reliving of the past opens toward: “if I have been in this situation, I might know what will happen next; there might be a clue left for me of what is yet to come.”9

This line of argument that gives a specific position to déjà vu in the historical experience – which is conventionally centred on the dynamics of remembrance and forgetting – is pushed further by Virno. He argues, somewhat controversially, that not only is déjà vu not a mere lapse in either memory or perception, it is in fact the very condition for historical possibility. Here, Virno’s argument goes beyond two dominant understandings of history: firstly, that history is an endless quest to put together pieces of the past in the present in order to preempt a vision of the future and secondly, the Nietzschean tradition that sees an active forgetting as necessary for history, because one needs to learn to forget (i.e. be unburdened by the past) in order to move forward. Both, according to Virno, rests on the assumption that any knowledge of the past serves to affirm the now that we are living through. This leads to a danger in the way history is understood, which Virno refers to as “modernariat”, where the endless fragments of the past are gathered solely to affirm and validate what happens in the now.10

According to Virno, what déjà vu reveals is the dual-dimensionality of the now: the “actual now” and the “potential now,” that are being remembered as it is being perceived. As Hiyashi Fujita notes, this conception of déjà vu as both memory and perception is already theorised by Henri Bergson, for whom “the cause of déjà vu is perceiving a certain scene at the same time as recollecting the memory that is currently being perceived.”11 In déjà vu, memory and perception – which in any other experience would remain distinct from one another – becomes entwined; we can no longer maintain that perception is a property of the present moment and memory as that of the past. This two-fold nature of the now that is exposed in déjà vu opens an alternative version of how history may be construed: “learning to experience the memory of the present means to attain the possibility of a fully historical experience.”12

The past conjured by déjà vu may seem false and illusory – and thus easily overlooked – but Virno’s study is instructive in terms of situating its position within a larger consideration of the historical experience.13 Drawing from Bergson, Virno explains that déjà vu summons not a “dateable, defined,” particular past, but a “past in general”, highlighting that, in déjà vu, what matters “is not this or that former present” but rather “a past that has no date and can have none.”14 As déja vu evokes, in the present, a “past that was never actual”, it thus underscores a “potential now” that must not be overlooked in the experience of history.

A Longing for Familiarity

For Susan Stewart, longing is a manifestation of nostalgia, a phenomenon that brings an idealised past into the present and makes it seem more real. In her book, Stewart explains that physically, different forms of longing come to be manifested in the objects of the “miniature, the gigantic, the souvenir and the collection,” and that it is the souvenir, in particular, that signifies the “longing of the place of origin” where the “authentic” – whether experience or object – is encountered.15 As a narrative-generating device, the souvenir creates myths of authenticity: this is no more apparent in an increasingly mediated world where the body no longer becomes the primary mode of perception, and where claims for authenticity are inevitably linked to the articulation of “fictive domains” such as the “antique, the pastoral, the exotic.”16

Focusing solely on the function of the souvenir in embodying the memory of past experiences, for Stewart, the souvenir serves to “authenticate the experience of the viewer.”17 The souvenir, as neither an object of “need or use value,” speaks through a “language of longing” to represent events that are deemed “reportable.”18 Interestingly, Stewart continues to explain the “incompleteness” of the souvenir: first, by being an object that represents an event or experience (e.g. a Big Ben pencil case as a souvenir from a visit to London), and second, it must remain incomplete to allow the supplementation of a “narrative discourse.”19 Specifically, the souvenir generates a narrative of the originary place of the authentic experience, thus simultaneously signifying a nostalgic longing to return to that place and authenticate the memory of having been to that place in the past.

In Stewart’s theory, ‘longing’ is symptomatic of the “social disease of nostalgia,”20 where the present experience of the souvenir is marked by an impossible desire to return to the time where the place symbolised by the souvenir was visited; putting it differently, the “actual now” is characterised by the futile yearning for a “dateable, defined” past. However, in the case of déjà vu, such a past, as the above discussion on Virno’s theory explains, is non-existent: we have never been to that place previously. While Stewart is certainly helpful in explaining the sense of longing that the souvenir embodies, could this longing be felt even in the absence of such firsthand experiences, in the case of souvenirs of places that were never visited? In Virno’s terms, such souvenirs uncover a “potential now” that refer to a “past that was never actual,” in other words: to déjà vu rather than to memory. The question that then needs to be posed is: how does longing operate in déjà vu, in the absence of a past place that may be relived in its memory? If the souvenir is tied to the time of déjà vu rather than memory, then what kind of longing does it manifest – what does it long for?