VOLUME

ISSUE 13

Weather

Weather, as we know it, is a geoscientific term that refers to atmospheric elements to which planetary inhabitants residing on Earth are subjected. Weather is an integral and integrative system that places humans and animals within the ecology of their habitat. Daily, we glance at the skies as we go about our ritualised chores or plan our activities around the everyday temperateness of the weather. Changing weather defines our everyday sense of being, and over long periods of predictability, it aggregates into the climate of our existence.

ISSUE 13

2024

Weather

ISSN : 23154802

e-ISSN : 3041-0924

Introduction

Exhibition

Essays

Conversation

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Weather

Exhibition

Everybody Talks About The Weather

Essays

Three Weather Reports on Burning Air

Monsoon Equinox

Conversation

Hà Nội: Weathered Art: Radical Instinct, Community resilience and forecasting in a post-colonial space

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy Editor

Weixin Quek Chong

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Editorial Board

Asst. Professor Felipe Cervera, UCLA School of Theatre, Film and Television, University of California, Los Angeles

Professor Patrick Flores, University of the Philippines

Dr. Peter Hill, Artist and Honorary Enterprise Professor at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne

Professor Janis Jefferies, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK

Dr. Charles Merewether, Art Historian, Independent Researcher, Curator and Scholar

Editorial and Publication Support Team

Malar Nadeson, Dr. Darren Moore, Sureni Salgadoe

Contributors

Peter Hill

Huy Nguyen

Janine Randerson

Dieter Roelstraete

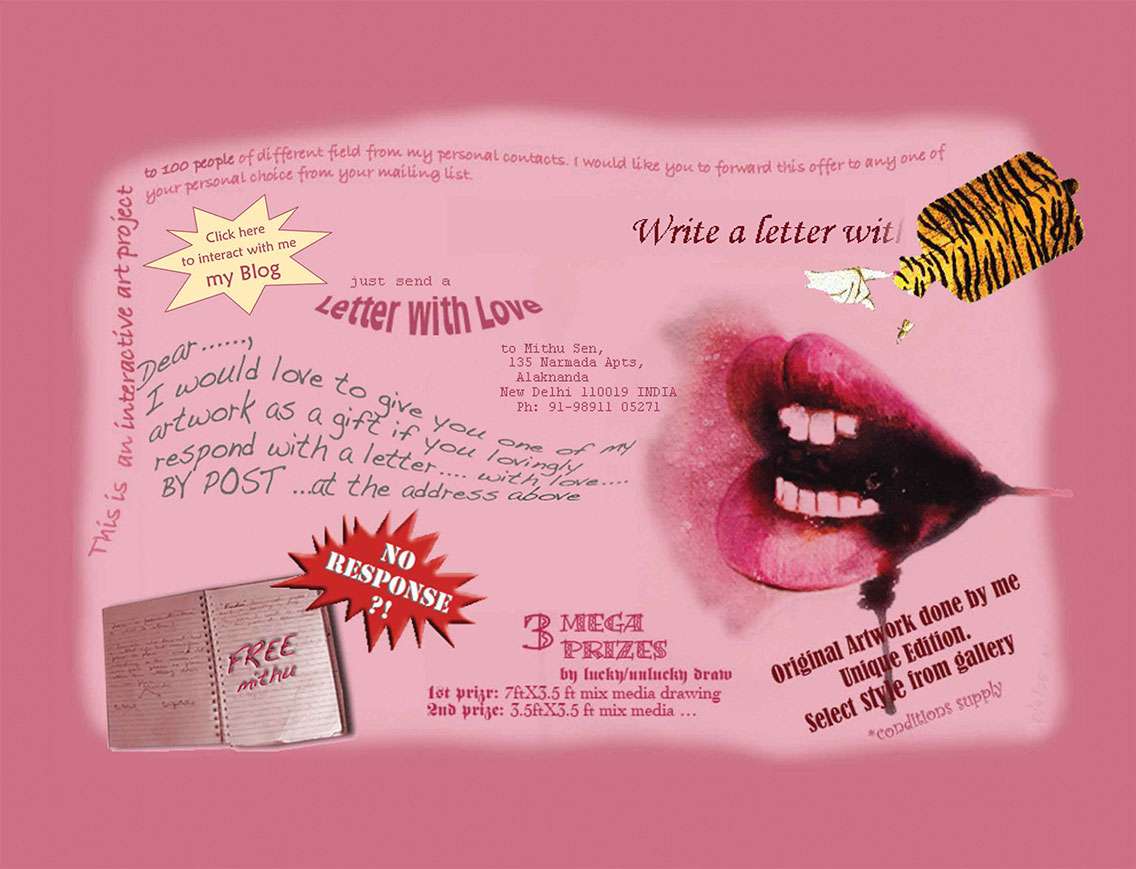

Mithu Sen

Soh Kay Min

Tran Luong

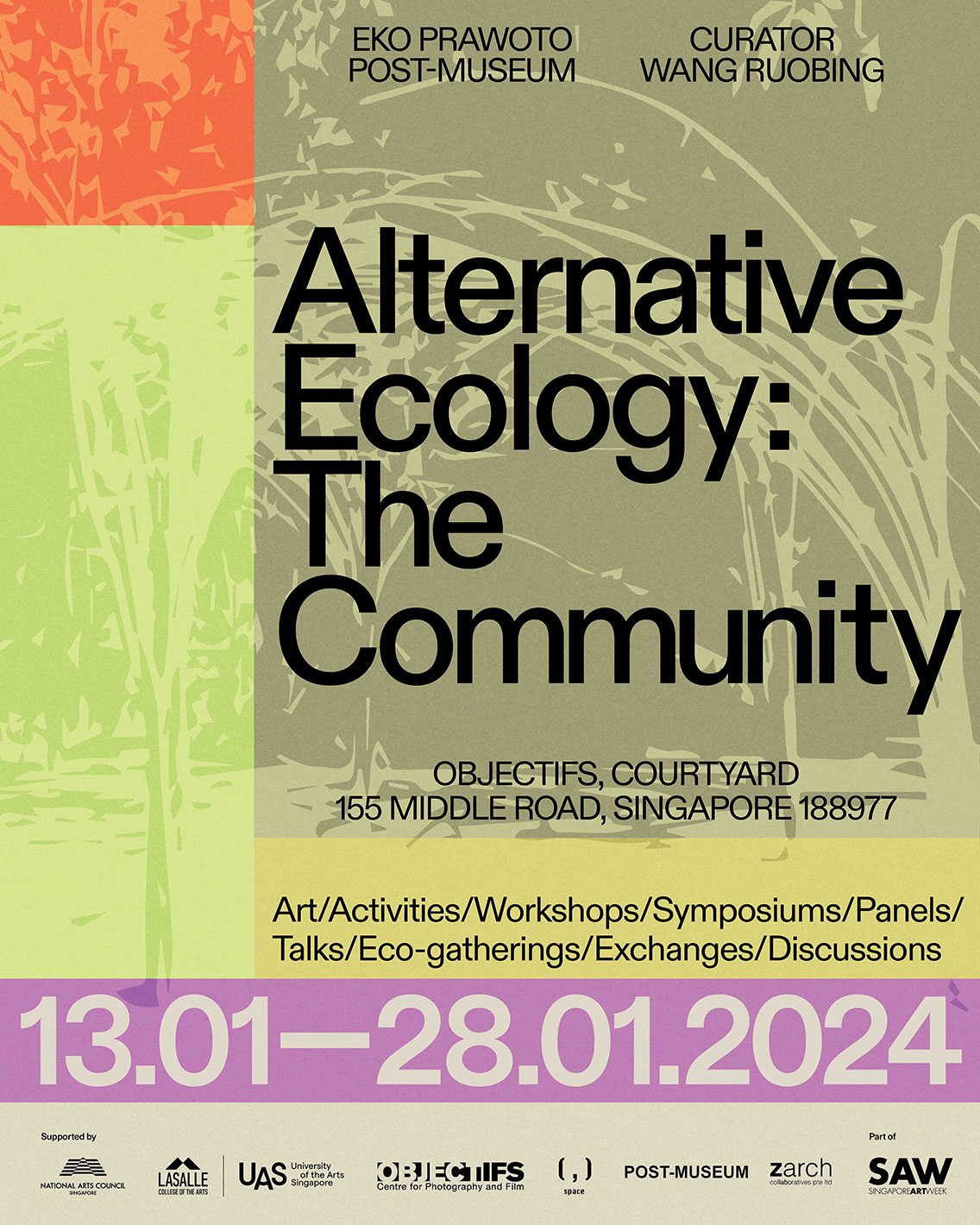

Wang Ruobing

The Editors and Editorial Board thank all reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments and feedback to the contributors.

Introduction

Introduction: Weather

The theme of Issue 2024 is the weather.

Weather, as we know it, is a geoscientific term that refers to atmospheric elements to which planetary inhabitants residing on Earth are subjected. Weather is an integral and integrative system that places humans and animals within the ecology of their habitat. Daily, we glance at the skies as we go about our ritualised chores or plan our activities around the everyday temperateness of the weather. Changing weather defines our everyday sense of being, and over long periods of predictability, it aggregates into the climate of our existence. Moreover, as a geoscientific condition, the weather has a significant existential impact on the environment as the Anthropocene besets the human condition -heightened by environmental shifts and crises.

Climatic conditions and weathering themes pervade everyday life. From art and poetry to linguistic metaphors to cloud computing, fecund thematic variations remain essential for describing the human condition. In art, the weather remains a source of idyllic and lurid engagement: the outdoors is observed; colours and light are gazed at; wind, rain and fire are stilled. The weather remains a source of observational training in reaching a realism that parallels an emotional epiphany, romance, melancholy or fear. As artists become deft conquerors of the morphing weather, art history etches a tamed environment subdued by ocular desires.

In contemporary culture, weather becomes a timely indicator of decisions and social practices. In politics, be it ‘fair-weather friends’ or the ‘tide in the affairs of men’ or war ‘hails’, the invocations and incantations remain potent and poignant. While concerns around climate change are at the forefront of contemporary discourse, scholars acknowledge how “profoundly this omnipotent force shapes culture”.1 For example, time is situated closer to the rapidity of weather forecasts than the long durational planetary orbit. In recent times, climate anthropologists have advanced significant theories around the social and embodied dimension of the weathered human body, where “climate change has to be related to global inequality.”2

In scoping the vast weathered landscape, the concept of weather remains notoriously current, providing metaphoric and atmospheric propensities to reimagine the human condition. Given this backdrop, weather’s thematic richness offers endless avenues for exploration and expression. This volume aims to delve into these multiple dimensions, examining how weather shapes, disrupts, and enriches the human condition. By engaging with this theme, we hope to foster a deeper understanding of how atmospheric phenomena influence not just the physical world but also the landscape of human thought and culture. In doing so, we aim to enrich our readers’ perceptions of weather, not just as a series of meteorological events but as a continuous, dynamic dialogue between humanity and nature.

Footnotes

1 Strauss and Orlove, 2021.

2 Eriksen, 2021.

References

Strauss, Sarah and Orlove, Benjamin S. Weather, Climate, Culture. Routledge, 2021.

Eriksen, Thomas Hylland. “Climate change.” The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Felix Stein, 2021. http://doi.org/10.29164/21climatechange

Exhibition

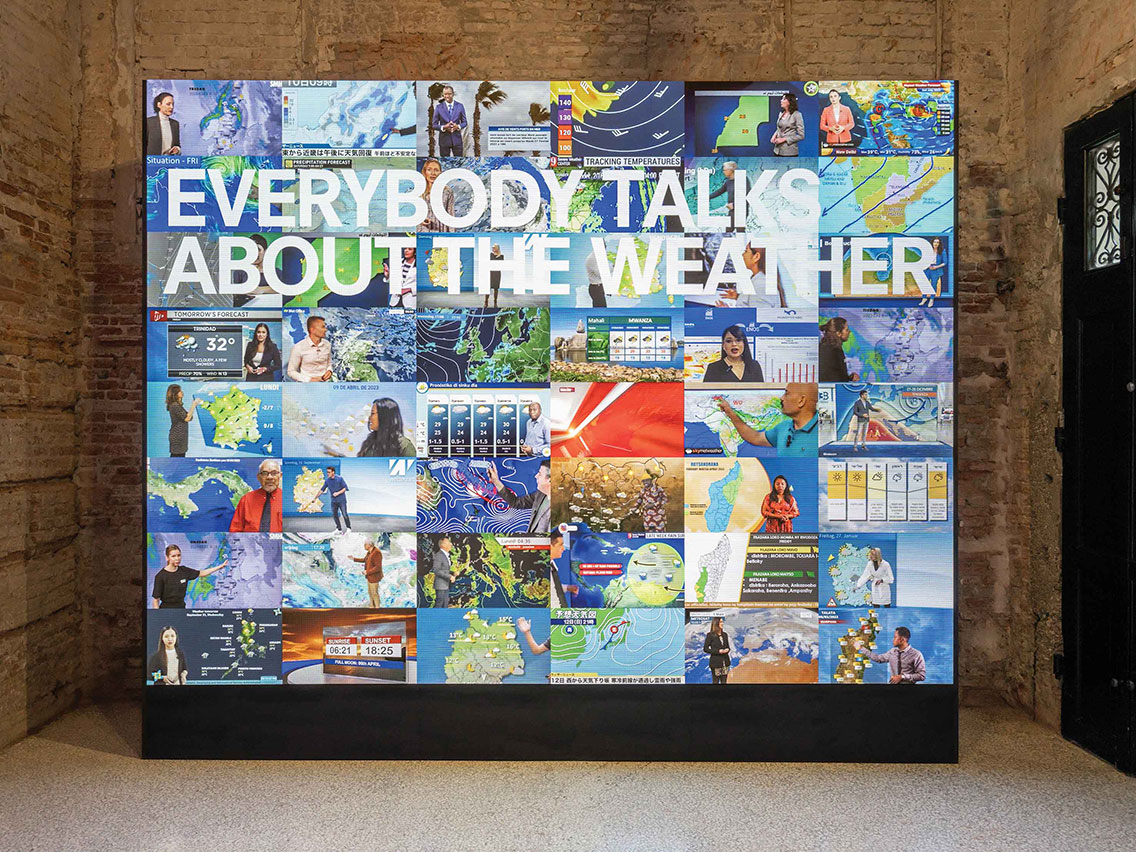

Everybody Talks About The Weather

I get the news I need from the weather report

—Simon & Garfunkel, The Only Living Boy in New York

The following visual essay is based on an exhibition I curated for the Fondazione Prada in Venice in the spring of 2023 in the broader context of that year’s Architecture Biennale. Staged inside the sumptuous interiors of the Fondazione’s 18th-century Ca’ Corner della Regina, the exhibition was rooted in the observation that, even though the current and ongoing climate crisis may well be the single greatest existential threat humankind has ever had to face in its 100,000-ye ar history, it remains a subject, paradoxically enough, that is oddly absent from the broad sweep of mainstream art world attention; one might even make the claim that the climate crisis has yet to spawn its first great corpus of critically acclaimed masterpieces, whether in the realm of visual art, literature, or cinema. It is evidently the very enormity of this crisis that is one major cause of this misplaced paralysis and sense of powerlessness – an unwillingness, in effect, to “talk about the climate crisis” which led me to suggest that we talk about the weather instead. Resorting to the seemingly mundane quotidian ritual of that most timeless and universal of discursive deeds, Everybody Talks About the Weather charts a modest history of art’s meteorological imagination from the 16th century – the nadir of Europe’s “little ice age” – to a present day that has become unimaginable without the endless reporting of one extreme weather event after another. Indeed, what do we really talk about when we talk about the weather? Can we ever regain the innocence with which the likes of Friedrich and Turner turned their gaze to the clouds, or do even Turner’s cloudscapes already speak of a paradise forever lost to the advent and onslaught of anthropogenic climate change? The answers to these questions (“my friend”) are blowing in the wind of our own making.

Dieter Roelstraete, Chicago, February 2024

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

Frozen Lagoon at Fondamenta Nuove 1708 (c. 1709)

Anonymous artists from the Veneto region

oil on canvas

95 × 129 cm

Venice, Fondazione Querini Stampalia

jpg to01 (2022)

Thomas Ruff

inkjet, DiaSec Face, wooden frame

251 × 186 cm

Ed. 01/04

Courtesy the artist ©Thomas Ruff /VG Bild- Kunst, Bonn 2023 / SIAE 2023

Storm (1969)

Alix Ogé

oil on canvas

48.3 × 63.5 cm

Stokes Haitian Art

Photo: Glenn Stokes

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

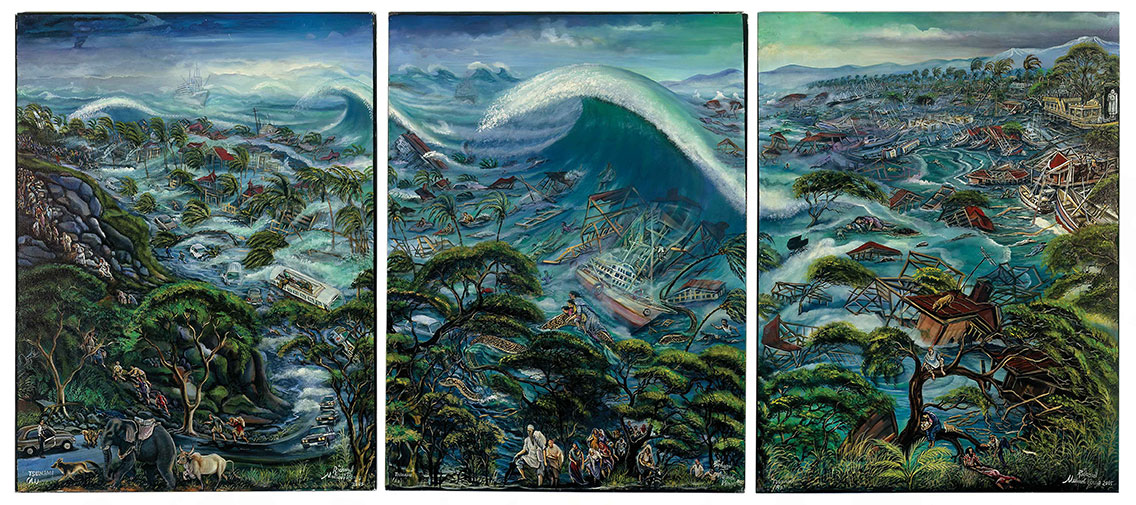

Tsunami (2005)

Richard Onyango

acrylic on canvas

160.5 × 365 cm

Geneva, The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection

Courtesy The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection

Photo: Maurice Aeschimann, Geneva

Horizon II (2014)

Antony Gormley

carbon and casein on paper

19.5 × 28 cm

© Antony Gormley, 2023

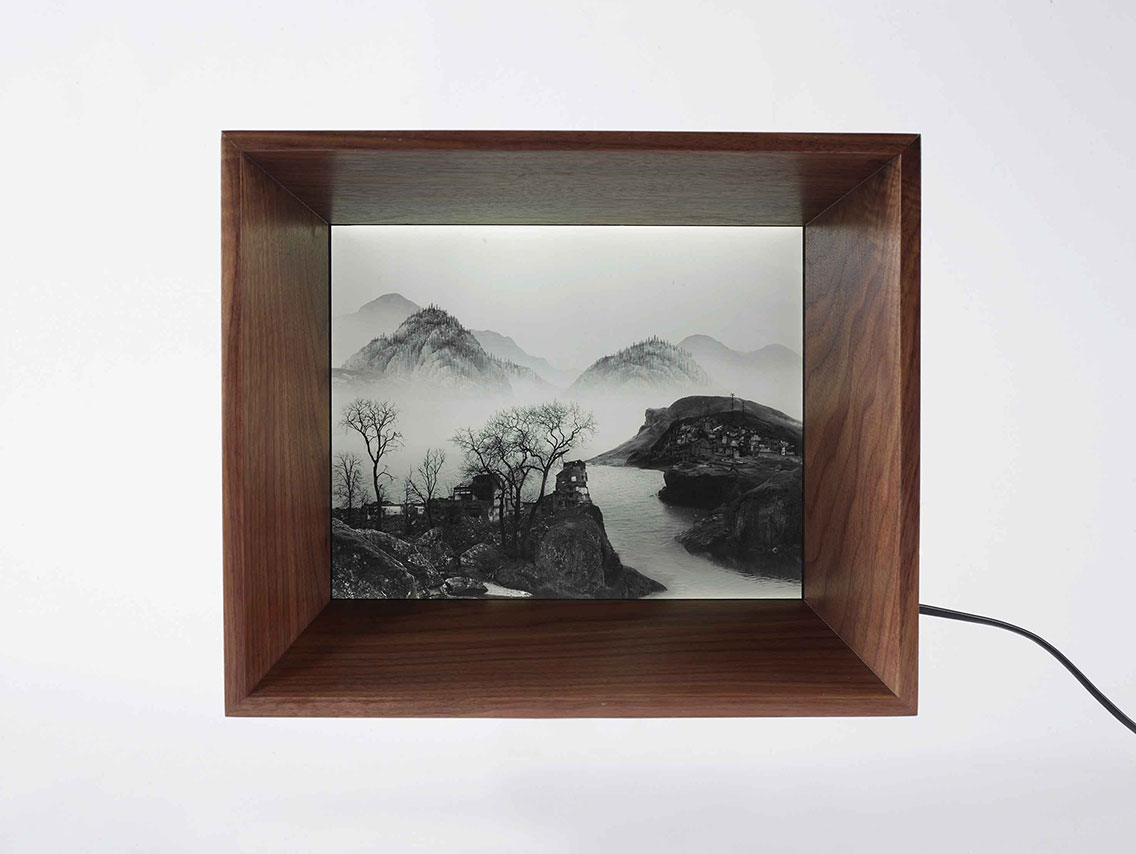

Time Immemorial – Other Shore (2016)

Yang Yongliang

film in lightbox, handmade wood box

20 × 20 cm (film size)

Courtesy Yang Yongliang Studio

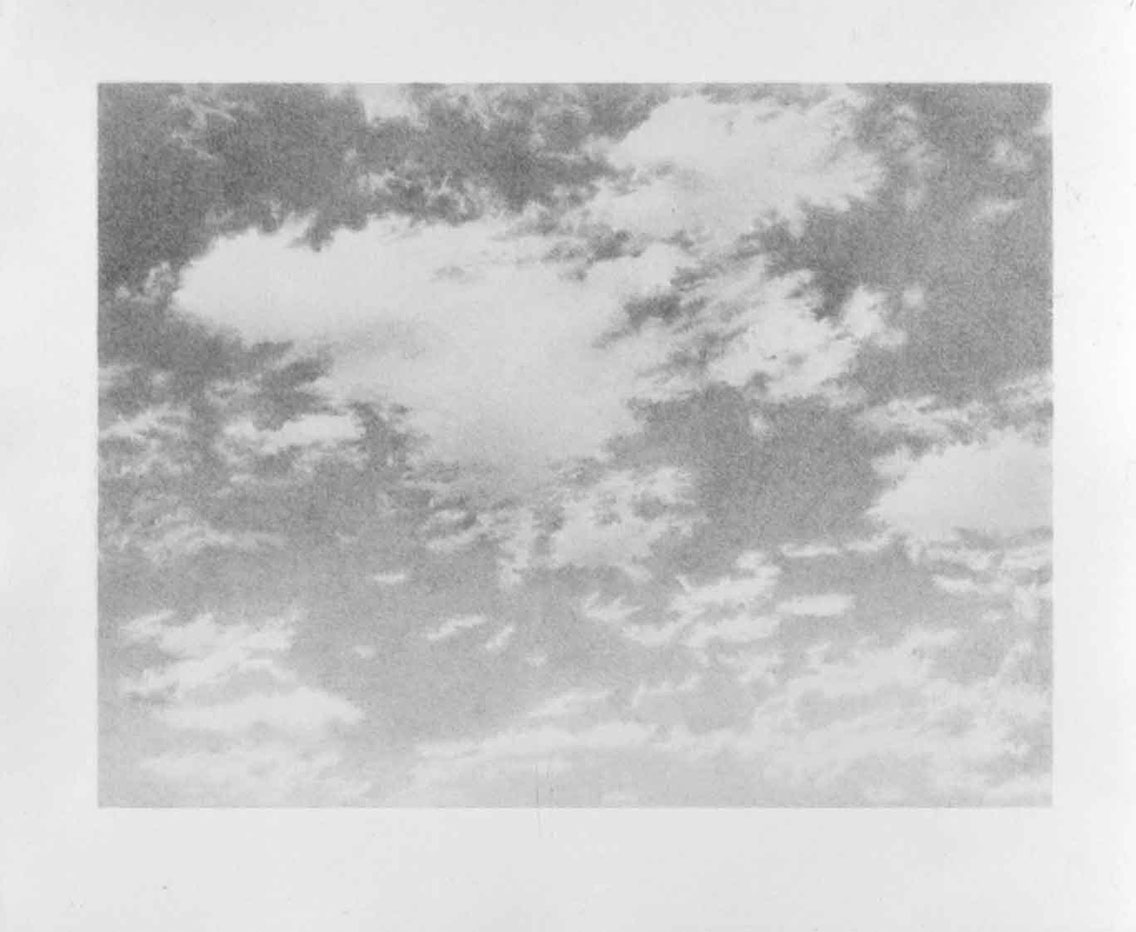

Untitled (Sky) (1975)

Vija Celmins

lithograph

42 × 52 cm

Los Angeles, Cirrus Gallery & Cirrus Editions LTD

Photo: Cirrus Gallery

Untitled (2018)

Chantal Peñalosa

6 diptychs from the overall artwork, inkjet prints on photographic paper

53 × 64 × 3 cm each

Courtesy Galería Proyectos Monclova & Chantal Peñalosa

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

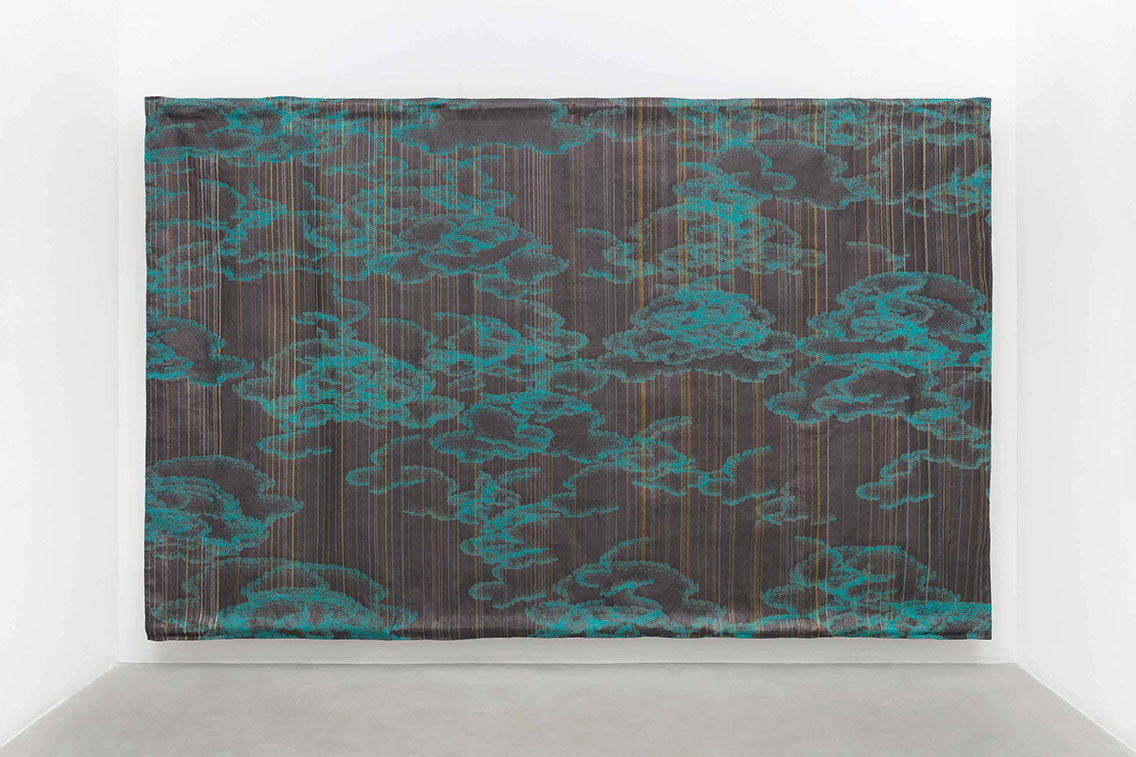

Kinked Rain / Gold (2022)

Pae White

cotton, polyester, Lurex 250 × 390 cm

Courtesy the artist and kaufmann repetto Milan / New York

Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Untitled (indipendenza studio #3) (2012)

Fredrik Værslev

primer, spray paint, corrosion on cotton canvas

220 × 200 cm

Private collection

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

Untitled, 2023

Pieter Vermeersch

oil on marble

32 × 52 × 2 cm

Courtesy the artist and P420, Bologna

© Pieter Vermeersch by SIAE 2023

Troubled Air: Tribute to Sunn O))), 2023

Pieter Vermeersch

A specially commissioned site-specfiic installation

Courtesy Galerie Greta Meert (Brussels), Galerie Perrotin (Paris, Hong Kong, New York, Seoul, Tokyo, Shanghai, Dubai), ProjecteSD (Barcelona), and P420 (Bologna)

Photos: Marco Cappelletti

Above credits for this page and next four pages.

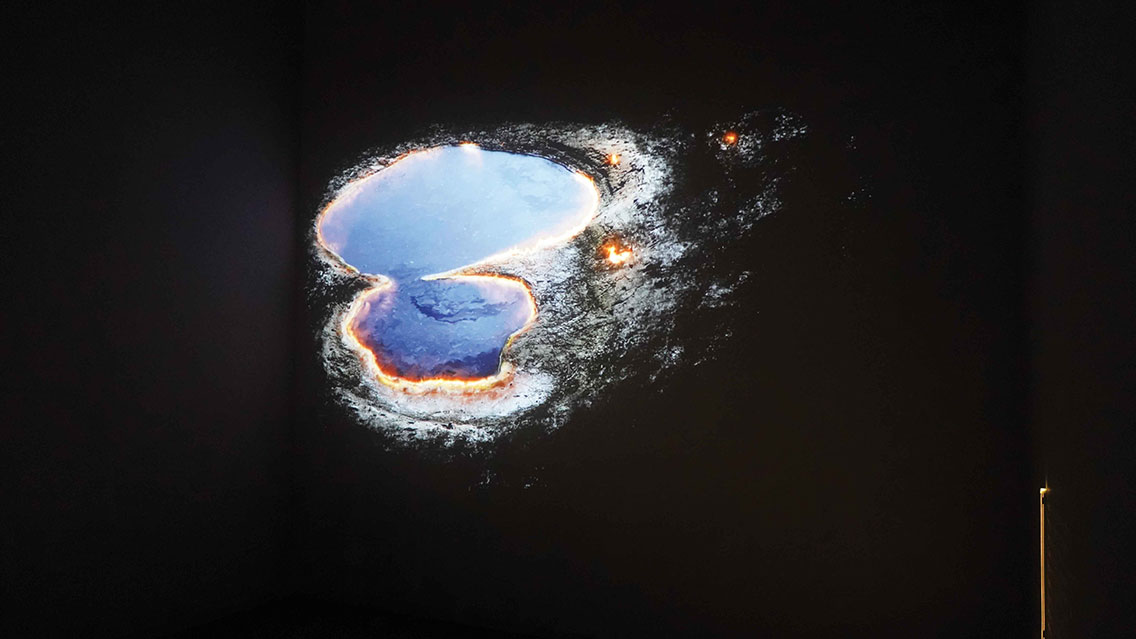

Deep Breath (2019/2022)

Raqs Media Collective

single screen digital video projection, 25’

Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London

Deep Breath film still 2019/2022

© Raqs Media Collective, courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

The Flood (2023)

Theaster Gates

colour video with sound 16’9’’

video still

Theaster Gates Studio © Theaster Gates Studio

Who Gave Us a Sponge to Erase the Horizon? (2022)

Goshka Macuga

woven tapestry

290 × 460 cm

edition of 5 + 2 AP

Courtesy the artist and Kate MacGarry, London

© Goshka Macuga by SIAE 2023

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

Going with Melting (2016)

Shuvinai Ashoona

coloured pencil and ink on paper

58.5 × 76.1 cm

Toronto, Dorset Fine Arts

Courtesy the artist

Photo: David Hannan

Plastic Horizon (w/distant weather event) (2014)

Dan Peterman

first generation post-consumer reprocessed plastics

40 × 52 × 6 cm

Courtesy the artist

Dan Peterman, Peterman Studio, Chicago, Illinois USA

Photo: Dan Peterman

How Does the World End (For Others)? (2022)

Beate Geissler & Oliver Sann

17 mounted and framed photographs, 37 mounted and framed typewritten pages

c. 1000 × 2500 × 50 cm

© Beate Geissler & Oliver Sann by SIAE 2023

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

In Kashan, Iran, Pari Soltani dyed wool the color of night

and wove the distance from above the weather to the earth

Jason Dodge

Courtesy the artist and Galleria Franco Noero, Turin

Untitled (2023)

Vivian Suter

mixed media installation

variable dimension

© Vivian Suter

Courtesy the artist and Karma International, Zurich; Gaga, Mexico City; Gladstone Gallery, New York/ Brussels; Proyectos Ultravioleta, Guatemala City; and Stampa, Basel

Photo: Marco Cappellitti

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

Interbeing Cloud 10.04 (2010)

Tsutomu Yamamoto

acrylic board, RGB, LED, glass, and MDF

91.2 × 45.7 × 11 cm

Geneva, The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection

Courtesy The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection

Photo: Maurice Aeschimann, Geneva

Moody (2019)

Nina Canell

lightning rod spheres (foreground)

Courtesy the artist and kaufmann repetto Milan / NewYork

© Nina Canell by SIAE 2023

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

A Wet Finger in the Air (2021)

Tiffany Sia

single-channel video 60’ in loop, infinite duration

edition of 3 + 2 AP

video still

Courtesy the artist and FELIX GAUDLITZ, Vienna

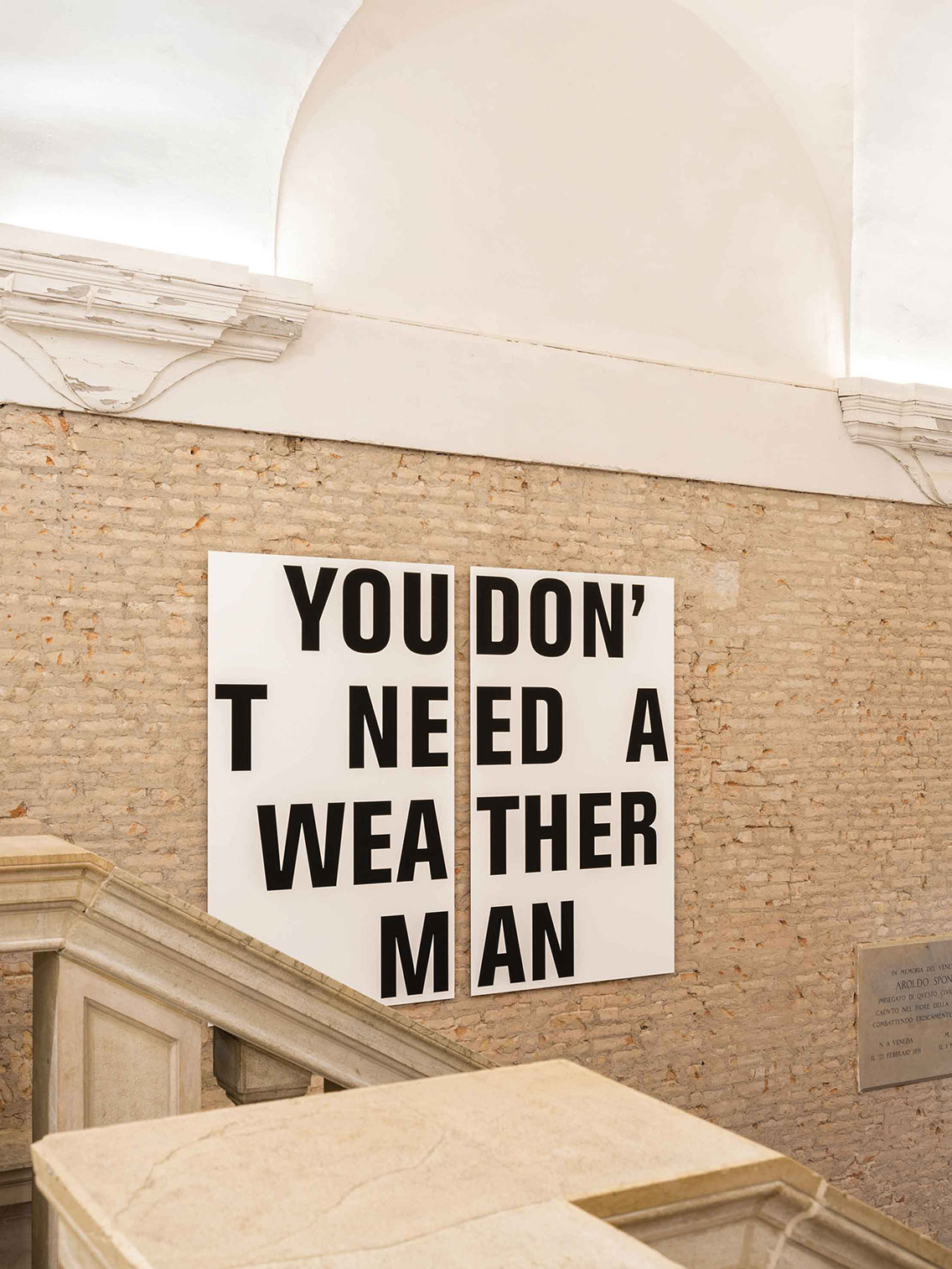

You Don’t Need a Weatherman (Version 3) (2017)

Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle

archival digital print mounted to panel

Diptych: 84.5 x 110 cm each panel

Courtesy the artist

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

Portrait of a Lady (c. 1640)

Carlo Francesco Nuvolone

oil on canvas

201.5 × 120 cm

Bologna, Collezioni Comunali d’Arte – Musei Civici d’Arte Antica di Bologna

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

Photo: Marco Cappelletti

Sun and Frost (1905–10)

Plinio Nomellini

oil on canvas

125 × 125 cm

Novara, Galleria Giannoni, Musei Civici di Novara

© Centro Documentazione Musei Civici

Artists in order of appearance:

La laguna ghiacciata alle Fondamenta Nuove (The Frozen Lagoon at the Fondamenta Nuove) was painted by anonymous Venetian artists in 1709.

Thomas Ruff (b. 1958 in Zell am Harmersbach, Germany) is a German photo-artist who lives and works in Düsseldorf.

Alix Ogé (birth date unknown) was a 20th-century Haitian painter.

Richard Onyango (b. 1960 in Kisii, Kenya) is one of East Africa’s leading painters.

Antony Gormley (b. 1950 in London, UK) is a British sculptor.

Yang Yongliang (b. 1980 in Shanghai, China) is a Shanghai-based artist trained in traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy.

Vija Celmins (b. 1938 in Riga, Latvia) is an American artist best known for her photo-realistic drawings of natural phenomena.

Chantal Peñalosa Fong (b. 1987 in Tecate, Mexico) lives and works on and across the border between Mexico and the United States of America.

Pae White (b. 1963 in Pasadena, USA) is a Los Angeles-based artist best known for her large-scale tapestries.

Fredrik Vaerslev (b. 1979 in Moss, Norway) is a painter working in the expanded field of abstraction.

Raqs Media Collective was founded in Delhi, India, in 1992 by independent multi-media artists and researchers Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula, and Shuddhabrata Sengupta

Theaster Gates (b. 1973 in Chicago, USA) is a multidisciplinary artist working at the intersection of social practice and installation art.

Goshka Macuga (b. 1967 in Warsaw, Poland) is a London-based installation artist widely known for her research-based projects.

Shuvinai Ashoona (b. 1962 in Cape Dorset/Kinngait, Canada) is an Inuk artist who works primarily in drawing.

Dan Peterman (b. 1960 in Minneapolis, USA) is a pioneer of ecologically themed installation art who lives and works in Chicago

Oliver Sann (b. 1968 in Düsseldorf, Germany) and Beate Geissler (b. 1970 in Neuendettelsau, Germany) work collaboratively in a range of photo-based practices.

Pieter Vermeersch (b. 1973 in Kortrijk, Belgium) is a color-field painter currently based in Turin, Italy.

Jason Dodge (b. 1969 in Newton, USA) is a sculptor and installation artist who lives and works on the Danish island of Møn.

Vivian Suter (b. 1944 in Buenos Aires, Argentina) is a Swiss artist who lives and works in Panajachel, Guatemala.

Tsutomu Yamamoto (b. 1980 in Okayama, Japan) is a Tokyo-based chronicler of natural phenomena at their most evanescent.

Nina Canell (b. 1979 in Växjö, Sweden) is a sculptor and installation artist based in Berlin.

Tiffany Sia (b. 1988 in Hong Kong) is an artist, filmmaker and writer living in New York.

Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle (b. 1961 in Madrid, Spain) is a Chicago-based artist primarily working in the expanded field of “social sculpture”.

Carlo Francesco Nuvolone (b. 1608 in Milan, Italy; d. 1662 in Milan, Italy) was the leading painter of the baroque in Lombardy.

Plinio Nomellini (b. 1866 in Livorno, Italy; d. 1943 in Florence, Italy) was a painter active in a range of post-impressionist styles.

Essays

Three Weather Reports on Burning Air

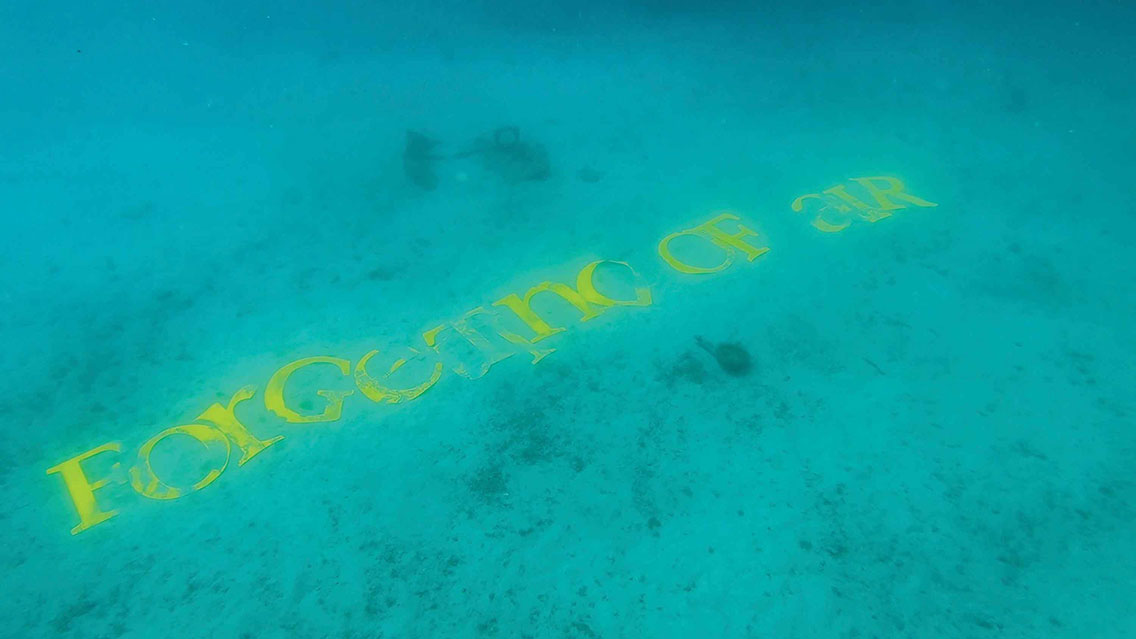

Our atmosphere is open and fluctuating, susceptible and conditioned by many human interferences; noise, industrial burning, exhaust fumes and our own exhalations. Weather emerges in momentary configurations of elements, energies, and forces, including the crowded, human-inflected air chemistry that effects catastrophic shifts in climate. I narrate a series of atmospheric encounters, weather reports of a kind, about three recent artworks that bear witness to our immediate and future weathers and the longer temporalities of climate heating. The first report is Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s collective ceremony To Burn, Forest, Fire (2021–2024); the second is Mithu Sen’s installation I Bleed River 2124 (2024) from New Delhi; and finally, theatre director Zuleikha Chaudhari’s fictional performance In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing (2023) that took place in Chandigarh.

I breathed in the aromas of Paterson’s incense burning ceremony in Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland, shared through the World Weather Network, a global network of artists, writers and communities responding to the climate crisis.1

Paterson’s ceremony, including incense sticks sent by mail, was performed over more than a year in many parts of the world, offering a collective moment of pause to inhale and remember the evolution of forest life through our lungs. I suggest that such sensorial actions fold into an understanding of the urgent action required of us all to mitigate the ecological crisis. In a recent visit to Delhi, I spoke to Mithu Sen and Zuleikha Chaudhari about their respective installation and performance works that foreground anthropogenic permutations of air. These two latter artworks were commissioned by Khōj International Artist Association in New Delhi, an organisation who are also part of the World Weather Network, and who have long explored questions around the role of art in atmospheric politics.

Weather appears as an artists’ live medium, yet weather always slips beyond our control, and now the runaway effects of climate crisis inflect every conversation about the weather. This article eddies around the weather conditions suffusing these artworks in a form of bodily climate witnessing.2 They each directly or indirectly advocate for the Rights of Nature, along with social justice, drawing rituals of breath, speculative aesthetics and ‘experimental jurisprudence’3 into their weather-worlding.

1 March 2023, 25 °, AQI 21, Cockle Bay, Aotearoa New Zealand

On a clear summer day, we lift back the orange-and-white-striped hazard tape surrounding the four-hundred-year-old pōhutukawa tree named Te Tuhi a Manawatere (the mark of Manawatere). I clutch Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s instruction booklet for the ceremonial artwork To Burn, Forest, Fire in my hand. James Tapsell-Kururangi has already set up the incense sticks that tightly hold the aroma of the first and last forests, along with a bell on a small wooden table. Commissioned by the Finnish art organisation, IHME Helsinki in 2021, a partner organisation in the World Weather Network, Paterson’s contemporary incense ritual To Burn, Forest, Fire4 is hosted in Aotearoa by Te Tuhi. Director of Te Tuhi, Hiraani Himona and I represent the World Weather Network programme, however the event is led by female Tangata Whenua, the Indigenous people of this place. Through mail, we (and a dozen or more small arts organisations in the World Weather Network) received Paterson’s incense sticks carefully packaged and with instructions. The IHME Helsinki commission emerged from Paterson’s practice of amplifying sensorial connection to our fast-diminishing natural heritage across vast time scales, from forests to glaciers, at this critical time of sixth mass extinction5 for plants and other species.

The sacred tree where we gather has been marked off with the orange/white tape by council tree workers as broken branches have just been removed. Within the last six weeks two severe cyclones—Cyclone Gabrielle and Cyclone Hale—have slashed a saturating and deadly path through the North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. People have died, animals have been washed away, houses have been destroyed, and many pōhutukawa trees have tumbled into the sea. These fallen giants once grew at perilous angles on cliffs in coastal regions, where their ropey spreading roots played a vital role in stabilising our shorelines. But edges of land once stable in the clement Holocene6 collapse in the carbon-soaked air and increasingly turbulent weather.

Today, the group is fanned by a light sea breeze. To begin To Burn, Forest, Fire, kuia (elder) Taini Drummond leads the assembled group towards the enduring tree. She performs a karakia, a ritual incantation. We sing a waiata, a song that Taini has composed for this ceremony, her words reaching back in time to the ancestor and astral traveller Manawatere who once marked this tree so future travellers by waka (canoe) would know the way to the shores of Aotearoa. Te Tuhi’s Pou Ārahi (principal cultural advisor), Carla Ruka plays pūtangitangi (flute) releasing gentle sounds that mingle with cicadas and the lapping sea. Taini leads us forward beneath the ancestor tree. The group of about twenty people, Te Tuhi’s elders, the perpetuals, quietly tread the carpet of leathery leaves and the low spreading branches. I slowly begin to read Paterson’s introductory text, and as instructed, I ring a small brass bell to commence the incense burning of the first and last forest.

James lights the First Forest, a bright green incense stick releasing scents from the oldest known forest in Cairo, New York State by the Hudson Valley, a forest that lived 385 million years ago. A thin curl of smoke mixes with the ozone from the ocean. The buried forest was discovered through fossilised root systems containing three types of ancient plant species, including Archaeopteris, which had well-developed roots, a large trunk and branches with leaves, akin to our pōhutukawa’s complex root systems. Paterson collaborated with the Japanese perfumers and incense makers Shoyeido, and with geologists to characterise these forests with aromas. The incense diffuses molecules of a very specific type including basic, identifiable elements from the ancient Devonian era environment before plants evolved to bloom with sugary flowers or fruits; the ancient forest soil was damp, the plants were something like what we know as mosses and ferns. There would have been no carpet of leaf-litter as there is today under our pōhutukawa, with its fingery red flowers, as deciduous species had not yet evolved.

One by one our assembled group inhales the incense scent of this transported ancient world. Carla Ruka has also set out a bowl of karamea, red ochre from a neighbouring soil, and each person dips their fingers in the pigment, then touches their hands to the ancient rough grey bark of the tree. Time becomes circular as we reenact the primordial mark of Manawatere. The touching is an attuning to the tree, to the many weathers the tree contains.

Katie Paterson, To Burn, Forest, Fire (2021–2024). An ancient pōhutukawa tree

named Te Tuhi a Manawatere is marked with karamea (red ochre) during the

incense ceremony hosted by Te Tuhi on 1st March 2023, Cockle Bay, Aotearoa

New Zealand. IHME Helsinki Commission 2021, shared on the

World Weather Network. Images courtesy of Te Tuhi.

I ring the bell again. When James lights the second, dark green Last Forest incense stick we are carried back to the present, to the scent of a living forest biome under threat from fire and human consumption: the Amazon Rainforest. For this aroma, Paterson’s collaborator, Dr. Ana María Yáñez Serrano introduced her research on airborne volatile organic compounds (VOCs) to describe the chemical constituents of the modern rainforest scents. The isoprene emitted by our pōhutukawa tree in Aotearoa melds with the molecules common to the trees and abundant plants in the Amazon. Yet the dozens of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes unique to the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve in Ecuador, permeate the atmospheric chemistry of the gathering here in Cockle Bay. The tingling scent of the Tiputini station in Ecuador is described by Paterson and her collaborators as follows: “a stunning array of scents, from the alcoholic fizz of guava trees to the fresh peanut-like aroma of the Earth, all combining in a unique sweet and bitter fragrance of the modern Amazon.”7 Like the Amazon, in the past two years we have been subject to flood and fire. The reverent quiet that falls over the group suggests a deep biome vibration with the uncertain fate of this forest far from us.

According to geologist David George Haskell: “When volatile molecules, those chemicals that we call ‘aromas’, enter our nasal cavities, they bind to fragile microscopic hairs on receptor cells. These cells then signal to the deepest parts of our brain, neural centres where memory, emotion, and a sense of time reside. Aroma moves us, working below and at the edges of conscious awareness.”8 The scent in the air carries us back and forth across time and space, just as the roots of the pōhutukawa conjoin recall the primordial roots of the Devonian forest. We float back to the time of the mark of Manawatere, the ancient, astral voyager who travelled on a waka made of feathers; and back further, ten million years, to the time when pōhutukawa trees evolved and spread throughout Te Moana nui a Kiwa, the Pacific, carried on ocean currents.

Our ceremony at Cockle Bay fused our breath with ancient and present forest airs, collapsing distance, decelerating us, recalling species and plants that have disappeared or exist precariously as wildfires threaten the Amazon. Paterson’s ceremony invites the deep inhalation of the carefully constructed particulate she releases, rather than the thoughtless volatile compounds spat out by cars or the factories chasing multi-national capital. The act of inhaling approaches what Astrida Neimanis and Blanche Verlie (2023) call: “a mode of more-than-human witnessing” of climate catastrophe. They argue: “...to breathe climate catastrophe is to witness one’s own body-in-and-as-part-of-the-climate. Put otherwise: we are the climate change we witness.”9 We become the ancient trees and tempests to come, they dwell within our bodies. This attuning might invite us to suppress our toxic emissions in our everyday lives.

2 February 2024, 14°, AQI 425, New Delhi, India.

The air is gritty with metallic soot; through grey-yellow fog, a limpid sun. A weather App sends me a ‘SEVERE’ air quality warning. It‘s raining in intermittent bursts on the opening evening of the group show 28° North and Parallel Weathers. The curators have set the provocation: “What World opens up to us when we think of the body as a site for attuned sensing?”10 Wetness pervades the three tiers of gallery spaces around the open plan courtyard of Khōj International Artist Association in New Delhi, where my collaborator Rachel Shearer is performing a live electronic audio composition on the rooftop.11 The dirt road came awash with a fast micro-flood of the urban village of Khirkee and the damp swept up my long skirt, tugging at my skin; the rainwater an ever-present mediator of this encounter.12 We are in New Delhi through our work with Te Tuhi, a sister independent contemporary arts organisation to Khōj and IHME Helsinki, again conjoined in the activities of the World Weather Network. After two years of remote conversations between artists, scientists and writers among 28 small arts organisations, the WWN platform was launched online in 2022. We met in the making of creative weather reports with artists, writers, performers and scientists. Our parallel programmes metabolise and forecast matters of art, environmental justice and social inclusivity.

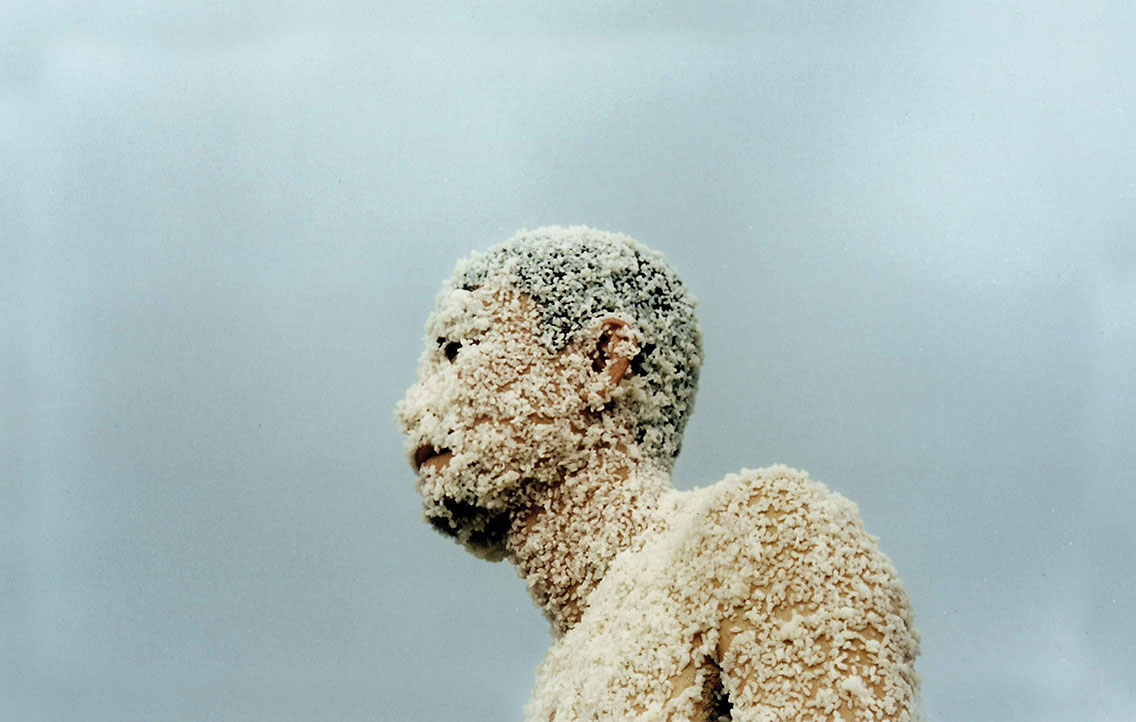

Mithu Sen, I Bleed River 2124. 28° North and Parallel Weathers, Khōj (2024).

Courtesy of Khōj International Artists’ Association.

I shelter at the edge of the courtyard with artist Mithu Sen, also exhibiting in Khōj. Sen is an inhabitant of New Delhi, born in West Bengal. As the rain falls heavily, we huddle in the reading room and talk about her installation I Bleed River 2124, where she traces the confluence of war and climate change. A projection of a burning river in toxic air dominates the room, while a smaller iPad narrates her journey along the present trans-boundary river, the Brahmaputra. The river, of rapidly diminishing width, and heavily compromised water quality flows through Tibet, Northeastern India, and Bangladesh, and has different names including the Luit in Assamese, Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibetan, and the Jamuna River in Bengali. For their World Weather Network project, Khōj invited artists to take a journey along the 28th Parallel North Latitude—which passes through Mount Everest in Nepal, the Northern Himalayas with Rajasthan in India and the Sindh Desert in Pakistan. This imagined cartographic line is an entry point for Sen and other artists in this exhibition at Khōj to speculate on future weathers of the ongoing climate crisis and the violent nature of the increasingly militarised human borders across the continent. A neon tube leads us from the gallery’s interior to the external courtyard and the date 2124, one hundred years from our wet present. Sen’s accompanying text reads:

Once upon a date, there existed a river named River sacrificially immersed in a distant inferno sparked by bombings, fundamentally altering the narrative of what was once known as a river. The flames from a faraway bombing ignited the river and became a transformative force, shaping a new storyline for this ethereal being in a tangible setting.13

In the Weather Glossary of artists’ terms that accompanies the exhibition, Sen has recorded the latitude of locations of 21st century wars: Baghdad; Gaza strip; Khartoum; Mariupol; Myanmar, West Bank and timestamps in the artwork draw parallels between the point at which they have been recorded in India. Sen’s speculative installation forecasts deadly flames from missiles dropping like rain from the air, recalling philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s ‘dark meteorology’ that attempts to destroy the combatant’s environment through poisonous gas.14 Anthropogenic wars collide with indifference to the changing climate.

Weather Glossary, Reading Room at Khōj. 28° North and Parallel Weathers, Khōj (2024).

Courtesy of Khōj International Artists’ Association.

The morning after the deluge, we visit the India Art Fair in Okhla, New Delhi. Passes scanned and bags x-rayed, we arrive to the vibrant commerce of the Art Fair halls on the once densely populated flood plain of the Yamuna River. Residential colonies in the narrow dirt lanes of have been rezoned as the NSIC Exhibition Grounds15. Outside swarms of dust, insects, circling kites (avian predators), jacket-wearing dogs and people subsist in barely breathable air. This is February in Winter: the air will become even more thickly laden with particulate matter from the agricultural fires of late Autumn. Cloggy molecules from exhaust fumes and factories cling to the remaining oxygen in the air, exacerbated by the naturally occurring fogs of low-lying Delhi.

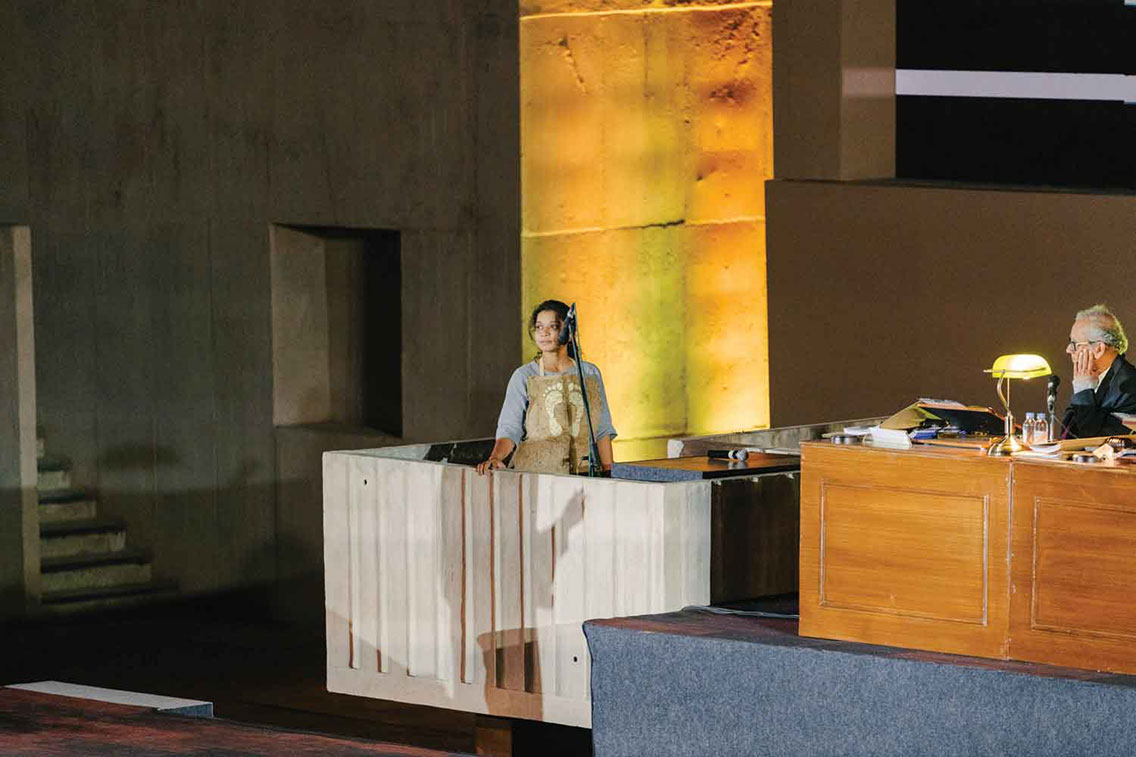

In a knot of people after an intensive panel on the political agency of art, I meet theatre director Zuleikha Chaudhari and we stand out of the fray for a short, intensive conversation.16 She is the artistic director of the performance In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing, a fictionalised court case conceived with Khōj International Artists’ Association in collaboration with lawyer Harish Mehla.17 The hearing on the corruption of the air is staged at the Open Hand Monument at Chandigarh in the golden light of evening refracted through smog. Chandigarh serves as the shared capital of Punjab to the north, west and the south, and Haryana to the east, regions where farmers were forced into unsustainable practices of stubble-burning by the conversion of the water-intensive wheat and rice-growing areas in the 1950s. Water can only be used for three months of the year so this intensifies multi-cropping on arable land from paddies to wheat fields. Multi-cropping demands fast turnover of crops and clearing by fire of the stubble-remnants each season. The unbearable air that this burning practice causes is brought to the performed court for a hearing filed by Khōj International Artists’ Association, Zuleikha Chaudhari and Maya Anandan, represented by her mother and legal guardian, Ms. Radhika Chopra.

In multiple languages, Hindi, Punjabi and English, the staged performance revolves around the Rights of Nature as an extension of the Right to Life within Article 21 of the Constitution of India. The hearing is enacted by actor-lawyers, real artist-activists involved in relational art practices with farmers, and a fictitious Farmers Union, whose livelihood has become dependent on stubble-burning. While taking place in the thickness of open air, the hearing still adhered to the legal protocols and procedures of the National Green Tribunal in order to explore principles of natural justice. The script developed with Harish Mehla took several years to write and drew on previous trials and collected testimony. Collectively the complainants indict the Union of India through the Ministry of Environment. The human-mattering of air, the matter of justice for the biosphere, and the social toll on humanity suffuses the arguments put forth by these three parties. The atmosphere of Delhi and Chandigarh appears as a modernist haze, which according to Steven Connor, “brings the sky down to earth, or dissolves the grounds of the earth, dissolving the relations between sky and earth, creating interference patterns between high and low, frontality and immersion. The meaning of modernist haze is the loss of the sky – or, at least, the loss of its distance, its aura of unapproachability.”18 In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing enacts these real losses.

This hearing is “theatre but not theatre,” reflects the director of Khōj, Pooja Sood.19 Several of the actors making submissions to this quasi-fictional court hearing are environmental campaigners who have filed many real petitions to the government to uphold the Environmental Protection Act of 1986. ‘Real’ actors including three practising lawyers, Manmohan Lal Sarin, Mannat Anand, and Harish Mehla, appear before the court in the hearing. In addition, there were three subject-expert witnesses, Kahan Singh Pannu, Manish Shrivastava and Tarini Mehta, who is an Associate Professor of Environmental Law. Three ‘real’ retired judges complete with stiff white collars and dark gowns play themselves: Justice Rajive Bhalla, Justice Kamaljit Singh Garewal, and Justice K Kannan.

The artists, also playing themselves in the hearing, foreground their artwork as ecological testimony and social practice to bridge the urban and rural divide. They are artist and performer Shweta Bhattad, filmmaker Randeep Maddoke, and the duo Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra. Thukral and Tagra‘s (T&T) creative practice spans data visualisation, gaming, archiving, and publishing. While their early work dealt with the politics of consumer culture, their recent interest in ecology and climate change involved revisiting their own family histories of migration and farming in the state of Punjab. While in New Delhi I visited Sustaina (2024) at Bikaner house, an exhibition curated by T&T and Srinivas Aditya Mopidevi which foregrounded artworks, ‚grass roots‘ designed artefacts and materials that offer ways through the ecological crisis. A constitutive building material used throughout the exhibition for display was formed from wheat stubble, posing an alternative second life to ash and atmospheric particulate.

Khōj International Artists’ Association with Zuleikha Chaudhari,

In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing. Chandigarh (March 5, 2023).

Courtesy of Khōj International Artists’ Association.

During In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing in Chandigarh, T&T presented a board game as part of their testimony that traces the traumatic experience of women farmers whose husbands have been driven by suicide due to untenable farming conditions. They worked closely with women of the Punjab to understand the economy of loss through the failure of family crops as the climate changes, and also to understand how they survive. As part of T&T’s testimony, one round of their game entitled Weeping Farm was played by drawing cards and moving around the board, enacted in the court itself. When a card is drawn indicating cyclonic rain for instance, a player loses ground and moves back several places, embodying a rural character’s daily life through the seasons. Through empirical research the artists discovered the tragic statistic that every 40–45 minutes there is one farmer’s death by suicide, and this timeframe determines the length of the game. Weather circumstances and cycles of cropping are critical to the lives of the surviving widow-farmers but they are trapped in an end game; they cannot separate their livelihood from the changing climate.

Artist Shweta Bhattad, dressed in a raw cotton worker’s apron printed with a footprint, presented a video of the turning pages of a handmade book as evidence: The Eaten Cotton...A Love Story...A Cook Book (2022). The soft raw cotton, screen-printed book is an illustrated encounter between cotton-growing, weather and culture, a material witness to ecological upheaval.20 Bhattad is a founding member of the Gram Art Project Collective, a group of farmers, artists, women and makers who all live and work in and around the village of Paradsinga. The story, told in letters, follows two characters through the origins of cotton cropping to the realisation of the demand to relinquish the boundaries between human and non-human, old and young, city and village in order to survive: a collective concept developed through the Gram Art Project, signalling a return to Indigenous knowledges.

Khōj International Artists’ Association with Zuleikha Chaudhari,

In the Matter of the Rights of Nature–A Staged Hearing. Chandigarh (March 5, 2023).

Courtesy of Khōj International Artists’ Association.

The final artist-witness Randeep Maddoke’s film, Landless, documents the caste dynamics and bleak conditions for Dalits, agricultural workers in the Punjab region, including itinerant goat-herders in an unfolding ecological crisis. The three artworks each have in common a socio-relational human struggle with the new weathers, providing experiential testimony of an uncertain future. This project continues Khōj’s concerns with creative forms of testimony in many projects since Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness (2017).

The testimony of artists in the hearing, alongside the environmental lawyers and the farmers responsible for the burning, demonstrates how art in the form of “experimental jurisprudence” ignites the public sphere and calls for real change to be effected. Artists invent forms of experimental jurisprudence when legal and State mechanisms fail, to cite a phrase T.J. Demos developed in relation to artist Amy Balkin’s atmospheric propositions to the U.N.21 This might also be extended to the non-human: an owl alights on the Open Hand monument at the beginning of the video document of the hearing—an assembly across species divides. The owl might say, it is not only human bodies that are suffocating silently, look at us in the skies. At the end of the trial the judges affirm the claimants call for the rights of nature, and call on the whole nation, represented by the government to respond, rather than any one community. A “compromise settlement” is reached. Zuleikha tells me urgently that the next step is to take this fictional hearing concerning the rights of air to the real National Green Tribunal. Later that night, our group walk passed the arched green-lit, yet faded gate of the National Green Tribunal, a legislative body effectively suppressed under the government of Narendra Modi.

Experimental Jurisprudence and the Rights of Nature

Both Aotearoa New Zealand and India have pioneered radical environmental jurisprudence; considering the legal personhood of rivers and forests. The laws in both the immense continent of India and my tiny island are rich in protections of ‘Naturehood’, however, their implementation is poor. In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing reflects an ecocentric turn in the last decade in juridical thinking in India, even if the implementation of environmental protection has been poor. Economist Rita Brara (2017) argues that India has “made some steps toward navigating an ecocentric course, even if intermittently, by experimenting with a language for the Rights of Nature that draws on India’s Constitution, the drift of international currents and treaties, the judgments of its apex and provincial courts, as well as the rulings of a green tribunal.”22 Brara suggests further that many of the religious and ethical traditions of the Indian peoples that venerate nature appear in their juridical thought. She notes: “The notion of dharma, translated as ‘conduct’ according to inherent qualities or character, is understood to characterise all of Nature. [...] Nonviolence or ahimsa, too, continues to be an influential strain of thought in Indian religious traditions and affects the judicature as well.”23 In indigenous Māori worlding from Aotearoa New Zealand, weather elements are also ancestors and empathise with or affect human circumstances; the weather atua, supranatural beings, may be called or herald the oncoming weather. Artists trace the temporalities of weather in our bodies and in machinic data sets as well as legal systems.

In a judgment by the High Court in the province of Utttarakhand, Northern India, the ground-breaking law to recognise the legal rights of personhood to the Whanganui River in Aotearoa New Zealand was cited (2017). The court declared that since the Ganges and the Yamuna are sacred to a large number of Indians, these rivers should be accorded the status of living entities and granted the rights of a juristic or legal person in March 2017. However, the judgment of the provincial court at Uttarakhand was overruled by the Supreme Court of India in July 2017 on the grounds that it interfered with the rights of other provinces and raised issues concerning who would be regarded as responsible for compensation if the rivers were to flood.24 In relation to flooding of the Whanganui river, these objections have yet to manifest.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the current right-wing government under Prime minister Christopher Luxton has repealed incentives for clean-cars, removed petrol taxes and smoke-free goals in his first 100 days in office—ecocidal acts of revenge politics following an era of centre left-government. The planet-upheaving cyclonic weathers that continue from these brutalist policies force bodies, biota and technologies into new assemblies.

Aerial Revolution

The art projects encountered in this narrative foment an aerial revolution that comes from the ground, from the breathers of air. They rally us to face the changing climate via the senses, to see the body itself as a sensor, and to reconstitute the impossible air of the present. Although weather is inconstant, it is crowded with substances, memories, and histories. As Connor has argued, the atmospheric science of urban meteorology has shown that since the 19th century the atmosphere “...is not just affected by contamination and irregularity—it is constituted by it.”25 When the exhausted air is filled with exhaust fumes and fog becomes smog, our bodies become smoggy through the act of respiration. The effects of the changing climate, visible and tasteable in the air, are symptoms of violent systems of power including the capitalist-colonial legacy in India, Aotearoa New Zealand and everywhere else. To recognise the rights of air is to guarantee our future survival along with our co-species.

When I left New Delhi I unspooled a trail of fossil-fuelled molecules from the petrochemistry of ancient forests. I left behind people living air-conditioned lives, and many others with no choice but to live at the roadside, always living in the air, in the exhaust of those who can move on. Yet in the thick air of my memory is also the scent of spices, the deep call of oud, and the light particles in ancient mosques swirling through porous panels. Within the clean-dirty spaces of aeroplanes, climate-controlled shopping malls and art fair exhibition halls we exist in modified weathers, buried in the staleness of regurgitated machinic air. Of fossil-fuelled travel, Connor writes: “For a mobile people, waste is the past.”26 Although this flight to India was my first long haul plane trip in six years, and a journey for which I weighed up the benefits of my presence as an artist and researcher, my carbon trail in the upper atmosphere, absorbed into the ocean, is the incontrovertible, biophysical thing: along with the Delhi air carried to the other side of the world inside my lungs.

The willing inhalation of incense in Paterson’s To Burn, Forest, Fire is an active co-respiration with trees and other species, or conspiration, an embodied form of witnessing to follow Neimanis and Verlie. The ceremony accentuates the simple biological connection we have to the respiration of trees through our breath. On the other hand, we are powerless to control our inhalation of unwanted atmospheric toxins without changing our fundamental desire for mobility and consumption. Neimanis and Verlie state:

We breathe together to survive, to empathise where possible, to recognise incommensurate suffering, to connect and entangle with others through shared breathing, and to create knowledges and responsibilities for breathing new worlds into life. Conspiratorial witnessing is therefore a breathy practice of collective action for climate justice.27

Air is now laden with compounds, it is a matter of concern never intangible or separate from culture; our atmosphere is becoming untenable for life, we breathe our waste. Artists witness, testify and speculate in powerful biophysical connections to weather as medium. Such artworks reflect the labour of extraordinary and radical thinking through experimental forms of environmental justice as in In the Matter of the Rights of Nature—A Staged Hearing; rituals in the case of Katie Paterson’s To Burn, Forest, Fire; and real politics fused with future speculation in Mithu Sen’s I Bleed River 2124.

6 February 2024, 21°, AQI 370, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, New Zealand

No sooner had I arrived home when my phone pinged in an emergency alert: my suburb was on fire; close all the doors and windows to keep safe from toxic smoke. Out of sight on the industrial edge of town a refuse station was burning, the winds carrying the unwelcome airborne matter of burning plastic to my home. While last Summer the cyclone-drenching floods swept my city and pōhutukawa trees and homes slipped into the sea, this Summer of 2024 a drought and hot El Niño winds have caused a fire to escalate. For three days the sound of helicopters fills the air, heaving monsoon buckets of sea water from the harbour to dowse the flames.

Footnotes

1 https://worldweathernetwork.org

2 Neimanis and Verlie, “Breathing Climate Crises: feminist environmental humanities and more-than human witnessing,” 2023.

3 T. J. Demos, Amy Balkin: (In)visible Matter, 2013.

4 Katie Paterson, To Burn, Forest, Fire, IHME Helsinki Commission 2021 (2021-2024). The IHME Helsinki Commission has taken place in 40 ceremonies in 15 different indoor and outdoor places from September 2021 in Helsinki to diverse audiences, https://worldweathernetwork.org/report/toburnforestfire/

5 “Palaeontologists characterise mass extinctions as times when the Earth loses more than three-quarters of its species in a geologically short interval, as has happened only five times in the past 540 million years or so. Biologists now suggest that a sixth mass extinction may be under way, given the known species losses over the past few centuries and millennia.” - Barnosky, A.D., N. Matzke, S. Tomiya, G.O.U. Wogan, B. Swartz, T.B. Quental and E.A. Ferrer, Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? 2011.

6 The name given to the last 11,700 years of the Earth’s history.

7 Text adapted from Katie Paterson. Maguire, Salonen and Zalasiewiczi, Art meets geology.

8 David George Haskell, “On the aromas of the first and last forests.” In Katie Paterson, Instruction Booklet 6.

9 Astrida Neimanis and Verlie 116-117.

10 Nerea Calvillo, “Political airs: From monitoring to attuned sensing pollution.”

11 See 28° North and Parallel Weathers. https://khojstudios.org/event/28-north-and-parallel-weathers/

12 Janine Randerson, Weather as Medium: Toward a Meteorological Art.

13 Mithu Sen, I Bleed River 2124.

14 Peter Sloterdijk, Terror from the Air.

15 National Small Industries Corporation.

16 Art and Agency. Panel including Khōj’s director Pooja Sood, Monica Bello (Cern), Professor Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Nidikung and Shuddhabrata Senguputa of Raqs Media Collective. India Art Fair, 2 February 2024.

17 Khōj International Artists’ Association, https://worldweathernetwork.org/report/khoj-report-2/

18 Connor 192.

19 Pooja Sood, Janine Randerson, Indranjan Banjeree, Alina Tiphagne, Conversation in the Khōj canteen 29 January, New Delhi, 2024.

20 Susan Schuppli, Material Witness.

21 T. J. Demos, Amy Balkin: (In)visible Matter.

22 Brara, “Courting Nature: Advances in Indian Jurisprudence,” 31-32.

23 Brara 32.

24 Brara 35.

25 Connor 191

26 Connor 272.

27 Neimanis and Verlie 118.

References

Brara, Rita. “Courting Nature: Advances in Indian Jurisprudence.” RCC Perspectives, No. 6, Rachel Carson Center, Munich, 2017.

Barnosky, A.D., N. Matzke, S. Tomiya, G.O.U. Wogan, B. Swartz, T.B. Quental and E.A. Ferrer, “Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived?” Nature 471, 2011, DOI: 10.1038/nature09678, pp. 51-57.

Calvillo, Nerea. “Political airs: From monitoring to attuned sensing pollution.” Social Studies of Science, Vol. 48 Issue 3, Sage Journals, 2018, DOI: 10.1177/0306312718784656.

Connor, Steven. The Matter of Air: Science and Art of the Ethereal. Reaktion Books, Chicago, 2010.

Demos, T. J. “Amy Balkin: (In)visible Matter.” International New Media Gallery Catalogue, edited by Edwin Coomasaru and Tom Snow, New Westminster, 2013.

Haskell, David George. “On the aromas of the first and last forests.” To Burn, Forest, Fire instruction booklet, IHME Helsinki for the World Weather Network, Helsinki, 2021.

Neimanis, Astrida and Verlie, Blanche. “Breathing Climate Crises: feminist environmental humanities and more-than-human witnessing.” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2023, Taylor & Francis Online, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0969725X.2023.2233810.

Paterson Katie, Siobhan Maguire, J. Sakari Salonen. and Zalasiewicz. “Art meets geology.” To Burn, Forest, Fire, to-burn-forest-fire.com, https://to-burn-forest-fire.com/. Accessed 16 March 2024.

Paterson, Katie. To Burn, Forest, Fire Instruction Booklet, IHME Helsinki for the World Weather Network, Helsinki, 2021.

Randerson, Janine. Weather as Medium: Toward a Meteorological Art. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2018.

Schuppli, Susan. Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2020.

Sloterdijk, Peter. Terror from the Air. Translated by Amy Patton and Steve Corcoran. Semiotext(e), Los Angeles, CA, 2009.

Visvanathan, Mallika. “Weathering Crisis: On 28° North and Parallel Weathers.” ASAP | art: alternative south asia photography art, https://asapconnect.in/post/696/singleevents/weather-ing-crisis. Accessed 15 March 2024.

Essays

Monsoon Equinox

It is the start of the year 2050. The months have melted away and the seasons seep into one another, liquid, languid. Time’s passage is guided solely by the cycles of the sun and moon, the Gregorian days of waged time a blurry memory of a past long gone. Back in the Old World, people learnt to manipulate time with the mechanics of manmade devices. They made clocks that could shift time back and forth with the turn of temperate seasons. An hour more to the working day, even as the daylight hours shortened; one less hour of sleep, even as the nights grew longer.

Here on the equator in the historied Riau-Lingga Archipelago, where the present-day Singapore state sits, time has always been consistent. Day and night will again remain at equilibrium in the year 2050, especially during the Monsoon Equinox when the Earth’s rotation is at zero degrees both latitudinally and longitudinally. The days will start at seven when the sun rises, and nights will start at seven again when the moon ascends. The only period in history when equatorial time was out of joint was when the ones who came from the Old World occupied these lands, and the tumultuous years after their exit, when the then-newly formed equatorial nation states grappled with the aftermath of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), another Old World mechanism that used the longitudinal Prime Meridian at 51° 28’ 38’’ N as the false ground zero of all-world time. Up until 1984, the position of Greenwich north of the equator was treated as the centre to which all other places on Earth had to coordinate their time. When rulership over the archipelagos and highlands running along the equator got scrambled up by conquest, there remained a period of confusion even after the occupying forces left, despite the revolutionary fervour of decolonisation, as to how to align time to the false centre of Greenwich. As an example, until 1941, Malayan Time was standardised with the Straits Settlements across all its lands and waters, to GMT +07:30. After the Malayan Federation split, there was more confusion to come, as Malaysia shifted its Old World-inherited clocks forward to +08:00 in 1981, and its ex-Federation counterpart Singapore chose to follow suit to match, for the sake of retaining business and travel relations across its new divisions.

Now, time is the same everywhere, cycling through the seven seasons all across the world. Many expect that at this year’s Conference of the Parties (COP) during the season of White Dew, it will be announced that the net-zero targets for carbon emissions, as set out in the Paris Agreement in 2015, have miraculously been met.

STEVE (Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement) and the Milky Way at Childs Lake, Manitoba, Canada, 2018. The picture is a

composite of 11 images stitched together. Photo by Krista Tinder, courtesy of NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre/Flickr.

Yet too much damage has already been wrought, and some changes remain irreversible, like the disappearance of the season named winter. Now, even at the poles of the Earth, a new year starts when the monsoon surges cause widespread, continuous, moderate to heavy rain, at times with 25–35km/h winds in the first half of the season, and rapid development of afternoon and early evening showers. There are no more glaciers or sea ice left on the Earth’s surface, only in the relics of deep freezers. As the last ancient ice sheet melted away in 2049, the polar vortex no longer remains polar, inciting a combination of warming air and ocean temperatures from the poles to the equator, and frequent occurrences of geomagnetic storms along the equatorial belt. Boreas (north wind) and Auster (south wind) are also no longer, having slowly been absorbed into the monsoon drifts of the equator since 2016, when the Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement (STEVE) phenomenon was first officially discovered. Instead of the Auroras Borealis and Australis, namesakes of the Grecian north and south winds, STEVE has been erupting across the sky every night during the Monsoon Equinox, a hazy enchantment of magenta amid the constant rain and warm winds of the season, a phenomenon which we can expect to continue seeing in 2050 as well. After the Monsoon Equinox, comes the season of Lalang Fires.1 Fierce winds are expected to plough through again this Lalang Fire season, when the warm monsoon winds turn dry and unpredictable, sparking grass fires across the island. It starts with the slow crepitation from burning weeds, with sound travelling fast towards the city centre. As always, it will be a busy season full of mayhem for the local Civil Defence Force, but they have maintained a strong track record of being reliable first responders to crises of varying natures since 1948, when a record-breaking heatwave sparked twenty-two fires across just four days. Investigations found that the cause of the outbreaks were unattended joss sticks at cemeteries during the Qingming Festival, a Taoist day of offerings to the spirits of deceased ancestors which historically took place 106 days after the Winter Solstice. Since the early 2010s, after the enactment of the New Burial Policy in 1998 that cited land scarcity as a reason to impose a fifteen-year term on burial grounds, Qingming rites began to migrate to temple columbariums as the dead were exhumed from the ground, and cremated or reinterred into crypts instead, depending on one’s religious beliefs. In 2007, the Crypt Burial System was introduced alongside the New Burial Policy, which saw the mass transference of Muslim places of rest to a grid-like cemetery in Choa Chu Kang, and the gradual disappearance of multifaith burial sites.

These days, Qingming is observed throughout the season, but temple managements have banned unattended fires in rites and rituals. They have also reduced the number of joss sticks that can be used for prayer (Ng, 2023). The institutionalisation of such practices has not meant their acceptance from devotees. The Force responded quickly and effectively to the 1948 fires, though, and have continued to do so since. Although Qingming-related grassfire outbreaks have dwindled over the years, it is predicted that the 2050 season of the Lalang Fires will not be any easier to manage than previous years, as dry winds blow across the island wilder than ever, at high speeds. For better or for worse, it has been remarked that “‘crisis’ is the metier of the Singaporean state.”2 Crisis conjures chaos, unmanageable and unruly. Crisis invokes control, as in damage control, a calculated managerial impulse enforced en masse. Chaos evokes anarchy, as in calls to action, the emergence of self-organised methods of living together in a more-than-human world. These first fifty years of the Anthropocene have oscillated wildly between crisis and chaos, a long, difficult balancing act between impulses to control, and grassroots organisational movements.

After the Lalang Fires comes the Awakening of Insects. The lingering heat of the grassfires warms the soil; the Earth becomes humid as hot air rises from the heated ground. Meanwhile, the hot humid air from the north is strong and creates frequent winds. Arising as a countermovement to the preventative measures against the grassfires, the Awakening of Insects has become a season of vernacular, syncretic ceremonies, when bonfires are lit in open fields to collectively mourn the losses of the last fifty years, while awakening new cycles of life. Unlike during the season of Lalang Fires, though the winds fan the flames of the ceremonial bonfires that are held during this season to rouse the insects from their slumber, humidity swallows the fires again by nightfall, and no major damage is expected.

As the earth warms, various species of insects, non-human and post-human, awaken from hibernation and rise from the soil. They swarm the skies, unhindered by the skyscrapers that used to dominate the Singapore horizon.

Image of a swarm of insects over an open field, created with Open AI DALL-E 3 text-to-image generation software.

Courtesy the author.

In murmurations numbering in the thousands, they begin their migratory journeys across the world, scattering lifegiving pollen and seeds along the way. Across the climate discourse that has developed since the start of the twenty-first century, some words often appear as suffixes: crisis and control, alongside others like action, adaptation, displacement, justice, migration, mitigation, reparations. These climate-related syntaxes generated a paradox of concurrent yet unsynchronised scenarios, where the consequences of centuries of anthropogenic climate change created extreme inequity throughout the world. Small islands in warming and rising seas were the first to initiate a global call to action, yet many of them were the first to suffer the consequences. The Paris Agreement has been fulfilled, but not without sacrifices and losses.

The Awakening of Insects is a time for mourning, while looking ahead. Many believe that the government’s 30 by 30 initiative, which aimed to achieve 30% of local food growth by 2030, failed because of their lack of support to preserve local and indigenous fishing and foraging techniques. Instead, an expensive, techno-engineering development programme was pursued with the singular goal of increasing agri- and aquacultural yields. In the process, open-air, land-based farms and open-sea fishing were forcibly replacing with confined, microclimatic solutions.

The word ‘microclimate’ implies the ability to control or manipulate ‘climate’ into something scalable and manageable, which has been proven to be an impossible task, though not for a lack of trying especially in the case of Singapore. Entrenched as it is in a long history of protectionism and safeguarding national interest, this logic of control fits neatly into its founding narrative of survival, that propagated the creation myth of the formation of the modern nation state. Early efforts to terraform the island’s natural landscape into a microclimate optimised for maximum productivity evidence this survival-of-the-fittest mindset. The narrative of climate control continued for a long time to undergird the development of the island-state as an ongoing project of constant monitoring, upgrading, and optimisation in the interest of microclimatic survival and flourishing.

But it was the park’s microclimate that he was most concerned about. Unceremoniously taking leave of the parks’ officials, he and Mrs Lee took an unscheduled walk along the Esplanade, with security officers and reporters hovering. Walking through the Anderson Bridge tunnel and past Victoria Theatre, they stopped by the Singapore River, near the statue of Stamford Raffles. There, the prime minister gave reporters his verdict. The pavement was so broad, he said, that the trees, even when fully grown, would leave large areas exposed to the sun. He noted that although the sun had nearly set, one could feel the heat through the soles of one’s shoes. He squatted suddenly and placed a palm inches off the ground. He could sense the heat radiating from the pavement, he said.

—Cherian George

Air-Conditioned Nation: Revisited, 20203

“Think of Singapore instead as the Air-Conditioned Nation,” the media scholar Cherian George once suggested, “a society with a unique blend of comfort and central control, where people have mastered their environment, but at the cost of individual autonomy, and at the risk of unsustainability.”4 And indeed, the time of unsustainability arrived, climaxing in the 2030s, heralded by the mass teardown of towering office and housing complexes as they turned from novel urban planning solutions to solve land scarcity, into safety hazards, as natural barriers of protection against strong winds slowly eroded away.

Tall, towering buildings, constructed with modernist materials like steel, glass, concrete and so on, became too heavy to withstand the relentless storms that come with Grain Rain, the season that follows the Awakening of Insects. As the ice sheets melted, sea levels continued to rise, and skyscrapers got torn down block by block in desperate efforts to keep reclaimed lands afloat. Their mass and centre of gravity were too high for the artificial islands on which they were built to remain buoyant amidst the floods that rushed in against the old water-breakers and sea walls. These historic fixtures have been around since the early 1990s, when the government first started mandating that every new reclamation and construction project had to be built to double the height of the expected sea level rise in annual Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates, and vulnerable highways constantly elevated. As more and more stone and cement were added to meet these standards, they started to weigh heavier and heavier on already sinking islands. By the late 2010s, 70% to 80% of Singapore’s coast, both natural and reclaimed, was already lined with hard walls or gradated stone embankments,5 but they could never keep up with the ever-increasing heights of new construction projects.

Inevitably, some islands sank, but for the most part, people have learnt to live with the rising seas. Bamboo rafts have become popular again, for their durability and tensile strength against the strong winds and currents that come with Grain Rain season. Historically celebrated by fishing villages in the coastal areas, Grain Rain marks the start of the fisherfolks’ first voyage of the year. On the first day of the season, marked by the first downpour since the Monsoon Equinox, people would worship the sea and stage sacrifice rites. The custom dates back thousands of years ago when people believed they owed a good harvest to the gods, who protected them from the stormy seas. This period of rainfall is also extremely important for the growth of crops. As the old saying goes, “rain brings up the growth of hundreds of grains.” It’s warmer than ever, but we are coping. There are less office buildings than there were before, as air-conditioning technology for hundreds of floors of square footage became too costly to bear, not with the net-zero target that had to be met.

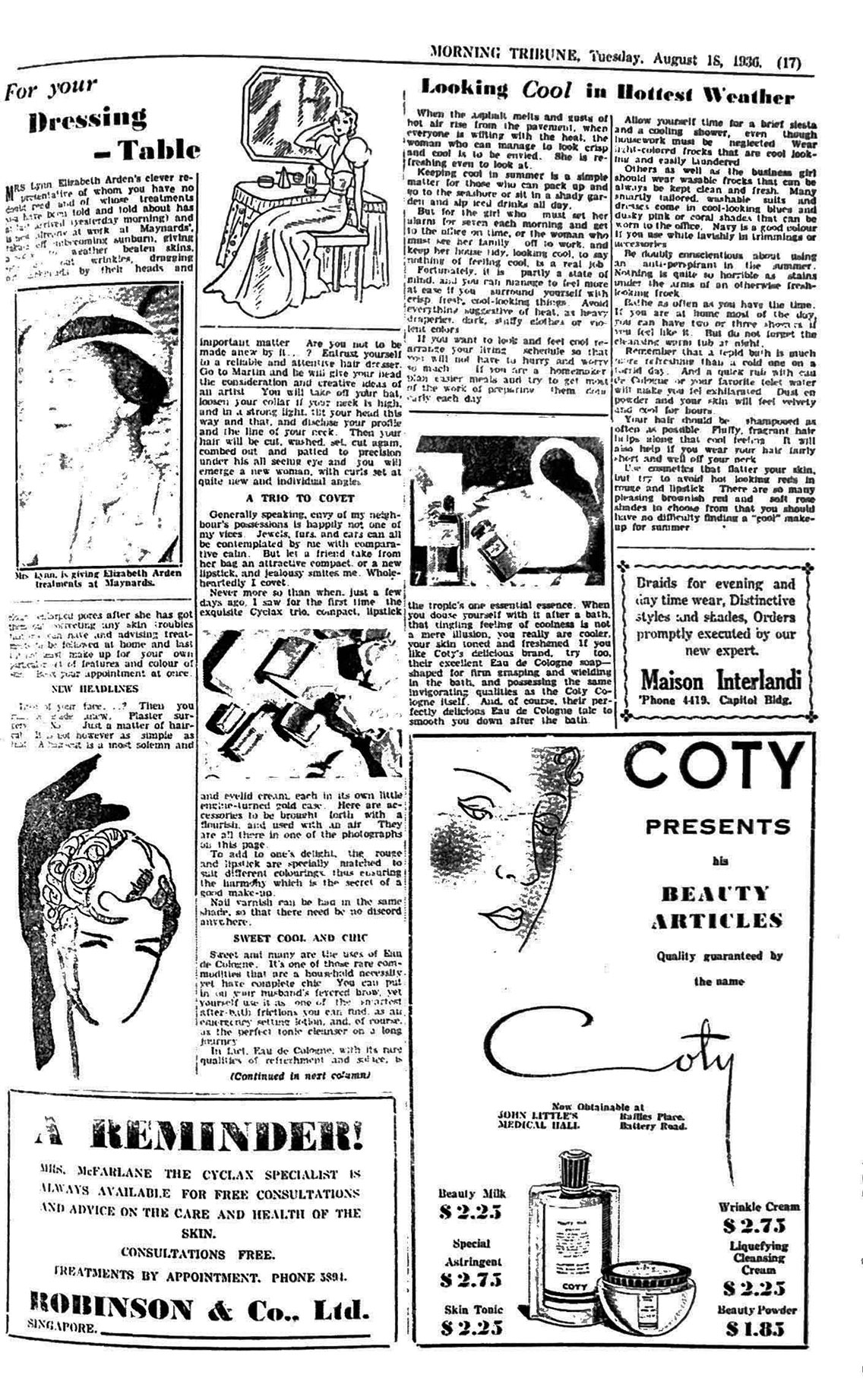

As the soil absorbs the rainfall of Grain Rain season, the earth warms again with the season of Rising Heat. During this season, the mid-afternoon heat is expected to reach an average maximum of 38 degrees Celsius, which meteorologists hope will be the limit for the next fifty years. Lazy natives, some were called by neocolonial leaders who had adopted or been indoctrinated by Greenwich Mean Time, for seeking shade under generous banyans in the mid-afternoon heat.6 Even then, the elemental forces of the equator proved powerful resistors to the clockwork rhythm of manmade time. When the red-haired ones first landed here, they too could not deal with the heat, and perhaps never learnt to do so. A piece of advice in the Malayan Federation’s local daily Morning Tribune read in 1936, more than a hundred years after their first landing, “If you want to look and feel cool, rearrange your living schedule so that you will not have to hurry and worry so much … Allow yourself time for a brief siesta and a cooling shower …”7

The ‘living schedule’ on the equator (though not quite about a cool, leisurely, and worry-free life), however, was always already in tune with the eddying movements of heat, governed by the cycles of the sun and moon. Workers of the land would rise with the sun while taking breaks in the shade, while fisherfolk who work on floating farms would follow the push and pull of tides, as the moon waxes and wanes. They work this way not out of laziness or indolence, but because they know it makes no sense to work against the weather, or on a time out of joint.

Across the 2010s and early 2020s, construction companies learnt this the hard way when they started losing workers to heat-related accidents, despite groups like the SG Climate Rally (SGCR) warning and advocating heavily against such workers’ violations. Construction entities have since dwindled in influence or transformed into unionised coalitions. The construction boom in Singapore infamously started in 1961, following the notorious Bukit Ho Swee fire that skyrocketed the profile of the then-nascent Housing Developing Board (HDB). The fire, which broke out in the tightly packed and highly flammable kampong squatter settlement of wooden houses in Bukit Ho Swee, rendered some 16,000 people homeless, despite a robust ‘culture of fire’ that existed in kampong settlements, in which local volunteer firefighting squads consisting of unemployed youth and secret society members took turns to patrol the kampongs. The biggest fire yet in Singapore history, outdoing even the 1948 grassfires, it is considered by many as the pivotal moment in the transformation Singapore’s architectural and social landscape, turning unruly urban squalor and ‘inert’ squatter communities into modern, lawful citizens living in planned estates.8

“Looking Cool in Hottest Weather.” The Morning Tribune, 18 August 1936, p.17.

Courtesy National Library Board, Singapore. First cited in an essay by Fiona

Williamson in the chapter “Lalang Fires” in The 2050 Weather Almanac,

ed. Soh Kay Min and Ng Mei Jia, 2024.

Till this day, the cause of the conflagration remains a mystery, though there were whispers during the heated pre-independence years of the early 1960s, that the Bukit Ho Swee fire was a case of arson, sparked by the then-ruling party to declare a state of emergency that would blaze a path straight through the kampongs, so to speak, and clear space to launch their highly-anticipated high-rise public housing model. These rumours were never verified but reveal an enduring fact of public perception and the power of grassroot beliefs. Even as the heat of fire dissipates, the smoke of secrets lingers in the air long after. This season of Rising Heat, the case of the Bukit Ho Swee fire is tabled to be reopened for investigation, as civil society calls for accountability for the numerous heat-related deaths on construction sites force the courts to locate and address the historical root of the problem.

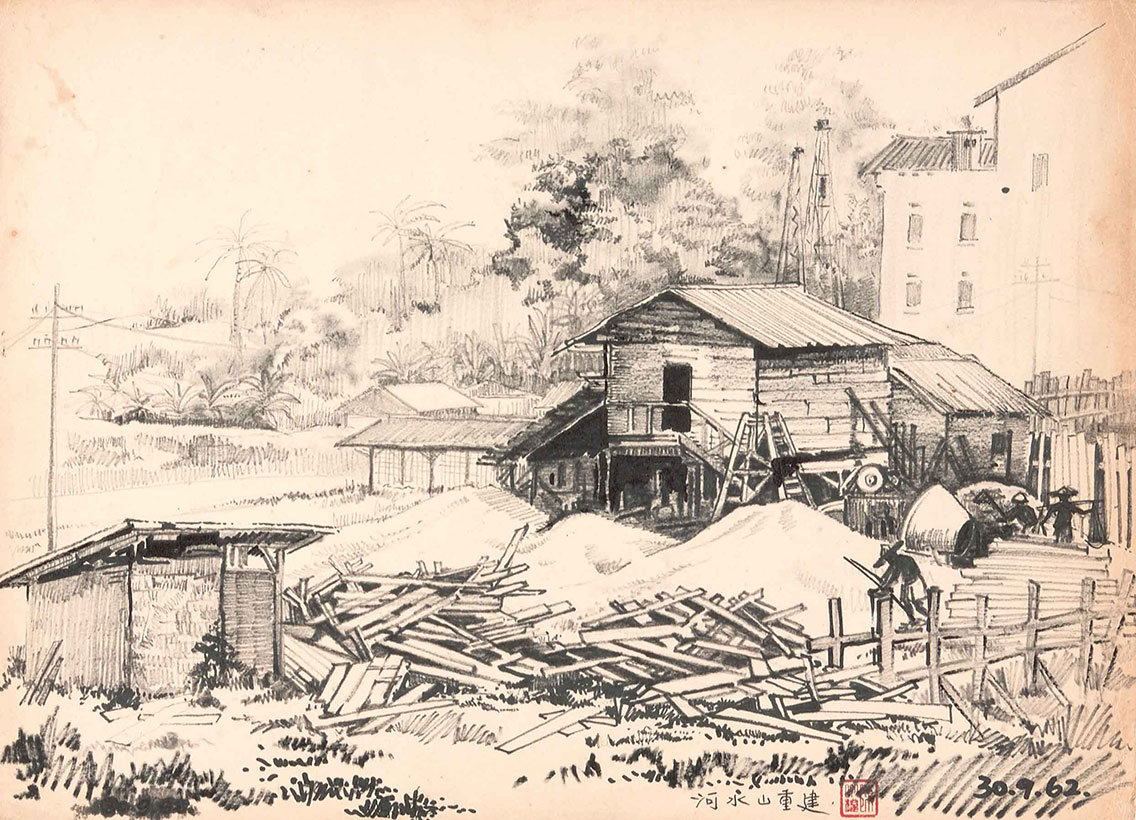

Tan Choo Kuan, Rebuilding Bukit Ho Swee, 1962.

Ink on paper, 37.3 x 27.2 cm. Gift of Ms Tan Teng Teng. Collection of National

Gallery Singapore. Courtesy of National Heritage Board, Singapore

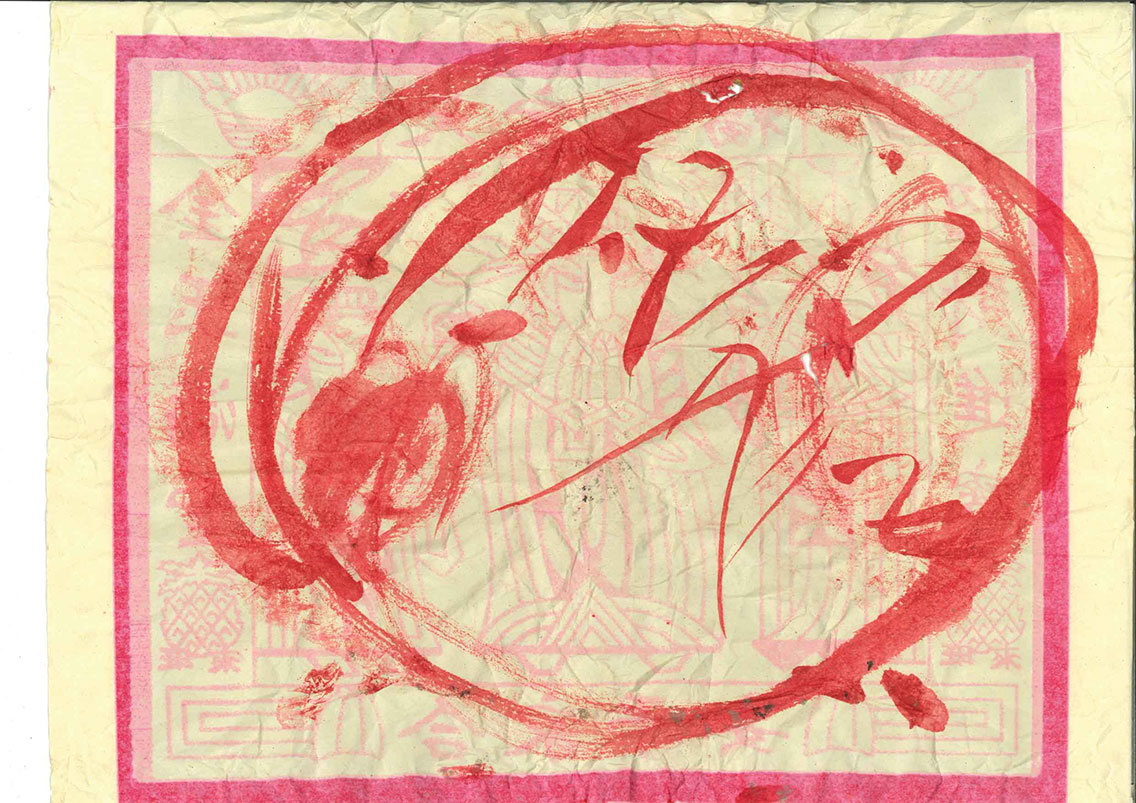

Ink drawing on joss paper by Thunder Marshall Leizhenzi, during a consultation

at Shui Gou Guan Temple, Singapore, on 27 November, 2023.

Courtesy of Shui Gou Guan Temple.

Bolts of lightning illuminate the sky in the season of Sumatra Squalls, as hot afternoons get subsumed by sudden thunderstorms and short-duration showers, and strong wind gusts up to 40–80km/h stir up the seas from the predawn hours until midday. Taoist devotees have long believed that the Thunder Marshall is most active during this season. A leading deity of Heaven’s Department of Thunder, he descends to the mortal realm every two weeks during this season, to commune and provide consul with his congregation, channelling his presence through spirit mediums and ritual performances. The Thunder Marshall’s likeness is said to be that of a bird, and the howling squalls of the season’s early morning wind gusts are believed to be a sign heralding his arrival, alongside booms of thunder that rumble like a drumbeat through the air and in one’s chest. Legend has it that at the bidding of the Heavens, he metes out punishment to both earthly mortals guilty of secret crimes, and evil spirits who have used their knowledge of Taoism to cause harm in the realm of Earth.

Yet the power of the deities resides in the power of belief in their presence. It is based on a dialectical relationship between the spirit and mortal realms. Within the last fifty years, the mortal realm has encountered an unprecedented series of ecological trials, as fires during the hot seasons took away lives and destroyed infrastructure, or lack of rainfall during Grain Rain in some years resulted in poor harvests and hungry ghosts. Belief in the gods waxed and waned, as people wondered if their prayers were being heard at all. As a rare interview with the Thunder Marshall conducted in 2023 showed, however, the deities do not hold any material sway over events of the mortal realm, neither are they capable of controlling the weather.9 Rather, they exist with the cycles of nature as it transforms: the two seasons of fire, Lalang Fires and the Awakening of Insects, used to be one. But as the Thunder Department saw the sincere, continuing need of the people to mourn with open fires, even as temple managements banned the practice, Madame Wind, another deity of the department and a trusted assistant of the Thunder Marshall, turned the dry gusts wet and humid, tamping out the bonfires that would otherwise spread through the island.

Historically, years began with the Winter Solstice. It was the first solar term to emerge in the traditional lunisolar calendar. As the months melted away and winter disappeared, White Dew has become the last season of the year. As the squalls die down and storms abate, an unusual chilly vortex is left to signal the last of the seven seasons. When air-conditioning was still a widely utilised tool of climate control and heat relief, meteorologists struggled to forecast the season of White Dew as its namesake dewy residue, a result of vapours condensing on grass and trees, were spotted all the time instead of just during the morning hours. Since the mass teardown of high-rise buildings lined with vertical columns of air-conditioning units for each household, it has been much easier to recognise the arrival of White Dew.

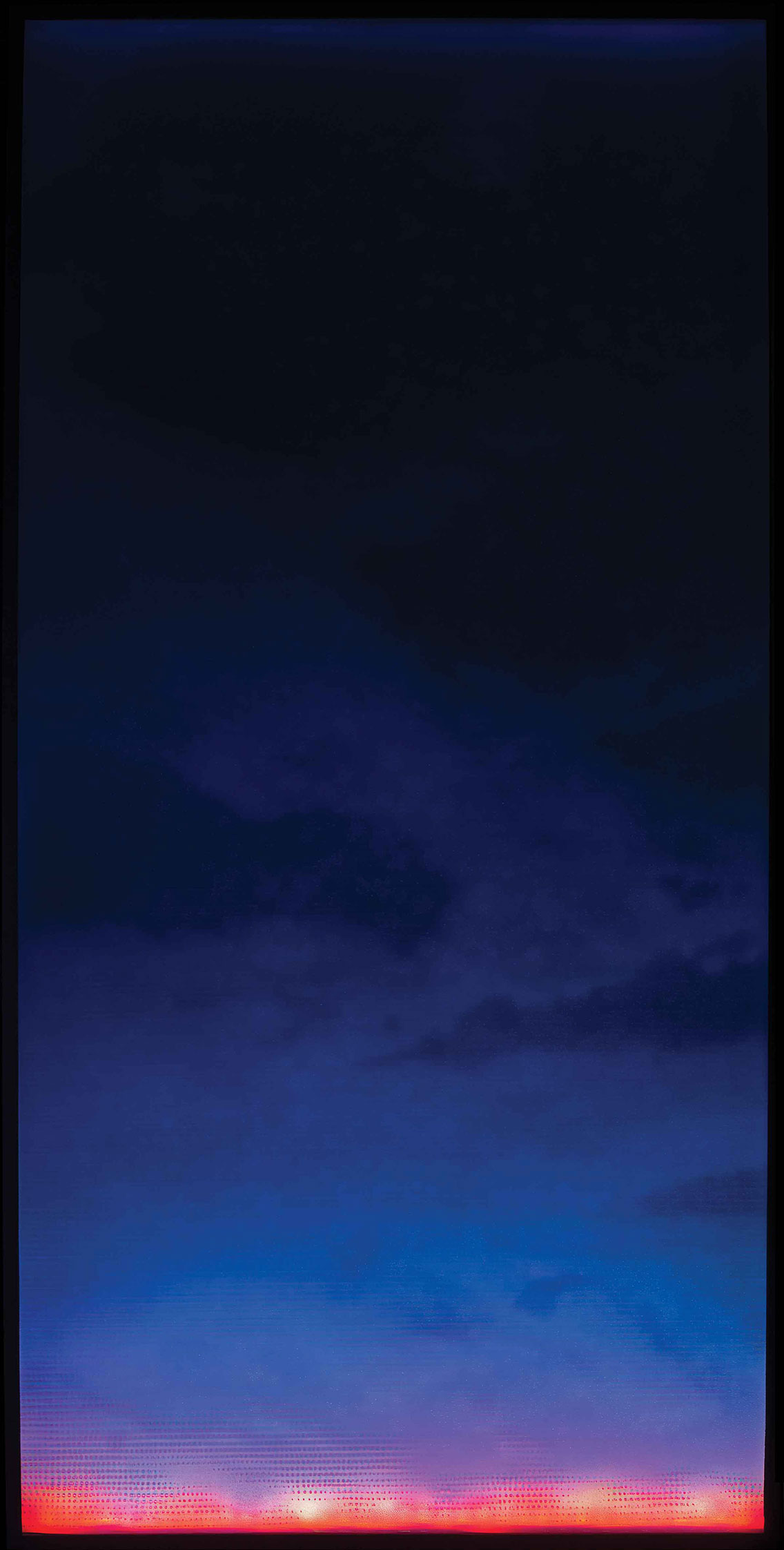

There was a period when the invention of the air-conditioner was seen as a life-changing technology that changed the lives of people in the tropical regions. This was the time in between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, when the ‘lazy native’ myth had yet to die away. A fabled leader of the time once said, “before air-con, mental concentration and with it the quality of work deteriorated as the day got hotter and more humid... Historically advanced civilisations have flourished in the cooler climates. Now, lifestyles have become comparable to those in temperate zones and civilisation in the tropical zones need no longer lag behind.”10 In the year 2050, however, the coldest season has been lost, and some like the artist Kent Chan (in his videos Future Tropics, 2023; Warm Fronts, 2022; Monsoon Sessions, 2022) even anticipate a complete mono-climatic expansion in the next few hundred years, in which all meridians and parallels will become tropical. This White Dew is expected to be slightly warmer than the last, considering the melting of the last ice sheet in the past year. Along with the possibility of a New Tropics, this issue is expected to be a key point of discussion at the season’s annual Conference of the Parties.

Kent Chan, Future Tropics, 2023, video still. Courtesy the artist.

Acknowledgements

The research for this essay is supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 2 grant for the project Climate Crisis and Cultural Loss (MOE-T2EP40120-0002).

Footnotes

1 Lalang is a tall grass (Imperata cylindrica) with linear leaves that can grow up to 2m tall, found in tropical, sub-tropical and monsoonal climates.

2 Waldby 372.

3 George 17.

4 Ibid. 19.

5 Schneider-Mayerson 169.

6 Alatas.

7 “Looking Cool…” 17.

8 Loh 19.

9 Ng, “Introduction…”

10 George 18.

References

Alatas, Syed Hussein. The Myth of the Lazy Native: A Study of the Image of the Malays, Filipinos and Javanese from the 16th to the 20th Century and Its Function in the Ideology of Colonial Capitalism. Oxon, UK and New York, US: Frank Cass and Company Limited, 1977.

George, Cherian. Air-Conditioned Nation Revisited: Essays on Singapore Politics. Singapore: Ethos Books, 2020.

“Imperata cylindrica,” National Parks, 2023. www.nparks.gov.sg/florafaunaweb/flora/4/3/4325

Loh, Kah Seng. Squatters into Citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore. Singapore: NUS Press, 2013.

“Looking Cool in Hottest Weather.” The Morning Tribune, 18 August 1936, p.17. First cited in an essay by Fiona Williamson in the chapter “Lalang Fires” in The 2050 Weather Almanac, ed. Soh Kay Min and Ng Mei Jia, 2024.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre/Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/26938621338/in/album-72157693734878994/)

Ng, Mei Jia. Introduction to “In conversation with a deity: how’s the weather lately?” The 2050 Weather Almanac, ed. Soh Kay Min and Ng Mei Jia, 2024.

Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew. “Some Islands will Rise: Singapore in the Anthropocene.” Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities, Vol. 4, No. 2–3, Spring–Fall 2017.

Waldby, Catherine. “Singapore Biopolis: Bare Life in the City State.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal, Vol. 3, 2009, Issue 2-3: Double Issue: Emergent Studies of Science and Technology in Southeast Asia.

Essays

Weather Report Australia

James Geurts—Weatherman

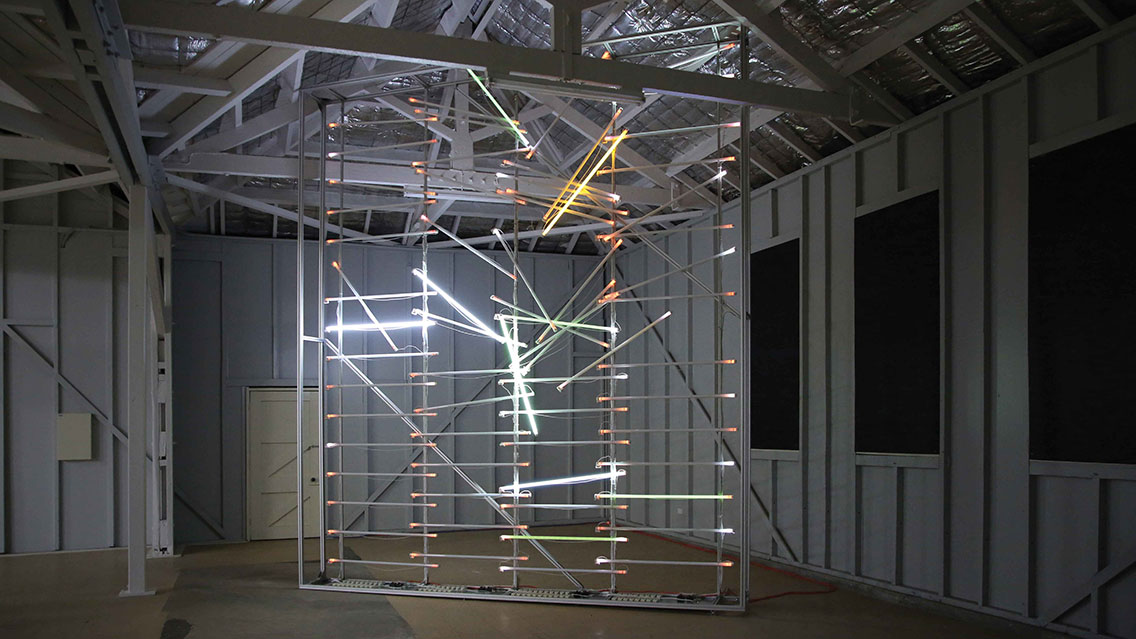

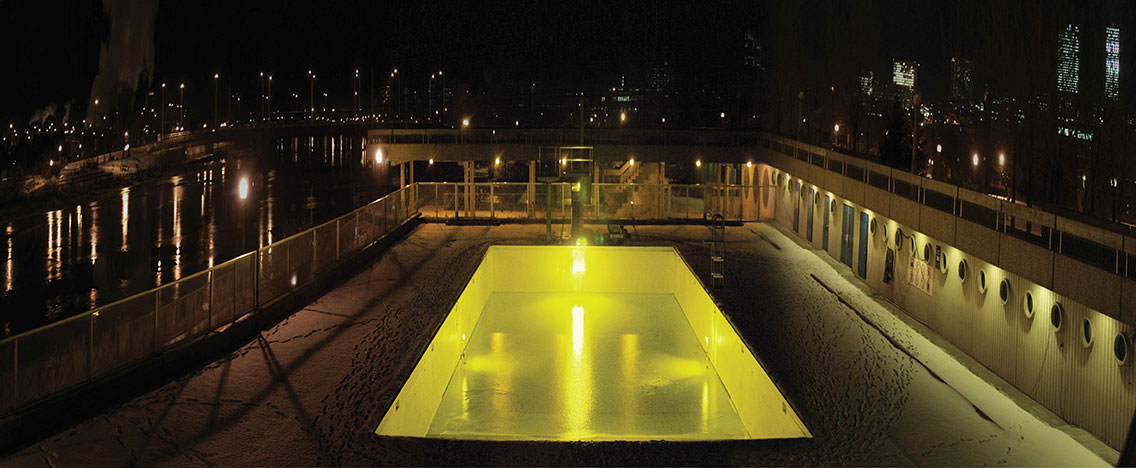

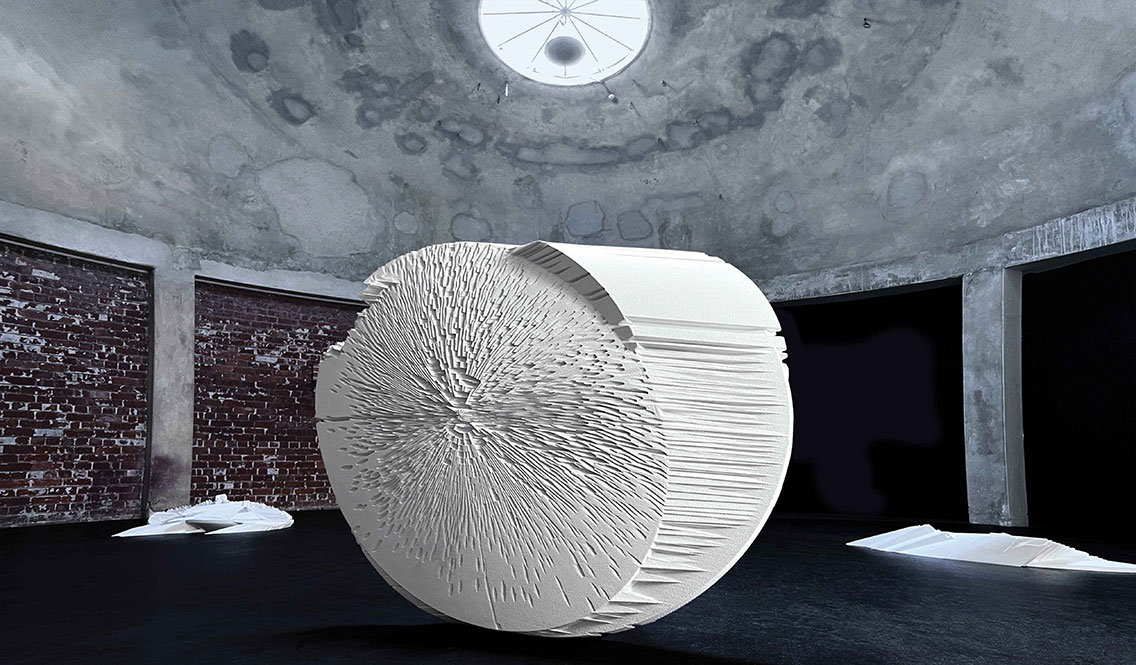

James Geurts performs many rituals, through which he tells many stories, involving water and journeying, incorporating them in temporary arrangements of light and 3D structures. These are accompanied by less ephemeral marks on man-made surfaces, notably drawings and photographic prints. Fluidity, or mutability, is his leitmotif.

—Dr Julie Louise Bacon, Edinburgh,

Beyond interpretation and judgement, writing the story of art.1

I’m sitting on a North Melbourne decking with artist James Geurts, discussing the many weather-related projects he’s undertaken over the past three decades. We’re in 37-degree heat, as Australia feels the full force of climate change. Bush fires burn out of control west of nearby Ballarat. He’s telling me about Standing Wave: Drawing Tide, a work he made at The Bay of Fundy in 2012, and exhibited at the Dalhousie Art Gallery in Halifax, Nova Scotia.