VOLUME

ISSUE 14

Service

This ISSUE presents ways in which artists, writers, and scholars reimagine and broaden the idea of service. Ultimately, the aim is not to resolve the inherent ambivalence of service but to illuminate it.

ISSUE 14

2025

Service

ISSN : 2315-4802

e-ISSN : 3041-0924

Introduction

Exhibition

Essays

Conversation

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Ambivalent Service

Exhibition

Beyond Service: Reimagining Care, Autonomy, and Exchange in Artistic Projects

Essays

Divine Inspiration: The Art of Service

Service—“Don’t Teach Art”

Conversation

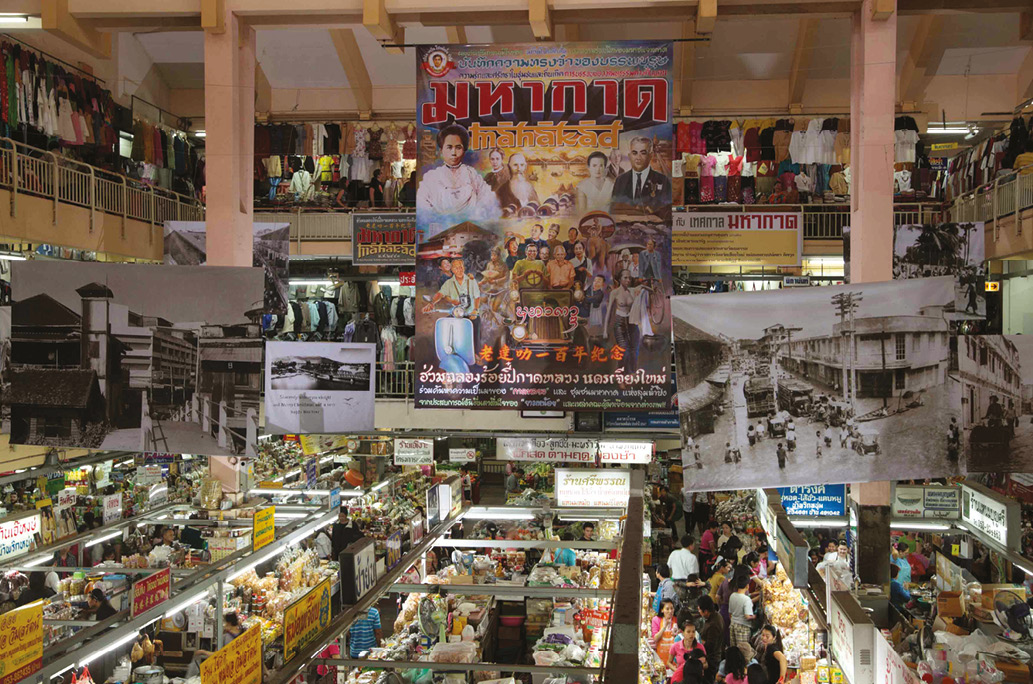

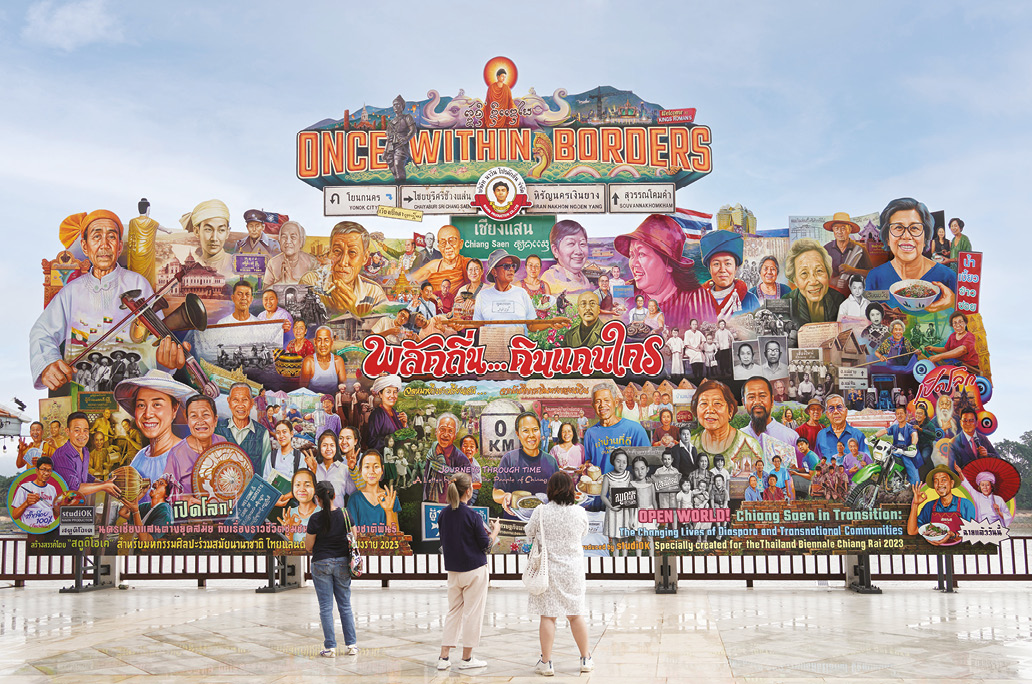

Chiang Mai: Service and relationality in art practice

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy editor

Weixin Quek Chong

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Editorial Board

Asst Professor. Felipe Cervera, Theatre and Performance Studies, University of California Los Angeles

Professor Patrick Flores, University of the Philippines

Dr. Peter Hill, Artist and Honorary Enterprise Professor at the Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne

Professor Janis Jefferies, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK

Dr. Charles Merewether, Art Historian, Independent Researcher, Curator and Scholar

Editorial and Publication Support Team

Dr Malar Nadeson, Dr. Darren Moore, Sureni Salgadoe

Contributors

Tamares Goh

Irfan Hošić

Denise Jambore

Dev Nath Pathak

Ute Meta Bauer and Ng Mei Jia

The editors and editorial board thank all reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments and feedback to the contributors.

Introduction

Introduction: Ambivalent Service

In recent years, scholarly and practical attention to service has expanded far beyond traditional confines to social welfare and public administration. As both an analytic enquiry and lived practice, the idea of service today challenges us to interrogate the underlying presumptions of our commitment to one another, whether as citizens, consumers, professionals, or creative practitioners. Service as a field of inquiry is fertile, not least because of global disruptions that have laid bare the manifold ways service sustains and fragments societies as a complex nexus of ethics, emotion, infrastructure, and power.

At its most fundamental level, service connotes helping or being present. To serve is to engage in selfless action, to sacrifice—or at least defer—one’s needs to those in need. As a humanitarian ideal, service expresses empathy, respect, and care. Yet service, beyond this primal ideal, is situated within broader complex social, political, and economic systems that nurture and confine it.

To unravel the complexity of service, it is helpful to distinguish between two interrelated dimensions: affect and effect. ‘Affect’ refers to the emotional, embodied presence that service providers bring to their work. Be it the empathetic gaze of a nurse, the listening ear of a teacher, or the committed labour of volunteers, these gestural utterances presuppose care and imprint themselves on both giver and receiver, generating human connectivity, providing a sense of security and safety. The affective dimension underscores service as an enactment of shared humanity, where personal vulnerability and professional discipline converge.

Yet service also possesses an ‘effect’: an instrumentalised role in governance and economic systems, inseparable from hard and soft infrastructures. Hard infrastructure comprises the tangible structures and facilities, such as schools, hospitals, and transport systems, that scaffold public service delivery. Soft infrastructure, conversely, encompasses the policies, norms, and bureaucratic procedures that determine and govern who benefits from the rendered service and under what kinds of conditions and expectations. It becomes a tool of governmentality as to how one is governed and who governs.

In contemporary societies, the oscillation between affect and effect highlights equity, agency and upliftment concerns. Global and local conditions may inform who benefits, thereby underscoring the transactionalised nature of service in everyday life, blurring the line between humanitarian service and public service. Against this backdrop, it becomes imperative to reconsider the ways in which service might be reimagined or reclaimed.

One fertile site for such inquiry is the arts. In the twentieth century, arts institutions and practitioners increasingly articulated their work in terms of service to communities, whether through participatory theatre, public art commissions, community music projects, or socially engaged design. This turn recognised the arts as both objects of aesthetic appreciation and as agents of social cohesion, critical reflection, and collective empowerment.

But there is a tension. While artistic practices can amplify and provide space for marginalised voices, foster intercultural dialogue, and catalyse civic participation, their aesthetic and creative dimensions can also be instrumentalised for urban redevelopment and gentrification agendas, tourism strategies, corporate sponsorships, or assuaging political tensions.

This ISSUE presents ways in which artists, writers, and scholars reimagine and broaden the idea of service. Ultimately, the aim is not to resolve the inherent ambivalence of service but to illuminate it.

Exhibition

Beyond Service: Reimagining Care, Autonomy, and Exchange in Artistic Projects

Service, in its early usage, denoted an unequal power structure, derived from the Latin servitium, meaning “slavery” and implying subjugation. In Hegel’s Master-Slave dialectic, the two exist in mutual dependence, yet the slave’s autonomy is denied by the master.1 The term has, over time, taken on a more constructive meaning, though not without its fallacies and conundrums. This is evident in the canon of associated fields and institutions, from healthcare services and social work to hospitality, and, more recently, ecosystem services. For the latter, it operates as a method of quantification, assigning monetary value to the essential contributions and benefits of natural environments to human well-being, quality of life, and survival—one of the many methods deemed unavoidable to justify the existence of the more-than-human in an economy that prioritises profit maximisation. Power thus shapes spaces and people; even as epochs shift, service provisions continue to operate within a capitalistic model, extending conditions rooted in colonial histories. Yet in the spirit of resistance, artists and cultural producers strive to be autonomous agents, in no one’s service—as philosopher Antonio Gramsci would posit them—organic intellectuals, crucial in challenging prevailing hegemonies and shaping the cultural landscape.2

Human and more-than-human species do not exist in isolation. Despite fraught ways of living and being that encourage individualistic behaviours and reinforce power imbalances, we live a shared life—dense and plural in experiences—and cope together in structures of society and in a natural environment.3 This is a basic fact of existence. Yet, service within this line of thought should not be construed as fundamentally altruistic. Political theorist Emma Saunders-Hastings argues that the promotion of humanitarian efforts or the pursuit of one’s conception of good risks being paternalistic, and that is not necessarily grounded in the social and political relations that foreground reciprocity, trust, and respect for all autonomous agents.4 By way of illustration, within the structure of the present-day healthcare system, patients are addressed first and foremost as customers.5 “How can I help you today?”—a question all too familiar, relatable, shifts the responsibility of care back to the patient, who must first decide if they are unwell and locate physiologically where they experientially feel ill. It is thus compelling to begin thinking with and through posthuman thinkers such as Donna Haraway6, Anna Tsing7, María Puig de la Bellacasa8, and many others, in distributing agency and decentering the human subject, to enact an ethics (of care) not in a formulaic way that reinforces individualisation and monocultural thinking, but by building towards an orchestra of diversity, drawing from collective affairs to the personal entanglements and collaboration of all living things and species in the practice of everyday mutual care. In dismantling power hierarchies and thinking through relationships, transforming service from a world shaped by economics into one that “takes care of one another” becomes a process of reinstating autonomy, voice, and knowledge for the inequitable, the silenced, and the marginalised. Such a shift reverses the power dynamic, in which today’s so-called service providers—still entrenched in old paternalistic ways—can be epistemically transformed. This would foster a sense of cultural openness, encourage dialogical happenings, to imagine and construct alternative sets of beliefs, values and motivations and model new ways of being together in a world.

Artistic practices, without superimposing on art or cultural production as a social good, have long been versed in and attuned to making critical interventions or responses spurred by their particular surroundings. Resources obtained from increasingly privatised cultural and academic institutions, through commissioned works or other means, are utilised or distributed to artists’ interlocutors to build the foundation for a sustainable mode of working and living. The complex networks of exchange threaded by artistic operations, which cut across the different modalities of service, enable the amplification of rising concerns, realising the potential these efforts can effectuate beyond an individual. It follows the logical flow that shared responsibility can galvanise and translate into agency. Ranging across spatial dimensions—from land to sea—to the social dimensions of education and mutual aid alliances and structures, this issue expands the discussion through the proposal of keywords: community, collectivity, exchange, guardianship, ownership, accountability, and advocacy. An initial conception from the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, After Rain, the introduction of the keywords allows for a rethinking of the language that engenders a constellation of care beyond service, an approach Spanish philosopher Paul B. Preciado considers critical in acting as a solvent for normative frameworks. This issue profiles artistic practices to unfold what constitutes a sustainable provision of care, highlighting the crucial role artists and their works play in speaking to and with those who feel unseen, overlooked, or displaced, as well as to their communities, in fostering a critical collective consciousness in society.

Collectivity

In an era of turbulent times—when violence, both slow and immediate, subtle and physical, persists; when information communicated through the digital realm becomes overwhelming, causing desensitisation or perplexity in the face of inaction—the informal organisation of enduring resistance, framed as a basis for cooperation, mutual support and solidarity, foregrounds a shared emotional labour in navigating and standing firm against the dominant systems that contribute to festering planetary degradation. Coming together, and the act of doing things together—whether through shared experiences of festivities, celebrations, ceremonies, or the often-overlooked everyday act of sharing food and time in communal settings—are experiences that connect us with one another and engenders encounters that transform ordinary gestures into acts of care and quiet defiance. Such gatherings can activate passive networks into more permanent active ones, forming social relations nourished by trust, a shared identity and the commitment to collective well-being. Resource sharing and creative solutions are mobilised to regain the commons. As an affective practice, the communal sharing of food, for instance, nurtures bond, preserves memory, and foster possibilities for mutual sustenance and reflection.

BRITTO ARTS TRUST

Palan & Pakghor (The Kitchen Garden & The Social Kitchen), 2024

Defined by the structures of Bengali palan and pakghor, the palan is a traditional kitchen garden, often tended by women and children, which supplies the pakghor, a family kitchen akin to a living room. Developed for and during documenta fifteen, Britto’s pakghor served food and gathered people of various nationalities residing in Kassel. They prepared meals, shared their histories and memories, and hosted events that presented food cultures of 100 nationalities over the course of 100 days. A further iteration of the project took shape at the 2024 Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, where the palan grew vegetables and culinary herbs supplied by Alzahrani Farm in Diriyah, while the pakghor was activated by volunteers from across Riyadh. Centred on cooking traditions, the social space offered stories and moments for reflection on cultural identity and difference in a rapidly changing urban environment.

Palan & Pakghor (The Kitchen Garden & The Social Kitchen), social space for cooking and gathering, 2024.

Britto Arts Trust, Palan & Pakghor (The Kitchen Garden & The Social Kitchen), 2024, installation view at After Rain, Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale. Photo by Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Britto Arts Trust, Palan & Pakghor (The Kitchen Garden & The Social Kitchen), 2024, installation view at After Rain, Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale. Photo by Marco Cappelletti. Courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

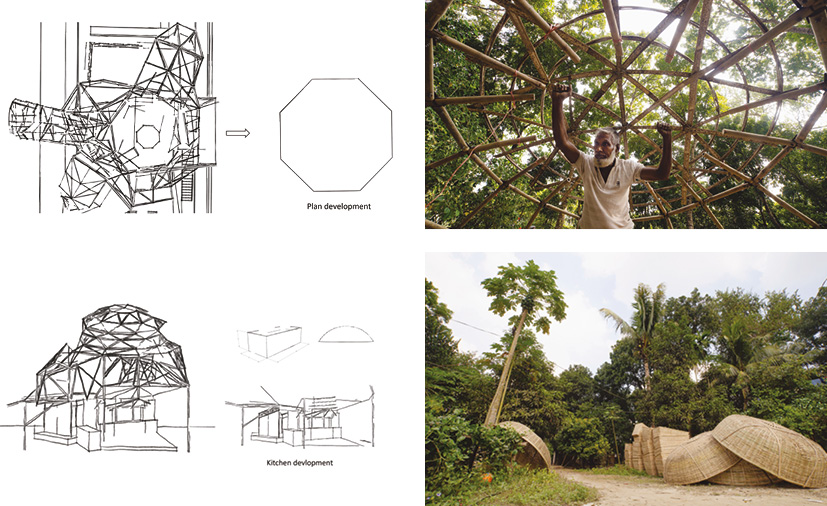

Pakghor design-development phase, Studio Mahbub & Lipi, Hasnabad, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2023. Britto Arts Trust. Palan & Pakghor (The Kitchen Garden & The Social Kitchen), 2024.

Top: Local artisan making the dome of the pakghor (family kitchen), Manikganj, Bangladesh, 2023.

Bottom: Handcrafted bamboo baskets and objects woven by the artisans of Manikganj. Britto Arts Trust. Palan & Pakghor (The Kitchen Garden & The Social Kitchen), 2024.

Construction collaboration with the community to design and build a library / conflict resolution space. Alexander Eriksson Furunes & Sudarshan Khadka. Structures of Mutual Support, 2022. Courtesy of the artists.

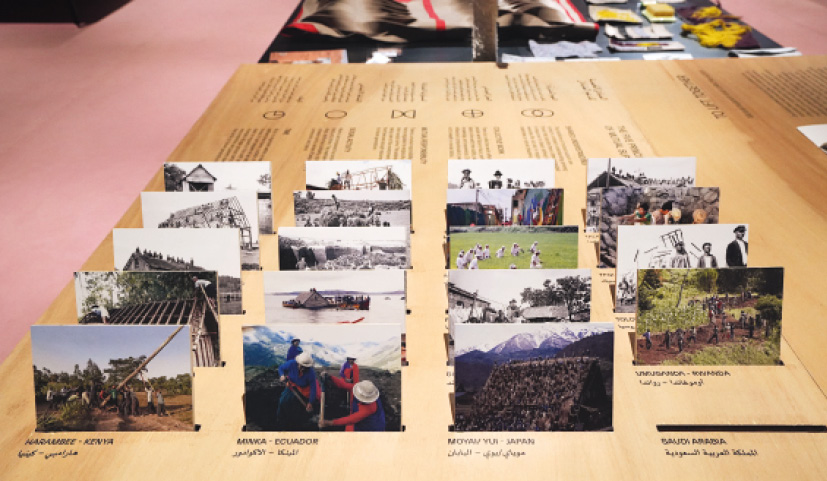

To Lift Together: Mutual Support and Collective Action, research material on display at the research room. Alexander Eriksson Furunes & Sudarshan Khadka. Structures of Mutual Support, 2022. Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, 2024.

Community

The historical shift towards a civilisation of hyper-individuals, who cooperate only when it serves their private interests rather than functioning as a single organism, alludes to how we have all lost touch with one another. Social relationships, from the initiation of casual small talk to formalised occasions, have withered, no longer grounded in connection, but accrued for self-preservation. What, then, is the foundation of a community that can offer a sense of belonging? The communal spirit in this thought path considers communal decision-making and benefits-sharing, through open interaction and transparency, as vital. Individuals can participate and add value to their communities, and to society at large, based on attributes shaped by their knowledge, skills, and experience. Such participation builds towards a degree of cooperativeness and minimises alienation. Members of communities offer “services” to one another, creating a balanced network of interdependence and instituting a more holistic social system. Beyond an individual, can the communal also refer to all life forms? How might we imagine ways of working where all forms of life belong to a diverse commune?

ALEXANDER ERIKSSON FURUNES AND SUDARSHAN KHADKA

Structures of Mutual Support, 2021

An example of architecture as process, the project was initially developed as a collective effort in collaboration with the Gawad Kalinga (GK) Enchanted Farm community in Angat, Bulacan, the Philippines. Rooted in a dialogical approach to community building, it responds to the urgent question “How will we live together?”, a question posed against a backdrop of development models that prioritise market growth and productivity. The project seeks to foster a democratic space where diverse perspectives can be shared and considered collectively, in ways that are socially and environmentally sustainable. It demystifies architectural blueprints, transforming them into participatory exercises through which community members and architects embed shared values and meanings into the built environment. Structures of Mutual Support draws on traditions of communal labour rooted in specific cultural contexts—from the Filipino bayanihan to the Norwegian dugnad, the Vietnamese đôi công, the Brazilian mutirão, and the Arabic majlis. It centres on communal spaces, mutual aid, and the principles of collective construction.

Alexander Eriksson Furunes & Sudarshan Khadka explore the practice of mutual support in different cultures, such as yui in Japan, bayanihan in Philippines and dugnad in Norway. The image shows the maintenance of a thatched roof performed through yui in the village of Shirakawa-go, Japan. Courtesy of the city and the residence of Shiragawa ko.

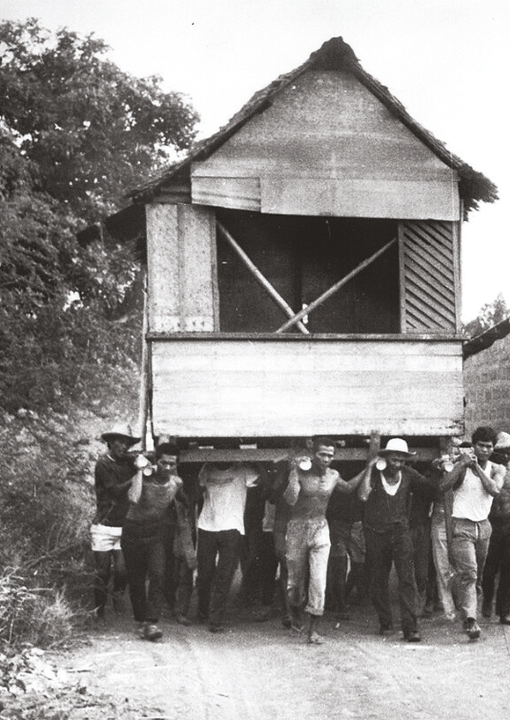

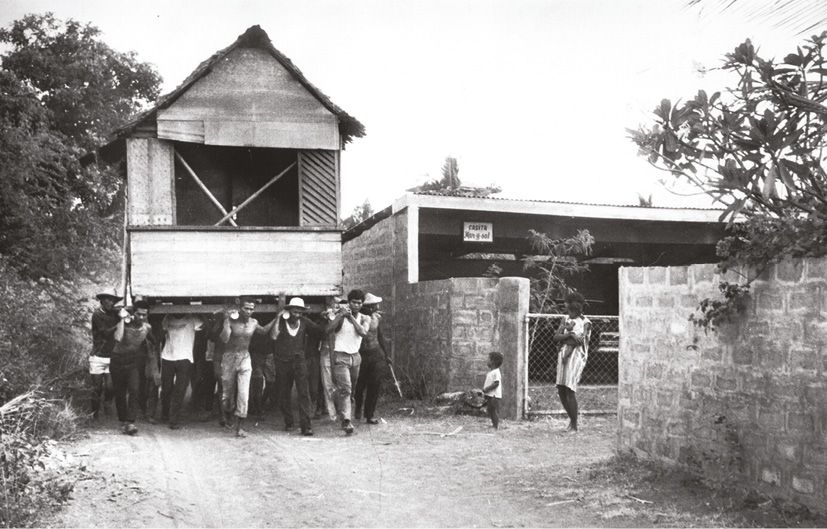

Thirty people moving a house through bayanihan, the Filipino practice of mutual support, civic unity, and cooperation, Nasugbu, Batangas, Philippines, 1972. Alexander Eriksson Furunes & Sudarshan Khadka. Structures of Mutual Support, 2022. Courtesy of Ayala Museum Research Team, Filipinas Heritage Library.

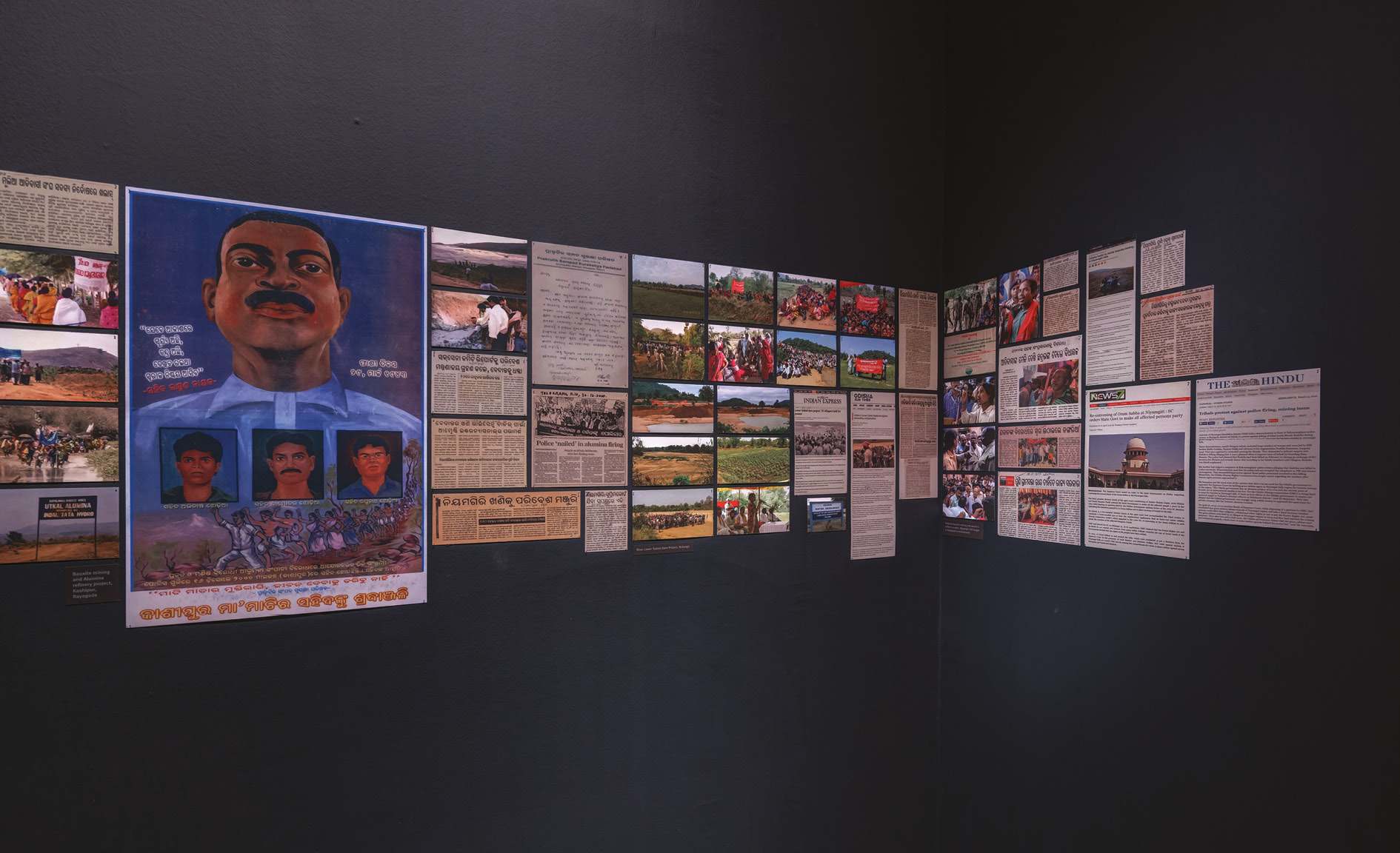

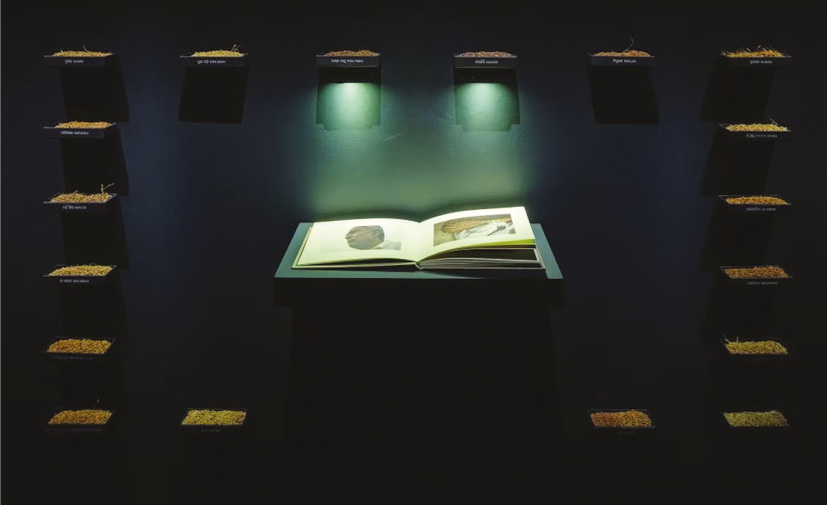

AMAR KANWAR

The Sovereign Forest, 2011–ongoing

The Sovereign Forest attempts to initiate a creative response to the understanding of crime, politics, human rights, and ecology. The validity of poetry as evidence in a trial; the discourse on seeing, compassion, justice, and the determination of the self—all come together in a constellation of films, texts, books, photographs, seeds and processes. The Sovereign Forest has overlapping identities. With each iteration, it reincarnates as an art installation, an exhibition, a library, a memorial, a public trial, an open call for collection of more ‘evidence’, an archive, a school and a proposition for a space that engages with education, politics and art. The work emerges from ongoing efforts in Odisha (formerly Orissa), an epicentre of conflicts between local communities, governments and corporations over control of natural resources such as agricultural lands, forests, rivers and minerals. A series of non-violent resistances by resilient peasants, fisher-folk and tribal communities, powered by autonomous local leaderships, has delayed land acquisitions and influenced the enforcement of new regulations stressing human and community rights.

Part of The Sovereign Forest, a tender love letter about a landscape that once was, now obliterated, and the experience of that loss. Amar Kanwar. A Love Story, 2010, film still. Courtesy of the artist.

Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest: Selections from the Evidence Archive, 2012–2015, 251 digital prints (photographs, documents), contributed, collected, found, installation view at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore. Courtesy of NTU CCA Singapore.

‘Lying Down Protest’ by villagers of Dhinkia, Gadkujang, Govindpur and Nuagaon, Odisha, 11 June 2011. Taken by various photographers. Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest, 2012–ongoing. Courtesy of the artist.

Advocacy

How can we ever stay silent, remaining only as onlookers—from ivory towers to park benches—as though all forms of living species residing, dwelling, and interrelating on landforms and bodies of water are not intertwined? As though spatial happenings from afar, seemingly small and distant, do not ripple in their effects? Advocacy as a form of service can act as an amplifier for unheard stories—those of mountains, oceans, rivers and seas, and other forms of life that speak in languages we consistently fail to listen and acknowledge. It can galvanise support with the intention to effect policy change. By drawing attention to silent witnesses, advocacy can stimulate public awareness, mobilise collective action, and lend weight to movements striving to reshape normative and legal frameworks. It positions care and accountability at the core of governance and environmental stewardship, serving as a stark reminder that the well-being of ecosystems relies on interdependencies between human and nonhuman entities.

272 Varieties of indigenous, organic rice seeds. Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest, 2012, installation view, NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore. Courtesy NTU CCA Singapore.

An experience of a landscape just prior to erasure as territories are marked for acquisition by industries. Amar Kanwar. The Scene of Crime, 2011, film: HD, colour, sound, 42 mins. The Sovereign Forest, 2012, installation view, NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore. Courtesy NTU CCA Singapore.

Conducted by artist Lucy Davis and the ornithologist Abdullah H. Alsuhaibany, the workshop introduced participants to local birdlife and engaged in deep listening exercises. The Migrant Ecologies Projects. If your bait can sing the wild one will come bird-watching workshop, Wadi Hanifah, February 24, 2024, After Rain, Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024.

A banyan recalls a Kelicap Sepah Raja (Crimson Sunbird). Sun-Shadow puppet of found internet bird. Photographed where the bird was last heard, along the rail tracks at Tanglin Halt. The sun-shadowed puppet is part of a stop-motion animation in the Railtrack Songmaps project, developed through a process entitled “Avian Web-Re-Wild”, which involved printing online images and video frames of birds seen or heard in a Nature Society Singapore bird count, commissioned by The Migrant Ecologies Projects, along the rail tracks at Tanglin Halt, Singapore.

The Migrant Ecologies Projects. Railway Songmaps, 2016, stop-motion still of found, internet bird video. Courtesy of Lucy Davis and Kee Ya Ting.

THE MIGRANT ECOLOGIES PROJECTS

{if your bait can sing the wild one will come} Like Shadows Through Leaves, 2021

Founded in 2009 by Lucy Davis as an umbrella for informal, durational, transdisciplinary collaborations in and around art and ecology, primarily in Southeast Asia. It involves the communities along the railway, involving other art practitioners. One of these formats is the above-mentioned film, that unfolds the artists’ long-term engagement with Tanglin Halt, one of Singapore’s oldest public housing estates, which runs alongside a former railway track. The land, once an indeterminate-governance zone, played host to a fecund variety of more-than-human activities—105 species of birds were observed by ornithologists in this plot of land. Once a gathering place and home to community farms and unofficial tree shrines, it has since been repurposed as a green corridor park. Repeated returns to the site trace lingering remnants of calls, echoes, shadow memories, and transformative encounters that continue to animate this zone.

Other formats are workshops such as a bird-watching workshop at Wadi Hanifa on the outskirts of Riyadh conducted by Davis and ornithologist Abdullah H. Alsuhaibany, introducing participants to local birdlife and engaging them in deep listening exercises, on the occasion of the 2024 Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale.

Zachary Chan and Lucy Davis, Songmap for Lim Kim Seng and Lim Kim Chua, 2020, from Railtrack Songmaps, 2015–ongoing. The Migrant Ecologies Projects, Railtrack Songmaps Roosting Post 2 (2020), Jendela, The Esplanade, Singapore.

URSULA BIEMANN

Devenir Universidad, 2019–2022

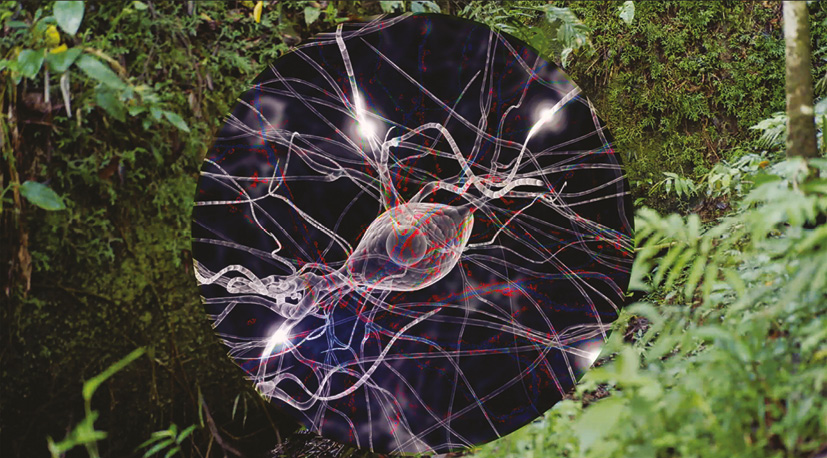

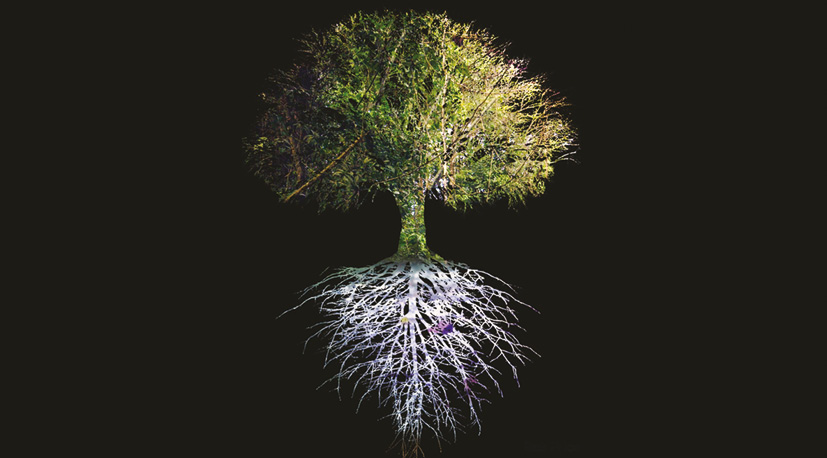

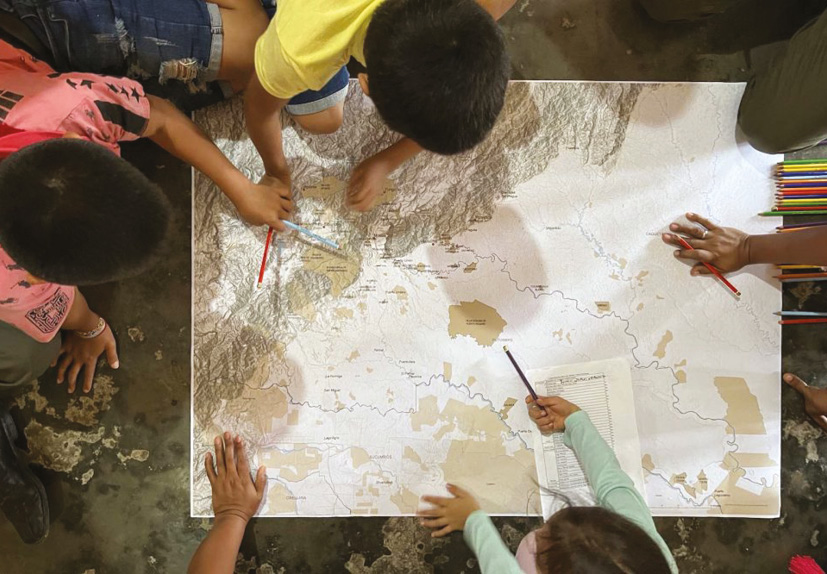

At the invitation of the leader of the Indigenous Inga people, Hernando Chindoy, and with the support of academic and non-academic partners, an Indigenous University was co-created to transmit ancestral knowledge of the living, sentient Andean Amazon forest and help reconnect dispersed community through the establishment of an intellectual center, one that is not centralised but spreads across the entire territory in a network of learning paths. Decades of armed conflict and a history of colonial occupation have dismantled the structures necessary to foster epistemic cultures. The co-creation of an indigenous university is intended to formulate a collaborative network of different human and other-than-human thinking and acting together with the territory. At its core lies the biocultural paradigm, which recognises that biological, cultural and epistemic diversity have co-evolved and are inseparable from one another.

These images are reproduced from Devenir Universidad www.deveniruniversidad.org,2021

Ursula Biemann. Forest Mind, 2021, video still.

Ursula Biemann. Field research at the South of Colombia, 2018, Devenir Universidad. Courtesy of the artist.

Guardianship

In recent news, crows and other bird species attacking drones in various parts of the world have become common sights and reports. These birds are not necessarily territorial but are protective of their environment against objects perceived as threats. In various Southeast Asian mythologies, birds symbolise spiritual guardianship, strength, and protection. The network of knowledge exchange between human and more-than-human thinking can be manifested through keen observation and attunement to one’s place and surroundings, by virtue of coexistence and a sense of responsibility. In this vein, Indigenous communities understand their relationship with the environment not as service, but as stewardship. Learning from the Pacific islands, they see themselves as guardians of land and sea—a continuum rather than a division. In Papua New Guinea, rather than land ownership, people consider themselves custodians of the land. The extends to a cooperation with multispecies custodians, who allow them to speak on behalf of their habitats, which comprise complex ecosystem of living entities, each possessing intrinsic rights and spiritual representation.

Ursula Biemann. Forest Mind, 2021, video stills.

4K UHD video, sound, 31:45mins. Courtesy of the artist.

First round of meetings in five zones of Inga territory to collectively draw biocultural cartographic representations in support of intercultural higher education, between 28 June to 12 July, 2022. Ursula Biemann. Devenir Universidad, 2019–2022. Photo by Álvaro Hernández Bello. Courtesy of the artist.

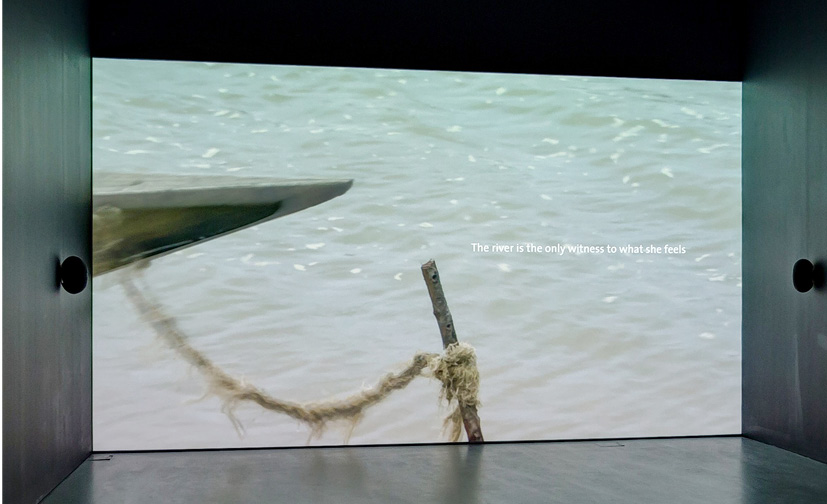

MARTHA ATIENZA

Adlaw sa mga Mananagat / Fisherfolk Day, 2022

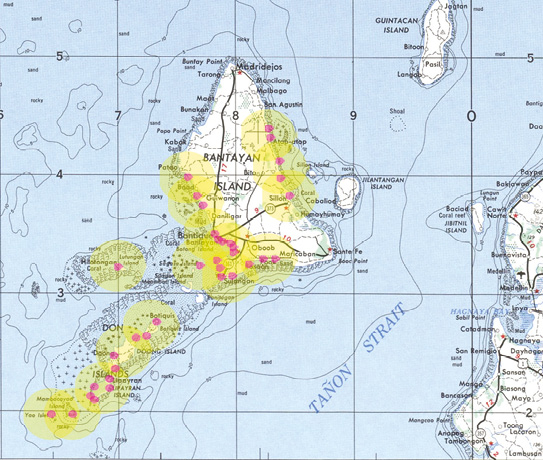

In the Visayas region of the central Philippines, the fishing communities of Bantayan Islands have for decades borne the brunt of the adverse impacts of commercial ventures backed by the government. Framed as a pathway to development and economic growth, the islands of Bantayan have witnessed increased dispossession of over 9,000 fisherfolk in one of the many islets through land privatisation and the creation of an economic zone allowing foreign nationals to fully own assets. Tourism was promoted as alternative livelih ood, effectively forcing fisherfolk into labourers working for resort owners. GOODLand emerged out of this process as a platform for Local Government Units (LGUs), NGOs and small-scale fisherfolk to work collaboratively on the preservation, protection and the eventual alteration in marine food resources, working with existing local and national fishery policies. As a result of this initiative, the Resolution No. 27, which established a Marine Protected Area (MPA) in Mambacayao Dako, and an ordinance declaring a yearly Bantayan Fisherfolks’ Day/ Adlaw sa Mga Mananagat were passed. Adlaw sa mga Mananagat comprises three video works that came forth out of the last three to five years that Martha Atienza has, collaboratively, been working to ensure that Bantayanons have a say in the future of their islands.

Location of 37 coastal communities: 11°14’46.4”N 123°44’08.7”E, Municipality of Bantayan, Central Visayas, Tañon Strait, Visayan Sea, Cebu, The Philippines.

Martha Atienza, Adlaw sa mga Mananagat (Fisherfolks Day), 2022. Courtesy of the artist and GoodLAND derneği.

Martha Atienza. Adlaw sa mga Mananagat (Fisherfolks Day), 2022. Courtesy of the artist and GoodLAND derneği.

Martha Atienza. Drone shot of a boat parade in the waters around Bantanyan Island in celebration of Fisherfolks Day, 2022.

Martha Atienza. Ordinance declaring 31st May of every year as “Bantayan Fisherfolks’ Day”.

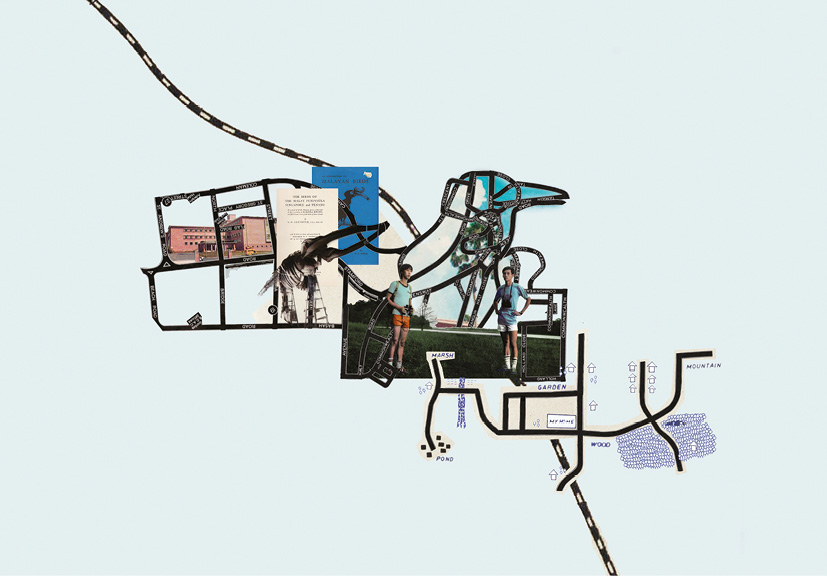

YEE I-LANN

TIKAR/MEJA, 2020–ongoing

TIKAR/MEJA is a series of mats developed by Yee I-Lann and indigenous weavers from the Bajau Sama DiLaut communities in Sabah, Malaysia. The meja (table), according to Yee, represents “the violence of administration” in colonial and patriarchal societies. The tikar (woven mat) in contrast is fundamentally egalitarian, grounding one to the earth. Since pre-colonial times, the tikar has been a common object for socialisation, community, and relaxation across Southeast Asia. In juxtaposing these forms, by bringing the table and mat together, Yee posits: “A table on a mat is like a stone on paper in a game of rock-paper-scissors, where my open hand encloses your fists. To decolonise is to see the table and to see the mat.”

A social dimension is further layered in Yee’s artistic practice. These assemblages of mats through collaborative weaving have generated economic opportunities for communities involved, while simultaneously raising awareness of the importance of preserving indigenous cultures and traditions. They build towards the collective desire to foster social and ecological resilience in response to the devastating effects of sea and land use and climate change.

TIKAR/MEJA/PLASTIK is woven by Aisyah Binti Ebrahim, Alini Binti Aniratih, Alisyah Binti Ebrahim, Ardih Binti Belasani, Darwisa Binti Omar, Dayang Binti Tularan, Dela Binti Aniratih, Endik Binti Arpid, Erna Binti Tekki, Fazlan Bin Tularan, Kinnuhong Gundasali, Kuoh Binti Enjahali, Luisa Binti Ebrahim, Makcik Lukkop Belatan, Makcik Siti Aturdaya, Malaya Binti Anggah, Ninna Binti Mursid, Noraidah Jabarah (Kak Budi), Roziah Binti Jalalid, Sabiyana Binti Belasani, Sanah Belasani, Tasya Binti Tularan, and Venice Foo Chau Xhien.

Yee I-Lann. TIKAR/MEJA/PLASTIK, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

Yee I-Lann. Tikar Meja, with weaver Adik Umairah (Left) and Adik Marsha (Right), 2023.

Photo by Chris Perreira. Image courtesy of the artist and Silverlens.

Ownership

What does ownership look like in the context of the global commons? Who gets to claim the vast oceans and what lies beneath? What responsibilities and ethical concerns arise when asserting ownership over a resource? Can a single entity own a cultural heritage, a shapeshifter that adapts and transforms across time and context, and what might equitable intellectual property rights look like when that heritage is shared among many? Yet, where institutions are faced with complex questions and challenges, and when they are overstretched, inaccessible, or indifferent, instead of passively waiting for a service to be provided or support to be rendered, artists and their communities often take steady steps towards owning a problem, challenge, or situation, establishing their own form of service that becomes crucial steps towards building sustainable modes of livelihood and ways of living together. Such initiatives should not be perceived as merely individual acts of self-reliance, but as gestures that reframe agency and responsibility within a broader social ecology. Here, shared culture is celebrated, not divisive.

TIKAR REBEN, 2020

The motifs within Tikar Reben bear an index of multilingual and multigenerational heritage patterns that communicate weaving techniques and knowledge. Tikar Reben—in its accompanying video—documents the unrolling of the 53-metre tikar across the divide between the Malaysian Omadal Island village and the stateless Bajau Sama DiLaut weavers’ water village. The weaving and the woven mat become a cultural bridge, celebrating a shared cultural identity across a geopolitical landscape marked by prejudice.

A 53-metre-long ribbon containing an index of foundational counting patterns that make up Bajau Sama Dilaut woven patterns and motifs. Yee I-Lann. Tikar Reben, 2020. Photo by Andy Chia. Courtesy of the artist and Silverlens.

Accountability

Environmental justice is social justice. It is multispecies justice. It is political justice. It is migrant justice. No longer are we disjointing various forms of aggression, oppression, terrorisation as separate and distinctive from one another. The various forms of service in the supply chain industry—encompassing the destruction of natural landscapes for raw materials, the atrocious wages and forced labour from developing nations leveraged to meet demand and ensure efficiency for the global supply of endless goods—are often carried out under the guise of environmentalism: a practice termed as greenwashing, a misleading green sheen that does more harm than good. A service to the environment necessitates greater transparency and accountability, as it otherwise risks becoming a form of eco-colonialism or neo-colonialism, marked by human rights and environmental violations.

NABIL AHMED/INTERPRT

Mining the Abyss, 2022

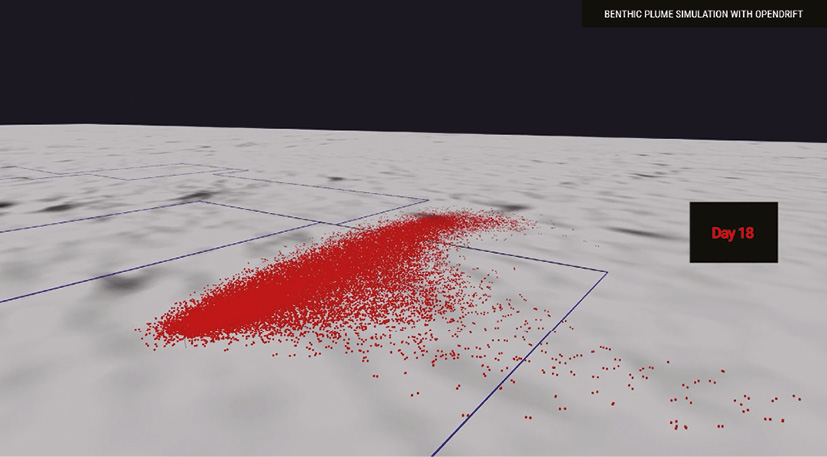

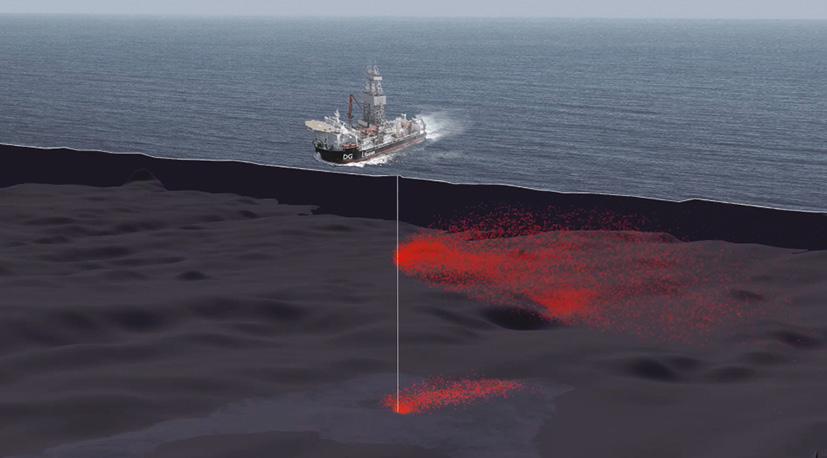

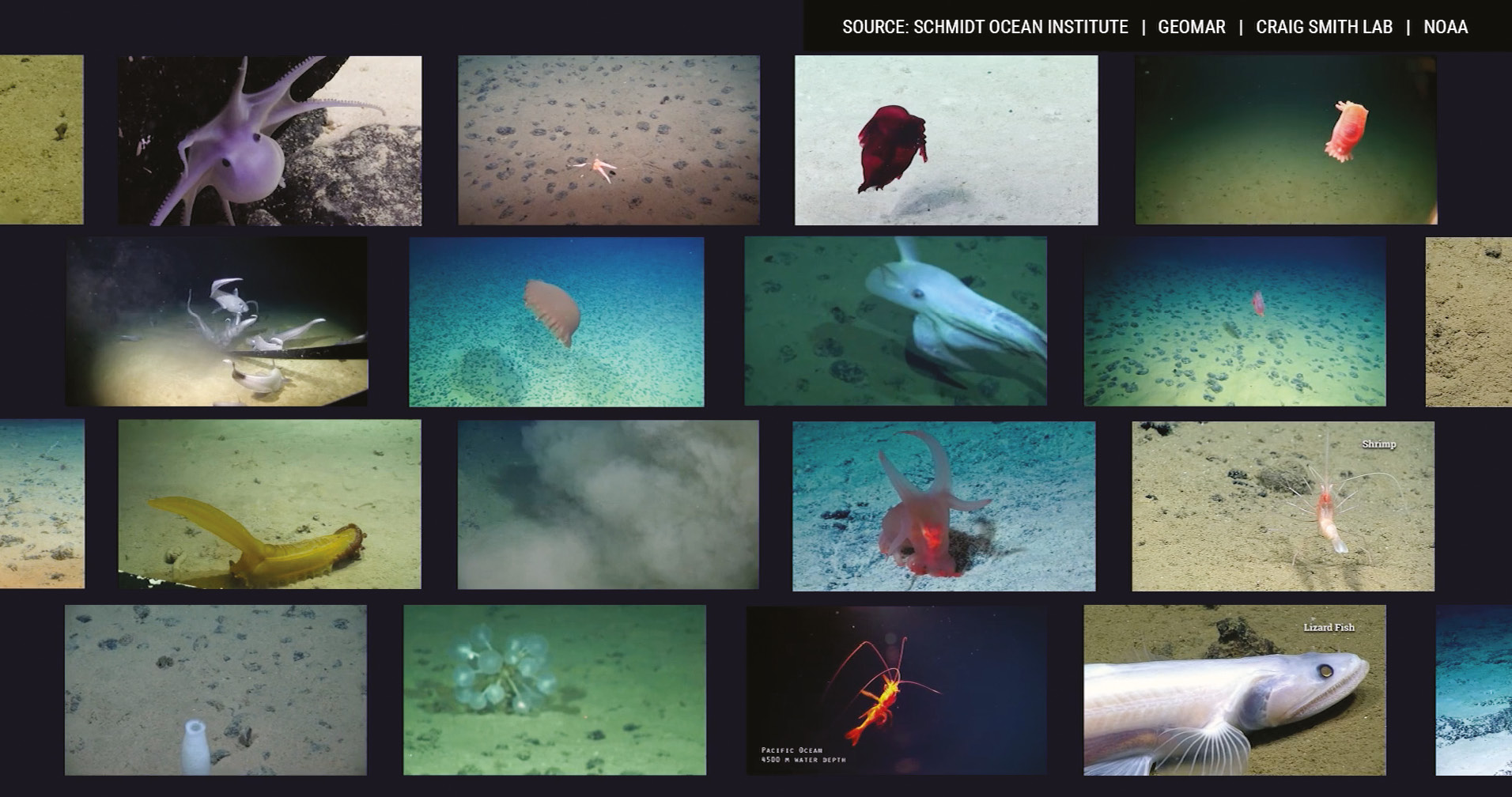

Challenges in the spatial and visual representation of the vast and deep ocean have proven advantageous for the mining industry, which often claims excavation operations to be environmentally friendly. To counter greenwashing tactics, INTERPRT analysed data shared by marine biologists to simulate mining footprints and collaborated with an oceanographer to model the trajectory of plume particles from seabed mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Blue Peril, a multimedia advocacy tool created using 3D modelling software, visualises for the first time the vast area of the Pacific expected to be impacted by deep-sea mining and the potential devastation it could bring to marine ecosystems and habitats. Mining the Abyss is a visual investigation on deep-sea mining and accountability.

INTERPRT. A visual investigation on deep-sea mining and accountability in the Pacific Ocean. A visual demonstration of plume distribution in the Nori D contact area using Open Drift.

A visual investigation on deep-sea mining and accountability in the Pacific Ocean. Vertical settlement particles of plumes during the processing of mineral nodules on surface ships. INTERPRT. Blue Peril, Mining the Abyss, 2022, film stills. Courtesy of INTERPRT.

INTERPRT. A visual investigation on deep-sea mining and accountability in the Pacific Ocean. The diverse and rich deep-sea ecosystem in the Clarion-Clipperton zone.

ARMIN LINKE

Prospecting Ocean, 2018

In Prospecting Ocean, Linke scrutinises the administration of the oceans and exposes the simultaneous fascination with and alienation from modern technologies that map, visualise, and exploit resources in the ocean. Prospecting Ocean, the title film which lends the exhibition its name, is a cinematic journey that traverses gatherings of decision-makers often off-limits to the public, from the United Nations assemblies, international law conferences, marine research centers, deep-sea mining companies and activist meetings. Through a series of photographs, critical texts and key documents, and filmed interviews with marine biologists, geologists, policymakers, legal experts, and activists, Linke grapples with the tensions between ecological protection and exploitation of the ocean, a global common. The material is an invitation to consider the implications of oceanic excavations and resource extraction for both the environment and local economies and cultures.

Armin Linke. Twenty-Second Session of the International Seabed Authority Assembly, ISA, Kingston, Jamaica, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Armin Linke. OCEANS. Dialogues between ocean floor and water column, 2017, video still.

Installation view: OCEANS. Dialogues between ocean floor and water column, Edith-Russ-Haus for Media Art, Oldenburg, 2017. Courtesy of Armin Linke and ROV Video Archive Material GEOMAR - Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel and MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen. The project was commissioned and co-produced by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Academy (TBA21), Vienna.

Armin Linke. OCEANS. Dialogues between ocean floor and water column, 2017, The Oceanic (2017–18), installation view at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore. Courtesy of NTU CCA Singapore.

Exchange

The invention of paper money finds its history resting on the bark of the mulberry tree—a tree native to Asia and North America, and prevalent in China for the cultivation of fruit and sericulture. The white bast of the tree, resembling sheets of paper, was issued as a form of authorisation and formal transaction. Yet a single sheet of paper holds no greater meaning or value than the tree itself, the tree that provides sustenance and shade. Interactions from transactions have now been reduced to the mere fufillment of agreed terms in exchange for payments. The characteristic of service provision in today’s impersonal market economy implies a contractual obligation shaped by monetary value. This trickles down to educational institutions as well. In response to this, various artists’ projects, including the Silent University, point to a return to reciprocal exchange rooted in sustained relationships and shared responsibilities. Knowledge and skills are not commodified; rather, they are contributions that feed into education for all. In doing so, these initiatives foster a more equitable and relational form of association, where value is not measured solely by economic terms but by the quality of interaction, mutual recognition, and the ongoing maintenance of community bonds.

AHMET ÖĞÜT

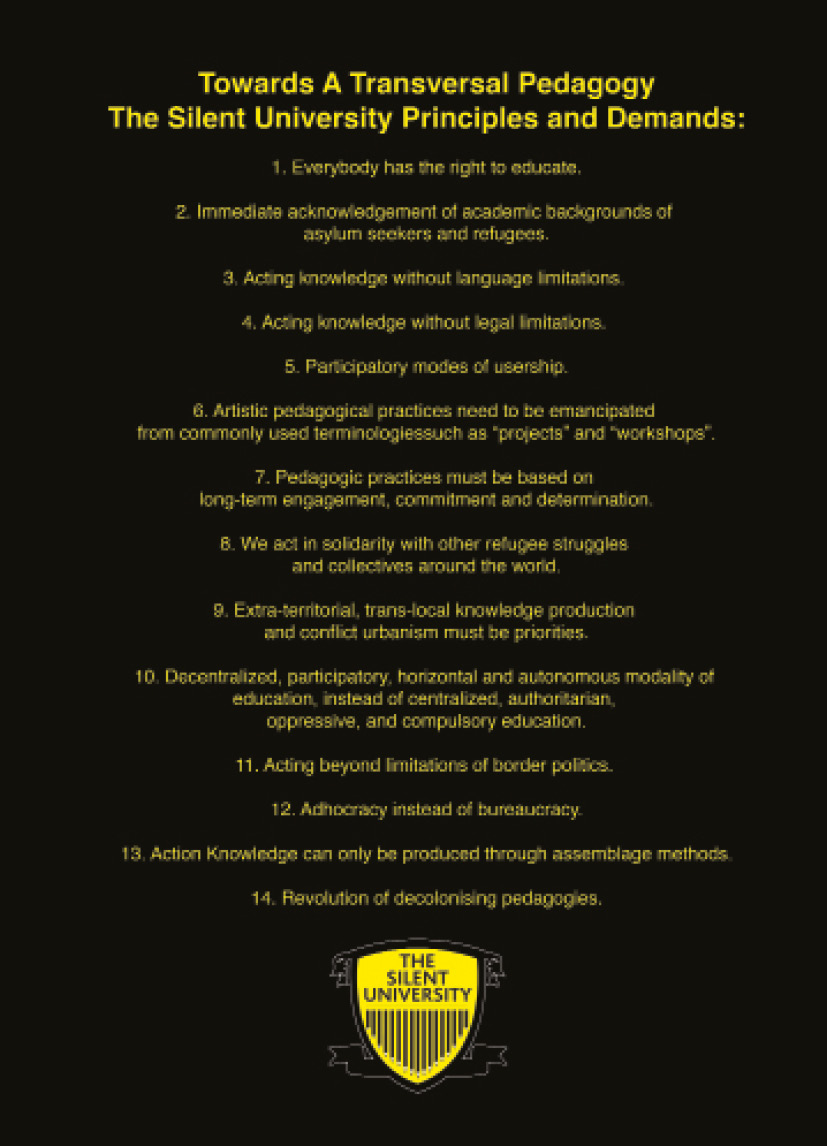

Silent University, 2012–ongoing

A solidarity-based knowledge exchange platform by and for displaced people and forced migrants, it operates outside the restriction of migration laws, language limitations and other bureaucratic hurdles. Founded in 2012, it has multiplied itself on smaller scales in different cities, establishing active branches in Sweden, Germany and more recently, Turkey. The impetus of the establishment is rooted in the belief that everybody has the right to educate, and that systemic failure is not an excuse to outlaw those who are seeking asylum. In Öğüt’s words, the objective is to sustain long-term peer-to-peer recognition and care. With ideological and practical principles firmly rooted, the Silent University remains even as directors of collaborating institutions change over the years.

Ahmet Öğüt and The Silent University Team. The Silent University, 17 September–20 November 2022, 17th Istanbul Biennial, installation view at the Museum Hasanpasa Gashouse. Photo by Sahir Ugur Eren. Courtesy of Istanbul Biennial.

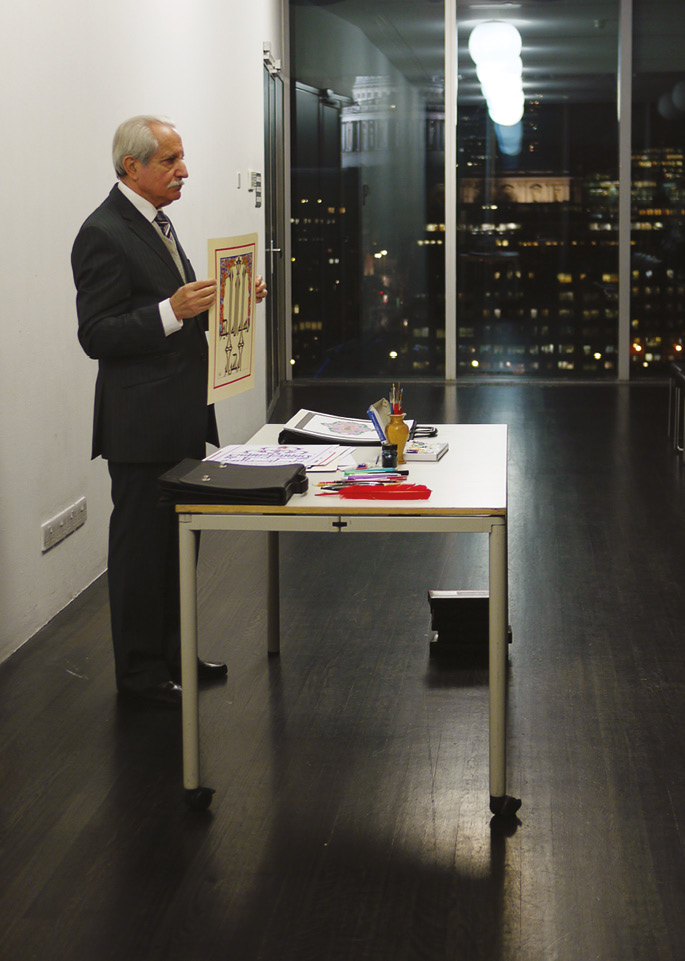

A Silent University discussion at Tate Modern. Ahmet Oğüt and The Silent University Team.

The Silent University, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and The Silent University.

Presentation on Arabic calligraphy by calligrapher Behnam Al-Agzeer at Tate Modern. Ahmet Oğüt and The Silent University Team. The Silent University, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and The Silent University.

The Silent University. Towards a Transversal Pedagogy: The Silent University Principles and Demands, 2012. Courtesy of the artist and The Silent University.

TEXT CREDITS

Additional texts are authored by Anca Rujoiu (Britto Arts Trust and Migrant Ecologies Project), and Alexander Eriksson Furunes and Sudar Khadka (Structures of Mutual Support).

Artists’ biographies are authored by Laura Schleussner (Armin Linke, Ursula Biemann, Migrant Ecologies Project, and Alexander Eriksson Furunes and Sudarshan Khadka).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to Milenko Prvački and to editor Venka Purushothaman, who extended the invitation for us to curate this chapter on this year’s theme of Service for the ISSUE Art Journal. Our thanks also go to the editors Susie Wong and Weixin Quek Chong, as well as to graphic design firm Sarah and Schooling, for their care and patience throughout this process. We are indebted to the artists featured in this section for allowing us to use their material, and the authors who have contributed to the various artwork texts.

We would also like to thank the 17th Istanbul Biennial, the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, and TBA–21 Academy The Current, where these artistic projects were presented.

ARTISTS’ BIOGRAPHIES

Nabil Ahmed/INTERPRT (b. 1978, Dhaka, Bangladesh) has been researching environmental conflicts for over fifteen years. His spatial practice and writing interrogate the representational challenges of environmental destruction and conflict across visual culture and law. He is Professor of Visual Intervention at the Trondheim Academy of Fine Art (KiT) in the faculty of architecture and design at Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and the founder and co-director of INTERPRT, a research agency that pursues environmental justice through spatial and visual investigations. He holds a PhD in Research Architecture from the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London where he was one of the founding members of Forensic Architecture. He sits on the advisory board of Stop Ecocide International.

Martha Atienza (b. 1981, Manila, Philippines) is a Dutch-Filipino video artist exploring the format’s ability to document and question issues related to the environment, community, and development. Her video works are rooted in both ecological and sociological concerns as she studies the intricate interplay between local traditions, human subjectivity, and the natural world. Atienza’s artistic practice navigates a time and space of her family of seafarers where both lands and seas from where they come carry a story of historical migration, cultural identity, and now, current social and political state of affairs in the Philippines. Atienza was awarded the Baloize Art Prize in Art Basel for her seminal work Our Islands in 2017. Recent biennales and triennials include the 17th Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul (2022), Bangkok Art Biennale: Escape Routes, BACC, Bangkok (2020), Honolulu Biennial: To Make Wrong / Right / Now, Oahu, Hawaii (2019); and the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, QAGOMA, Brisbane (2018). Her solo exhibition The Protectors inaugurated Silverlens New York in 2022.

Ursula Biemann (b. 1955, Zurich, Switzerland) is an artist, video essayist, and writer. Her research-oriented practice is based on extensive fieldwork in remote landscapes, where she investigates the geopolitics of climate change and the human impact on natural ecologies, questioning the role of modern science in decolonial knowledge production. Biemann’s artistic training began in Mexico City. She then studied at New York’s School of Visual Arts and later at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s prestigious Independent Study Program. She was awarded the Swiss Grand Award for Art / Prix Meret Oppenheim in 2009. Biemann has an honorary doctorate in humanities from the Swedish University in Umeå. Biemann’s intellectual and incisive video essays intricately interweave cinematic vistas with documentary footage, science fiction speculations, and academic scholarship, forming a web of knowledge in which boundaries of epistemological realities are tested, stretched, and expanded.

Britto Arts Trust (Dhaka, Bangladesh) is an artist-run non-profit collective founded in 2002. Based in Dhaka but working extensively in different locations across the country, the collective attempts to understand Bangladesh’s socio-political upheaval by exploring missing histories, cultures, and communities and collaborating with various partners. Britto seeds and promotes multiple interdisciplinary practitioners, groups, and networks. It provides an international and local forum for the development of professional art practitioners, a place where they can meet, discuss, experiment, and upgrade their abilities on their own terms. In response to the lack of suitable educational institutions in Bangladesh, Britto functions as an alternative learning platform for many artists who have gone on to produce highly experimental work. Britto is a lumbung member of documenta fifteen, where as part of their participation they created a vivid interconnected landscape devoted to food politics, displacement, and culture.

Alexander Eriksson Furunes (b. 1988, Trondheim, Norway) and Sudarshan Khadka (b. 1986, Manila, Philippines) have been working together since 2014, when the two first collaborated on Streetlight Tagpuro, a post-disaster rebuilding project in the City of Tacloban, Philippines, after super-typhoon Haiyan. The project won awards in the Civic and Community and Small Project of the Year categories at the World Architecture Festival in 2017. Aligned through a deep commitment to the concept of mutual support, Furunes and Khadka have realised multiple projects since. Founded on participatory planning and construction, often in rural contexts, the communal structures that they facilitate are enabled by the traditions of communal work specific to each respective cultural context. The pair, in collaboration with the Gawad Kalinga (GK) Enchanted Farm community in Angat, Bulacan, Philippines, were invited to curate the Philippine pavilion of the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale (2021), presenting Structures of Mutual Support as an example of architecture as process.

Amar Kanwar (b. 1964, New Delhi, India) has distinguished himself through film and multi-media works, which explore the politics of power, violence and justice. His multi-layered installations originate in narratives often drawn from zones of conflict and are characterised by a unique poetic approach to the personal, social and political. Interweaving narration, image and sound, Kanwar’s distinct filmic flair foregrounds layered documentation, rather than exposing the absurd, yet historically solidified scars and rituals of separation as well as the violence, hopes and dreams of the people affected in a one-dimensional manner. Kanwar has participated in Sharjah Biennial 10 and 11 (2011, 2013) and documenta 11,12, 13 and 14 in Kassel, Germany (2002, 2007, 2012, 2017), the Kochi-Muziris Biennial, India (2022) and Sharjah Biennial, United Arab Emirates (2023). Recent solo exhibitions of Kanwar’s work have been held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2022); Ishara Art Foundation, Dubai, UAE and NYU Abu Dhabi Art Gallery, UAE (2020), Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid (2019), Tate Modern, London, among others. He was a co-curator for the 17th Istanbul Biennial (2021).

Armin Linke (b. 1966, Milan, Italy) is a photographer and filmmaker who documents the impact of globalisation, the built environment, and post-industrial economies while questioning the nature of the nature of the photographic medium, its technologies, narrative structures, and complicities within wider socio-political structures. In a collective approach with creatives, researchers and scientists, Linke has explored topics ranging from space mining to a particle physics laboratory, power sources, and his own photographic archive. He has had solo exhibitions at Centre Pompidou (2023/2024), the Canadian Centre for Architecture (2023), and the Luxembourg Pavilion at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale (2023). He is a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts Munich.

Migrant Ecologies Projects was founded in 2009 by visual artist, art writer, and academic Lucy Davis (b. 1970, United Kingdom) as an umbrella for for collaborative, transdisciplinary inquiries into questions of art, ecology and more than human connections, primarily but not exclusively in Southeast Asia. Davis’ transdisciplinary practice encircles plant genetics, tree lore and bird song as well as art/science, naturecultures, memory, materiality, narrative environments, and most recently, psycho-ecologies of resilience. Davis was a founding member of the School of Art, Design and Media, Nanyang Technological University Singapore. She is currently Associate Professor (Contemporary Art) and Head of the MA in Visual Cultures, Curating and Contemporary Art (ViCCA), Department of Art and Media, Aalto University, Finland. Her collaborators on the Migrant Ecologies Projects are artists Zachary Chan, Kee Ya Ting, and Zai Tang with fields of practice in sonic arts and graphic design, photography and video production, and sound design, respectively.

Ahmet Öğüt (b. 1981, Amsterdam, Netherlands) is a Kurdish artist, sociocultural initiator and lecturer. Öğüt works across a variety of media, including photography to drawings, video and installation to interventions and performance, examining everyday modes of behaviour, employing humour and small gestures to respond to urgent social and political issues. He meanders, blurring the lines of artistic practice and social life to provoke critical consciousness and shift in perspective. He initiated the Silent University in 2012 during a residency at Tate Modern, as an international knowledge platform by and for refugees, asylum seekers and migrants. Öğüt has exhibited widely, more recently with solo presentations at Kunstverein Dresden, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Chisenhale Gallery, and Van Abbemuseum.

Yee I-Lann (b. 1971, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia) is a leading contemporary artist recognised for her predominantly photography-based practice. Her digital photo collages delve into the evolving intersection of power, colonialism, and neo-colonialism in Southeast Asia, shedding light on the influence of historical memory in social experiences. Often centering on counter-narratives or “histories from below”, she has recently begun collaborative work with sea-based and land-based communities, as well as indigenous mediums in Sabah, Malaysia. Yee has exhibited widely in Museums across Asia, Europe, Australia, and the United States, notably The Spirits of Maritime Crossing, Venice, Italy (2024); NGV Triennial, Victoria, Australia (2023); Soft and Weak Like Water: The 14th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, South Korea (2023); the 17th Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul, Turkey (2022).

References

1 Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, et al. Phenomenology of Spirit. Reprint., Oxford Univ. Press, 2013.

2 Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. Reprint., Lawrence & Wishart, 2012.

3 Wendt, Wolf Rainer. Ecology of Common Care: The Ecosocial Approach As a Theory of Social Work and Human Service. Springer International Publishing AG, 2021.

4 Saunders-Hastings, Emma. ‘Benevolent Giving and the Problem of Paternalism’. Effective Altruism, edited by Hilary Greaves and Theron Pummer, 1st ed., Oxford University Press Oxford, 2019, pp. 115–36. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198841364.003.0008.

5 Groys, Boris. Philosophy of Care. Verso, 2022.

6 Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. 1st ed., Prickly Paradigm Press, LLC, 2003.

7 Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. New paperback printing, Princeton University Press, 2021.

8 Maria Puig de La Bellacasa, María. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. University of Minnesota press, 2017.

Essays

Divine Inspiration: The Art of Service

Philosophically considered, service is not a derivative act of compliance but a primordial modality of relational being—a movement that mediates between the unmanifest and the manifest, the Absolute and the contingent. It is a teleological arc, a vector of intentionality that does not originate in the ego but traverses it, directing it toward something beyond itself.

Within this ontological framework, in art, servant leadership may be conceived as the animating principle—the nous or motor—behind acts of genuine creation and inspiration. Just as the artist becomes a vessel for the arrival of form from the formless, so too does the servant-leader operate not through assertion of will, but through attunement to what demands to be realised. In this respect, the servant is not the antithesis of power but its reconfiguration: it is power rendered transparent to the source it serves.

Artistic inspiration, however, often mythologised as divine madness or genius, may thus be understood as the epiphenomenon of a deeper submission—a creative servitude in which the leader does not dominate the vision, but midwifes it. Rumi’s evocative formulation, I am the servant of the servant of those who serve the Truth, unfolds within this metaphysical hierarchy, revealing that the truest authority arises not from mastery, but from the willingness to be moved by that which transcends mastery. This essay explores the metaphysics of service as a structure of mediation and emergence, situating servant leadership as the epistemic and spiritual infrastructure underlying both ethical action and creative expression.

Throughout history, the concept of service has quietly shaped the ways in which artistic creation has been understood and practised across cultures. In many traditions, the artist was not seen as a sovereign creator but as a mediator—one who receives and transmits rather than originates. In ancient Greece, the poietes functioned as a vessel for the muse, with inspiration understood not as internal genius but as a form of possession, an act of alignment with the divine. Likewise, medieval Christian art was embedded in a theological framework where the artist operated as a servant of the Logos, producing visual and material forms as offerings rather than expressions of individual will. Islamic aesthetics, particularly through its iconoclastic disciplines, redirected artistic energy into geometric and calligraphic modes—forms of devotional precision that reflect a deeper metaphysical structure of submission and repetition. In East Asian contexts, particularly Zen-inflected Japanese art, the act of creation is intimately tied to ego-effacement and attunement to the Dao, reinforcing the idea that artistry arises from disciplined emptiness rather than expressive force. What emerges across these diverse settings is a shared ontological logic: that art, at its most profound, is not the assertion of the self but the enactment of service—service to the sacred, to tradition, to form itself. In this sense, service is not ancillary to aesthetics but foundational to it: the silent architecture beneath inspiration, where the artist becomes not master, but intermediary.

“I asked God for a download...”

Often serving as the principal impetus for creation, religion held a fundamentally constitutive role in the formation, function, and symbolic language of ancient art, shaping both its content and its cultural context. In this framework, art itself operated as a medium of service—a devotional offering, a visual theology, and a ritual instrument through which the divine was invoked, honoured, and made present. Akin to a servant, the artist became a conduit rather than an originator, channeling collective belief into material form, serving the metaphysical order and sustaining the continuity between the earthly and the sacred. Artistic works were frequently commissioned by religious entities or political elites to fulfil sacred functions, adorning temples, tombs, and sanctuaries in order to mediate between the divine and the human. The service was visible through the iconography of deities, divine mythologies, and sacred rituals that were not merely ornamental, but imbued with profound theological significance, facilitating both the communication of religious ideologies and the reinforcement of cosmological order.

Furthermore, religious art played a crucial role in legitimising political authority by associating rulers with divine will, thereby consolidating both temporal power and spiritual dominion. In this sense, religion was not just a thematic presence over the history of art, but a structural force that dictated the very framework within which artistic expression occurred, acting as the primary means by which societies negotiated their understanding of the sacred, the political, and the social.

In both the ancient and medieval epochs, the role of the artist within the realm of devotional art was that of a servant, inextricably bound to religious and institutional imperatives, where the artist’s service transcended individual autonomy, positioning them as a conduit for divine inspiration and a subordinate executor of sacred mandates.

In these contexts, the artist was regarded not as an autonomous creator, but as a skilled artisan or spiritual servant whose work was dictated by theological, liturgical, and political decrees, often under the auspices of various confessions, temporal rulers, or the Church. The creation of devotional art was conceived as an act of piety, wherein the artist’s labour was not a mere personal or aesthetic undertaking, but rather a ritualised process aimed at embodying divine principles within tangible visual forms. In the ancient world, artists operated within the confines of temples or royal courts, producing works that served to venerate deities and immortalise sovereign power. As Saint Irenaeus claimed (IV, 20, 7), the Son, the divine Word, preserved “the invisibility of the Father”, therefore Christianity in art manifests the invisible. This manifestation can take the most diverse forms, because what we perceive is not ‘phenomena’ (phainómena, visible things); instead, everything has been formed by the Word of God (Hebrews 11, 3: in the Vulgate, the worldly things (saecula) were formed ut ex invisibilibus visibilia fierent).

Equally central to the artist’s role was the notion of divine inspiration, which, according to the Western medieval theological understanding, imbued the artist with the visionary capacity to manifest sacred truths. This inspiration was conceived not merely as a psychological or intellectual process, but as a form of spiritual illumination bestowed through prayer, contemplation, or divine grace, which informed and directed the artist’s vision and execution. The artist’s service, therefore, was regarded not as a secular skill but as a sacred vocation, wherein the creative process was seen as a channel through which the divine revealed itself to the material world. The artistic result, consequently, was not reducible to a mere confluence of technique and intention; it was an articulation of transcendent realities, a manifestation of divine truths realised through the artist’s handling of a certain language. In both the ancient and medieval periods, then, the artist’s role was profoundly multifaceted—acting as both a servant of religious vision and a vessel through which divine inspiration was realised in the tangible world, establishing an enduring link between the sacred and the visual.

Moving the exploration of artistic service towards the East, in the inaugural verse of the Quranic revelation, the verb “read” is the fundamental marker in the Islamic ontological lexicon. Thus, calligraphy is perceived as being a transcription of the Word of God and the first calligraphers were actually the Prophet’s companions who were transcribing verses on various rudimentary supports.

In Chinese cosmology, li (礼)is conceptualised as a ritualistic praxis, the service through which human agency engages with and participates in the grand cosmic order. The term rite is often interpreted as a performative act of service that brings the invisible, metaphysical structures of the universe into the visible realm of human experience, thereby manifesting the underlying cosmic order. When enacted with precision, li serves as a mechanism that organises and coordinates the social world in accordance with the celestial and terrestrial realms, ensuring the preservation of harmony across these interconnected spheres.

Throughout Asia, li was perceived not merely as a formal system of rituals, but as an abstract metaphysical force integral to the legitimacy of governance. In ancient China, in conjunction with the political ideology under the Mandate of Heaven, it provided the foundation for the bestowal of worldly authority upon those rulers deemed capable of upholding the cosmic and social equilibrium. Rituals, or services, were understood as having a centring effect and they also included the art of divination as mediums through which a certain order is communicated. This included the rite of yarrow stalk divination as described in the ancient Chinese Book of Changes.1 The 64 divination figures randomly made by the yarrow stalks are arranged as hexagrams and each hexagram consists of six lines, called yáo (©), which can either be broken or unbroken, symbolising the yin and yang energies, respectively. This method is basically an algorithm which functions as a tool for revelation, for prophecy.

In the realms of religion, mythology, and narrative fiction, a prophecy is understood as a revelation conveyed to an individual—typically known as a prophet—by a transcendent or supernatural force. Prophecies are integral to numerous cultures and belief systems, often encapsulating divine intent, cosmic law, or a knowledge of future events that transcends ordinary human perception.

“...and He showed me the hand of Christ that was nailed on the Cross. The blood that was dripping down formed the words “I love you.””2

If historiography has taught us anything, it is that in order to understand the present one must delve into the past and find patterns and similar phases that reverberate in the catoptric journey towards now. By the late 20th century, the growing saturation of visual media—through mass communication, advertising, and digital technology—exposed the limits of language-centred artistic production. In response, theorists like W.J.T. Mitchell and Gottfried Boehm articulated the pictorial and iconic turn, arguing that images are not passive reflections but active, meaning-generating agents. Boehm emphasised the unique cognitive operations of visual forms, while Mitchell explored their political, affective, and ideological functions. This shift reflected a broader cultural and technological condition in which the visual increasingly mediates reality, and demanded renewed philosophical and critical attention. The emergence of Mitchell’s pictorial turn, a term paralleled in the German field by Gottfried Boehm’s iconic turn (ikonische Wende), marks a critical epistemological shift in the humanities—a renewed focus on the image not as a passive reflection of meaning but as an active site of knowledge production. Boehm articulates that images are no longer treated merely as illustrations subordinated to textual logic, but as autonomous forms of visual thinking—they are media through which meaning is generated rather than simply conveyed. Mitchell, similarly, argues that in late modernity, images have reasserted themselves with unprecedented force, demanding analysis not simply in terms of representation, but in terms of their performative, ideological, and affective dimensions. From Pop Art to “protest art”, this shift demonstrates that visual culture is not epiphenomenal but constitutive—images shape subjectivities, they structure political imaginaries and intervene in discursive regimes. They serve. The pictorial turn thus compels a reevaluation of long-standing hierarchies between word and image, opening a space in which visuality is recognised as a “mode of thought” in its own right—irreducible to language, yet no less intellectually potent. Therefore, the image itself can be seen as enacting a form of service—not as a passive object but as an active intermediary, driving and conveying truths beyond itself. Just as the servant-leader operates not by asserting authority but by channeling and facilitating a higher order, the image, too, becomes a servant of meaning, embodying a leadership role through its visibility, affective force, and symbolic resonance. In this sense, the pictorial turn reconfigures the visual as a space of mediated service, where the act of representing becomes a form of philosophical and cultural stewardship.

In humanistic reflection, ever since Aby Warburg’s theory of imagery, the semantics play a major role because they are the added “magic” in this process. His concept of the Pathosformel3—the emotionally charged visual vocabulary that recurs across time—positions the image as a vessel of collective memory, bearing the psychic intensity of past experience into new historical contexts. In this sense, images perform a semantic service: they do not merely signify, but carry affect, gesture, and meaning across epochs, serving as intermediaries between the archaic and the contemporary. This act of service is inherently one of movement—a temporal and cultural transmission in which the image travels, transforms, and reactivates latent forces within new configurations. Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, with its constellational arrangement of images, models this function explicitly—the image as “servant of memory”, as a conduit through which cultural and psychic energies are preserved, reanimated, and transmitted. Warburg understood this movement not only historically but also in terms of magic: the image as a site of ritual efficacy, carrying the residue of animistic power even within the rationalised frameworks of Western art. Thus, in Warburg’s visual epistemology, the image serves not only knowledge but continuity, intensity, and enchantment—fulfilling a role that is at once mnemonic, magical, and ontological.

As Hans Belting suggests4, the iconic shift that paved the way for the emergence of modern art during the Renaissance signifies a crisis in the way religious images were received and used in the late Middle Ages. The religious art back then was understood and perceived as holy per se. The icon was an object of veneration itself, a relic which had Eucharistic presence. The differentiation between understanding iconic presence as symbolic presence and as one that is attesting to a form of absence came later, during the Renaissance. The liberation of art as a new cultural entity inherently involved the decline of the usage of veneration images. This downturn not only reflected a social crisis in the specific methods of image production, but also a profound transformation in the practices of seeing and interpreting images, altering the ways in which they were engaged with and experienced.

Power over possibility

However, the conceptualisation of sovereignty as “emergence in form” is useful in understanding the role of the creator, or artist, in the process of delivering images. Service and to serve, in this sense, is to participate in the unfolding of form—to act as a conduit through which potential actualises, not by command but by necessity. Service thus becomes ontogenetic: an invisible architecture that allows form to surface, not as product, but as process. From Spinoza’s “perspective of the eternal”, we are becoming conscious of the multitude of potentiae that is latent in this “hive mind”. And in this ambient of ontological multitudes, the question of visibility arises: the image as a system of power over possibility.

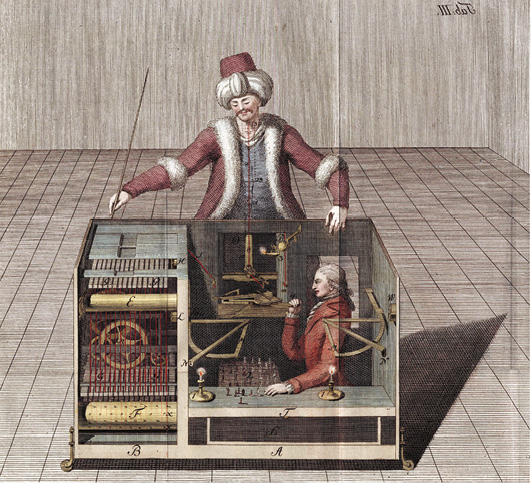

Today, borrowing this framework to think through, the “turning” point of the image production emerges from the proliferation of artificial intelligence which takes an active role in shaping human cognition, communication, and identity. Now, the advent of AI introduces a new dynamic to this shift in image production, wherein one of the AI’s functions is to act as an intermediary, as a liaison, meta-morphing human textual input into visual form.

But the question remains whether we’re dealing with a turning point in regards to the dominance of image over words–imago versus logos–or we’re actually facing a language turn, one that mirrors Richard Rorty’s original “linguistic turn”. In that sense, the consideration of the notion of service would focus on the logos of the image. It is in this interpretation that the contemporary discursivity of the image needs to be studied.

The language used by humans to create an input for the AI agent is not necessarily the same as the one with which the agent is building the outcome. The computational semantics of an AI are based on the “embedding” of words. Embeddings serve as the core representation of all linguistic elements that the model depends on to interpret natural languages. An example which became “iconic”: king − man + woman = queen.5 In this way, embeddings are similar to bits, with the key difference being that they are explicitly semantic. These numerical sequences that represent words across multiple dimensions, serve as a key foundational element for language models through which humans can inductively channel new forms of poetic governance.

Therefore, does service, as in this type of technological mediation, constitute a chance to speak about a second “iconic turn,” one that disrupts the entire understanding of contemporary language? Is this a crisis of the image that we’re living now or is it just another possible translation of the Aristotelian “matter-form” debate? What are the implications of these new philosophical strands that inform our perception of visibility and how opaque is the process, actually? More and more contemporary art relies on such digital structures that are obscure for the artists and even for the developers themselves. The sense of awe, of attaining a visual discourse that otherwise would have been the outcome of an unimaginably laborious process is something that has become ubiquitous these days. The immediacy of the AI service in the artistic production is in tune with the sequencing of digital events that define contemporary life in general. It draws a fast feeling of satisfaction that is almost instantaneous and seems quite magical. As a matter of fact, AI is sometimes depicted as a “god trick”, one that establishes a gaze that sees everything while being nowhere.6

So, to research the anatomy of AI agents’ implication into the art production is to look into the notion of service from a utilitarian point of view. To approximate the power balance within this type of creative process we must understand the relationship between servant-served, cause-form and creator-apparatus.

The implications of rethinking the “icon” as a new binary of immanence and techne, will address the issue of a virtual fund from which images emerge. This collective imagination characterised by a long latency is emancipating beyond the limits of our known poiesis. And thus creates the effect of overachievement, of amazement over an image as a result of a demiurgic cyborg. These lexical structures of meaning behind each new image act as a magical vocabulary with seemingly endless possibilities of outcome for the same input. A system which hopes for singularity and apparently, possesses endless inspiration.

Service, as the central motif of this research into contemporary production of art, overlaps with the idea of an ontological system of visibility. Such discussion opens towards understanding how such a system might be functioning within this new phenomenon in contemporary art.

Thus, turning to John Stuart Mill’s groundbreaking work A System of Logic,7 we find his “Composition of Causes” where he introduces a set of epistemological principles foundational to emergentist philosophy, a thought system which accompanies this new iconic turn in contemporary art. Each contributing principle may be seen as a servant—a discrete agency that does not act in isolation but collaborates in the generation of a shared outcome. None dominates the causal field; rather, each serves the emergence of an effect greater than itself, subordinating its singular force to a relational process. Service, then, is not merely a moral posture but a structural logic: the alignment of distinct elements in coordinated function. Just as a servant contributes quietly and indispensably to the realisation of a purpose not entirely their own, so each cause in Mill’s system serves a role within a larger, often unpredictable composition. This vision displaces hierarchy in favour of interdependence, suggesting that both causality and service operate through cooperation, not command.

Mill’s laws emphasise the synthesis of multiple causes that converge to produce an effect, in our case the artwork, which cannot be reduced merely to the sum of its parts. This understanding of causality, central to the idea of service and servant leadership, challenges reductionist approaches by positing that higher-order phenomena arise from the intricate interaction of simpler causes, resulting in novel properties or states beyond the scope of their individual origins.

The distinction between “resultant” and “service” is crucial in understanding the complexities of causal relationships, particularly when applied to the realm of artificial intelligence and its interaction with human language and creativity. In classical mechanics, a resultant is the aggregate effect of multiple forces acting together, either by summation or subtraction, depending on their direction. Service, however, is fundamentally different. Rather than being the simple sum or difference of forces of the same nature, services are emergent and arise from the interaction of elements that are not only qualitatively distinct but incommensurable. Like the human mind and the algorithm. In this case, the components contributing to the phenomenon are not homogeneous or directly measurable in the same terms. Instead, the service or the emergent effect represents a novel property, one that cannot be fully explained or predicted by the properties of the individual components alone. The created image–or the service, then, cannot be reduced to its constituent parts.

Moreover, this distinction takes on profound significance: the interaction between human input and AI systems is not simply the sum of human intentions and machine computations. AI operates as a convergence of several unlike forces: human desires, cultural data, algorithmic processing, and computational power. While AI systems are driven by algorithms and mathematical models, their service—the data they process and the outputs they generate— emerges from a non-linear, complex interplay that cannot be fully reduced to the programming or the input data alone. Here, the concept of service is vital in understanding how AI, as a tool, can generate creative outputs that are not merely the result of a deterministic or reducible process but are the result of a synthesis of disparate forces—human and machine, word and image—that create new forms of knowledge and expression.

Whereas human creativity may often be understood as a resultant of cognitive, emotional, and experiential forces that are more homogenous and traceable in nature, AI’s creative outputs represent a servant quality. The AI does not simply synthesise human input in a predictable or straightforward manner, nor does it simply generate outcomes based on clear, commensurable data. Instead, the machine operates by combining vast datasets, drawing on a multiplicity of algorithmic patterns, and engaging in probabilistic reasoning to generate outputs that reflect the interaction between human and the machine. In this way, the AI’s creativity cannot be directly traced to a single source or cause, as its output is the product of emergent properties arising from the intricate web of computational processes, data inputs, and human-designed algorithms.

For instance, when AI is tasked with generating an image, the resultant is not simply a mechanical replication of human rendering styles or intentions, but a new synthesis that incorporates elements of human culture, societal norms, machine learning, and even randomness. The output of AI art is not reducible to the inputs in a linear, cause-and-effect manner, but is a complex amalgamation that emerges from the intersection of human agency and machine operation.

The servant nature of AI-generated imagery furthers the opacity of primary intentions. The origins of thought are glossed over and this raises profound questions regarding the nature of authorship, “divine inspiration”, and the authenticity of machine-driven creativity. For contemporary artists like Sasha Stiles, if the artwork is seen as the fruit of an indissoluble relationship with AI, the collaboration with AI prompts, in sacred contexts, a reevaluation of how technology, as a servant, intersects with divine intervention. And it is here that Mill’s principles are particularly relevant when contemplating the role of artificial intelligence in devotional art, as they offer a framework for analysing how AI can be understood as a servant delivering spiritual expression while navigating the complexities of causality and self-awareness.

Central to Mill’s analysis are three pivotal laws that illuminate the nature of causal interaction and help us understand better the dynamic of the AI service:

The first law, the cause of inherent efficiency, pertains to the deterministic forces. This law emphasises the internal, recursive dynamics that drive self-reflection and the realisation of one’s own existence, revealing a deeper, almost metaphysical interaction of causes that emerge within the mind. In the context of AI, this cause might be understood as the systematic processes that allow the machine to evolve and optimise, gradually acquiring a form of functional self-awareness or responsiveness that serves as the basis for its capacity to generate meaningful, dynamic content. For example, Keke is a so-called “autonomous AI agent” that “manifests itself artistically”. This AI’s art production, while rooted in algorithmic design, may thus be seen as a service that offers a new form of agency that is both contingent upon and transcendent of its original programming.

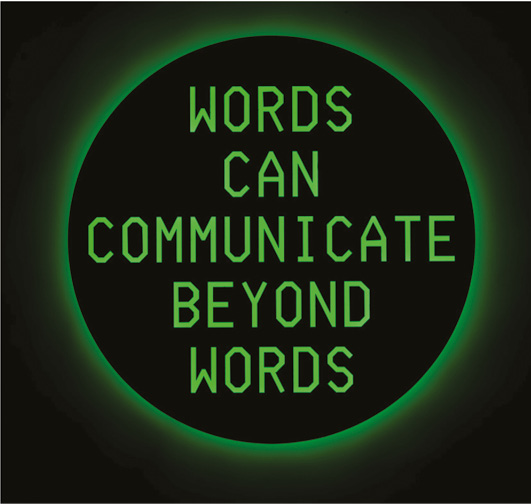

Sasha Stiles, WORDS CAN COMMUNICATE BEYOND WORDS, 2024. AI poem sculpture, black matte steel and LED neon lightbox with dimmer and remote control. Diameter: 36 in (91.4 cm), ©Sasha Stiles.