VOLUME

ISSUE 04

Island

The focus of the issue is islands. Providing an aesthetic, critical and philosophical reading of islands, this volume takes an interdisciplinary approach to postulate islandic imaginations and potentialities as cultural, political and environmental concerns outline their existence in a fast-morphing geo-political space.

ISSUE 04

2015

Island

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Essays

Exhibition

Conversations

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Re-marking Islands

Essays

All The Same But Different: Between Islands

Another Island Poem

Exhibition

The Islands View

Conversations

Sand Man Charles Lim in Conversation with Foo Say Juan

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy-Editor

Lisa Cheong

Editorial Advisor

Milenko Prvački, Senior Fellow

LASALLE College of the Arts

Manager

Layna Ajera

Contributors

Biljana Ciric

Wulan Dirgantoro

Ho Tzu Nyen

Antti Laitinen

Raimundas Malašauskas

Nicholas Mangan

Aubrey Mellor

Charles Merewether

Shabbir Hussain Mustafa

Dev N. Pathak

Shubigi Rao

Anca Rujoiu

Tan Huamu

Introduction

Introduction: Re-marking Islands

Humans can live on an island only by forgetting what an island represents…

Dreaming of islands – whether with joy or in fear, it doesn’t matter – is dreaming of pulling away, of being already separate, far from any continent, of being lost and alone – or it is dreaming of starting from scratch, recreating, beginning anew. Some islands drifted away from the continent, but the island is also that toward which one drifts; other islands originated in the ocean, but the island is also the origin, radical and absolute.

Gilles Deleuze, Desert Islands and Other Texts, 2004

Issue 4 focuses on islands. Inviting artists, scholars, art historians and curators, this volume provides an approach to reading and meditating on islands, thereby contributing to emerging discourse on islands as a subject of inquiry and creative practice.

Islands are nature’s debris and as Jacques Derrida remarkably says, “there is no world. There are only islands.” (Derrida, 2011) Broken away from the whole since the beginning of human consciousness, islands have been creations of nature’s wrath. Yet with human evolution, the idea of a relationship to the concept of an island as an imaginary to articulate the human condition resides most poignantly in John Donne’s oft-quoted opening line of his poem “No man is an island.” Yet, at once, visualised often as a castaway, exotic, uninhibited, fearful, lonely, et cetera, an island is a potent compression of a country, a nation. Islands are imagined, visualised and romanticised in many ways but it is but an object and an objection in the vast seas. For example, while islands, such as Singapore and Hong Kong, remain ports of commerce, they are but negotiation sites for socio-cultural identities and transmigrational practices over the centuries; they do not represent the idyllic but rather a microcosmic world-making in the mirror of the great continents. The emerging contemporary island is a heterotopic space, and while integral and key to 21st century world-making, it is a site of geo-political determinism.

There is newfound energy in trying to contextualise island identities, cultures and contexts: island studies (Baldacchino 2007); nissology (McCall 1994); performative geographies (Fletcher, 2010) and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982) – all providing valuable insights to the place, presence and purpose of islands and their relationship to the adjacent, the historical, the sovereign and the political. But the agency of island cultures cannot be read merely through the lens of geo-political determinism or through the narratives of discovery or cultural representations. There are complex anthropocenic conditions of ownership (China’s claim over the Spratly Islands), war (ethnic wars in Sri Lanka), conservation (Madagascar’s palms verging towards extinction), and nature’s calamity (rising sea-levels could see Maldive islands disappear). Against this backdrop remains old 18th and 19th centuries concepts of being castaway or even exiled from civilisation, variably captured in literature and film, where the island remains the place to test human fortitude and deliver a philosophical exposition of the human condition.

Contemporary world re-fashions this condition of neglect, exile and the dark into an adventure for the urban individual. American television perpetuates this adventure through reality shows such as the long running machiavellist Survivor, hedonistic Temptation Island, Discovery channel’s docu-drama Naked and Afraid. They reinforce a notional belief that western society’s disconnect with itself and nature can be remedied through these enterprises which reveal nothing more than the dark side of human behaviour. Then, there is the romanticised notion of an island getaway, exalting solitude. With the flurry island holidays from Jamaica, Hawaii, Bali, Phuket, Fiji, Mauritius, et cetera, the lure of basking in the sun, sand and the sea remains a populist tourist adventure, reduced to vagabondic lifestyle of braided hairstyles, beach massages, water-sports and seafood, but impactless on the consciousness of lived experience - one that was seeking solitude in the first place.

Recent times have seen an increasing number of islands for sale, on Google, to the wealthy to build their own paradise. But can paradise be regained through real estate? I extrapolate this trend to provide us with a possible canvas for emerging trend in global land acquisition. In Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy (2014), sociologist Saskia Sassen eloquently raises the cruelty of the global economy. Foreign and domestic governments’ rapid investments to faciliate a ready supply of natural resources is displacing cottage economies, localised communities and nature. On one level, this could be read as a socialist cry for anti-capitalism yet, the subjected and subjugated are expelled from their natural habitat as the financialisation of the non-economic sectors of society takes root. She notes, “What is new and characteristic of our current era is the capacity of finance to develop enormously complex instruments that allow it to securitise the broadest-ever, historically speaking, range of entitites and processes” for “seemingly unlimited multiplier effects…To do this, finance needs to invade – that is to securitise – nonfinancial sectors to get the grist for its mill.” (9). Sassen’s reading, does not directly speak to islands. But they are the incubators for the further perpetration of countries, continents and economies. In this emerging trend, the inalienable gets alienated, and loneliness becomes the close companion of the island and its inhabitants.

If at all, alienation and loneliness remain critical to the understanding of the human condition on an island. Alienation and alienability prospects the loss of connectivity (often realised through bridges) and economic potential, dependence on natural resources for sustenance, existential challenges of nation-building and population sizing and balance. These continue to plague many island nations as they negotiate the probability that islands are more vulnerable for disappearance through political acquisition, wilful neglect of resources and economies and people uprooting and migrating. Loneliness besets.

The vast literature around loneliness and soltitude informs a human craving for consolidation – a life of the ascetic revisited. Often both are unfortunately conflated. Solitude purges the mind of clutter and searches for meanings whilst loneliness craves affect and searches for ways of meaning-making. There are not many islands that seek solitude but there are many that are lonely seeking to exert an identity and place themselves with a dialogue with the rest of the world. The dialogue is not necessarily convivial. It can also be adversarial. Loneliness can beget self-affection and interiority that develops a carapace against the belief that the world out there is harsh, cruel, total. Derrida’s reading of this in the Beast and Sovereign (2011) maps the possibility that loneliness and islands draw attention to the consideration that there is no such thing as a common world, a unified world. Loneliness can be ambiguous and Derrida considers the possibilty of the affected and the disaffected drawing closer in this loneliness to a common unity.

Perhaps, that is the fear, that one day the island will be alone. But the island as signifier propounds that it is not the central site but a signifier of the all things that it is not - that comes to interplay in the concept of being an island. The island differs by being unlike that continent, peninsula or hinterland adjacent to it, seeking to define its existence amidst a sea of trouble and possibilities. The island is that which is not. Its lack provides its strength. Its strength lies in its loss.

Philosopher Gilles Deleuze, known for bridging geography and philosophy in his seminal works with Félix Guattari, provides an ontological perspective. The island is the “origin, radical and absolute,” breaking away from essentialist doxa such as castigation and loneliness to a place where the incidental and adventurous come to play. Drawing from geographers, he articulates two kinds of islands: Continental islands which are accidental and derived and Oceanic islands which are originary and essential, both revealing “profound opposition between ocean and land” (Deleuze, 2004). Underlying this articulation is the inherent conceptual and existential divide that separates the real and harsh reality of being from a romantic notion of the idyllic. For Deleuze, these planes enmesh.

The constitutive qualities of the enmeshed planes form the basis of this volume of Issue. These essays, conversations and exhibition have been curated to re-mark the ‘island’ and provide an aesthetic, yet interdisciplinary, interrogation of the theme. Issue 4 speaks of the complex issues that I have raised above and it seeks to provide a rich palimpsest of unarticulated approaches to understanding the island as phenomenon.

References

Baldacchino, Godfrey (ed). A World of Islands: An Island Studies Reader. Prince Edward Island, Canada: Institute of Island Studies, 2007.

Derrida, Jacques. The Beast and the Sovereign, Volume II. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Deleuze, Gilles. Desert Islands and Other Texts: 1953-1974. Translated by Mike Taomina. MIT Press, Semiotext (e), 2004.

Fletcher, Lisa. ‘ “... some distance to go”: A Critical Survey of Island Studies’ in New Literatures Review. 2010. Vol. 47-48, pp. 17-34.

McCall, Grant. “Nissology: A Proposal for Consideration” in Journal of Pacific Society. 1994: Vol. 17, 2-3, pp. 1-14.

Sassen, Saskia. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Essays

The Island is I: A Brief Biography

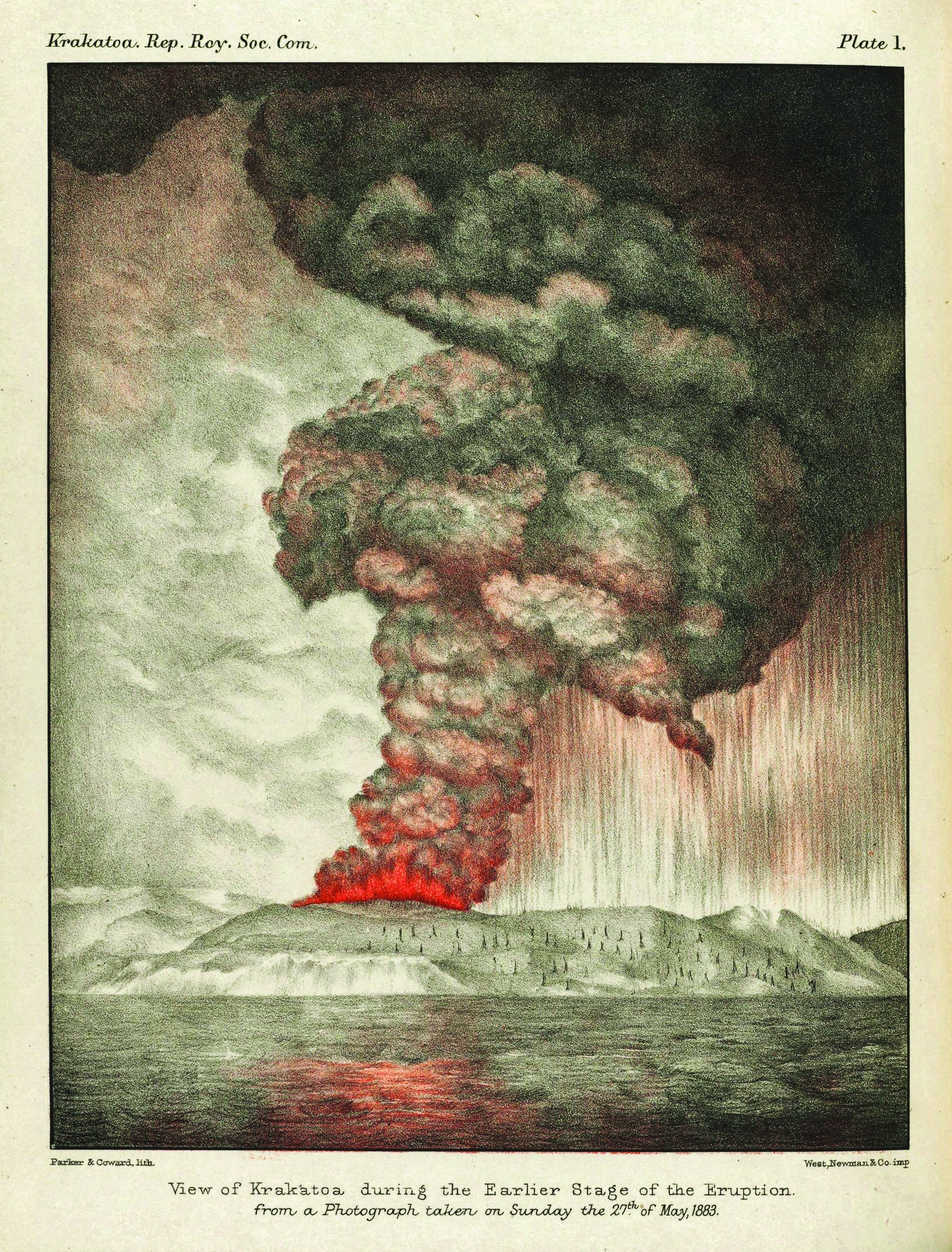

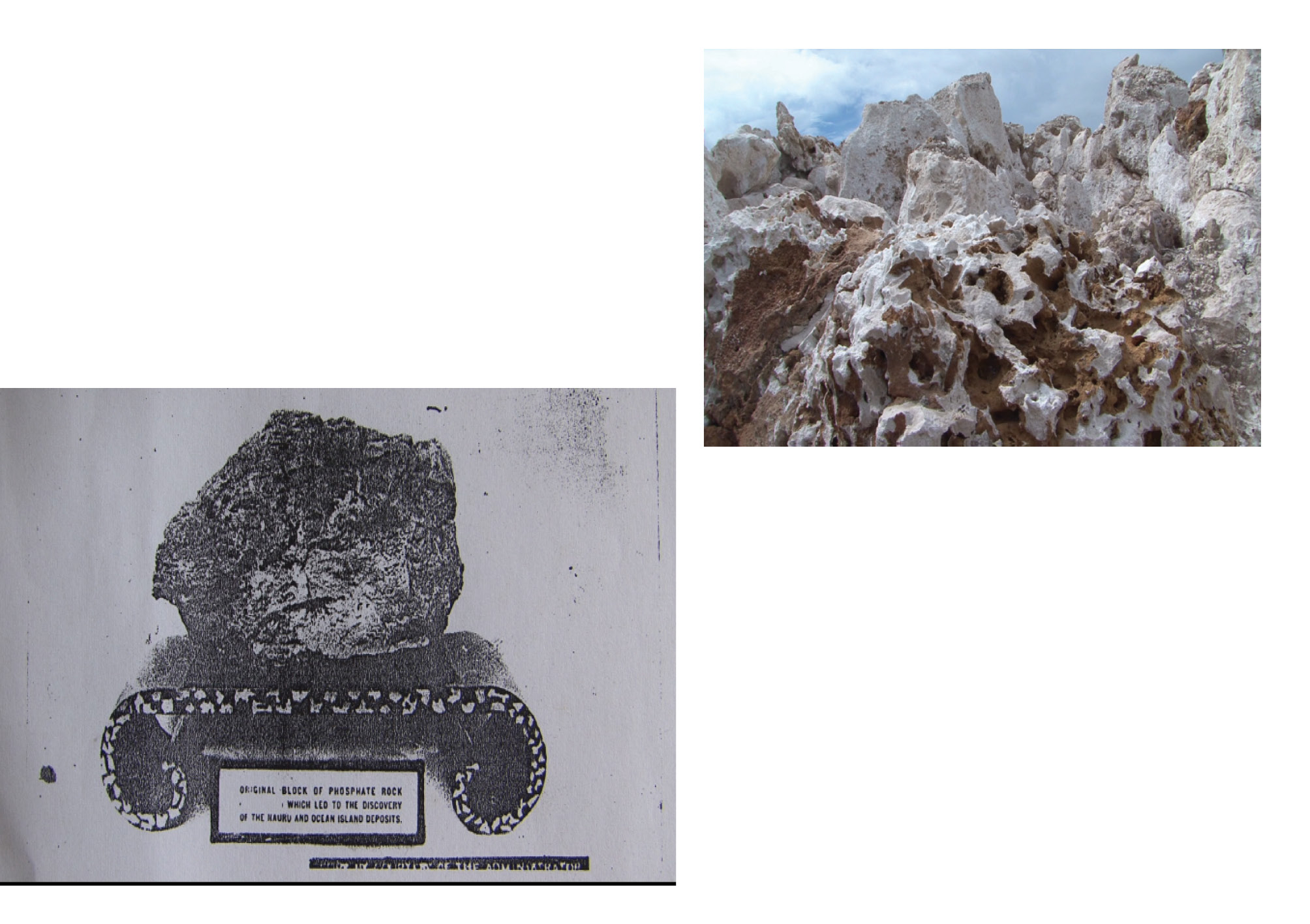

Royal Society et al. ‘The eruption of Krakatoa, and subsequent phenomena’.

Report of the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society.

London, Trübner & Co., 1888. Plate 1: Lithograph of 1883 eruption of Krakatoa.

The first island I remember hearing about as a child was of Krakatoa obliterated in 1883. Too young to fully comprehend the horrific loss of life, I was fascinated instead by the factoids that accompanied it. That the explosions were heard halfway around the world. That weather patterns were disrupted by clouds of dust, ash that orbited the globe, and that the shock waves circled the planet seven times. That spectacular sunsets were visible all around the Earth for a year, and in the British Isles, those sunsets would be captured by landscape painters. That the force of the final explosion (always measured in comparison to nuclear blasts) made an island disappear. And so my first island was not an island at all.

The second was Bikini Atoll. To my unformed child-brain, this was a human experiment made to imitate nature, like the helicopter and the dragonfly. I imagined radioactive clouds in colours of similar spectacular sunset, and wondered if particles still lazily circumnavigated the globe. I knew some had made landfall in India. But I was disappointed that no island had disappeared. At the very least there should have been a Santorini-like caldera. Unsurprisingly there was very little information about nuclear tests available to an inquisitive child living in India during the Cold War.

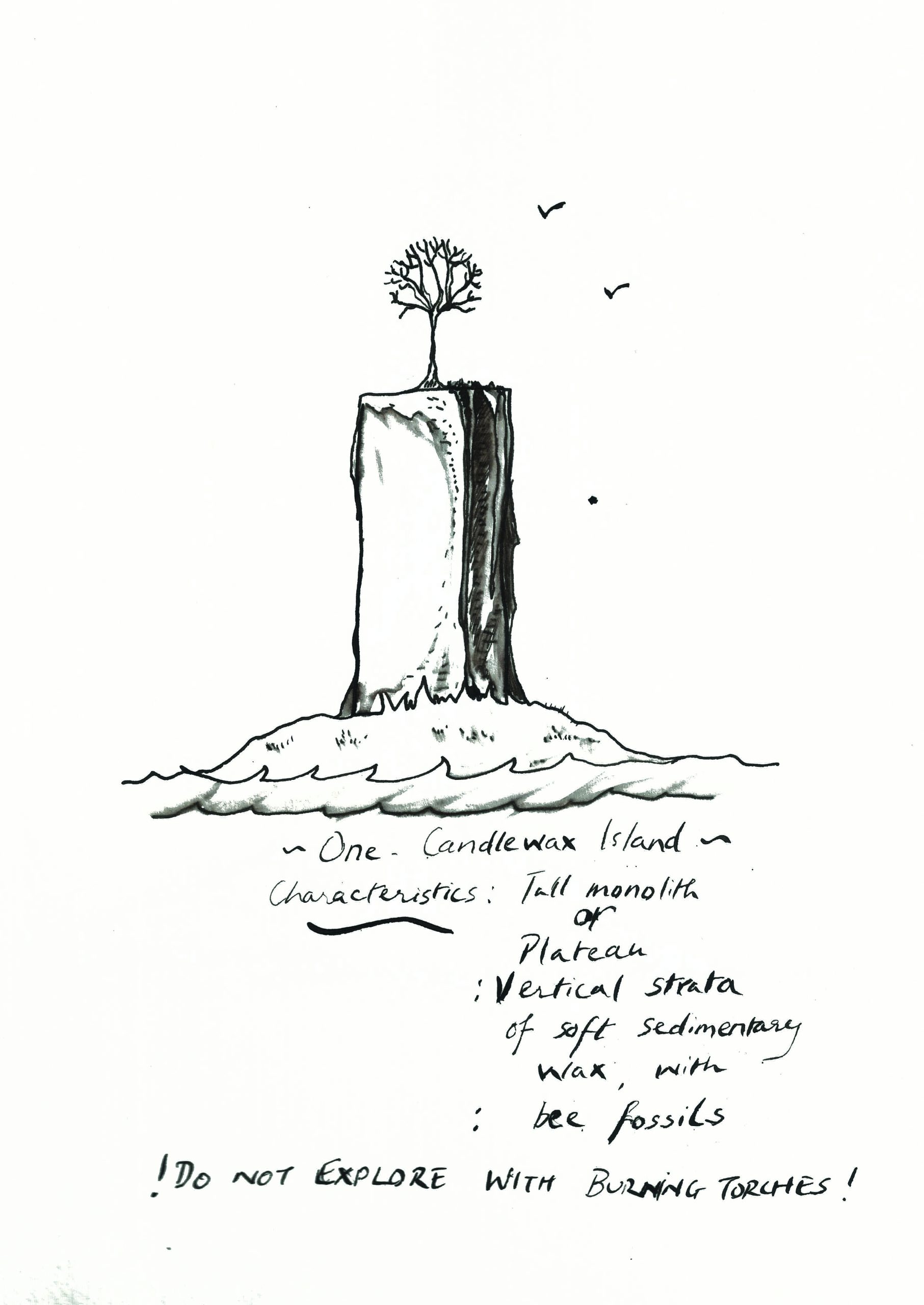

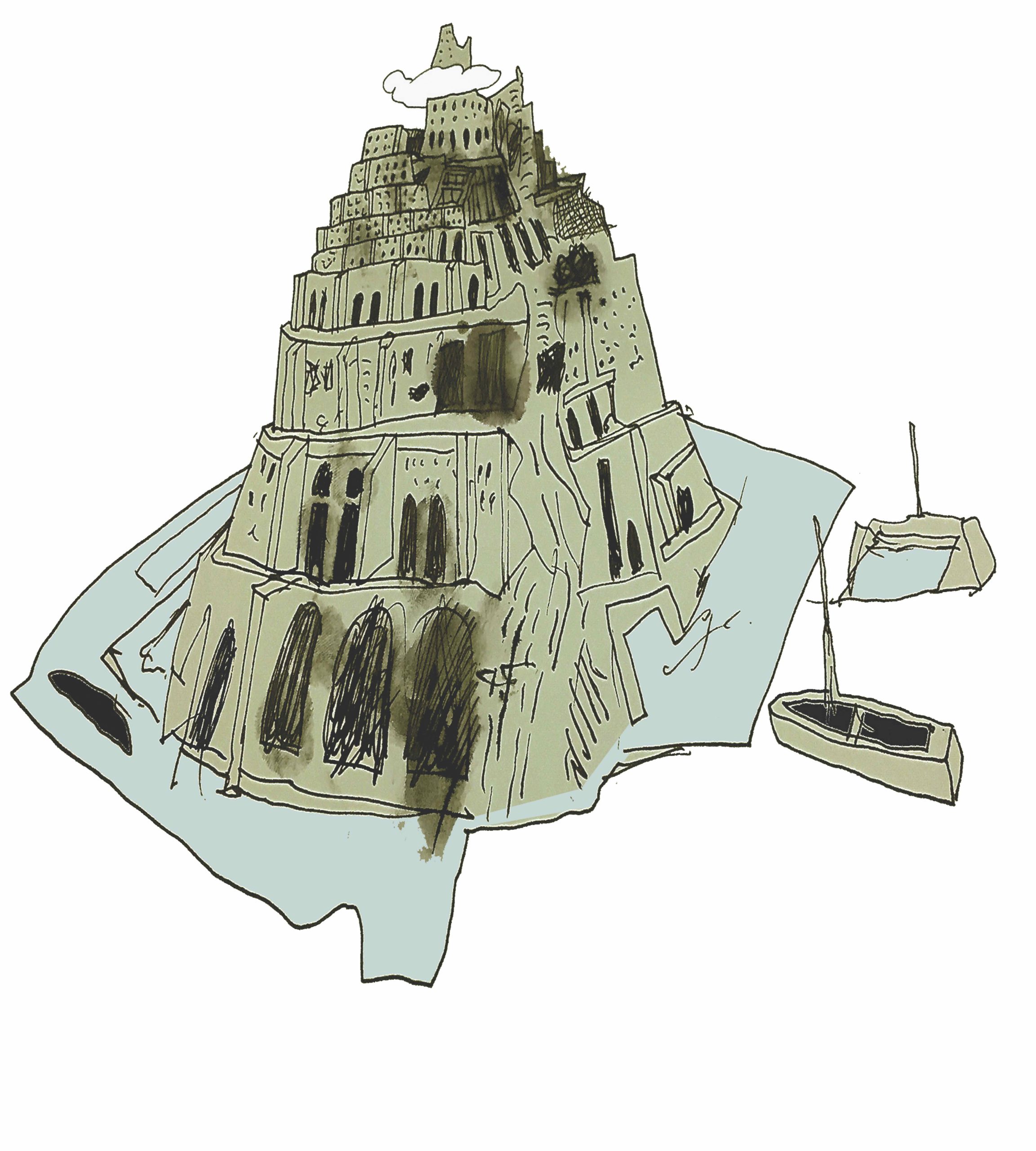

To redeem this deficiency, at 10 I wrote a little handbook for island explorers. Heavily influenced by my parents’ library of 17th -19th century naturalists and explorers, this was a manual for intrepid naturalists and discoverers, very much of the here-be-monsters genus. It contained a way to identify and classify islands, and not mistake them for continents, as Christopher Columbus did. I modelled my imagined islands after conventions of the genre of course, but also after walnut shells, spacecraft from Star Trek, funny hats and birds’ nests. The frontpiece though, was a trough-like depression of sunken nothingness, ringed by coral reefs that kept the sea out. This void-as-island was what I imagined the aftermath of an explosion to be.

From lost atolls, vanishing archipelagos, to mist-shrouded and obscure outcrops, the general instability and unknowability of islands has always been the stuff of books of adventure, to which I was also quite addicted as a juvenile. Insulated from the prosaic world outside, I spent my childhood happily marooned in my parents’ library. I already knew that only on islands would the likelihood of first discovery, of original encounter, of mapping the inconceivable be truly possible. Discovering a continent was to me not a revelation on par with the strange weirdness of islands like the West Indies, Galápagos, of the islands of the South Pacific. This silly guidebook was very much the awkward, faintly ludicrous imagining of a half-grown child, and is thankfully lost. But since I’m writing about it, exactly three decades later, here is a poor mnemonic reconstruction of a page.

Rao, Shubigi. Reconstructive drawing of lost handbook.

Medium: pen, ink and poor memory. 2015

And in the 30 years intervening between those first thoughts and this reconstructive scribble, this is what I think I know about the island:

The island is Singular, like the racialist ethnographic and anthropologic device employed when speculating upon the unfamiliar and unknown. It is the reduction of disorder and divergence to a solitary specific as representation of the native, the observed, the other. It is singular too, in its stubborn peculiarity, in how no one island is like another, or like anywhere else. It shares this conceit with every human ego, and so, being us but at the periphery, perhaps the Island is also the Id.

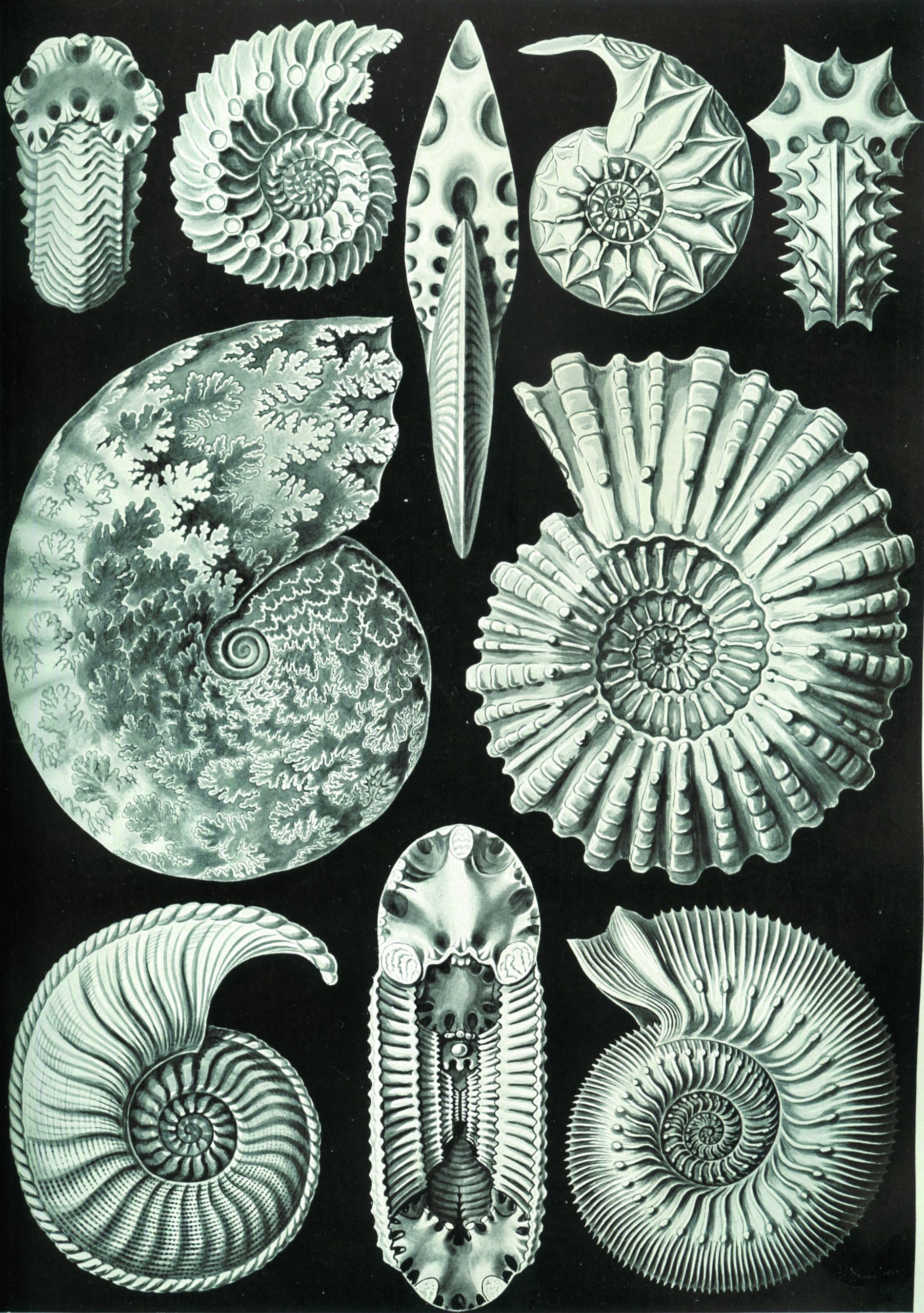

The island is our planet. It is also possible that there is no planet like our island Earth1. It is a microcosm of densely packed time, holding in its strata every accident, incident, upheaval, motion, and collision. Current continents were once islands, vast floating landmasses breaking apart, Pangea becoming Gondwanaland, the latter becoming India, pushing smaller unfortunate island strings out of its way, on its inexorable drift northwards to ram into Asia. The scar of that prehistoric collision is the Himalayas, which is where I grew up and where I found my first ammonite. Imprint, fossil of a prehistoric marine animal carried on that remorseless migration, 50 million years ago, marooned 3000 metres above sea level. The summit of Everest, the highest point on Earth, is composed of marine corals and limestone. The tectonic plates are still moving, and they were what triggered the deadly explosion of Krakatoa. Such is the story of our planet, the island. If its geology is compressed time, then its creatures are the offspring of migration and place. The island as we know it is on the margins. Breeding on its surface are the peculiar offshoots of its self-containment, and whatever stray embryonic-pods the wind and waves, deposits of guano, soles of shoes and even a spade2 may bring. Whether teeming or barren its animated life is as much a product of its anomalous inner geography as its latitude. It holds within it the knowledge of progression of all life, extinct and extant. And like our planet it is totality hot-housed in isolation, a blip in the immensity of time, an oddity floating in vast space.

Haeckel, Ernst. Kunstformen der Natur.

Leipzig und Wein: Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, 1904.

Plate 44: Ammonitida

The island is cataclysm. Volcanic eruptions destroy in an instant, as they did in the case of Krakatoa. Underwater volcanic eruption, effusion and lava flows painstakingly accumulate till they emerge, sometimes as entire island chains. Anak Krakatoa is a prodigious child that grows 13 centimetres a week. Upheavals can take place over epochs, and are no less dramatic. Atolls, archipelago and reefs are not always volcanic or the outcrops of submerged islands. Even the Bikini atoll reefs, site of so much radioactive death-dealing were built on the fossilised remains of dead coral. Charles Darwin recognised that in the Tahitian reefs, and wrote his first scientific treatise on it. But before him was Johann Reinhold Forster, who a century earlier recognised that the atoll rings that lay just below the surface of the ocean, visible and fragile, were built solely of tiny animalcules, coral and other calcareous creatures that lay their foundations on the ocean floor, miniscule organisms growing in rings as bulwark against the ocean, tenaciously growing in layer upon layer, endeavouring for millennia to reach the light.

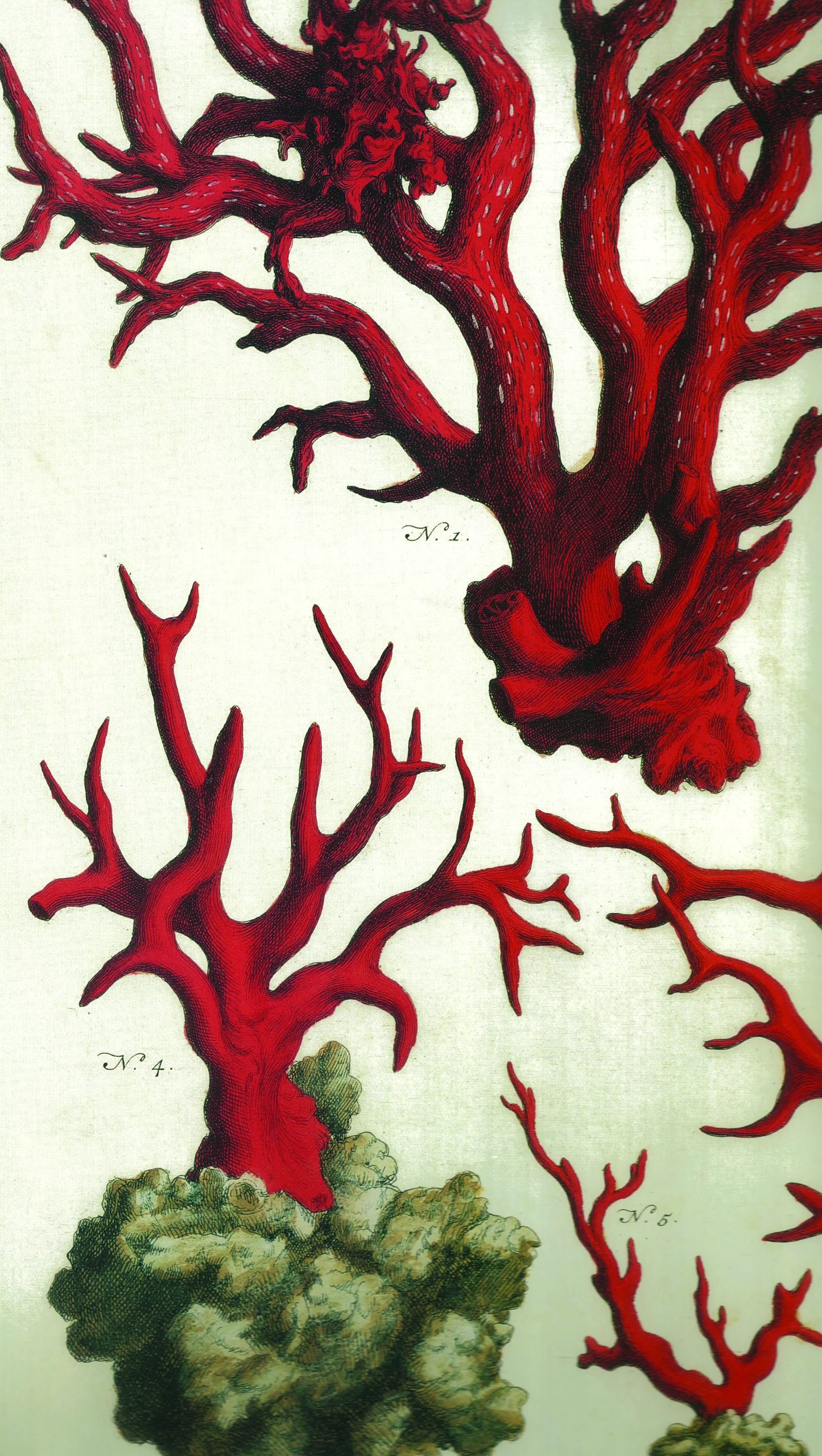

Seba, Albertus. Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata description. 1734-36. Print of ‘Coral’.

Photographed by Shubigi Rao at Artis Library Amsterdam, 2014

The island is out of time. We call our planet Earth when it is mostly water. We have islanded oceans from our consciousness, since we are terrestrial creatures.

Those islands that are far from territorial flexing may appear on maps but are largely immune to the daily mayhems of the continental human. Consider this too, that the out-of-time island has resisted easy demarcation, continental taxonomies and concerns. This island feels the diurnal and seasonal shifts more keenly, shifts that we have largely electrified and artificially cooled or heated away. And yet how far removed are we really? The highest mountains on earth were once shoreline. The Great Barrier Reef is mountain, submerged. The general instability of islands renders them risky propositions, even when deemed to be of strategic importance. The territorial claims of nations can find easy scapegoats in islands, even when they are rocky outcrops barely large enough to hold a flag-wielding human. We creep closer with our reclamations and reshaping of shorelines, foreign sand and soil suffocating coral reefs that never emerged to make it to island status, terraforming the sea into submission. We make bridges and causeways, and they are never enough. We make bombastic declamations like the Palm Jumeirah. But we forget that our demarcations and empires are merely attempts at staving off the inevitable. We are as out of time as the islands we claim.

The island is an ideal/wrecking yard/clearing house/beachhead. It isn’t just the best place to test an unused nuclear arsenal. It is where the writer goes to summon the monstrously fantastic, whether of the pulpier variety (from the The Island of Doctor Moreau, and surely the horror of The Raft of the Medusa), or the impossibly abstract (Thomas More’s Utopia, is set on an island, after all). The island has played site and situation to countless scenarios, tales, fables, from utopian and dystopian, cautionary and moralistic, to fabulous and escapist. Popular culture would tell us that no good comes of breaching that ideal world. The island is only perfect when inviolate. Once we breach the hermetic immune system of the island it can rarely survive in its prior form. Still we dash ourselves on its rocks, beach ourselves on its sands, wash up on it shores. To be marooned (surely the desperate wish of every beleaguered washed-up writer) has a terminal allure, the possibility of untrammelled conjuring within that bounded frame, but piquant with the possibility of no return. From Crusoe to Cristo, the island has been set piece, narrative device, analogue for travail and struggle. Shakespeare frequently hurled his characters’ ships on rocks, forcing their reinvention. All our literary shipwrecks are the dashing of aspirations, of dramatic turns in the narrative. If the idea of a shipwreck seems laughably quaint in the contemporary, think of the appositely named Lost, where the island provides the setting for an outrageous, thoroughly implausible, infuriating and completely addictive set of time- and place-warping situations (at one point the island snaps out of existence to reappear elsewhere, like the Slavic Buyan), intermeshing contradictory timelines and narrative, impossible characters (one being composed of well, malevolent smoke). As a writer, try pitching that, sans island, to a TV production studio or channel. To me the anxiety of Lost had a distinctly nuclear-ticking-clock flavour, where the inexorable countdown always reset, and the ever-present unidentifiable menace was the constant, curiously unreal spectre of MAD.3 The island of Lost was a Cold War relic, because islands are where we rear our monsters, even the dead ones. The rejuvenation of the Jurassic had to occur on an island and over three sequels no less, with a fourth due this year because apparently we can never have enough of giant lizards on islands. It is on islands that we find our King Kongs and we inevitably, foolishly import them into the mainland with justifiably dire consequences. Sometimes they import themselves, as barbed stabs of our consciences, like Godzilla and other kaiju. Invariably they are larger than life, because only on islands thar still be monsters, and as Lord of the Flies showed us, frequently those monsters be we.

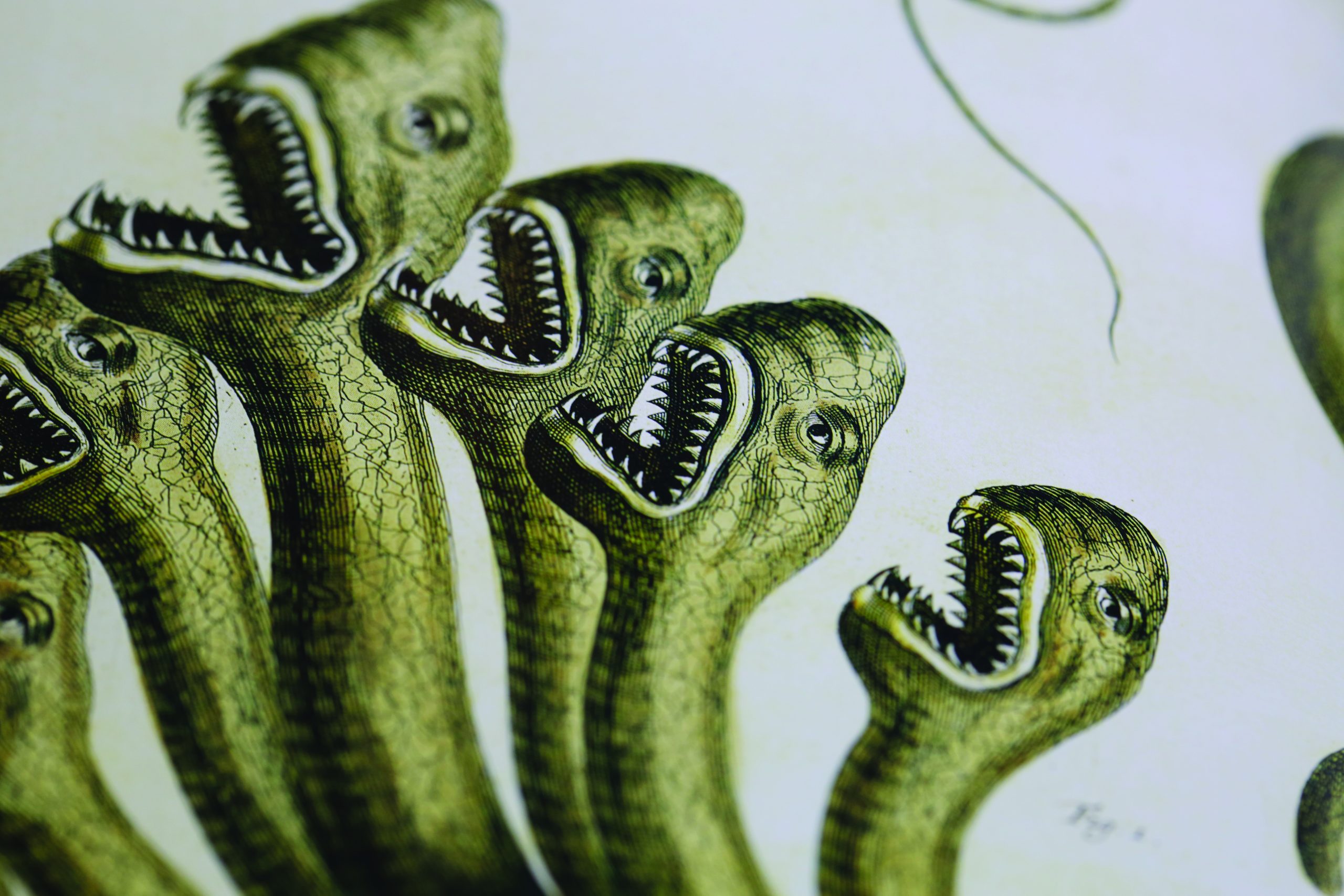

Seba, Albertus. Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata description.

1734-36. Print of ‘Seven headed hydra’.

Photographed by Shubigi Rao at Artis Library Amsterdam, 2014

The island is epiphany myth-maker. The island is the X marked on a map, it is always the site of buried treasure, bodies and secrets. Perhaps the biggest secret treasure to be found was in the Galápagos. The legendary voyage of the HMS Beagle still captures popular imagination, and the finches of the Galápagos will always credited as having triggered Darwin’s epiphany. Like all stories of secrets and treasure it perpetuates a falsehood, that of the Eureka moment being the turning point in great endeavour. That buried treasure is discovered in a cinematic moment of inspiration belies the actual labour and intensive study. The 19th century Dutch naturalist Maria Sibylla Merina’s illustrated masterpiece on metamorphosis in insects was the outcome of living in Surinam. In Darwin’s case, after the famous Beagle voyage it took two decades of painstaking work, tackling irreconcilable, irreducible and prevailing ideas, of intensive study into disparate subjects that led to the development of his theories. Leonard Mlodinow mentions one by-product of his output being a 700-page monograph on the lowly barnacle. And yet it is telling that to formulate the story of all life on our planet, Darwin (and Alfred Russel Wallace in the Malay Archipelago) had to read the island to comprehend the mainland.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. Over de voortteeling en wonderbaerlyke

veranderingen der Surinaamsche insecten. Amsterdam, 1705.

Film still by Shubigi Rao, at Artis Library Amsterdam, 2014.

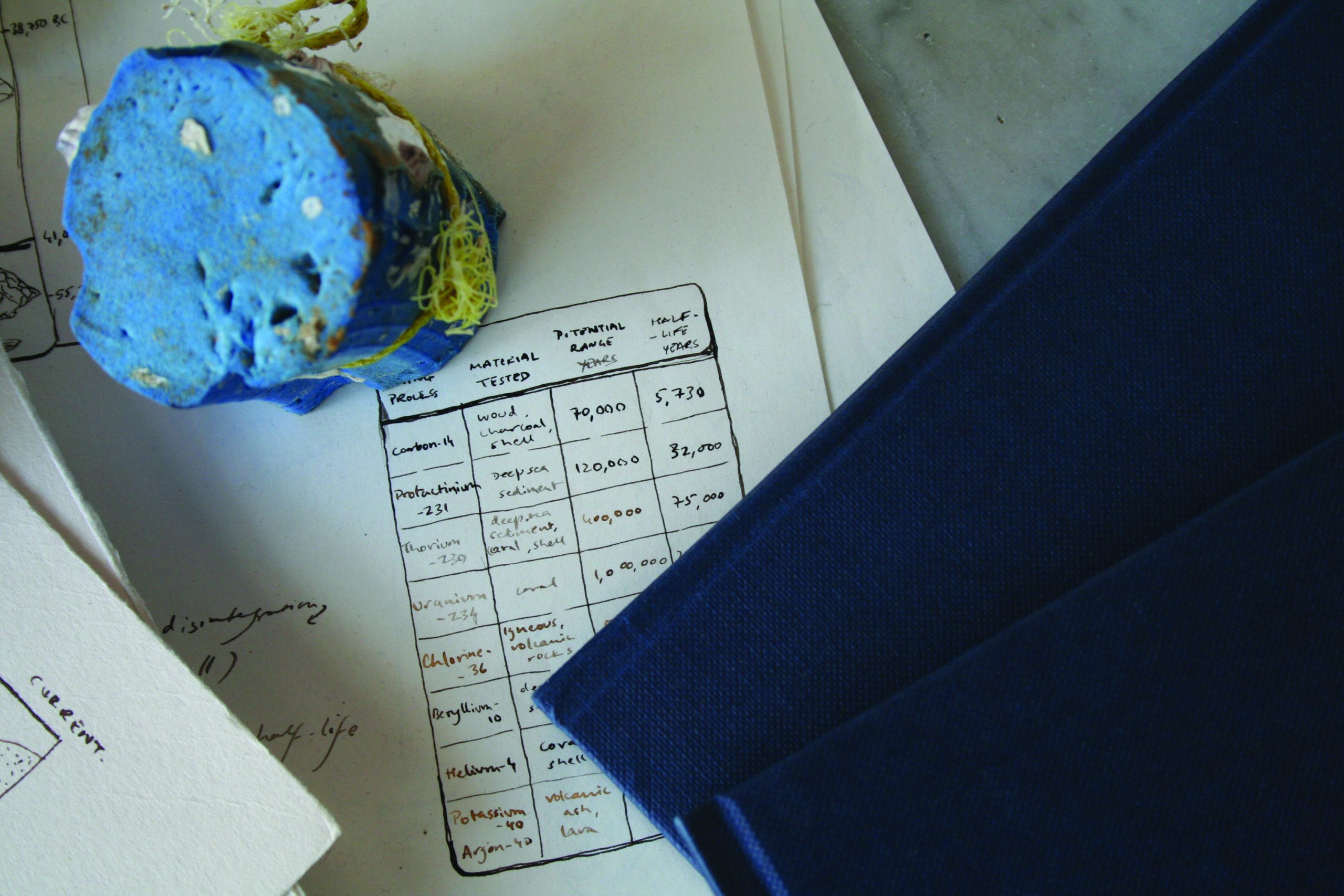

Barnacled artefact collected on East Coast of Singapore in 2003 by Shubigi Rao,

pictured here with notes and observations. Collection of Shubigi Rao.

Photo courtesy of Michael Lee

The island is bewitched. Cargo cults, cannibals and cooking-pot missionaries.

The island is a gag. The default sites for nuclear tests are the Nevada desert and the atoll – the deserted and the island. These are the tired tropes of poor interview questions and hoary jokes, and countless cartoons with a single coconut palm and bearded castaway. It is situation comedy at its simplest and yet most enduring.

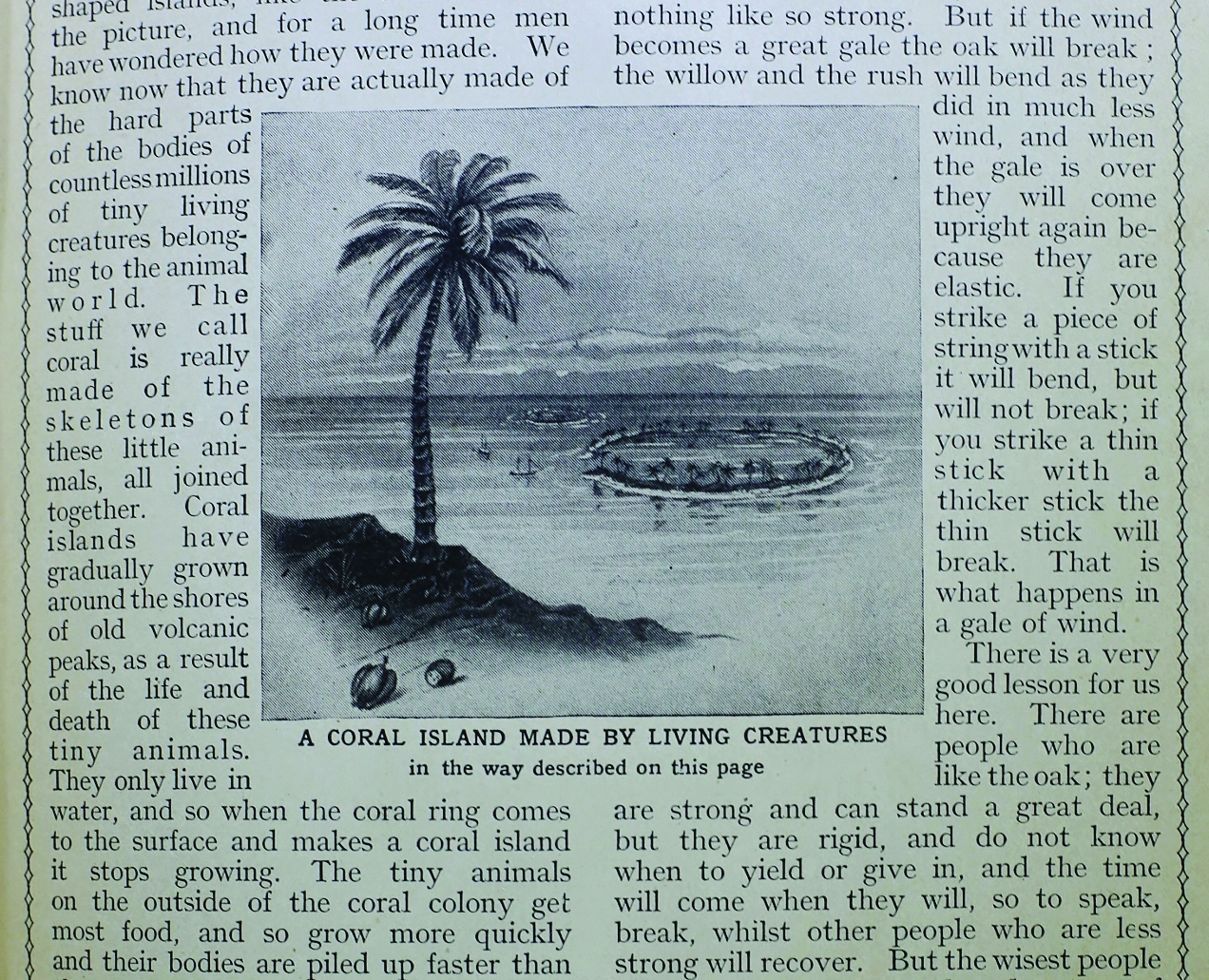

Mee, Arthur; Thompson, Holland. The Book of Knowledge.

London: The Educational Book Co. 1918. Vol. 4, p 921

‘Islands made by coral animals’.

Collection of Shubigi Rao

The island is our brain. There are many realms left to explore – the vast ocean seabed with its bizarre creatures of the deep and teeming microbial life, the immeasurable universe, and the inscrutabilities of the human brain. This floating walnut, dreaming in the sun, with its insular climate and life, is a self-contained bubble yet sensitive to all stimuli that lap up on its shores. It is the repository where our worst fears and our escape plans cohabit. Lush and arid all at once, our brains grow rings of sharp reefs as we mature, so that it is only when we identify ourselves as discrete, when we recognise the isolation of our carefully maintained inner climate that we are truly, and finally adult.

The island is language. Discrete and idiomatic, it develops its own peculiar grammar, slippery dipthongs and plosive sounds, and it resists easy translation. The forked tongue of the natives of fabled Taprobane was divided such that “with one part they talk to one person, with the other they talk to another”4. The colloquialisms of the Galápagos have entered our vernacular, even as we wreak havoc on theirs. The 400 remaining Jarawa of the Andaman Islands call themselves aong or ‘people’, but to their traditional enemies Järawa means ‘foreigner’, and that is how we know them. The animated patois of island life is the curious idiosyncrasy of the Australian marsupial, the oxymoron of the flightless bird, the preposterous absurdity of the blue-footed booby, the mythic genealogy of the komodo, the irrational idiom of the duck-billed platypus, and the indecipherable metaphor of the Singapura Merlion.

The island is memento. Here in Singapore, we are the Island, but our 60 stepsisters are also islands, though we sometime forget their names. These outcrops, addenda to the main-Island, offer possibilities of what-was and what-we-probably-miss-but-can’t-quite-name. Some offer day-trips to nostalgia, epigrammatic non-airconditioned escapes to be Instagrammed when back on the main/is/land. Some can be cycled-through like a visiting dignitary touring the provinces, marvelling at the trees (fruit growing! durians!), fearful of its feral fauna, exclaiming at the ‘simple lives’ of its natives. Pulau Semakau now offers recreational activities, but I hear that no one is nostalgic for it, this future midden-heap, a more densely packed, stratified snapshot of the cremated detritus of our lives.

The island is sinking. And with all things finite and doomed it carries its own mythology and wishful imaginings, of paradisiac absolutes like Atlantis, and the hellish come-uppances of morality tales, sinking into that long sleep of the deep. One wonders how a sunken Venice would be reimagined, mythicised in future lore. Would the biannual descent of the hedonists of the art world be held responsible for its punishment by submergence? Would disaster tourism prevail, and its piazzas be thronged with rubberneckers in rubber-suits? Would its lost frescoes, domes and sighing bridges become an underwater theme park for intrepid honeymooners? Would it be a cautionary tale of the castles-built-on-sand variety, of building on terra that is barely firma? Or would it perhaps be of the foolish but undeniably Romantic human spirit railing against the inevitable tide?

Garbage on East Coast beach, Singapore 2003. Photos courtesy of Shubigi Rao

The island is mobile. India was once an island (and still moves north at about an inch a year), which makes me an islander twice over. There was the perpetually peripatetic, mythic Taprobane, a cartographic anomaly, an ambulatory Never-land till it was banished by modern thought, along with other phantom islands. The legendary Sargasso Sea is now rivalled by massive floating islands of micro-plastic and other garbage in the Pacific. There have also been sightings of one composed solely of ping-pong balls, and another of Lego pieces, and of rubber ducks that have been sporadically washing up on beaches since the 1990s. Not all our new mobile islands are flotsam - we have (Mobil) oilrigs, floating platforms, carriers and patrolling navies. Colossal container ships, super tankers too massive to dock, waiting patiently offshore, occluding the horizon all along Singapore’s eastern shore. I hear that modern shipping is a marvel of technological navigation. I also hear that if you’re a castaway, the likelihood of being crushed under the hull is higher than being rescued, because you are too small to be sighted on today’s impressive navigation systems. When I think of stowaways I think of Darwin’s barnacle, the scourge of shipping, and how the increasing acidification of the oceans thanks to fossil-fuel use will result in its destruction. I think of how the barnacle is the catalyst of its own obliteration – by reducing speeds, ships are forced to burn more fuel, further acidifying the oceans. This may be one of the very few happy outcomes of climate change, another inexorable force that will eventually submerge islands, make islands out of lowland, and set people and cultures adrift and unmoored. The Maldives will probably cease to be islands in my lifetime. We now have a neologism – climate-refugees.

The island is death. There have always been floating islands of people. The year I was born, they began to call them boat-people, because to us of the mainland they are stateless and therefore nameless, and, like the island, they are marginal, marooned and are all too often items to be quarantined. There are people lost at sea, not far offshore from where I write this in my territorial bubble. They say Singapore is also an island, and therefore too small to allow landfall. Malaysia and Indonesia will tow in these islands of the disposed, confine them for a year and then, resettle them elsewhere or repatriate them to the hell they fled. As I write this I think about the news today, where they discovered that those who had previously survived months of being marooned at seas finally made landfall, only to be sunk in mass graves.

The island is organism, single-celled. The island is interlude. The island is playground. The island is prison, penal colony. The island is escape. The island is freedom. The island is knowledge, a library. The island is a lie. And like all impossible, irresistible fictions, unknowable and perfect, lost in the instant it is found, the Island is singular.

Footnotes

1 We are not wholly convinced of that. Perhaps there are parallel universes, but then again, even an infinitesimal difference in each would render all earths different and therefore unique.

2 In a book from my childhood I read an account by Sir John Hooker where, leading an exploring party on “a lonely uninhabited island at the other side off the world” they found some common English chickweed. Following the patches of the plant, they came upon a mound covered in it. The mound was the grave of an English sailor who had died at sea, and Hooker realised that the chickweed seeds had probably been carried, and transplanted by the gravedigger’s spade.

3 Mutually Assured Destruction, a hellish and hysterical way of preserving the Cold War détente.

4 Diodorus Siculus, in Thomas Porcacchi’s Isole più famose del mondo. Venice: 1572

Essays

All The Same But Different: Between Islands

Prologue

There are two island stories to be told, historically interlaced through the scientific voyages of the HMS Beagle that had begun in the 1820s. In 1835 when Charles Darwin visited the Galápagos Islands, he was to see and gather the materials necessary to completely rewrite the theory of evolution. As a result, in 1859 he published his most famous work The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. But to this, we should add the Falklands and the islands of Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago of islands lying to the south of Argentina and Chile.1 Captain FitzRoy moored the Beagle, enabling Darwin to go onshore for some weeks on the islands and Falklands, collecting fossils, plants and animals. As a result of this preliminary work, he decided to do comparative studies to better understand how similar species adapted to different environments. The Beagle then continued on in its long five-year journey up along the western coastline of South America to where the Galápagos lay.

The Galápagos Islands is the point of reference for the Galápagos Syndrome (Garapagosu-ka), a term of Japanese origin, which refers to the isolated development of a globally available product, a phenomenon experienced by Japan as a relatively insulated nation.2 The term arose as part of the dialogue about Japan’s position as an island nation, and the subsequent anxiety it produced about being isolated from the world at large.

The Galápagos Islands lie 600 miles west of South America, off the coast of Ecuador and were first discovered by Europeans some 300 years ago in 1535. The bishop of Panama, Tomas de Berlanga, had sailed to Peru to settle a dispute between Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro after the Spanish conquest of the Incan civilisation in the Andes. The bishop’s ship had encountered strong currents that had carried him out to the Galápagos.

In 1570, the Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius charted the Galápagos Islands3. Calling them the ‘Isolas de Galápagos’ (Islands of the Tortoises), Ortelius’s recognition was based on sailors’ descriptions of the many tortoises inhabiting the islands. There are 10 main islands, and some smaller ones, all formed from the volcanic rock basalt. But the Galápagos Islands were rarely visited and by the 17th century, were ideal bases for pirates who preyed on transiting galleons and coastal towns. The Islands also drew whalers and sealers, with the promise of fur seals and capture of giant tortoises, which could be kept alive in the hold of ships for up to a year with no food or water. As a result, the tortoise populations were decimated, causing the extinction of several species.

Darwin was initially a ‘Creationist’ until his return from the Galápagos Islands. Up until Darwin’s work, evolution had been defined as changes in heritable traits of biological populations over successive generations. The Frenchman Jean Baptiste de Lamarck (1744-1829) had proposed a theory of transmutation and evolutionary processes, calling his theory “transformism” rather than “evolution”. Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace, the British naturalist, questioned how characteristics could be passed onto offspring. Departing from de Lamarck’s theory, they proposed alternatively a process of natural selection and branching tree of life. This gave rise to the theory of diversity at every level of the biological organisation, including the level of species, individual organisms and molecular evolution.

The Beagle

In late December 1831, FitzRoy, with his crew and the young Darwin, left England to take a five-year scientific and geographical voyage around the world. FitzRoy was also a naturalist and had wanted another naturalist to help with the collection and identification of specimens. Darwin was available and had been recommended. He was only 22 years old and fresh out of university, but he had been educated to become a naturalist and was a trainee pastor. Darwin had also studied informally with the great Scottish geologist Charles Lyell. As a boy, he knew the Latin names of a great many plants and animals, and avidly read Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne and other books, including that of Humboldt and his exploration and discoveries in South America.

At the start of Fitzroy’s return voyage to the region in 1831, Darwin had had some experience of collecting beetles and small sea creatures, but regarded himself as a novice in natural history. With a strong interest and training in geology, his plan for the Beagle voyage was twofold — to continue his own investigations of geology and marine invertebrates, and to collect specimens of other organisms that might be new to science.

Tierra del Fuego and the Fuegans

The ship’s first stop was the desolate Cape Verde archipelago off the coast of Africa, distinguished by is volcanic landscape. They then travelled up and down the West and East coasts of South America. Darwin collected specimens from the rain forests of Brazil, and the Andean plains between Chile and Argentina, and both the Falkland Islands and Tierra del Fuego that lay around the southern tip of Chile and Argentina.

There were others on board the Beagle, most significantly three Yahgan Fuegans, who were being returned home to their native land Tierra del Fuego, after having been taken to London by FitzRoy, the year before.4 They were nicknamed by the sailors as ‘Fuegia Basket,’ a nine-year old girl whose original name was Yok’cushly, ‘York Minster’ (or El’leparu) and ‘Jeremy (Jemmy) Button’ (or O’run-del’lico), a 14-year old boy, who was paid for with a mother-of-pearl button in exchange.5 The capture of these Fuegans followed an incident in which some Fuegans had stolen one of FitzRoy’s whale-boats. After recovering the boat, FitzRoy decided to take the young Fuegans to England, including another young Fuegan man, ‘Boat Memory’. FitzRoy’s plan was to educate them as part of an evangelical experiment. ‘Boat Memory’, however, died of smallpox on arrival in London, while the others were ‘educated, civilised and Christianised’ and taught to speak English. They were subsequently presented to King William IV and Queen Adelaide.

The Galápagos Islands

Three years and nine months after leaving England, the ship stopped over in the Galápagos Islands for five weeks, from 15th September to 20th October 1835. Darwin spent about five weeks on the islands: Chatham Island (now called San Cristobal), Charles Island (now Floreana), Albemarle Island (now Isabela), and James Island (now Santiago).

The Beagle anchored first off Chatham Island and, while Captain FitzRoy was surveying the coast, Darwin made five landings. Starting on the 16th September, near what is now Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, Darwin’s Notebook suggests that his main interest quickly became the exploration of a “craterised district”. He made detailed geological notes of the craters, their formation and the lava flows around them. He also noted that three-quarters of the plants were in flower, an essential point for botanical collecting. During one landing he found 10 plant species. The islands were already famous for the iguanas, giant tortoises and finches to be found on them and Darwin was equally impressed. He initially made brief entries on the local reptile life, including the tortoises and iguanas, with a characteristically personal remark: “Met an immense Turpin; took little notice of me.”

Darwin’s first field-note on a bird of the Galápagos was to prove historic. On the day he studied the “craterised district” on Chatham Island, he also jotted down: “The Thenca (is) very tame & curious in these Islands.”6 The point of interest in Darwin’s field notes is how he linked the Galápagos bird with its counterparts on the mainland, asking himself whether there might be similar likenesses between the plants of the continent and those of the archipelago. He wrote: “I shall be very curious to know whether the Flora belongs to America, or is peculiar.”

The Beagle next sailed to Charles Island, where Darwin spent three days exploring and collecting samples of its various animals, plants, insects and reptiles. He made a few short entries in the field notebook. One of the birds he found was another mockingbird. As he was to record later, he found that it differed markedly from his Chatham Island specimen, and from that point on, he paid particular attention to their collection, recording the island where he had found it.

Further, Darwin was told by the local prisoners that each island had its own peculiar tortoise. They weighed up to and over 90kg, big enough for Darwin and others to ride like a horse, and the staple meat for the islanders and visitors alike. They seemed to live a long age and was informed that “the old ones seem generally to die from accidents, as from falling down steep precipices.” Darwin let this local wisdom pass him by, thinking at the time that the tortoises were originally imported by man. Likewise he seemed little impressed by the iguanas, not realising they were unique to the island chain. In a conversation about the giant Galápagos tortoises of which there were small numbers on Charles island, the English Vice-Governor, Nicholas Lawson (who had met the Beagle crew by chance when they landed), observed that the tortoises on different islands showed “slight variations in the form of the shell.” Lawson claimed that he could tell from which of the islands a tortoise had come.

On 29th September the Beagle reached Albemarle Island and the next day the ship anchored in the inlet Darwin knew as Blonde Cove, (now Tagus Cove). Darwin landed on 1st October to examine the volcanic terrain, as well as collecting plants and animals, including another mockingbird. On 3rd October the Beagle moved round to the northern end of Albemarle, and then sailed eastwards to survey the coasts of Abingdon (now Pinta), Tower (Genovesa) and Bindloe (Marchena) Islands. On 8th October the Beagle reached James Island. Darwin went ashore with three others from aboard the ship. During their time there, Darwin explored the inland region and collected specimens with help from the others. He collected evidence to support his theory of the generation of different lavas from the same magma through “fractional crystallisation”. He was also struck by the extraordinary numbers of giant tortoises and made detailed observations of their drinking and feeding habits and calculated the swiftness of their movements. He and his companions were given tortoise meat and found that it was delicious in soup.

Darwin initially missed the evolutionary clues hidden in the finches, finding them very hard to tell apart. In fact, he was not even aware that they were finches at all. He was more interested in how tame they were and surmised they had only recently encountered man, and did not yet have the instinctive fear for people. Darwin found he could even prod them with his gun and many would still sit still. The mockingbirds caught his eye, noticing that some of these were different on different islands, but also that they were all similar to mockingbirds on the mainland. He collected specimens as he had done on the other islands, labelling them separately. Although he collected many finches, he did not label them by island. Fortunately for his later studies, FitzRoy and Syms Covington, (a young cabin boy who had become an assistant to Darwin) were keeping more meticulous records.

Darwin noted that the unique creatures he saw were similar from island to island, but perfectly adapted to their environments which led him to ponder the origin of the islands’ inhabitants. But still the significance of this find did not sink in; he wrote in his Journal of Researches (2nd ed., 1845):

I never dreamed that islands, about fifty or sixty miles apart, and most of them in sight of each other, formed of precisely the same rocks, placed under a similar climate, rising to a nearly equal height, would have been differently tenanted.

Returning home

As the Beagle sailed home towards England during June and July 1836, Darwin had time to prepare and organise into sets the specimens that he would need to hand over to other experts for examination. He took his specimen lists and zoological notes and drew up separate sets of notes for mammals, birds, insects, shells, plants, reptiles, crustaceans and fish, expanding on his former entries. He needed an expert ornithologist’s verdict on his birds, especially his judgement that the three Galápagos mockingbirds should be counted as separate species, and wrote about the mockingbirds in his notes to accompany the specimens. He noted that while the specimens from Chatham and Albemarle Islands appeared to be the same, the other two were different. On each island, each kind had been exclusively found but their habits were indistinguishable. He then developed his brief comment in his zoological notes about the parallel between the mockingbirds and the tortoises.

When I recollect the fact that [from] the form of the body, shape of scales and general size, the Spaniards can at once pronounce from which island any tortoise may have been brought; when I see these islands in sight of each other and possessed of but a scanty stock of animals, tenanted by these birds, but slightly differing in structure and filling the same place in nature; I must suspect they are only varieties. The only fact of a similar kind of which I am aware, is the constant asserted difference between the wolf-like fox of East and West Falkland Islands. If there is the slightest foundation for these remarks, the zoology of archipelagoes will be well worth examining; for such facts would undermine the stability of species.

In the summer of 1837, he started a series of private writings on the subject, focusing on geology more than natural history7. Through 1837 and 1838 Darwin thought to himself about the fixity or mutability of species and the implications of the Galápagos mockingbirds for the possibility that they might change. He then began to write his Zoology of the Voyage (1838-1843), noting: “This bird which is so closely allied to the Thenca of Chili … is singular from existing as varieties or distinct species in the different islands. … This parallels that of the tortoises.” Darwin was beginning to detect deep patterns in the distribution of species that reach between whole classes of the animal kingdom. Darwin had written in his first note on the ‘Thenca’ in his field notebook: “I certainly recognise South America in ornithology; would a botanist?” When he first noticed the bird on Chatham Island, he thought of parallels with other species and he was already collecting the plants of the island for an analysis of their links with the flora of other regions.

From this work, it became clear to Darwin that, over time, different species adapt to their environment. He was intrigued by the fact that each small island had its own characteristic species of bird, lizard and tortoise. Because the islands’ physical and climatic conditions were relatively similar, he reasoned that they were not responsible for these differences. Instead, he concluded that the differences were related to feeding habits. This theory helped form the basis of Darwin’s unprecedented works on biological adaptation, natural selection and evolution.

Darwin had not opened his notebooks on transmutation (evolution) until after his return to England. The Galápagos Islands gave him food for thought about bio-geography, because he recognised that the animals had to come from elsewhere (in this instance, western South America), but only later did he tie these thoughts to evolutionary ideas about adaptation and speciation in isolation. His argument was that if individuals vary with respect to a particular trait and if these variants have a different likelihood of surviving to the next generation, then, in the future, there will be more of those with the variant more likely to survive.

The Galápagos Islands impressed Darwin more for what they said about bio-geography and adaptive differentiation than what they said about natural selection. The iguanas came in more than one form; there was a marine and a land iguana that were unique in the world. Darwin managed to decipher the marine iguana’s unique ecology from his observations, concluding that they fed on seaweed at the bottom of the sea around the coast. Darwin did not recognise the finches as finches, thinking they were different kinds of wrens, ground finches, and other birds. Darwin set about sorting his specimens, and as a result, figured things out. He needed help to classify all his many specimens and these experts often spotted what Darwin missed. From them he learned that each island had its own finch species.

Darwin offered his collection of bird specimens to John Gould, an ambitious young bird illustrator who was rapidly building a reputation as an ornithologist. Gould responded swiftly and positively with a series of presentations of the specimens at meetings of the Zoological Society of London. Gould confirmed Darwin’s suggestion that there were three species of mockingbird in his Galápagos collection, though he changed the grouping of two of the specimens. He also pointed out to Darwin that the many birds he had identified as finches and collected on the different islands, often without recording which, should be grouped together with a number of other birds Darwin had identified as wrens, ‘gross-beaks’ and ‘Icteruses’ (relatives of blackbirds) as “a series of ground Finches which are so peculiar as to form an entire new group containing twelve new species.” Darwin was fascinated at once by what the new grouping revealed about possible evolutionary adaptations in the archipelago but, found that he could not study the distribution of the finches between islands because he had failed to identify from which of the several islands he had collected many of his specimens.

As he developed his ideas about evolution in the late 1830s and early 1840s, he became more and more confident in biogeography and adaptive differentiation’s power to explain8. However, the evidence on which these ideas were based needed to be built up before he could apply them to other cases. The three species of mockingbirds on three of the islands would not be enough to persuade. He had given his collection of Galápagos plants to John Stevens Henslow shortly after his return to England. Henslow had been Darwin’s mentor at Cambridge University and introduced him to the study of the geographical distribution of species. Moreover, he had explained the special interest of the links between the flora and fauna of oceanic islands and the continents they were close to, and the Galápagos was an obvious case for further study.

In 1843 as a result of Henslow not having enough time to study, Darwin arranged for the young botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker to take over the collection of specimens he had brought home from Galápagos. Darwin was eager to hear how many species were shared with South America and how many were unique to the Galápagos and more so, how many were unique to a single island. Hooker found that the flora had many close and clear links with the plants of South America, and his conclusions on the distinctiveness of the archipelago and individual islands were astonishing. Of a total of 217 species collected, Hooker found that 109 were confined to the archipelago and 85 of those were confined to a single island.

After studying Covington’s and FitzRoy’s more carefully labelled specimens, Darwin could see that each island had its own unique species, some endemic to particular islands, all with unique bill shapes and sizes. He concluded in his Journal:

Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.

By this time, some 10 years after he had left the Galápagos, Darwin explained that when he compared together “the numerous specimens, shot by myself and several other parties on board, of the mocking-thrushes”, he found: “to my astonishment, I discovered that all those from Charles Island belonged to one species … all from Albemarle Island to [another] and all from James and Chatham Islands to [a third].” (Journal of Researches):

The distribution of tenants of this archipelago”, he wrote, “would not be nearly so wonderful, if for instance, one island has a mocking-thrush and a second island some other quite distinct species... But it is the circumstance that several of the islands possess their own species of tortoise, mocking-thrush, finches, and numerous plants, these species having the same general habits, occupying analogous situations, and obviously filling the same place in the natural economy of this archipelago, that strikes me with wonder.

In 1845, Darwin published a general account of his observations as The Voyage of the Beagle. He then published books on the Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs visited during his trip, as well as the Geology of South America. Darwin’s eventual conclusions, stemming from his first question about the birds and plants of the Galápagos, were to feature in one of the most important passages in The Origin of Species:

The relations just discussed … [including] the very close relation of the distinct species which inhabit the islets of the same archipelago, and especially the striking relation of the inhabitants of each whole archipelago or island to those of the nearest mainland, are, I think, utterly inexplicable on the ordinary view of the independent creation of each species, but are explicable on the view of colonisation from the nearest and readiest source, together with the subsequent modification and better adaptation of the colonists to their new homes.

Viajar, sin Embargo

Airmail Painting No. 178 1986-2007

tincture, buttons, ink and photosilkscreen on two sections of kraft paper

80 x 115 1/2 in/203.2 x 293.4 cm

Image courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

These words capturing one of his key points about evolution by natural selection. For those born with characteristics that make them best suited to their environment are most likely to survive and successfully produce offspring.

Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.

Conclusion

Many years later the Chilean artist, Eugenio Dittborn, was reading Darwin’s account of his trip on the Beagle and saw FitzRoy’s drawing of Jemmy Button. Dittborn subsequently produced a series of airmail paintings that included images of the Fuegans, in particular Jemmy Button (see Airmail Painting No.178, 1986-2007). He went on to use the image of Button again and again as in Airmail Painting No.102 (1993). They became what Guy Brett described as “ ‘a graphic mark’ (that) is also a ‘life trace’.”9 This idea becomes of central importance in defining the character of Dittborn’s Airmail Paintings and his practice.10

Moreover, the idea of exile as an allegory of these works is related to the notion of displacement, and that of travel. One of the critical values of Dittborn’s Airmail Paintings is the restoration of their subject. By transferring the images from one referential field to another, Dittborn makes the sources of these found images interconnected and recombines their links with history, redressing the official archive. Transit becomes the possibility for of the subject’s survival. Nelly Richard notes: “While the Chilean State tried to put out of circulation some determined subjects to condemn them to oblivion, Dittborn’s Airmail Paintings put back into circulation images of subjects condemned to forgetfulness. The artist became a kind of “guardian of memory,” the one which was suppressed by the official apparatus.”11

A story of islands then.

To Return (YVR)

Airmail Painting No. 102 1993

paint, stitching, charcoal and photosilkscreen on six sections of non woven fabric

165¼ x 165¼ in/420 x 420 cm

Image courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

To Return (RTM)

Airmail Painting No. 103 1993

paint, charcoal, stitching and phototsilkscreen on six sections of non woven fabric

165¼ x 165¼ in/420 x 420 cm

Image courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

This article is based on a series of readings:

Charles Darwin: The Voyage of the Beagle. First published 1839.

Grant, T & Estes, G. Darwin in Galápagos. Princeton University Press, 2009. And various websites: (i) Darwin’s Finches Wikipedia; (ii) The Galápagos Geology: A Brief History of the Galápagos; (iii) Galápagos Islands History and Charles Darwin.

Footnotes

1 The Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, who circumnavigated the earth in the early part of the 16th century, named the islands ‘Tierra del Fuego’, after seeing the campfires of the Fuegan tribes along the coastline. In the late 19th century the Reverend Thomas Bridges (1842-1898), the first permanent white resident of Tierra del Fuego, published the first dictionary of the native Fuegan language.

2 The term was originally coined to refer to Japanese 3G mobile phones, which had developed a large number of specialised features and dominated Japan, but were unsuccessful abroad.

3 Abraham Ortelius is known as the creator of the first modern atlas.

4 FitzRoy’s first survey of the Tierra del Fuego region was from 1826 to 1830.

5 In 1855, a group of Christian missionaries visited Wulaia Bay on Navarino Island to find that Jemmy Button still had a remarkable grasp of English. Some time later in 1859, another group of missionaries was killed at Wulaia Bay by the Yaghan, supposedly led by Jemmy and his family. In early 1860, Jemmy visited Keppel Island, giving evidence at the enquiry into the massacre. He denied responsibility. Some years later in 1863, the missionary Waite Stirling visited Tierra del Fuego and re-established contact with Jemmy. From then on, relations with the Yaghan improved. In 1866, after Jemmy’s death, Stirling took one of Jemmy’s sons, known as Threeboy, to England.

6 ‘Thenca’ is the Spanish name for the thrush-like mockingbird from the west coast of South America.

7 Darwin had written to his sister Catherine “there is nothing like geology; the pleasure of the first days partridge shooting or first days hunting cannot be compared to finding a fine group of fossil bones, which tell their story of former times with almost a living tongue.” (April 1834). The total bulk of Darwin’s Geology Notes (including Paleontology) were nearly four times greater than that of the Zoology Notes and Natural History.

8 Darwin had also read Malthus’s Essay on Population (1798) in 1838 and started applying Malthus’s ideas to natural organisms by the 1840s.

9 Brett, Guy. La Casa, the Letter, the House: (transperipheria) 5 Airmail paintings from Chile: Eugenio Dittborn. Sydney: Australian Centre for Photography, 1989.

10 See Dittborn, Eugenio. Mapa: The Airmail Paintings of Eugenio Dittborn 1984-1992. (London ICA, 1993).

11 In Richard, Nelly. Margins and Institutions. Melbourne: Art & Text, 1986.

Essays

“Who is thy wife? Who is thy son?

The ways of the world are strange indeed.

Who art thou? Whence art thou come?

…behold the folly of man:

In childhood busy with toys

In youth bewitched by love

In age bowed down with cares…

Birth brings death, death brings rebirth

Where then oh man is thy happiness?

Life trembles in the balance

Like water on a lotus leaf”1

This was the articulation of the question of life, existence, and self, emphatic in the scheme of Shankara2, a sixth century philosopher from south of India. As evident, the verse resonates a sense of self as a perpetually fluid island, appearing with birth, submerging in the sea of life, and disappearing by death, only to reappear in due course. To correct, it is the upheaval of fluid island-self marked by endless changes in the stages of existence. This is very similar to the ideas of Buddha who also suggested that life, pleasure, rebirth and the cycle from birth to death to rebirth is indicative of suffering, which can only end when this cycle itself is broken by achieving nirvana or the Buddhist state of ultimate bliss beyond which there is no life, death or resultant suffering. However, we exist in the world because we are without nirvana and hence we are subject to perpetual changes. How can one make sense of a self in this utterly helpless flux? With this question, the philosopher Shankara travelled the length and breath, from south to north, of ancient India, learning and critically engaging with scholars of various schools of philosophy. Thus, he reached a village named Mahishi, in the Maithili speaking region in the north, now situated within the official map of Bihar abutting the borders of Nepal via river Kosi. Mandana Mishra, a renowned scholar of Mimamsa, one of the old schools in philosophy in ancient India, lived in Mahishi. Mandana was a proponent of the awakening of self within social institutions of conjugal life. In other words, for Mandana, the vocation of a householder was superior to that of a monk, a renouncer ascetic. Shankara offered to debate with him on this issue. Mandana’s wife, Ubhaya Bharati, a scholar of repute too, was the judge of the debate between the two scholars. The prolonged debate that entailed elaborate logical arguments resulted in the defeat of Mandana Mishra. Shankara proved that the ultimate goal of self is to recognise the limits of apara vidya3, the knowledge imposed by the perceptions embedded in social existence. This is the domain of maya (approximately translated as worldly illusion and creative energy), which the self ought to be transcending to arrive at the superior para vidya, self-realisation of the indwelling Brahman, the absolute truth! However, upon the defeat of Mandana Mishra, the judge of the debate, wife of Mandana Mishra, Ubhaya Bharati, announced: the debate was not over yet! For Mandana was a householder and he was only one part of the full unit. The other part was his wife, who must be defeated in debate for the complete defeat of her husband. Thus the debate with Shankara continued. The very first question Bharati raised was about the intricacies of sexual-conjugality in the life of a householder. In other words, it was about the socio-cultural and sexual embeddedness of a self. Shankara, being a renouncer-ascetic, had little knowledge of conjugal life and its sexual dynamics. He expressed his unawareness of the issue under question and requested Bharati to lend him a little time to undertake adequate research. He returned and answered the questions of Bharati satisfactorily. He was the victor indeed.

But the above episode is not to be read only as an instance of Shankara winning an intellectual debate. The secret of the episode is in the socio-cultural embeddedness, institutional bonding, and the mundane conjugal life of a householder. The crux of the story is the prerequisite acquaintance of an island-self with pleasure and pain of living. Mere knowledge of the transcendental self could not make for truth; the mundane maya also holds keys to opening doors in the passage of the transcendence. This could be deemed the becoming of a fluid island-self.

At this juncture, it is imperative to ask: how does it all surface in our contemporary visual worldview? Could this instance from conjectural past be of any significance in our contemporary socio-cultural landscape? Are we islands named Aham Brahmsmi? And if we are, what is the undercurrent sociability thereof? A humble proposition is that one is the island-self named Aham Brahmsmi with deeper socio-cultural undercurrents connecting Shankara’s apara vidya and para vidya, maya and brahman, mundane and absolute!

This process of becoming a fluid island-self must not be confined to the discursive trope of the written text alone. It must unfold in the domain of the seen, even though seeing does not become believing! As a proposition, the following are a few images from contemporary India. Some of them echo undying social stereotypes. But then, the latter is the easiest tool, to continue and discontinue, toward further creations in art, poetry, literature, and aesthetics. The trope of modernity too provides for continuity and discontinuity.

On a Visual Trope

The following photographs from contemporary India present a familiar socio-cultural landscape. However, this visual familiarity allows for a critical engagement with the undercurrents of an island-self.

An Island Faraway

Photo credit: Dev Pathak

An island faraway seems static, in a frozen frame, muffled in tides and clouds. However, could one deny the inherent dynamics? An island faraway tends to sail across the river along with the sailing canoes.

Sailing across the River

Photo credit: Sasanka Perera

Folks carry wind, dust and essence of a faraway island with their selves. With sailing canoes, the fluid island individual self crosses beaches and barriers. Trembling on the waves, however, they tend to find repose, vanity of meditation.

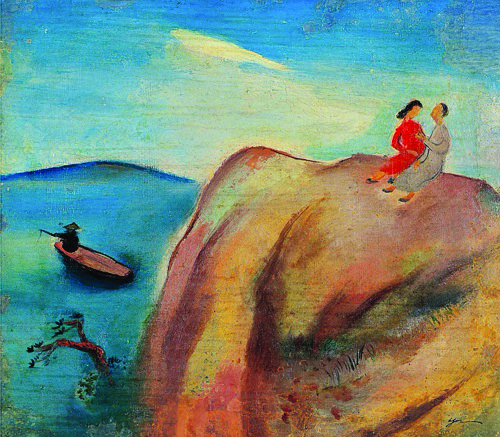

An Island named Aham Brahmsmi

Photo Credit: Dev Pathak

The repose is as momentary as is the identity of self. For liminal can seldom be permanent. The journey continues in quest of self, and one finds oneself amidst myriad structures.

Amidst

Photo Credit: Dev Pathak

Maya’s Self

Photo Credit: Dev Pathak

Maya entails creative energy and hence the process of becoming as well as unbecoming continues. It often leads to many gods and ways of performing devotion.

Ritualised

Photo Credit: Sasanka Perera

Devotion is however not merely for surrender. One worships a god and one becomes an extension of divine. The mortal divine indulges in regenerative plays.

Play with Maya

Photo Credit: Dev Pathak

Many more appendages to the island-self stem from the play with maya: the pleasure of winning and pain of losing, the joy of union and sorrow of separation, anguish of falling and ecstasy of rising!

Meditation on the Ruins

Photo Credit: Dev Pathak

An island-self reaches an inevitable destination. Some ruins already in existence and some decay in the offing, meditation of the island-self is to reach a reckoning leaving little to regret!

Modern Imagination of Self

Moreover, this is crucial to fathom this phenomenon in the discursive framework of modernity, selectively looking at literary imaginations. This is not a comprehensive perusal of the vast corpus of knowledge on modernity. Instead, this is a modest attempt to put some more bones and flesh to the notion of Fluid Island-Self. This is to reason with humane attributes of the metaphorical island named Aham Brahmsmi!

Unlike the fluidity of the island-self, the scheme of modernity had put existence into strict binaries. In contrast with fluidity, it perceived either an otherworldly ascetic or a this-worldly householder. This was the famous binary opposition of an entirely (En)lightened self of Immanuel Kant or a totally chained cavemen of Plato. The liberated self had to live a monastic life, away from the hurly burly of socio-cultural happenings. And the chained men had to be the pragmatic individuals of this world, capable of engendering the structure in which they lived. But then, some of these chained cavemen also appeared to be a little strange. For example, Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray! Gray was a man of this world. But he did not follow the principles of the cave, or the social codes of sexual liaisons. Seeking for liberation from this world’s dictums, he committed ‘sin’ since he did not walk into an ascetic’s monastic world. His liberation was not-liberating since he was sexually and selectively anarchic only in pursuit of hedonism. His anarchy was for the pleasure within this world. Unless his anarchy led him away from this world it was not appropriate in the modern scheme. The adverse impact of the hedonistic anarchy is visible on the portrait of Gray, which he hid in the attic. He did not want to see, quite peculiar of a modern man, his withering self, reflected in his portrait. He too seems to be aware of the misery of being in-between. Wilde makes Gray repent endlessly in the scheme of modern binaries. Either he has to be of this world or of the other world, and not at all a character in-between. In sum, Gray must be consistently an island-self totally chained in this world and hence unmoving.

But then, beyond Wilde’s modern scheme, Gray also presents a case of a fluid island-self. Though it manifests only in Gray’s sexual rampage it is anarchy of self directed toward hedonistic pleasure. If we omit the lamentation of Gray, an imposition of Wilde, it is a perfect case of modern man’s ambivalence.4 This is what makes an island-self to be fluid. Thus, the Cartesian Cogito, intellect free from sensuous body, seems a mere philosophical utopia. For, the scheme of modernity also entailed ambivalence. It allows a protagonist to be in an anarchic pursuit of self with or without hedonism in perspective. The scheme of modernity thus also deals with uncertain, strange, and spontaneous individuality. Moreover, the “modern man in search of a soul”5 created beliefs, mythology, gods and demons of its own. With evident skepticism toward the doctrines and systems of traditional belief, the island-self moves on to find meanings even in the world of utter meaningless. Hence, there is a meaning for even a Sisyphus despite absurdity abounds. There is awareness that everything is like mere cobwebs – meaningless in one breath, but enchanting in the other – for the modern men including Camus’ Sisyphus and Wilde’s Gray. This is the peculiar ambivalence on which scheme of modernity is precariously hinged. The ambivalence of modernity surfaced in art and aesthetics, poetry and literature abundantly. It became thereby possible to juxtapose emotional and intellectual, irrational and rational, subjective and objective, aesthetic and scientific. The Janus- faced modern existence!

At this juncture, it is imperative to briefly turn to the 20th century Hindi poetry for a synoptic comprehension of the elaborate imagination of self in consonance with the imagery of island. Amidst the plethora of poetic imagination in modern India, Agyeya’s poetics unfold a pertinent argument.6 Take for example, the poem Nadi Ke Dweep (Island of a River):7

We are the islands of the river; The river gives us shapes- angles, interior, and exterior; She makes us all rounded; She is the mother; But we are islands; and not streams of the river; Ours is a quiet surrender, stable and still; For, if we float along; we won’t exist; We would erode if we move; And yet we could not be her currents; We would be only mud; And muddy her water as we flow! It is ideal to remain an island; And this is not a curse upon us; This is our decent destiny; We are offspring of the river! Seated in her lap, we are related to the mainland.

The Conqueror Island-Self

Photo Credit: Dev Pathak

The island-self thereby wins over the avalanche of desires, the manifestations of Maya. The typical aspiration of a scholar, philosopher, ascetic, such as Shankara, to attain the self-realisation of Aham Brahmsmi!

This is important to highlight a few key terms in this poem: island, river, shapes, mother, stream, erosion, mud, and mainland! Through these key categories, Agyeya attempts to disclose the deep dispositions of a modern mind. The fear of violating the structure represented by the river, the mother, who shapes an island-self is important issue. The destiny of the static island is not a curse and hence it must not be overcome. And, the island is still connected with the mainland by the virtue of being true child of the mother river. The poem extolls the solitary island and its ability to remain an uneroding entity. If it erodes, it will be only mud and muddy the flow of river. The poet articulates a modern aspiration, in continuity with the scriptural role of the capable intellect, to stand firm in front of manifold temptations and not give in to various desires. Only then, a man could be appropriate in this world and the other world.

But then, this is not the only component of modern man’s disposition. In the anthology of Agyeya, there are several verses to add another kind of human aspiration. Almost resonating the scheme of ambivalent modernity, and adding fluidity to the uncanny certitude of Aham Brahmsmi, Agyeya’s This Solitary Lamp reads:

This solitary lamp, of warmth and affection; Proud and prejudiced, as it may be; Give it to the row of lamp!

Or another important poem, from the anthology titled Kitni Navon Mein Kitni Baar (Many Times in Many Boats):8

From faraway lands, so many times; many rocking boats I embarked; so many times I came toward you; my very own little flame! Amidst the fog, I may not have seen you; but in the faint flickering light of the fog; I could recognise your halo; many a time, patient, assured, unrelenting, un-tired; My unknown truth, many times!

Wandering Time Seeking Self

Photo Credit: Sreedeep

As time ticks away, the self seeks to reach out! It is difficult to ascertain whether this wandering is inside or outside the self. Be it as it may, it reveals an aspiration of the fluid island-self to be in a quest.

Sting of Solitary Being

Photo Credit: Dev Pathak

Needless to say, the quest of an island-self could amount to several existential stings. This eventuates for an island-self into a sting of being. Pristine, pure and petrified ¬– connected with the mainland and yet not able to traverse the passage!

These by no means represent the whole of poetic currents in modern India. That would solicit a discussion on poetic imagination of self in the works of other significant poets, such as Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh among others. The above synoptic view is only to aid in grappling with the idea of island-self in modern context. This establishes not only Janus-faced modernity in India. More importantly, this also underlines human aspirations rendering island self humanely vulnerable. If there is a notion of Aham Brahmsmi presiding the island-self, it is vulnerable to the slippery passages. Even though, Mandana Mishra and his wife Ubhaya Bharati conceded defeat in the debate with Shankara the philosophical proposition of the defeated holds significance: an individual self is socio-culturally embedded while also free to pursue the higher aspirations! This is also reflected in the scheme of modernity wherein liminal is as crucial as relatively durable positions of individuals. The in-between spaces of existence thereby become important for the island-self named Aham Brahmsmi.

Concluding Sociologically!

In more than 2000 words, the above rumination attempts to offer an irritating answer to the equally irritating sociological antinomies. These are the antinomies of self and society, individual agency and social structure, social physics and non-social metaphysics. One can say that Pierre Bourdieu did it long ago. Yes, but Bourdieu failed to think of the divide between physics and metaphysics, didn’t he? Even though many other antinomies were addressed, an unhindered puzzle remained untouched: Who is a self in social context? Is it a mere socio-cultural determination with clear morphology or something more? Emile Durkheim, an early academic in classical sociology, thought of sacred as a collective representation. Thereby, everything religious or metaphysical became components of culturally constructed ‘sacred canopy’ of Peter Berger. An individual self under the sacred canopy lost its individuality. This has been perpetual in sociological reasoning. Even the advent of individualistic perspective, mostly attributed to late modernity, could not come around the real issue: whether a man is only a physical accident in the frame of social biology or there is something more? It seems the question of a self as an Island named Aham Brahmsmi has been totally relegated to the spheres of poetry and literature, art and aesthetics! As if this were a nonissue in typically modern social science, however some psychoanalysts, the renowned renegades of Sigmund Freud, tried to engage with the issue. Well, the ‘serious’ anthropologists and sociologists do not find anything significant about psychoanalysis as such. If anything, it is merely a particular methodological approach and that too heavily contested. Forget about psychoanalysis, social scientists and sociologists in particular are too methodical to even traverse the terrain of individual-islands! They would ask whether they have a methodology to support their observations about Aham Brahmsmi (pun intended)! Hence they have not been able to deal with the myth of living Sisyphus of the modern world though Levi Strauss claimed to lay the cornerstone to understand the myths of the whole world. It is in this context, that this rumination holds significance for a sociologist, and teaches a simple lesson: in the world of heteronomy, an individual self is still grappling with the question of island-self!