VOLUME

ISSUE 03

Port of Call

A port of call is a heterotopic site where nautical imaginings contain the mobility of nations, cultures, powers and maritime and economic trade over time. In this issue, art writers, critics and artists reflect and engage with the multiple entries and exits inherent in ports to serve as an aide-memoire to the ancient yet most contemporary of spaces, the port.

ISSUE 03

2014

Port of Call

ISSN : 123456789

Introduction

Essays

Interviews

Photographic Essay

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Port of Call

Essays

Art in the Age of Containers?

ON-ZONE Translated by David Williams

Interviews

Photographic Essay

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy-Editor

Bernhard Platzdasch

Advisor

Milenko Prvacki

Senior Fellow

LASALLE College of the Arts

Manager

Linda Loh

Project Interns

Marilyn Giam

Vanessa Lim Yan Mein

Contributors

Tony Godfrey

Ho Rui An

Ho Tze Nyen

Hou Hanru

James Jack

Lim Kok Boon

Pawit Mahasarinand

Aubrey Mellor

Venka Purushothaman

Bala Starr

Dubravka Ugrešić

Introduction

Introduction: Port of Call

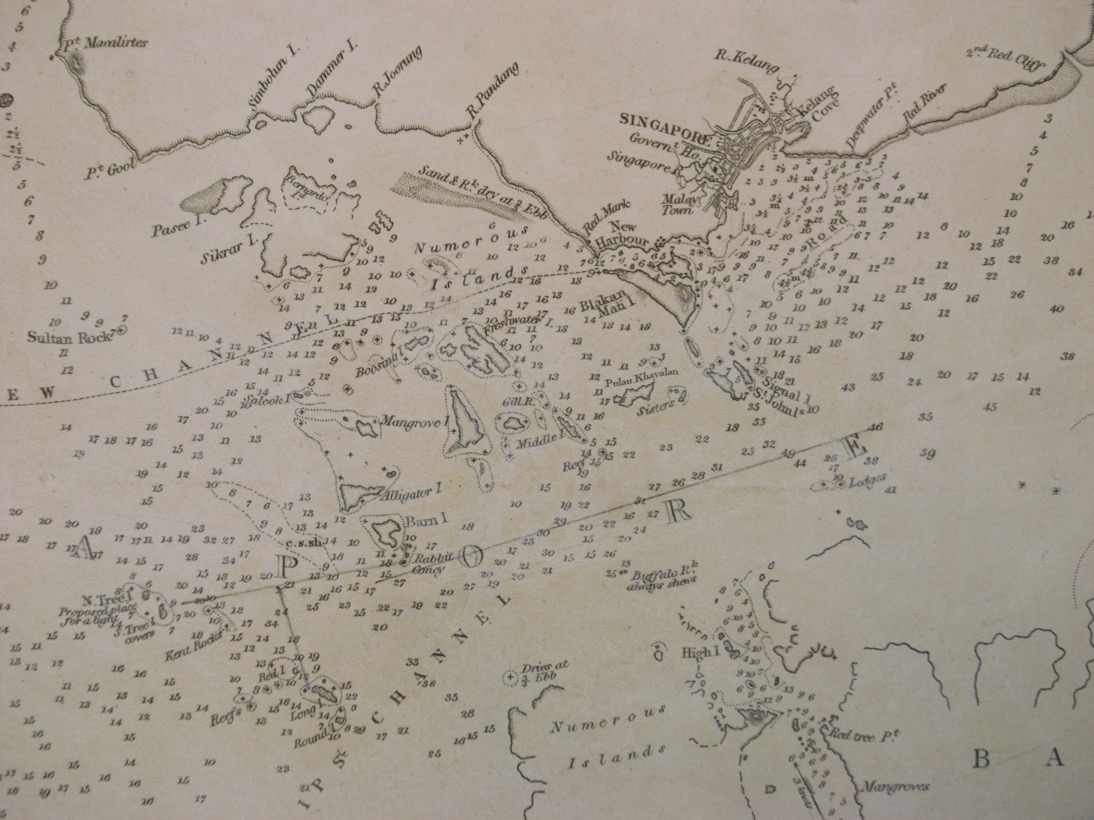

The theme of ISSUE 3 is Port of Call. A port of call is a heterotopic site where nautical imaginings contain the mobility of nations, cultures, powers and maritime and economic trade over time. We know of this only through history, which maps the mobility of nations as geographical drawings onto the carapace of the earth. A port of call is simply a place where a ship anchors temporarily or as a destined final place. But its association reverberates through all other forms of travel (communal, personal, metaphysical and spiritual) including everyday activities indulged by a person. A port of call is also an allegory for a longing to locate oneself through a visit or a return. This longing is wrought with an archeology of hope, remembrance and futility. Both the nautical imagining and the allegory speak resolutely to the human condition.

Often the importance of ports to global trade and the nationhood only becomes apparent in politicised discourse found in foreign relations between nations. Moreover, port cities such as Singapore remain slightly more vigilant as this serves as their lifeline to survive as a nation. While travellers’ tales and political discourse provides us with much fodder for consideration, the symbolic power of the port remains its quiet icon: the container. It symbolises the potent discipline of trade, its impenetrable nature and its containment of consumer fetish. The icon does not move. It is moved. The container masks or silences the inherently heterotopic nature of ports and we are confronted with disciplined and universally objectified systems of organisation.

In this journal we provide a platform to art writers, critics and artists to reflect on the theme. In keeping with the multifarious points of entries and exits inherent in ports, we have attempted a multifocal point through essays, interviews and photography to serve as an aide-mémoire to the ancient, yet most contemporaneous, of sites: the port.

Essays

Global Containers: Containing Visual Arts in the Age of Globalisation

Kublai Khan had noticed that Marco Polo’s cities resembled one another, as if the passage from one to another involved not a journey but a change of elements. Now, from each city Marco described to him, the Great Khan’s mind set out on its own, and after dismantling the city piece by piece, he reconstructed it in other ways, substituting components, shifting them, inverting them.

Italo Calvino

Calvino’s fictive imagination paints a dark possibility as to the way history has framed the world today, which uncannily seems to reinvent itself within the discourse of globalisation. To think of the world in distinct and quantitative cultural composites to be venerated and celebrated and yet waiting to be exploited, re-interpreted and curricularised (as Calvino’s Kublai Khan does) into an international idiom of globalisation is, indeed, odd though true. In this essay, I seek to opine on the adage globalisation and foreground it as an instrument of control, study the manner in which it devours art and find apt responses to these two conundrums in the art of Atta Kim.

I

‘Go global’ is a commonplace maxim. Cross-border exchange of commerce, ideas, peoples, and even disease and terror to any part of the world is at best liquid capital. It is a new world where concepts of time and space narrows with the advent of speedier modes of transport and communications like the Internet. Colonialism exorcised, modernity debunked, there has been increasing pressure on newly industrialising and modernising societies and communities to become viable sites of liberal democratic capitalism.

Globalisation has its roots in seventeenth century industrialisation and became manifestly commandant during the project of colonialism and its attendant, modernism. The establishment of the English language as lingua franca of the world was the first globalised attempt at mono-culturalism (especially for trade, law and education) amidst highly diverse and distinct communities and civilisations. While English remains today the preferred link language of commerce, it carries with it the remains of colonial ideology and continues to be unraveled in emerging socio-cultural discourses and criticism. As modern cities and environments become experiences that cut across all boundaries of geography and ethnicity, of class and nationality, of religion and ideology, the English language unites humankind by organising people into citizens of the world. Perhaps globalisation and modernism are a paradoxical unity of disunity. As Marshal Berman notes, a unity of disunity: “it pours us all into a maelstrom of perpetual disintegration and renewal, of struggle and contradiction, of ambiguity and anguish”. To be modern is to be part of a universe in which as Marx said, “all that is solid melts into air” (1982: 15) Marx’s pronouncement rings true today only to be encapsulated by Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), which chillingly proposes cloning the human at literal and metaphorical levels, and collectivism as a means of enabling a global workforce. In this collectivism, there is no kinship nor reciprocity, only stark human capital.

In this starkness of human capital is there a sense of self? Globalisation erases the volatility of human life and experience through the reduction of geographical distance for shared cross-border socio-economic-political exchange, thereby producing a culture of similarity or sameness. Where then is the sense of self? A feature of modernism was that it proposed a calming of this volatility to find a sense of self. Globalisation risks a claim on this, too, where conflicts between class and ideological forces, emotional and physical forces and individual and social forces are mystified and veneered to reflect a language of uniformity and indifference. Old structures of value systems are subsumed within a framework of free trade marked by mergers and acquisitions. Insidiously, globalisation suppresses the human self and creates a mythic self – one, which is structured on the principles of an exchange-value: A mythic self that congregates at the doorsteps of a global village. The global village (Marshall McLuhan) is nothing more than a utopia of sameness, of dogmatic orthodoxies only to find its allegory in T.S Eliot’s cultural despair of seeing modern life being “spread out against the sky/Like a patient etherized upon a table,” (1998: 3) “uniformly hollow, sterile, flat, one-dimensional, empty of human possibilities”, and which is reliving itself in the global. “Anything that looks like freedom or beauty is really only a screen for more profound enslavement and horror” (Berman 1982: 169-170).

With a certain apocalyptical speculation, Francis Fukuyama (1995) calls globalisation as being representative of the “end of ideology”, that is, an ideology shaped by the locality of a community, in particular, through its kinship, history and reciprocity. The exchange-value structure, premised on free trade, quickened this end together with it any sensibility of a community. In 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall reconstituted this quickening as the world realised issues regarding citizenship were increasingly taking shape. The invention of communication technology and especially the Internet, the communicative symbol par excellence of economic, social, political and cultural free trade has made humans pilgrims, vagabonds, tourists, players, and strollers of the information highway.

Today, the promise of globalisation to a meaningful and ‘beneficial-to-all’ principle is viewed with skepticism as societies awake to the treachery of adhering to universal financial and economic guidelines that negate economic, social and historical specificity: the financial collapse and impact in Indonesia and Argentina in the beginning of the 21st century are a case in point. Anti-globalisation protests have greatly fallen on deaf ears as the blind faith to economic viability as the sole path to human survival and sustainability continues to be guiding light of political systems. The question then is – whose globalisation, whose benefit? The gavel of Wall Street signifies the demise of authority and power of financial economies elsewhere. Wall Street narratives have become the grand recit of globalisation. Despite the collapse of the financial order in Wall Street, the narrative of collapse continues the grand recit in the form of scapes and organizational nodes. Examples of these scapes and nodes include airports, which serve to centralise and control human traffic; stock exchanges, which centralise share and currency trading; international news, which is centralised through agencies such as Associated Press and Reuters; and, search engines such as Google that organise information for consumption. These scapes and nodes control and manage the relay of information and movement of people across national borders, which individual communities are unable to control. Every emergent society wants to be part of this traffic control but these scapes do raise new forms of inequalities (US and European control of major markets); new forms of desires (commodity fetish for US and European products); new forms of risks (increase on surveillance, spread of diseases); and new forms of socialisations (cultural products such as world music and celebrity worship) (Urry 2000: 65). The very notion of ‘society’ is questioned today.

The terrorist bombing of the World Trade Centre (WTC) in New York on 11 Sept 2001, much etched in the human mind, is indeed an attack on globalisation embodied in the lived experience of the WTC and its numerous nationalities working within the semiotic rubric of America. In a Baudrillardian sense, the bombing was nothing more than a simulacrum of the growing concerns of globalisation. As the world viewed the multiple angles and picture frames of the ‘Live from New York’ bombing, the world reveled in its own obscene ecstasy. The event was a baroque opera performed to demonstrate a suffering scion of democracy, of globalisation. Baudrillard’s pronouncement against globalisation was telling. He says,

We are no longer a part of the drama of alienation; we live in the ecstasy of communication. And this ecstasy is obscene. The obscene is what does away with every mirror, every look, every image. The obscene puts an end to every representation. But it is not only the sexual that becomes obscene in pornography; today there is a whole pornography of information and communication, that is to say, of circuits and networks…in their readability, their fluidity, their availability, their regulation, in their forced signification, in their performativity, in their polyvalence, in their free expression (1983: 130-131).

II

In his Lectures on Aesthetics, Hegel declared that the history of art was just a story, and that it had come to an end. He based this in part on the view that art was no longer able to relate society as it once has done…A gap had grown up between society and art, which has increasingly become a subject for intellectual judgement rather than…an object of sensuous and spiritual response.

Arthur C Danto

Art today is both an abstraction and a distraction. As a critique of representational practice in art, the practice of abstraction gained momentum and became the dicta of twentieth and twenty-first centuries employing three-dimensional, performative and multimedia activities to its tenets. Representational practice was held suspect of cultural categorism where it presented, mirrored and stereotyped peoples and ideas. Abstraction was critical, and is still valuable, in propping a palimpsest of ideas and value systems but in recent times has taken serious interrogation as conceptual frivolity and artistry, all in the free-play with nihilism (Nietzsche), the sublime (Kant) and excess (Bataille) referenced themselves into art. Certain totalitarianism has set in and its manifestation was felt in the 2001 Turner Prize award.

Martin Creed’s winning of the 2001 Turner Prize for a minimalist installation work, Lights Going On and Off—an empty gallery centred with flashing lights—as premised on a post-modern diatribe: “people can make of it what they like. I don’t think it is for me to explain it” (BBC News 10 Dec 2001). His win reinforced the growing distension with the path of abstraction. The curators’ response and analysis of the work leaves the view paralysed at best: “his work was emblematic of mortality…what Creed has done is really make minimal art minimal by dematerialising it — removing it from the hectic, commercialised world of capitalist culture. His installation activates the entire space” (BBC New 9 Dec 2001). This does mark a major turning point in the history of contemporary art and the end of imagination could not have been any closer, for many. Abstraction, in its post-structuralist discourse stigmatises localised practices and representational practices as being reductive and unassimilable into the art world despite the fact that representational and figurative works still carry strong collector sentiments in auction houses and galleries.

The development of abstraction, I would argue, has thinned today into notional principles of displaced abstractions that defy locality, embrace psychology, denies identity and promotes universality and celebrates dramatic display of exhibitions. Premised on the post-modern campaign of equality of human life and being, the world today seeks to transcend the cultural, spiritual and socio-political specificity of communities, which have been exposed to harbour biased and fundamental problematics in thinking and application. An internationalist practice has emerged premised on the post-structuralist distrust of authorial intent and the over-reverberance of signifiers in the creation of meanings; and today, painting, I would argue—to borrow Georges Bataille’s words—is a site of trauma, loss and castration (Fer 1997: 3). The castrated abstract art today is one that privileges ‘universal’ aesthetics and concepts over localised ones. This is notable amongst emerging new art markets in third world countries where the need to produce artworks tenable with the expectation of the well-travelled, well-informed tourist whose market gaze is informed by this internationalist standard that is primarily a western discourse. These emergent markets, pushed to the forefront primarily by global economics, negate their own art and historical development.

The rise of art biennales goes in tandem with the global ebb and flow. As a cultural scape of globalisation, art biennales serve as meccas of internationalist practice, where a free-trade emporium or trade fair space earmarks the ideological death of communities as their art is presented in a nexus of ideas and money. From Sydney to Venice, to Dhaka to San Paolo, to New York to Japan, art biennales have registered a powerful scape that manages and sets the international benchmark for art practice through a dramatic display of exhibitory prowess. Biennales are big on international concerns of social matters, aesthetics and meta-narratives, small on local concerns. Identifiable pavilions, booths and signages are the lone representatives of locality and cultural specificity. Any semblance of a localised identity is often, not always, negotiated through the mass cultural appeal of exoticism: Indian, Chinese, African, Andean, Aboriginal iconography have flavoured mass consumption and continues to exert a colonising presence on the native spaces and minds.

In another turn, the emergence of ‘freeports’ for art is disconcerting. A free port is a nexus of trade, which benefits from relaxed custom and excise. Many ports such as Singapore and Hong Kong were founded as free ports during colonialism. Today, Luxembourg, Geneva, Zuerich, Singapore and Bejing are fast becoming freeports or ports of call for storing art not dissimilar to a safe deposit box in a bank. Pioneered by the Swiss, the main attraction unfortunately is antithetical to the purpose of art: to keep valuable art, trapped in private collection and worth billions of dollars, away from public access and scrutiny. In a recent article, The Economist (23 Nov 2013) states:

The world’s rich are increasingly investing in expensive stuff, and ‘freeports’ such Luxembourg’s are becoming their repositories of choice. Their attractions are similar to those offered by offshore financial centres: security and confidentiality, not much scrutiny, the ability for owners to hide behind nominees, and an array of tax advantages. This special treatment is possible because good in freeports are technically in transit, even if in reality the ports are used more and more as permanent home for accumulated wealth.

With prison-like vault security art, fine wine, jewelry, gold and classic cars are cared for in these containers of culture siting in transit between cultures and private and public ownership providing legitimate and much needed comfort and solace to “kleptocrats and tax-dodgers as well as plutocrats.” (23 Nov 2013).

Art in freeports are free from custom duties and taxes as they are primarily in transit from one place to another. However, they can remain in one place for an eternity without attracting taxation and without access to the world. Art today is trapped and boxed within the very structuralist framework that post-structuralism negated and enslaved to a capitalist narrative.

III

The quiet icon of globalisation is the container. Stoic, static and stationed at various ports from Rotterdam to Singapore to Shanghai, the container symbolises the discipline of trade, its impenetrable nature and its containment of consumer fetish. The containers—20 to 40 footers—do not move. They are moved. Prone to abuse, mistrust and piracy, the containers that form a main physical bulk of economic trade for many countries have, at an ontological level, a toughness akin to a human body. The human body as a site of inscription is not new. As a site of divinity and as site of self, the body is marked by instability and indeterminate set of meanings embroiled in a Kantian free-play with authorial narratives that stake claim to power. What than are the inscriptive codes of the globalised world on the body? The containers may provide an answer.

The cultural correlation between the container and the human body are concerns of Korean artist Atta Kim’s grand MUSEUM PROJECT undertaking. Shifting away from a globalised abstraction, Kim’s work resurrect representation through photography, in the Series of Fields, where he presents naked human (Asian/Korean) bodies—trapped, captured, confined, showcased, exhibited, controlled, moved, transported, caricatured—in acrylic boxes. The size of the boxes are uniform and do not allow for much movement. The acrylic boxes are contemporaneous coffins that gain legitimacy by seeking similarity to fetuses found in beakers at science research labs. The bodies are silenced by their nakedness and lack of identity. The boxes of bodies reverberate of museum and anthropological collections that are constantly waiting, waiting to be moved, identified and freed. The transparent boxes are a metaphor for the transparent and invisible control over the human.

Kim suggests several possibilities of freedom. In the #001 Series of Field, Kim presents the alienated containers abandoned on a deserted road. A potentially busy road encounters abandoned boxes of bodies, strategically placed on the road to be run over. An accident leading to freedom is the only possibility here. It reminds one of the trafficking of human refugees left to the mercy of the globalisation’s alter ego: piracy. Yet another freedom is proposed in #003 Series of Field, where boxes of naked bodies are placed at the cosmetic section of a departmental store. Awaiting to be unpacked, freedom for these bodies is through social veneering, that is through cosmetics, to become something other than the freed self. Yet another freedom is starkly crisis-ridden. In #019 Series of Field, nine upright boxes face the ocean. Awaiting to leave for a new identity elsewhere, or were they left behind as rejects, or are they ship-wrecked treasured on an island trapped within the confines of their prejudices, beliefs and value systems? Kim’s work does have far reaching consequences.

In Kim’s works the naked body is central and devoid of inscription and serve to become a manifesto for dead and moving bodies. In actual fact the viewer imposes the inscription. Clothing and nudity have worn themselves out of current practice. Nakedness references itself to the body politic, as the contested terrain for ideas unlike nudity, which still references itself with the body physical. The body today has been removed of its grandiose divinity, linen virginality and quiet sacredness and in place is nexus for value exchange of the commodity culture. Through the fetishisation of a commodity culture, nakedness, in the global world, is nothing more than a cultural veneer that cloaks the horror of assimilation and sameness. Kim’s work emphasises a melange of assimilation and representation. Is the body involved or mute to this writing of globalisation? Is it a writing of enslavement, empowerment, docility, rebellion or virtuosity? This uncertainty could be resolved if we in part accept phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s belief that “experience discloses beneath objective space, in which the body eventually find its place, a primitive spatiality of which experience is merely the outer covering and which merges within the body’s very being. To be the body, is to be tied to a certain world, as we have seen; our body is not primarily in space, it is of it” (1996: 148).

IV

The state of the visual art in the current international practice is nebulous, as the stream of globalisation has overflowed. Rocks in the stream take the shape of economic volatility; tributaries manifest themselves in terrorist activities to stake their right to exist. Caught between a venerated internationalist mode of practice and a jaded traditionalist mode of practice, which has been commodified further as the exotic for mass consumption, contemporary art has become the very structuralist and essentialist principle that is fought against. New visions are needed; a dramatic incident is needed to spur a new awareness. Artists are seeking to return to the habitat, exercising a right to justify a located-ness in the global while the stoic container of the global is still in control.

The original version was published in Site + Sight: Travelling Cultures. Editor. Binghui Huangfu. Earl Lu Gallery: Singapore, 2002 (ISBN 981-04-6706-0). Published with permission from LASALLE College of the Arts. It has been re-edited for this publication by the author. Image from the Collection of Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore, LASALLE published with permission.

Images courtesy of the artist Atta Kim.

References

Baudrillard, Jean. “The Ecstasy of Communication” in The Anti-Aesthetics: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Ed. Hal Foster. Seattle: Bay Press, 1983.

BBC News. “Creed’s Minimal Approach to Art”. 9 Dec 2001.

BBC News. “Creed Lights Up Turner Prize”. 10 Dec 2001.

Berman, Marshall. All that Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

Calvino, Italo. Invisible Cities. New York: Harcourt Books, 1974.

Danto, Arthur C. The Body/Body Problems: Selected Essays. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Elliot, T.S. “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” in The Waste Land and Other Poems. New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

Fer, Briony. On Abstract Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Fukuyama, Francis. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Penguin, 1995.

The Economist. “Freeports: Uber-Warehouses for the Ultra-Rich”. 23 November 2013.

Urry, John. “Global Flows and Global Citizenship” in Democracy, Citizenship and the Global City. Ed. Engin F. Isin. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. Colin Smith. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Essays

Art in the Age of Containers?

Whenever I think of containers I always think of the man I killed in Shanghai. A hundred containers filled with art stacked up on a quayside. I visited Copenhagen in 1996 when it was the European capital of culture. In one exhibition, Art across Oceans: Container 96, ninety-six containers were arranged on a quayside, stacked three high, linked by metal stairs and bridges to maker a “global village”. Each container was given over to an artist from another harbour city to make or display a work in: Beverly Semmes filled hers with a gigantic dress; Richard Torchia made his into a camera obscura, but the one I remember best was that by the Cuban artist Kcho: inside his container was a big wooden box and that was filled with water, and floating on that water was a small, neat dinghy or rowboat. Of course, at one level I knew that his work referenced the many ways Cubans who wished to escape Cuba for a richer life in Florida tried to cross the ninety miles of sea between. (In another exhibition in town, he showed Infinite Column No.5, a work made with inner tyres from trucks and rope, the sort of flotation device the truly desperate had used to get to the land of the free.) But on a more general level the work was profoundly paradoxical: a boat that floated but could go nowhere. Containers are like that too: built to be infinitely transportable, yet incapable of any volition. They are inert.

As a one-time librarian I recognize that a container is like an empty bookshelf: a taxonomic device awaiting taxonomy. But when the library is filled we can see the taxonomy clearly: here is fiction, there is marine biology, there is the history of Singapore. But we can never know the taxonomy of the containers, what is in each, how the types of products are arranged or dispersed—that can only be known by the shipping companies.

Containers nag at me like a bad conscience. Like white plastic shopping bags blowing down the street in the wind they are ubiquitous; like those bags containers are devoid of advertising or any ostensible statement save of ownership: Maersk, Cold Storage, Textainer, Fairprice, Hapag-Lloyd.

Containers made convenient prisons in Lebanon or Afghanistan, and used as such were sometimes left closed until in the oppressive heat all inside had suffocated to death, or else shot inside, the metal walls peppered and punctured by the bullets of machine gun. Inside, in the final silence, brilliantly, sharp shafts of summer sunlight traverse the inner darkness. Containers do not speak of this: they do not speak; they mean nothing. They are solely passive, awaiting use.

KCHO, in Container ‘96, Copenhagen.

In 2005, I went to the Art Basel Miami fair and there amongst all the glitz and ostentatious display of wealth one artist—Kader Attia, a Frenchman of Algerian descent—had been given a container to put art in outside the exhibition hall. He had made a sweatshop shop, filling it as tightly as he could with migrant workers with sowing machines working hard, long hours though unusually, on this occasion for decent wages. He made his point.

Containers were not meant to cause evil: they were invented and developed to tidy up international transport and make the world more efficient—ergo better. They are a convenience that is there to be used. Of course, apart from their phenomenal convenience, they can be used to morally good purpose: When in 1987 Kaspar König was made director of the famous art school in Frankfurt (Städelschule) he insisted that also, for he always curated, he be given an exhibition space but that, in a protest against the museum mania then so gripping West Germany that every city had to have a slick, posh, hyper-modern art museum with a more architecturally radical (and hence more expensive) building than other cities, it would cost less to build than the annual budget for exhibitions. (I doubt, in comparison, that the annual budget for exhibitions at the new National Gallery of Singapore will be a fraction of the cost of the architecture). The architect (female by his choice) constructed a simple top lit box behind the façade of a bombed out library and added for office and storeroom a container on either side. Containers can be used in a poetic, kooky or trendy way: last night I passed by a groovy bar and events venue in Gangnam’s bizarrely called Platoon Kunsthalle—it was made with containers. Shigeru Ban likewise made an elegant gallery for the second Singapore Biennale with containers.

Of course containers are not evil things, they intend no harm, in fact they have no intention or opinion at all: they are passive, ubiquitous and available. Nevertheless they mean many things.

Above all else, perhaps they mean the end of the sailor and at a cultural level the end of the sea. As a child in England like others of my generation, I dreamed of becoming a sailor and travelling the world. Sailors then wore neat uniform with peaked caps and a boy could still aspire to become a sailor and have an exciting life on the ocean waves, a life of adventure, a life of exploration. (Even, we hoped, as we became teenagers, a life with a girl in every port.) But containerisation meant the end of sailors. When Captain Cook sailed these seas, “discovering” Australia in the process, his ship weighed all of 388 tons and needed 71 sailors to keep her moving. 240 years later a large container ship weighs 150 times that, or 450 times when loaded, requires a crew of only 13. It also means the end of dockers, the people who unload ships — like sailors an archetypally male profession. Sea travel is managed now in landlocked offices, on laptops. There is even talk of fully automating ships and doing away entirely with sailors. This bureaucratisation of the sea is typified by Rotterdam and Singapore. Once houses and streets clustered around the port, now the Rotterdam or London docks are far away from the city centre—the Singapore docks soon will be, too. Think of how rarely one seas the sea in Singapore! Nothing save Jumbo seafood restaurant on the East coast seems to actually face the sea.

We English were a nation of sailors, but now are merely a nation of yachtsmen—though one should add yachting, provides a wonderfully physical sensation—scudding across the sea, in a boat so small that you can skim the water with your hand and appreciate the curvature of this world.

At a conference for the first Liverpool Biennale in 1998 Allan Sekula, who was known for his profoundly unromantic photographs of container ships sailing from port to port, talked of how the sea had become uncanny, something repressed, the image still there but no longer experienced as a real thing. His meditations were set off firstly by the Winslow Homer painting Lost on the Grand Banks bought by Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates for more than $30 million – expensive because it was the last major seascape by Homer still in private hands rather than a museum; and secondly, by the recent defeat of the dock workers in Liverpool who had opposed containerisation but after a long and painful labour dispute had all lost their jobs and been replaced by a few technicians with machines to move the containers around instead. “The sea,” Sekula said, “had become uncanny”—it was there in the imagination as a romantic or scary thing—think of movies such as John Carpenter’s The Fog or The Perfect Storm or, squirming at the thought of it, Pirates of the Caribbean. But we didn’t experience it for real any more.

Sea travel is to plane travel as walking is to commute by MRT1—something experiential in space and time against something disengaged and a denial of time. Of course plane flight is real enough, especially when you hit turbulence, but you are no longer anchored, your view of the world is scarcely more real then looking at the world on google earth. Plane travel in comparison to sea travel is like “beam me up Scottie!”

Sea travel is smelly—salt air, oil and fish freshly landed on the quayside. A poetry of departures and arrivals. On a boat one feels the wind in one’s hair, the boat swaying under one’s feet to the lurching rhythms of the waves. One watches the port grow small on the horizon and above the wake gulls call and wheel, waiting for scraps to be thrown.

Sailors were workers, air-hostesses are comforters, their job is to feed you stodgy food you do not need and keep you passive. Being a sailor not so long ago was a mythical sexy vocation —travel then was still romantic and a little dangerous.

All my memories of sea travel are from before the 1980s. A ship taking us to holiday in Jersey and a boat following it out of Portsmouth harbour filled with striking sailors shouting abuse and carrying banners saying “SCABS”. There are not enough sailors to mount a decent strike anymore.

Roaming the ship, watching your home port grow small on the horizon, watching the landscape become one of nothing but boat, water, horizon and sky and in so being becoming aware as never before of how vast and varied both sky and sea with its constant, unrepeating, flux of waves are.

Leaving Plymouth in a force 8 gale: the boat leaning into black, turbulent seas; the passengers bolting their food before running to hide in their cabins. The ship appeared deserted save for my infant daughter and myself, building palaces with Duplo in the play area.

It seems so long ago and presumably most reading this have no equivalent experience: the cruise ships of today are moving dormitories too big to be affected by the waves they move through. You are enclosed in them as in a hotel or in the MRT.

The Twenty-First century is supposed to be one of communication and culture, but it is one where efficiency necessarily rules. A friend of mine who spent his life working in the container industry told me that his firm used to have containers made in Thailand or Indonesia. “We met lovely people, such hospitality, but we could never be sure we would get the containers delivered on time. Now we get them all made in China: we don’t meet such nice people or have such an pleasant time when we go there but we can be sure that the containers will always be delivered on time.”

Sophie Calle. Voir Le Mer. (Room 2, No.5), 2011.

Six years ago I came to live here in what was then the largest port in the world – though now surpassed by Shanghai—but in this city where the docks are so central to the economy I have been on a boat only twice—for a weekend in a resort in Bintan2 and back. Boats are for the very rich (luxury cruises) and the very poor (desperate refugees)—or for containers.

We, as artists and writers, have to reinvent the sea—that is to say rethink what it is now and can be. Nostalgia is pleasant in a melancholy sort of way, but not much use. It is a matter of reconnecting contemporary life and imagination with the communal memory of the preceding ten thousand years when sailing was so common, important and resonant a type of experience.

In a project, Voir le Mer (See the Sea), filmed in 2010 and exhibited during the 2011 Istanbul Biennale, the French artist Sophie Calle took people in Istanbul who had never seen the sea to the seaside and filmed their reactions. (Istanbul is, of course, a port. Anyone who lives there and hasn’t seen the sea must be very poor, buried in the outlying slums). The exhibition consisted of ten videos, each of a person seen from behind looking at the sea. They all eventually turn and stare at the camera. Some seem moved: one old man wipes a tear from his eyes. But generally we are looking at faces. We hear no words. We cannot tell what they are thinking: it is beyond communication. We assume, but do not know, that they feel awe? Or are moved by the beauty of the sea.

Sophie Calle. Voir Le Mer. (View of Bophorus), 2011.

We were, at the same time as viewers, asked to participate in a parallel experience. The museum it was shown in overlooks the Bosphorus—that narrow strip of sea that separates Europe from Asia. A curtain is pulled back in the exhibition rooms: a chair is provided and speakers relay the sound of the sea to that area.

This may all sound a little sentimental, but Calle offset it by in the last room having a group of five children seeing the sea for the first time. They fidget and pinch each other. Obviously they have been told to behave properly. Eventually they have all turned around and are told that it is over. But the camera keeps on running, filming them jumping around in the water, splashing each other and laughing.

And the man I killed in Shanghai? Well not really, or at least not directly, but I bear some responsibility. Some years I had ordered a desk to be made in China—it was cheaper to have it made there and shipped than be made in England—but when it arrived it was broken. The shipper apologized: the container had dropped from the crane in Shanghai. Yes, several other things had been broken – and the man under the container had died, crushed.

Sophie Calle. Voir Le Mer. (View of Bophorus. For some inexplicable reason, all the boats were going one way that day), 2011.

Images courtesy of the author.

Footnotes

1 MRT is Singapore’s Mass Rapid Transit system of public transport.

2 Bintan is part of the Riau islands, Indonesian archipelago, and south of Singapore, about 50 minutes away by boat.

Essays

ON-ZONE Translated by David Williams

Merhan Karimi Nasseri, an Iranian better known as Sir Alfred, lived at Charles de Gaulle Airport from 1998 until 2006, and for much of this time was a kind of tourist attraction. Steven Spielberg’s 2004 film The Terminal was in part inspired by Nasseri’s life story. In contrast to Tom Hanks’ character in the film, Alfred spent most of his time reading. “It’s like a day at the library,” he said.

1.

A few years ago at Bucharest Airport I spotted a sign saying Zona fumatore, which simply means a smoking area, just it sounds way better in Romanian. You see all kinds of zones on your travels: free zones (zona franca), no-go zones, duty-free zones, you name it. West Germans used to call East Germany die Zone, by which they meant the Soviet Zone. There are time zones, erogenous zones, even Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker revolves around a zone. There’s a weight-loss diet called ‘The Zone’, and then you’ve also got zoning, in the sense of urban planning. In sci-fi, a zone is usually some sort of dystopia. Hearing the word ‘zone’, our first association is a clearly defined space, our second, their evanescence. Zones can be erected and dissembled like tents, ephemeral. Last but not least, there’s a form of literary life we might call the out of nation zone, best abbreviated as the ON-zone. I know a person who lives in that zone. That person is me.

I write in the language of a small country. I left that small country twenty years ago in an effort to preserve my right to a literary voice, to defend my writings from the constraints of political, national, ethnic, gender, and other ideological projections. Although true, the explanation rings a little phoney, like a line from an intellectual soap opera. Parenthetically, male literary history is full of such lines, but with men being ‘geniuses’, ‘rebels’, ‘renegades’, ‘visionaries’, intellectual and moral bastions etc., when it comes to intellectual–autobiographical kitsch, they get free passes. People only turn up their noses when it escapes a woman’s lips. Even hip memes like ‘words without borders’ and ‘literature without borders’ ring pretty phoney, too. The important point here is that having crossed the border, I found myself literally in an out-of-nation zone, the implications of which I only figured out much later.

It could be said that I didn’t actually leave my country, but rather, that splitting into six smaller ones, my country, Yugoslavia, left me. My mother tongue was the only baggage I took with me, the only souvenir my country bequeathed me. My spoken language in everyday situations was easy to switch but I was too old for changing my literary language. In a second language I could have written books with a vocabulary of about five hundred words, which is about how many words million-shipping bestsellers have. Unfortunately, my ambitions lay elsewhere. I don’t have any romantic illusions about the irreplaceability of one’s mother tongue, nor have I ever understood the coinage’s etymology. Perhaps this is because my mother was Bulgarian, and Bulgarian her mother tongue. She spoke flawless Croatian though, better than many Croats. On the off chance I did ever have any romantic yearnings, they were destroyed irrevocably almost two decades ago, when Croatian libraries were euphorically purged of non-Croatian books, meaning books by Serbian writers, Croatian ‘traitors’, books by ‘commies’ and ‘Yugoslavs’, books printed in Cyrillic. Mouths buttoned tight, my fellow writers bore witness to a practice that may have been short-lived, but was no less terrifying for it. The orders for the library cleansings came from the Croatian Ministry of Culture. Indeed, if I ever harboured any linguistic romanticism, it was destroyed forever the day Bosnian Serbs set their mortars on the National Library in Sarajevo. Radovan Karadžić, a Sarajevo psychiatrist and poet—a ‘colleague’—led the mission of destruction. Writers ought not forget these things. I haven’t. Which is why I repeat them obsessively. For the majority of writers, a mother tongue and national literature are natural homes, for an “unadjusted” minority, they’re zones of trauma. For such writers, the translation of their work into foreign languages is a kind of refugee shelter. And so translation is for me. In the euphoria of the Croatian ‘bibliocide’, my books also ended up on the scrap heap.

After several years of academic and literary wandering, I set up camp in a small and convivial European country. Both my former and my present literary milieu consider me a ‘foreigner’, each for their own reasons of course. And they’re not far wrong: I am a ‘foreigner’, and I have my reasons. The ON-zone is an unusual place to voluntarily live one’s literary life. Life in the zone is pretty lonely, yet with the suspect joy of a failed suicide, I live with the consequences of a choice that was my own. I write in a language that has split into three—Croatian, Serbian, and Bosnian—but in spite of concerted efforts to will it apart, remains the same language. It’s the language in which war criminals have pled their innocence at the Hague Tribunal for the past twenty years. At some point, the tribunals’ tortured translators came up with an appropriate acronym: BCS (Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian). Understandably, the peoples reduced and retarded by their bloody divorce can’t stand the fact that their language is now just an acronym. So the Croats call it Croatian, the Bosnians Bosnian, the Serbs Serbian, even the Montenegrins have come up with an original name: they call it Montenegrin.

What sane person would want a literary marriage with an evidently traumatised literary personality like me? No one. Maybe the odd translator. Translators keep me alive in literary life. Our marriage is a match between two paupers, our symbolic capital on the stock market of world literature entirely negligible. My admiration for translators is immense, even when they translate the names Ilf and Petrov as the names of Siberian cities. Translators are mostly humble folk. Almost invisible on the literary map, they live quiet lives in the author’s shadow. My empathy with translators stems, at least in part, from my own position on the literary map; I often feel like I’m invisible too. However, translating, even from a small language, is still considered a profession. But writing in a small language, from a literary ‘out-of-nation’ zone, now that is not a profession—that is a diagnosis.

The platitude about literature knowing no borders isn’t one to be believed. Only literatures written in major languages enjoy passport-free travel. Writerly representatives of major literatures travel without papers, a major literature their invisible lettre de noblesse. Writers estranged or self-estranged, exiled or self-exiled from their maternal literatures, they tend to travel on dubious passports. A literary customs officer can, at any time, escort them from the literary train under absolutely any pretext. The estranged or self-estranged female writer is such a rare species she’s barely worth mentioning.

All these reasons help explain my internal neurosis: as an ON–zone writer I always feel obliged to explain my complicated literary passport to an imagined customs officer. And as is always the case when you get into a conversation with a customs officer on unequal footing, ironic multiplications of misunderstandings soon follow. What does it matter, you might say, whether someone is a Croatian, Belgian, or American writer? “Literature knows no borders,” you retort. But it does matter: the difference lies in the reception of the author’s position; it’s in the way an imagined customs officer flicks through one’s passport. And although it would never cross our minds to self-designate so, we readers—we are those customs officers!

Every text is inseparable from its author, and vice versa; it’s just that different authors get different treatment. The difference is whether a text travels together with a male or female author, whether the author belongs to a major or minor literature, writes in a major or minor language; whether a text accompanies a famous or anonymous author, whether the author is young or old, Mongolian or English, Surinamese or Italian, an Arab woman or an American man, a homosexual or a heterosexual... All of these things alter the meaning of a text, help or hinder its circulation.

Let’s imagine for a moment that someone sends me and a fellow writer—let’s call him Dexter—to the North Pole to each write an essay about our trip. Let’s also imagine a coincidence: Dexter and I return from our trip with exactly the same text. Dexter’s position doesn’t require translation, it’s a universal one—Dexter is a representative of Anglo-American letters, the dominant literature of our time. My position will be translated as Balkan, post-Yugoslav, Croatian, and, of course, female. All told, a particular and specific one. My description of the white expanse will be quickly imbued with projected, i.e. invented, content. Customs officers will ask Dexter whether in the white expanse he encountered the metaphysical; astounded that I don’t live at ‘home’, they’ll ask me why I live in Amsterdam, how it is that I, of all people, got sent to the North Pole, and while they’re at it, they’ll inquire how I feel about the development of Croatian eco-feminism. Not bothering to read his work first, they’ll maintain that Dexter is a great writer, and me, not bothering to read my work first either, they’ll declare a kind of literary tourist guide—to the Balkan region, of course; where else?

To be fair, how my text about the North Pole will be received in my former literary community is also a question worth asking. As my encounter with the metaphysical? God no. Croats will ask me how the Croatian diaspora is getting on up there, how I—a Croatian woman—managed to cope in the frozen north, and whether I plunged a Croatian flag into the ice. Actually, in all likelihood my text won’t even be published. With appropriate fanfare they’ll publish Dexter’s. It’ll be called “How a great American writer warmed us to the North Pole.”

That literature knows no borders is just a platitude. But it’s one we need to believe in. Both originals and their translations exist in literature. The life of a translation is inseparable from the relatively stable life of its original, yet the life of a translation is often much more interesting and dramatic. Translations—poor, good, mangled, congenial—have rich lives. A reader’s energy is interwoven in this life; in it are the mass of books that expand, enlighten, and entertain us, that ‘save our lives’; the books whose pages are imbued with our own experiences, our lives, convictions, the times in which we live, all kinds of things.

Many things can be deduced from a translation; and let us not forget, readers are also translators. The Wizard of Oz, for example, was my favourite children’s book. Much later I found out that the book had traveled from the Russian to Yugoslavia and the rest of the East European world, and that it wasn’t written by a certain A. Volkov (who had ‘adapted’ it), but by the American writer Frank L. Baum. The first time I went to Moscow (way back in 1975) I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had turned up in a monochrome Oz, and that I, like Toto, just needed pull to the curtain to reveal a deceit masked by the special effects of totalitarianism. Baum’s innocent arrow pierced the heart of a totalitarian regime in a way the arrows of Soviet dissident literature never could.

Every translation is a miracle of communication, a game of Chinese Whispers, where the word at the start of the chain is inseparable from that which exits the mouth of whomever is at the end. Every translation is not only a multiplication of misunderstandings, but also a multiplication of meanings. Our lungs full, we need to give wind to the journey of texts, to keep a watch out for the eccentrics who send messages in bottles, and the equally eccentric who search for bottles carrying messages; we need to participate in the orgy of communication, even when it seems to those of us sending messages that communication is buried by the din, and thus senseless. Because somewhere on a distant shore a recipient awaits our message. To paraphrase Borges, he or she exists to misunderstand it and transform it into something else.

2.

According to data from the International Organisation for Migration, the number of migrants has increased from 150 million in 2000 to an estimated 214 million today, meaning that migrants make up 3.1 percent of the world’s population. Migrant numbers vary drastically from country to country: in Qatar, 87 per cent of the population are migrants; in the UAE, 70 per cent; Jordan, 46 per cent; in Singapore, 41 per cent. As a percentage, Nigeria, Romania, India, and Indonesia have the lowest numbers of migrants. Women make up 49 percent of the migrant population. Among the migrant population, 27.5 million are categorised as displaced persons, and 15.4 million as refugees. If all migrants were settled in a single state, it would be the fifth most populous in the world, after China, India, the US, and Indonesia, but ahead of Brazil. It’s a fair assumption that in this imagined migrant state, there would be at least a negligible percentage of writers, half of whom would be women.

Writers who have either chosen to live in the ON-zone, or been forced to seek its shelter, need more oxygen than that provided by translations into foreign languages alone. For a full-blooded literary life, such writers need, inter alia, an imaginary library—a context in which their work might be located. Because more often than not, such work floats free in a kind of limbo. The construction of a context—of a literary and theoretical platform, a theoretical raft that might accommodate the dislocated and de-territorialised; the transnational and a-national; cross-cultural and transcultural writers; cosmopolitans, neo-nomads, and literary vagabonds; those who write in ‘adopted’ languages, in newly-acquired languages, in multiple languages, in mother tongues in non-maternal habitats; all those who have voluntarily undergone the process of dispatriation1—much work on the construction of such a context remains.

In Writing Outside the Nation,2 some ten years ago Azade Seyhan attempted to construct a theoretical framework for interpreting literary works written in exile (those of the Turkish diaspora in Germany, for example), works condemned to invisibility within both the cultural context of a writer’s host country (although written in German) and that of his or her abandoned homeland. This theoretical framework was transnational literature. In the intervening years, several new books have appeared,3 and the literary practice of transnational literature has become increasingly rich and diverse. There are ever more young authors writing in the languages of their host countries: some emigrated with their parents, and speak their mother tongue barely or not at all; others (for cultural and pragmatic, or literary and aesthetic reasons) have consciously exchanged their mother tongues for the language of their hosts. Some write in the language of their host countries while retaining the mental blueprint of their mother tongue, giving rise to surprising linguistic melanges; others create defamiliarising effects by mixing the vocabulary of two or sometimes multiple languages. Changes are taking place not only within individual texts, but also in their reception. The phenomenon of literary distancing is one I myself have experienced. Although I still write in the same language, I can’t seem to follow contemporary Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian literature with the ease I once did. I get hung up on things local readers wouldn’t bat an eyelid at. I sense the undertones and nuances differently to how they do, and it makes me wonder about the ‘chemical reaction’ that takes place inside the recipient of a text (in this case, me) when cultural habitat, language, and addressee have all changed. My relationship towards the canonic literary values of the ‘region’ has also changed. Texts I once embraced wholeheartedly now seem laughably weak. My own literary modus changed in the very moment I was invited to write a column for a Dutch newspaper. That was in 1992. I was temporarily in America, war raged in my ‘homeland’, and the addressee of my columns was—a Dutch reader.

I don’t know whether it’s harder to articulate the ON-zone or to live it. Cultural mediators rarely take into account contemporary cultural practice, in which, at least in Europe, ‘direct producers’ co-locate with a sizable cultural bureaucracy—from national institutions and ministries of culture, to European cultural institutions and cultural managers, to the manifold NGOs active in the sector. The cultural bureaucracy is primarily engaged in the protection and promotion of national cultures, in enabling cultural exchange. The bureaucracy writes and adheres to policy that suits its own ends, creating its own cultural platforms, and rarely seeking the opinion of ‘direct producers’. Let’s be frank with each other, in the cultural food chain, ‘direct producers’ have become completely irrelevant. What’s important is that cultural stuff happens, and that it is managed: publishers are important, not writers; galleries and curators are important, not artists; literary festivals are important (events that prove something is happening), not the writers who participate.

Almost every European host country treats its transnational writers the same way it treats its emigrants. The civilised European milieu builds its emigrants residential neighborhoods, here and there making an effort to adapt the urban architecture to the hypothetical tastes of future residents, discrete ‘orientalisation’ a favourite. Many stand in line to offer a warm welcome. Designers such as the Dutch Cindy van den Bremen, for example, design their new Muslim countrywomen modern hijabs—so they’ve got something to wear when they play soccer, tennis, or take a dip at the pool.

The hosts do all kinds of things that they’re ever so proud of, it is never occurring to them that maybe they do so not to pull emigrants out of the ghetto, but rather to subtly keep them there, in the ghetto of their identities and cultures, whatever either might mean to them; to draw an invisible line between us and them, and thus render many social spheres inaccessible. It is for this very same reason that the publishing industry loves ‘exotic’ authors, so long as supply and demand are balanced. Many such authors fall over themselves to ingratiate themselves with publishers—what else can they do? And anyway, why wouldn’t they?

Does transnational literature have its readers? And if it does, who are they? Publishers have long since pandered to the hypothetical tastes of the majority of consumers, and the majority’s tastes will inevitably reject many books as being culturally incomprehensible. If the trend of ‘cultural comprehensibility’—the standardisation of literary taste—continues (and there’s no reason why it won’t), then every conversation about transnational literature is but idle chatter about a literary utopia. And anyway, how do we establish what is authentic, and what a product of market compromise? Our literary tastes, the tastes of literary consumers, have in time also become standardised, self-adjusting to the products offered by the culture industry. Let’s not forget: the mass culture industry takes great care in rearing its consumers. In this respect, transculturality has also been transformed into a commercial trump card. In and of itself, the term bears a positive inflection, but its incorporation in a literary work needn’t be any guarantee of literary quality, which is how it is increasingly deployed in the literary marketplace. Today that marketplace offers a rich vein of such books, almost all well-regarded, and their authors, protected by voguish theoretical terms—hybridity, transnationality, transculturality, postcolonialism, ethnic and gender identities—take out the moral and aesthetic sweepstakes. Here, literary kitsch is shaded by a smoke screen of ostensible political correctness, heady cocktails mixing East and West, Amsterdam Sufis and American housewives, Saharan Bedouins and Austrian feminists, the burqa and Prada, the turban and Armani.

And where are my readers? Who’s going to support me and my little homespun enterprise? In the neoliberal system, of which literature is certainly part and parcel, my shop is doomed to close. And what happens then (as I noted at the beginning) with my right to defend my texts from the constraints of political, national, ethnic, and other ideological projections? My freedom has been eaten by democracy—that’s not actually a bad way to put it. There are, in any case, any number of parks in which I can offer speeches to the birds. What is the quality of a freedom where newspapers are slowly disappearing because they’re not able, so the claim goes, to make a profit; when departments for many literatures are closing, because there aren’t any students (i.e. no profit!); when publishers unceremoniously dump their unprofitable writers, irrespective of whether those writers have won major international awards; when the Greeks have to flog the family silver (one of Apollo’s temples in Athens is rumoured to be going under the hammer); when the Dutch are fine about closing one of the oldest departments for astrophysics in the world (in Utrecht), because it turns out that studying the sun is—unprofitable.

“Things are just a whisker better for you, because like it or not, at least you’ve got a kind of marketing angle. But me, I’m completely invisible, even within my own national literature,” a Dutch writer friend of mine kvetches. And I mumble to myself, Christ, my brand really is a goodie—being “a Croatian writer who lives in Amsterdam” is just the sexiest thing ever. But I understand what my Amsterdam acquaintance is going on about. And really, how does one decide between two professional humiliations—between humiliating invisibility in one’s ‘own’ literary milieu, and humiliating visibility in a ‘foreign’ one? The latter visibility inevitably based on details such as the incongruence between one’s place of birth and one’s place of residence, the colour of one’s skin, or an abandoned homeland that has just suffered a coup d’état. My Dutch acquaintance isn’t far from the truth. Within the context of contemporary Dutch literature, or any other literature, where there is no longer any context; where there is no longer literature; where it is no longer of any importance whatsoever whether anyone reads a book so long as they’re buying them; where it is no longer of any importance whatsoever what people read, as long as they’re reading; where the author is forced into the role of salesperson, promoter, and interpreter of his or her own work; only in such a deeply anti-literary and anti- intellectual context, I am forced to feel lucky to be noticed as a “Croatian writer who lives in Amsterdam,” and what’s more, to be envied for it.

By now it should be obvious, the little pothole I overlooked when I abandoned my ‘national’ literature is the sinkhole of the market. Times have certainly changed since I exited the ‘national’ zone and entered my ON-zone. What was then a gesture of resistance is today barely understood by anyone. (Today, at least in Europe, recidivist nationalisms and neo-fascisms are dismissed as temporary, isolated phenomena.) Of course, not all changes are immediately apparent: the cultural landscape remains the same, we’re still surrounded by the things that were once and are still evidence of our raison d’être. We’re still surrounded by bookshops, although in recent years we’ve noticed that the selection of books has petrified, that the same books by the same authors stand displayed in the same spots for years on end, as if bookshops are but a front, camouflage for a parallel purpose. The officer in charge has done everything he should have, just forgotten to periodically swap the selection of books, make things look convincing. Libraries are still around too, although there are less of them: some shut with tears and a wail, others with a slam, and then there are those that refuse to go down without a fight, and so people organise petitions. Literary theorists, critics, the professoriate, readers, they’re all still here; sure, there aren’t many of them, but still enough to make being a writer somewhat sensical. Publishers, editors, agents, they’re all still in the room, though more and more often it occurs to us that they’re not the same people anymore. It’s as if no one really knows whether they’re dead, or if it’s us who’re dead, just no one’s gotten around to telling us. We’ve missed the boat on heaps of stuff. It’s like we’ve turned up at a party, invitation safely in hand, but for some reason it’s the dress code all wrong.

Literary life in the ON-zone seems to have lost any real sense. The ethical imperatives that once drove writers, intellectuals, and artists to ‘dispatriation’ have in the meantime lost their value in the marketplace of ideas. The most frequent reasons for artistic and intellectual protest—fascism, nationalism, xenophobia, religious fundamentalism, political dictatorship, human rights violations, and the like—have been perverted by the voraciousness of the market, stripped of any ideological impetus and imbued with marketing clout, pathologising even the most untainted ‘struggle for freedom’, and transforming it into a struggle for commercial prestige.4

For this reason it’s completely irrelevant whether tomorrow I leave my ON-zone and return ‘home’, whether I set up shop somewhere else, or whether I stay where I am. For the first time I can see that my zone is just a ragged tent erected between the giant tower blocks of a new corporate culture. Although my books and the recognition they have received serve to confirm my professional status, they offer me no protection from the feeling that I’ve lost my ‘profession’, not to mention my right to a ‘profession’. I’m not alone, there are many like me. Many of us, without having noticed, have become homeless: for a quick buck, others, more powerful, have set the wrecking ball on our house.

Let’s horse around for a moment—let’s take the global success of E.L. James’s 50 Shades of Grey seriously (you can’t not take those millions of copies sold seriously!), and baldly assert that the novel is the symbolic crown of today’s corporate culture. And if we read the novel as exemplary of corporate culture—financial power as the only currency; the anonymous commutability of the surrounding class of ‘oppressed’ chauffeurs, secretaries and cooks who serve Christian and Anastasia; sado-masochism as the organising principle of interpersonal relations in all domains, including sex; brutality, vulgarity, violence, materialism; people being either masters or slaves— there’s no chance of us missing a particular detail. At one point Christian gives Anastasia an ‘independent’ (naturally!) publishing house as a little present. And thus, in this symbolic setting, my literary fate (and the fates of many of my brothers and sisters of the pen) depends entirely on the symbolic pairing of Anastasia and Christian. In this kind of setting, indentured by the principle of publish or perish, I belong to the servant class and can only count on employment as Anatasia and Christian’s shoe-shine girl. And so it is my spit that softens their shoes, my tongue that licks them clean, my hair that makes them gleam.

Lamenting the death of the golden era of critical theory, Terry Eagleton memorably observes: “It seemed that God was not a structuralist.” But it seems that God was not a writer either, certainly not a serious one. He slapped his bestseller together in seven days. And this all gets me thinking—if I’ve already bet my lot in life on literary values and lost—maybe I should bet my few remaining chips on their future. Because who knows, perhaps tomorrow, on my every flight of fancy, a translucent book, letters shimmering like plankton, will appear in the air before me; a liquid book into which I’ll dive as if into a welcoming sea, surfacing with texts translucent and alive like a shoal of sardines. Perhaps tomorrow books will appear whose letters will converge in the air like swarms of gnats, with every stroke of my finger a coherent cluster of words forming. It’s not so bad, I think, and imagine how in the very heart of defeat a new text is being born.

Footnotes

1 “By dispatriation I mean the process of distancing oneself more from one’s own native or primary culture then from one’s own national identity, even if, as we have seen, in a many cases the two tend to coincide.” Arianna Dagnino, “Transnational Writers and Transcultural Literature in the Age of Global Modernity,” Transnational Literature, 4.2 (May 2012).

2 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

3 In addition to Seyhan’s book, worth recommending are the edited collection Transnationalism and Resistance: Experience and Experiment in Women’s Writing, edited by Adele Parker and Stephenie Young (Rodopi, 2013), and the collections, The Creolization of Theory (Duke UP, 2011), and Minor Transnationalism (Duke UP, 2005), edited by Françoise Lionnet, and Shu-mei Shih respectively.

4 In May 2013, the nationalist Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) launched its election campaign wearing a new ‘party’ dress. In place of the usual checkerboard coat of arms, gingerbread hearts, circle dances, and similar down-home kitsch, these Croatian rednecks came out with minimalist posters bearing Jean Paul Sartre’s “It is right to rebel!” slogan— poor old Sartre the ideological plume of Croatian conservatives!

Essays

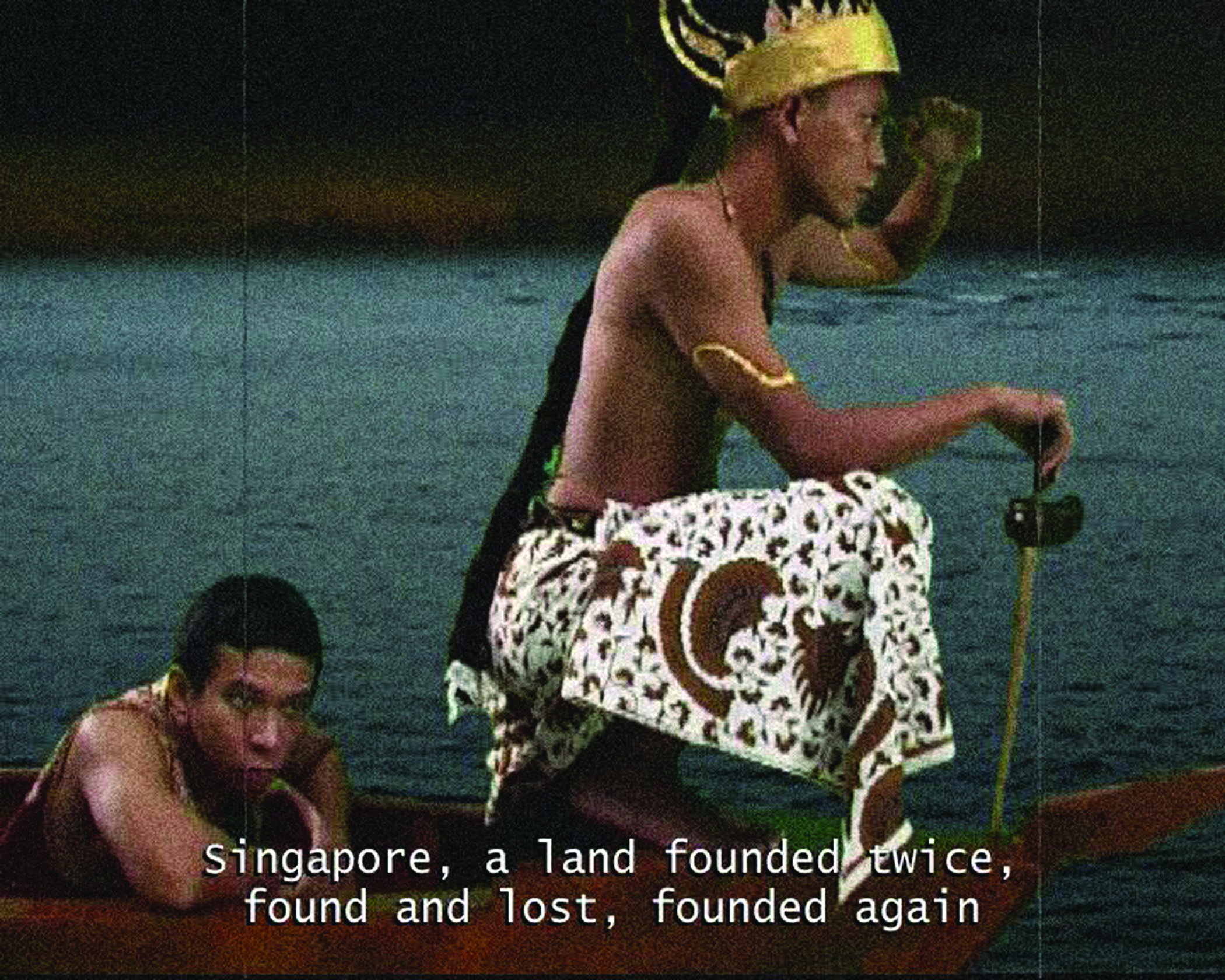

Since Singapore gained independence in 1965, its economic, social and educational headways have stood out on the world stage, worthy of study by politicians, economists, sociologies, and educators alike. Yet its national and cultural identity is often called to question. Given its diverse immigrant historical cultural hinterlands far and wide, this young nation’s population composite is unsurprisingly inhomogeneous and mixed. Different artists have dealt with the situated complexities of identity and culture through different art forms and distinct styles.

Artist-photographer John Clang’s solo exhibition is one such interjection in this on-going discourse, bringing photographic representation and facet of Singaporean families to the spotlight. The ‘Family’ is widely accepted as the basic building block of the community, society and nation and is a theme Singaporeans are concerned about.

Being Together: Family & Portraits (2010), a grand solo exhibition by John Clang can be appreciated in two ways: first, as a lucid exposition on Singaporean identity and family relationships in the context of globalisation; second, as a loaded and engaging de-construct of the family portraiture genre in the light of burgeoning demand for image-making tools in a media hungry society. The photography style of Clang is unmistakable.

Being Together (Family), 2010, Fine art archival print, 40 X 60 inches

It is raw, divulging and compelling for a second look.

The five series in the exhibition are sentimental on many levels. Named Being Together, The Moment, Fear of Losing the Existence, Guilt and Erasurem are clearly portraitures of Singaporeans. As the curator for this exhibition Szan Tan aptly summarised: “Clang emphasizes the profound ordinariness of a family portrait for each depicted moment is ultimately to unite and not to idealize, glorify or celebrate, unlike traditional studio portraits… The simultaneous feeling of being part of and yet physically apart from one’s family is precisely what Clang had hoped to achieve.”

A tiny scribbled Confucius text on the wall suggests the personal significance of Clang’s reunion portraiture technique. The text, written in Mandarin1, loosely implies and translates as “If travel is a must, there must be a reason”. This refers to the personal responsibilities the artist has towards his own parents, and his temporary relocation overseas is a justified endeavour. The quote is an emblem of filial piety, a strongly held core value in Asian culture, as well as implying the concern parents may have when their children travel. From this text, we can feel the personal mission of Clang’s portrait series, as a means of connecting with his own parents and brother based in Singapore while he worked in New York. In this exhibition, he merely extended his photographic methodology to bring other people separated by distance and time zones together.

Being Together is the most extensive series out of five in the solo exhibition. It combines the warm, fuzzy, feeling we have towards taking family portraits with our fascination with communication technology. The photographs in this series show a family member and immediate kin standing or seated in a darkened room, against a projected Skype image of his or her family. From the title of each photograph, we know one party is abroad and the other lives in Singapore. Why the family members are separated by distance is not immediately known. From the homely furnishing, the viewer might infer rewarding circumstances as pull factors: for work, study, or extensive sojourning. The viewer might be able to tell the social status of the sitters from the objects and furniture in the photograph and projected image. Likewise, the body language of the sitters might well reflect their thoughts, feelings, and kinship ties to other people in the image.

The habit and venture of taking family portraits is not unfamiliar to a Singapore audience. It can be an ordinary and casual snapshot against a perfectly banal scene, or an elaborate constructed studio photograph. Most Singapore households may have one hanging or displayed in the living room, bedroom, or communal place at home. Photographic portraits depicting newlyweds, children, family members or friends are common. Anecdotally, If there was a hierarchy for portraits, the family portrait might rank highly because it is displayed more so than other photographs. Quite simply, family portraits express family ties, close relationships, personal histories, and treasured stories about one’s family and their lives. If one wanted to be cynical then these family photographs portray how the families want to be seen—happy, idealized.

The images by Clang in this series are unsettling in three ways. First, the shadow cast by the figure nearest to the photographer disrupts the image, bringing attention to a suggested ruptured distance between the people in the photographs. Second, the blurriness of the figures, what is sharper, clearer or nearer to the photographer, implies a visual hierarchy. The (distant) background becomes a wispy connection with the foreground, marking the separation starkly. The image (and photographer) becomes a witness to a forlorn attempt to reunite family members in a virtual space. Third, it reveals our assumption of and value for a typical family structure in Singapore: parents with children or best with grandchildren.

Being Together - Toh Family (New York, Los Angeles, Yio Chu Kang), 2012.

The photographs in this series plausibly represent family reunions for many Singaporeans in the near future. As Singapore embraces globalization, just as how its immigrant forefathers had, it would be soon be easy to find relatives working at some point in time in another part of the world. How exotic those locations depend on their appetite for adventure, opportunities or dire circumstances. These reunions are as real as they are, enabled by Internet video conferencing technology. If we want to, we can be emotionally connected to a person talking on the other end of a telephone call despite the distance. Conversely, the advent of smart phones might well have crippled our face-to-face communication skills, or introduced a poor excuse not to hold conversations with love ones sitting next to each other. Thus one could argue that the artist’s use of Skype in this photographic series is an acknowledgement of the evolving family nucleus2 in Singapore and their dependence on Internet-based communication technology to converse. If Singaporeans want to keep a particular standard and way of living evident in the photographs, they might have to travel, sojourn or relocate with their family or venture out alone. The Internet would be an important communication conduit to stay connected. The Internet is the port of call wherever we are.

The family is also the subject matter in The Moment series. Accordingly to Clang, this series explores a moment of family members being photographed together. He was interested in revealing the underlying ease or tension within “family hierarchies, gendered roles and inter-generational relationships”. Each triptych reveals a different family dynamic. In this series, each family is photographed from different viewpoints, like a “time-spliced” montage. The edges of the triptych photographs cruelly crop the sitters, resulting in an uneasy triptych picture. If photographs capture a certain truth about its subject, this presentation is more telling about the sitters. As a series, the concept of an idealized happy family is called to question. The individuality of the sitters might be revealed or concealed by their poses and body language: Is that a genuine smile or a deliberate wry one? Are the hands open and receptive, or tensed and clenched? Is the awkward cropping omitting something in order for our imaginations to fill in?

Assuming photographs can be read like texts, Clang’s photographic gesture and methodologies in both Being Together and Moment Series might be perceived as a deconstruction of the idea of a family. The family is often considered the most basic and universal construct in a society. The idea of the family can be considered important from cultural, moral, economical, religious and sociological perspectives. Any changes to these perspectives and values would change how we view the importance of a family as a way of life. According to the Singapore Department of Statistics, there are six household living arrangements3 that are quite telling of Singapore’s evolving family nucleus and living arrangements. Household living arrangements have evolved over the years in tandem with changes in the population’s life style, age structure as well as marriage and family formation preferences. The number of couple-based households with children declined from 66 per cent in 1990 to 56 per cent in 2010; correspondingly, couple-based households without children increased from 8.4 per cent to 14 per cent in 2010 while living alone households increased from 5.2 per cent to 12 per cent in 2010. These figures are consistent with population consensus figures on Singapore’s falling birth rate and increasing number of Singaporeans who chose to remain unmarried. By dissecting and fragmenting an image, we we might begin to see this as symbolising a fragmenting family structure.

The Moment, 2011-2012. Courtesy of the artist John Clang.