VOLUME

Special ISSUE

Arrhythmia

This special volume of ISSUE is dedicated to a series of critical inquiries into the field of performance curricula, pedagogies and practices. Informed by changing positionalities in performing arts education and emerging interdisciplinary approaches in performance and experience making, these inquiries were germinated and crystallised at a landmark conference, Arrhythmia: Performance Pedagogy and Practice, held in Singapore in June 2021 amid a raging pandemic.

Special ISSUE

2022

Arrhythmia

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Essays

Conversations

Emerging Research

Postscript

Contributors’ Bios

Essays

Conversations

Critical COVID-19 Creative Work: Kindness, Care, and Repair

Michael Earley

Artist’s Studio as an Open Space

Melissa Quek

Emerging Research

Dichotomy: Using Dance to Span a Distance

Identity and the Rhythms of Actor Training

The Future of Technical Theatre in Southeast Asia: A Panel Discussion

Muhammad Nurfadhli Bin Jasni

Postscript

Postscript: Murmurs of the Day

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Guest Editors

Felipe Cervera and Darren Moore

Copy Editor

Sorelle Henricus

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Editorial Board

Professor Patrick Flores, University of the Philippines

Dr. Peter Hill, Artist and Adjunct Professor, RMIT University, Melbourne

Professor Janis Jeffries, Goldsmiths, University of London

Dr. Charles Merewether, Art Historian, Independent Researcher, Curator and Scholar

Manager

Sureni Salgadoe

Contributors

Michael Budmani

Chloe Chua

Edmund Chow

Ethan Curnett

Michael Earley

James P. Félix

Peggy Ferroa

Goh Xue Li

Matt Grey

Muhammad Nurfadhli Bin Jasni

Timothy O’Dwyer

Melissa Quek

Peter Sellars

Dayal Singh

Melati Suryodarmo

Filomar Cortezano Tariao

Natalie Alexandra Tse

Soumya Varma

Lonce Wyse

David Zeitner

The Editors and Editorial Board thank all reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments and feedback to the contributors.

Introduction

Special

This special volume of ISSUE is dedicated to a series of critical inquiries into the field of performance curricula, pedagogies and practices. Informed by changing positionalities in performing arts education and emerging interdisciplinary approaches in performance and experience-making, these inquiries were germinated and crystallised at a landmark conference, Arrhythmia: Performance Pedagogy and Practice, held in Singapore in June 2021 amid a raging pandemic. The pandemic was a stark reminder of that which is often taken for granted: how much the embodied and existential coalesce in situ to create magic. The substance of the conference was prompting us to go further afield with renewed vigour to explore new opportunities and give voice to that which is vulnerable—human connectivity. This exploration warranted study, leading to the commission of the conference organisers to curate a series of articles for this special volume.

This is the first special volume for ISSUE in its ten-year history. We are delighted to present this remarkable body of work.

Introduction

Introduction: Arrhythmia

Darren Moore

This special volume of ISSUE features commissioned writings emerging out of the proceedings of the Arrhythmia: Performance Pedagogy and Practice conference held in June 2021. Arrhythmia refers to an irregular heartbeat. It is a medical condition symptomatic of severe heart disease, even indicative of a heart attack. Drawing inspiration from the medical implications of the term, the conference and its ensuing journal volume frames it as a metaphor for the disruption and havoc brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. The rhythms of teaching and learning were disrupted ad libitum, without an end in sight in a rather convulsive manner. The conference and this volume aim to encapsulate this historical moment by gathering artists, performance makers, scholars, students, and researchers to share and reflect on our collective challenge. The articles in this volume express the profound and invigorating experiences of the conference. Arrhythmia was a clarion call to an emerging reality: we had become acutely aware of rhythm in its absence.

As editors, we wanted this volume of the journal to represent the foci of the conference. To draw out international perspectives, situate local practices, nurture emerging research and locate the impact of COVID-19 on performance pedagogies and practices. The contributors reflect a cross-section of the arts community—artists, scholars, social workers, teachers, and students who are both established and upcoming.

The volume is divided into essays, conversations and emerging research. The essays bring scholars’ and artistic practitioners’ theoretical and practical insights into the more significant pedagogical shifts brought about by the pandemic. The keynote conversations by world-leading artists Peter Sellars and Melati Suryodarmo are archived here to offer diverse perspectives around care, hope, and opportunity to the field of performance. Emerging research by both staff and students reflects on experiences of the pandemic within the institutional context. Finally, the editor of ISSUE, Venka Purushothaman, connects the ideas gathered by the contributors to the critical discussions on contagion and collaboration to remind us that what is really at stake is a rethinking of our presence in this world as the cornerstone of pedagogy.

The conference took place while Singapore was experiencing its first significant wave of COVID-19 infections, with numbers escalating quickly from tens to thousands of cases. Since then, and during the production of this special issue, we saw that wave recede only to experience the impact of a consecutive, more significant wave caused by the Omicron variant. The experience marks the transition to living with COVID-19 as an endemic disease. This transition has not been easy, but it demands re-evaluating and re-orientating everyday practices and modes of interaction. We must learn how to live with the virus and move on to co-habit this planet in some semblance of ecological harmony. Editing this issue has been an experience marked by that transition. We are very grateful for the opportunity to edit ISSUE’s first special volume, and in doing so, to contribute to the strengthening of the research culture in the Faculty of Performing Arts at LASALLE.

Essays

Bradycardia is defined as heart rate slower than normal. The normal resting human heart rate is between 60-100 per minute. However, athletes’ hearts may beat less than sixty beats per minute, as their hearts may have been conditioned to do so.

— Cedars Sinai

Knowledge from Narrative

Within a fortnight from the day the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the Corona Virus 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic, three professors of the medical school I graduated from succumbed to the virus; one classmate passed away with a mysterious massive thromboembolism. A month later, on my social media feed, the number of frontline casualties who were colleagues or juniors rose until I stopped counting. The international news was dire enough, but what made my fear worse was that I knew the names of the people who lost the fight. The image of wearing a mask to protect others in order to protect ourselves became a ubiquitous meme of altruism in my head. I posted COVID-19 articles from journals in the hope of spreading scientific facts to the community. The process of writing about it seemed to wipe off the survivor guilt that comes when one has left a profession that is now the sacrificial pawn in this morbid game of chess. I thought that I could keep myself and my family away from the effects of this pandemic if I continued supporting my peers. However, more than a year later, the viral contagion was at our doorstep. My father who has Parkinson’s Disease (PD) developed aspiration pneumonia, a usual complication of patients with PD.1 I booked a flight immediately to Manila. Thankfully, my father tested negative for the virus, but we repeated it just to confirm the result as he was a high-risk patient. By that time, I was already serving my quarantine in the Philippines, and when I reached home after the government-imposed sojourn, I was glad to see him. Unfortunately, his condition appeared to have worsened, so I decided to take him to the hospital.

According to Dr. Dayrit in “The Philippines Health Systems Review,” the country, while home to over 104 million people, offers only 23 hospital beds per 10,000 people in Manila alone.2 During the current pandemic, when the hospitals are overwhelmed with the number of cases, getting immediate healthcare was close to impossible. My father and I were firsthand witnesses to this phenomenon. As the only one in the household who was fully vaccinated against the Severe Acute Respiratory Corona Virus 2 (SARS-Cov2), the causative agent of COVID-19, I was the sole individual who could accompany my father to the non-COVID-19 sector of the hospital. So we got ourselves tested again to prove that we did not harbour the virus and so the doctors could attend to us in the Emergency Room (ER). Still, I had to wait 48 hours in the driveway of the hospital, staving off sleep and exhaustion, before a bed became available in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). What I saw in the news while I was in Singapore became my own reality. I was just fortunate that I belonged to a fraternity of doctors who would not hesitate to help me in my need. But I asked myself ‘what about those who were not as well connected as I was?’ Truly, their situation would have been much worse. My instinct for survival overtook my self-reproach and eventually my dad got better and was discharged on the eleventh day.

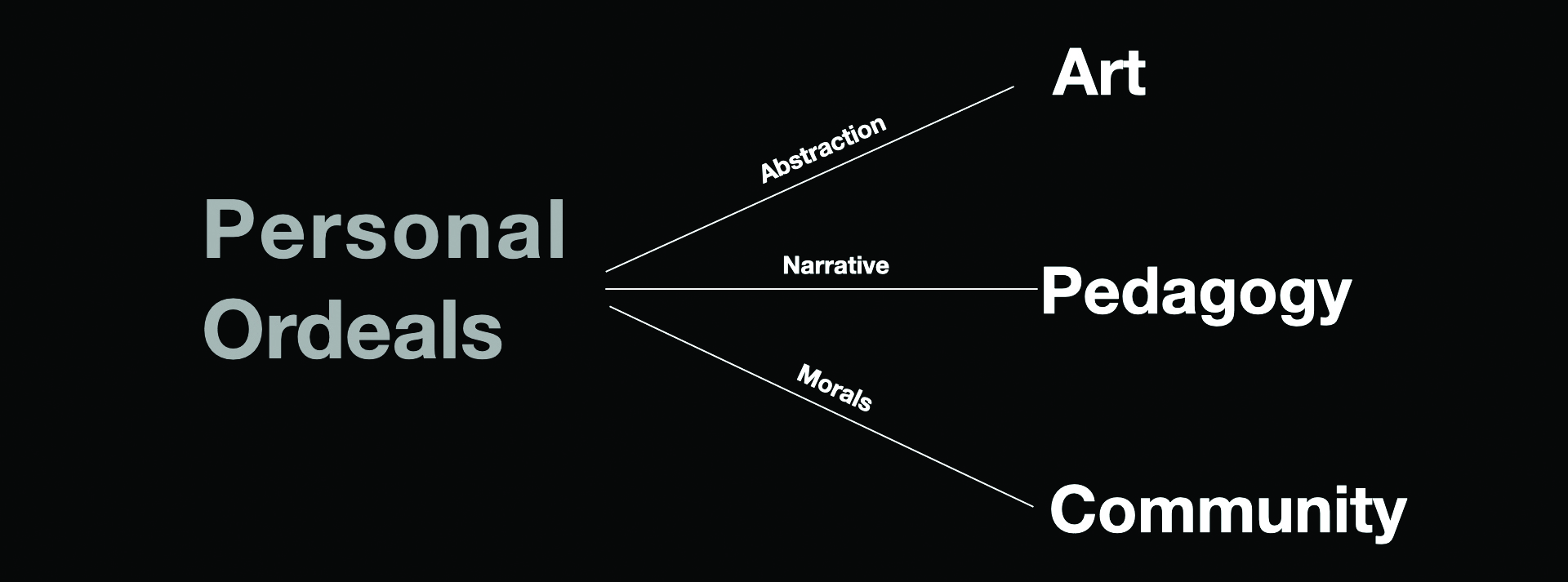

What does this personal ordeal have to do with pedagogy? It is precisely this experience that has prompted me to slow down and investigate my own process of teaching, and, in effect, the local educational processes, where the emphasis on acquiring skills and knowledge has been to match the accelerated development of the country.

There are three key-points I want to highlight from this incident.

1 Empathy in Experience

Emotions are the domain of empathy, and empathy is the backbone of emotional intelligence.3 There is abundant evidence that humans remember events, data and situations better with emotion. This just makes sense. Don’t we recall easily the moments we were happiest in our lives or those when we were grieving? Tyng and colleagues, in a study done in 2017, concluded that “emotional events are remembered more clearly, accurately and for longer periods of time than are neutral events.”4 This suggests that emotions play a crucial role in the higher order mental processing of information, such as problem solving and creativity. Sheldon and Donahue, in 2017, further elaborated on the effect of emotions in the retrieval of memories.5 Another article by the Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) in 2020, stated that long-lasting memories are tied to intense emotions.

Fig.1 Memorable experiences are key to effective learning.

Building memories is therefore indispensable in learning, and vice versa. For us in education, this means our memorable experiences can and should be a take-off point in the delivery of our lessons. We must diversify ourselves so we can have a range of life experiences to use as narratives for learning, because narratives, by their nature, are repositories of our emotions. This does not mean that we just sit in class and tell stories, it means we have to relate our own experiences to the lessons we have planned for the day. We should not dismiss our own life stories as unimportant in our syllabus, rather, we must use them to make our classes more effective (see figure 1).

Empathy is both a tool and a product. We use it to establish rapport and develop more meaningful relationships within our communities. It is also the result of the constant practice of emotional awareness. We use this tool frequently in our repertoire classes when we have to set an existing piece on our students. We teach them, apprentice-style, the choreography, sharing our personal experiences with the piece, describing what we felt dancing a variation (e.g. from Romeo & Juliet).6 Muscle memory and emotional memory become moulded into the dancer through the transference of emotional experiences, enabling them to have a more empathic journey in the performance. We can apply this to contextual subjects as well. For example, if I were a physics teacher, I can use my experience caring for my dad as a narrative to begin a lecture on levers: how to partner and catch humans more efficiently. The excitement and fear of catching or lifting another human being will surely make them remember the lesson for a long time. The class becomes active and empathic to each other’s roles in the narrative.

Giving real-life scenarios is nothing new, but it is important that we revisit this tool especially now when face-to-face learning has become a luxury. Through narratives and the strong empathic connections they make, our students can better appreciate the significance of education in their own lives. We do not teach only skills in school but instill values in our learners, and values are best taught in an authentic setting, which segues to the next key point.

2 Category and Hierarchy of Values

Primum non nocere is a Latin phrase we often use in the medical profession which literally translates to “first do no harm.” It reminds physicians to be always cautious in the practice of treating patients to make their lives better, not worse. In teaching, we can follow the same principle to encompass values we impart to our students. We regard our students as fully healthy and consider their safety first in their physical, mental and emotional states, so that they can reflect and improve on these aspects in our class. In the current educational milieu of emphasising the acquisition of skill and knowledge, values seem to be last in the pecking order of importance, when, in practice, values should underpin the possession of information and skill.

On their website, “Critical Thinking Web,” Drs. Lau and Chan of the University of Hong Kong categorise human values as either personal, moral, or aesthetic. Personal values are those upheld by an individual (i.e. family first, followed by career, etc.). Moral values are governed by social norms of fairness, well-being and so forth, while aesthetics regard the standards of an art.7 In all these categories there will inadvertently be a ranking of importance for every individual. Our roles as teachers become very significant at this point. We become guides for our students to understand what values they have and how they can organise them.

In dance, aesthetic values take the spotlight. We remind our students to train mobility, strength, and stability simultaneously. We should also train their minds and emotions to equally mirror their skills, so that knowledge, skills and values coexist in a singular event.

Fig. 2 Personal ordeals as source of ideals.

We are able to create art by abstracting from our own personal ordeals and, thus, become more cognisant of the values we practice in the management of these life trials while applying them in the lessons we have for the day (see figure 2). Furthermore, the mind is able to form parallels between seemingly unrelated events in our lives. The choice students make between fulfilling a combination’s spatial requirements vs adjusting to the limited space between their codancers is a simple challenge to their moral values. Do they continue moving expansively, even if it means hitting another person? By bringing these issues to their awareness, we let the students realise how their values affect others. By scaling this moral conundrum to an issue of global survival, we can understand how important reinforcing value systems is in academia.

Thus, I invoke the potential of emotions to elicit a better long-term learning response. The grit I had to muster to keep awake for more than 48-hours in the hospital reminded me of my own hard-headedness in pursuing my friends in a simple game of “catch” during my childhood. Do you still recall the story times we used to have in kindergarten or the games we used to play in preschool?

Emotional events colour our lives. We should use them to make our students remember better. My own hospital tribulations made me find ways to create an environment for myself to safely care for my dad. I can transmute this incident in my improvisation class to make the students find ways to create, even in the absence of equipment or spaces they are used to. I can ask them questions that can reveal their hierarchy of values and make them aware if these values resonate with the principles of “first do no harm.” By initiating this dialogue, I prepare them for the consequences that will follow. They will feel the impact of their decisions regarding something as simple as a movement of the hand in a partnering choreography.

At a time of a global health crisis that challenges our morals and attitudes in life, our domain-specific skills become secondary to our ability to categorise and prioritise our values in relation to our fellow humans. It is even more imperative now for us to focus on values education to prepare our students for the resilience and moral rectitude they need to not merely survive but thrive in difficult times. Perhaps the best example of this can be gleaned from highly trained soldiers during wartime. Faramir, speaking of the battle ahead of his company, the Fellowship of the Ring, said, “… I do not love the bright sword for its sharpness, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory. I love only that which they defend [...].”8 This great commander and would-be steward of Gondor extolled the values for which he uses his talents and not the mere display of his combat skills. Freedom, equality, and dignity are only some of the benevolent values that are life affirming, which noble men will die for. But arguably, the most important virtue that will encompass these aforementioned values is empathy. With empathy we become more appreciative of our fellow man’s condition, whether in mirth or in misery.9 It helps us understand each other’s perspective and initiates conversation amidst conflict. Should we not then imbue with these same moral principles the demonstration of skills that we so highly covet in the conservatoire? By narrating our personal journeys and the values they represent, we would have guided our students to educate themselves not only in skill-acquisition but in the ethical decision-making that is required in the application of this skill. In doing so, we prepare our students for whatever trials they will inadvertently encounter in the future within or without the academe. This process is a hallmark of the next and last key-point.

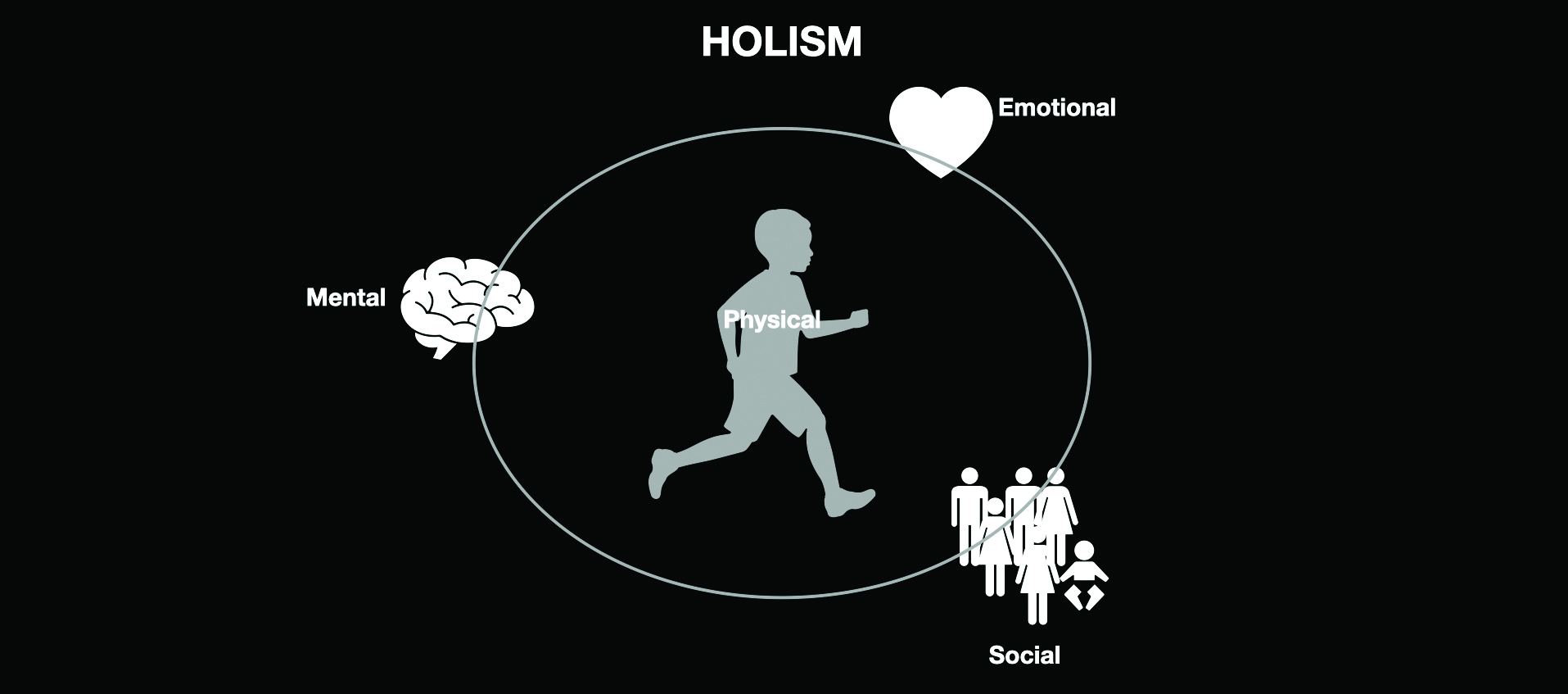

3 Holistic Teaching

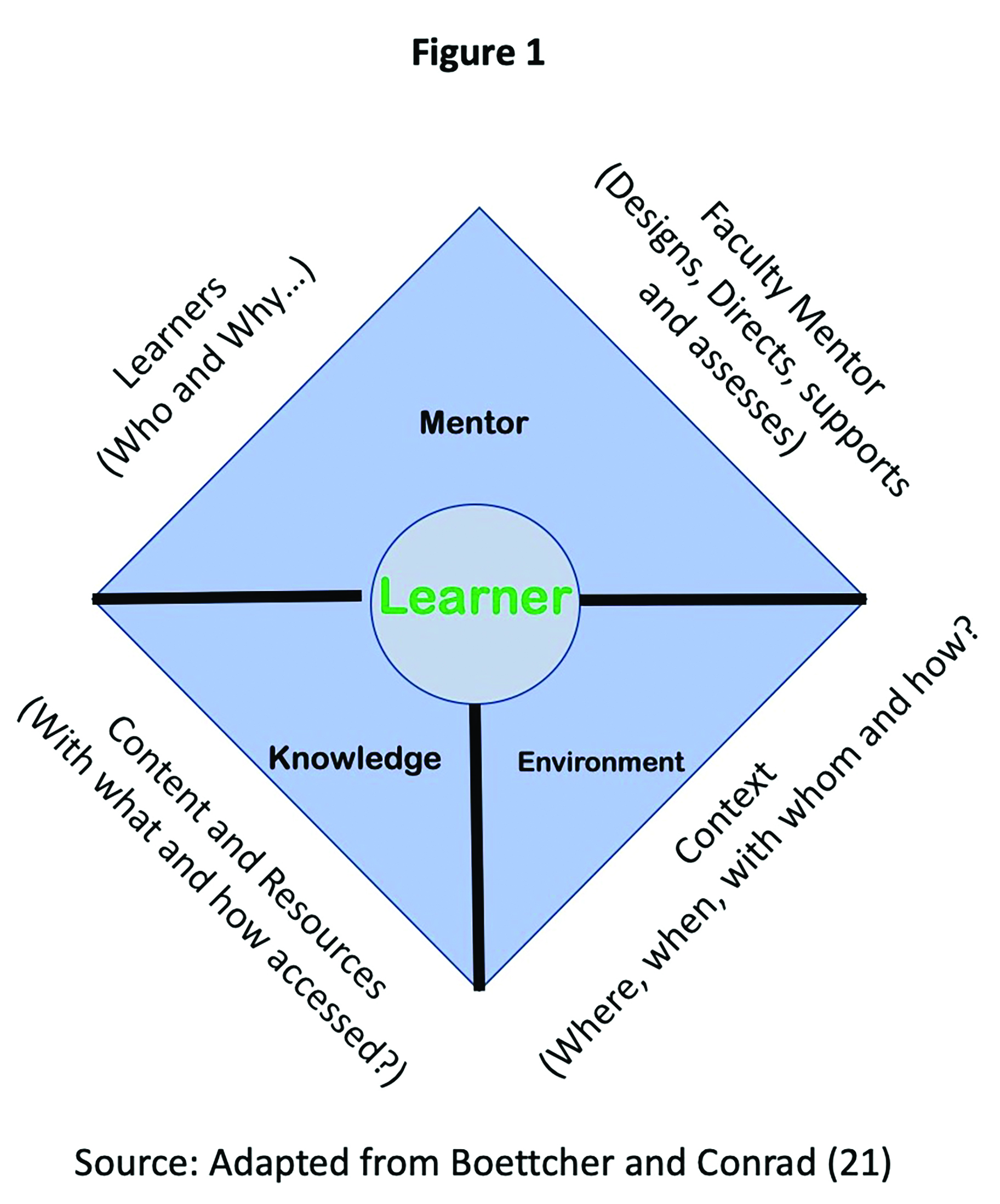

Fig. 3 Holistic Education.

Holism can be traced in the educational systems of the Indian subcontinent and the Greeks.10 The goal of holism is to educate the child to become emotionally, physically, and intellectually a well-rounded individual, contributing to society.11 Singapore has already started to shift its approach to learning by incorporating principles of holistic education in its curriculum, outlining its drive to promote active and healthy living and learning.12 While commendable, its spirit still remains to be truly practiced in the four walls of the classroom, or, in this case, outside of it.

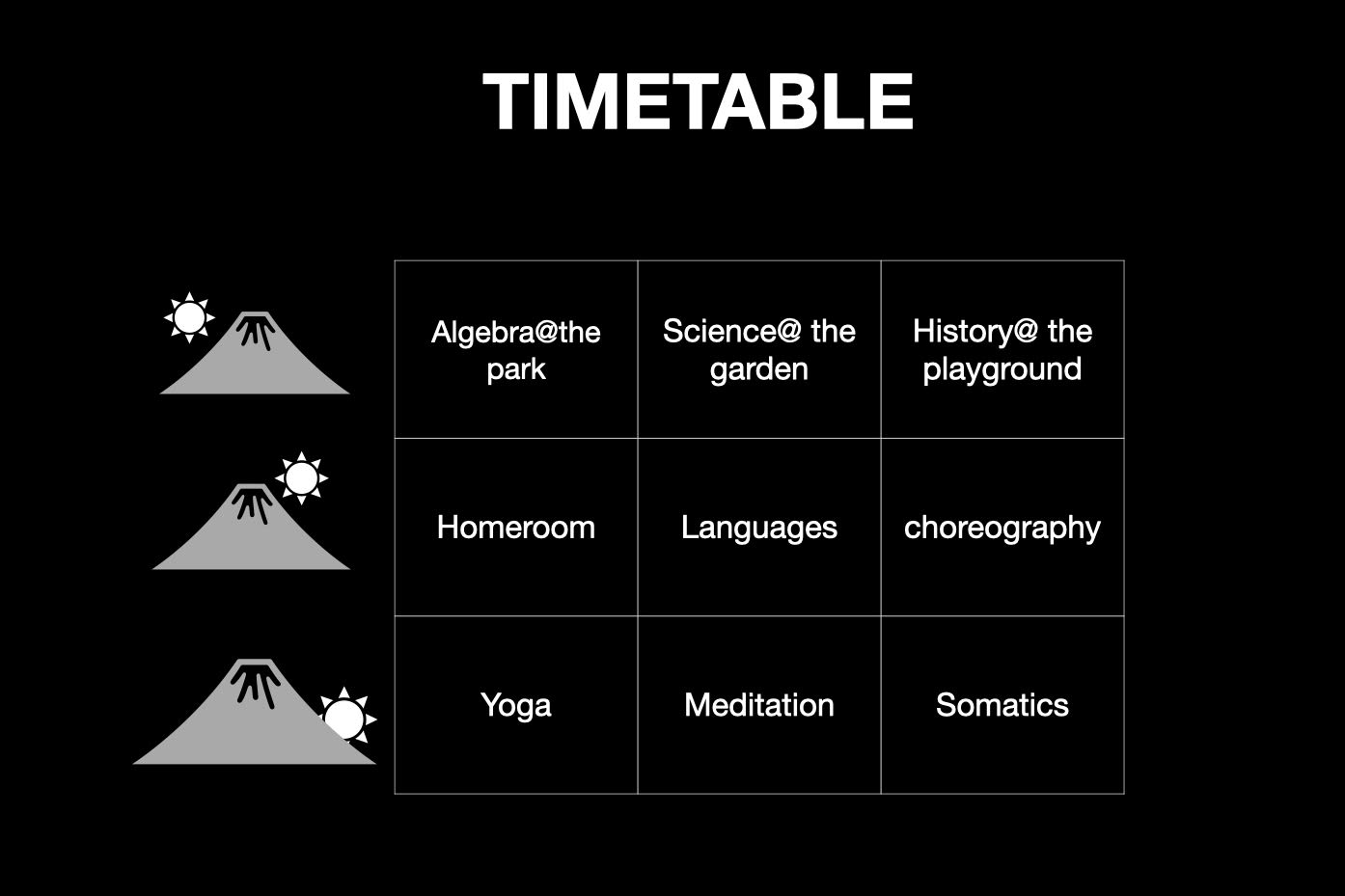

Holism puts authentic learning as the benchmark for education: learning with and in the environment while being physically active, e.g. learning while playing, experimenting, etc.13 Then, how come classes begin in the morning with the students seated in the classrooms passively listening to lectures, when they could be outside following the natural circadian rhythms of human hormones (see figure 3)? An opportune time to exercise is in the morning, when cortisol and growth hormone levels are highest.14Physical education usually is sidelined to the afternoon, oftentimes after lunch when the natural processes of the body is to decelerate, to be able to store nutrients in the liver.15 Should we not then reverse the timetable (see figure 4)? Better still, should we not start training our teachers to teach in the outdoors, to use the playground for their lectures? Learning then becomes both a physical and mental activity. In 2016, the WHO stated that over 39% of the adult population is overweight partly due to poor eating habits and lack of adequate exercise.16 Obesity predisposes us to a variety of illnesses, (e.g. COVID-19). Indeed, there is less reason for us to teach our morning classes seated, than to have them on the playground! In this case, the value of experiential learning is not in its narrative, but in its practice. We allow the whole body to learn physically, mentally, emotionally, and socially. We can achieve this by beginning the day with a physical activity that stimulates critical collaboration (e.g. dance-drama in history class), allowing their bodies to rest and store energy after lunch to focus on more contextually creative and less physically demanding work, and by ending their day with a reflective practice (e.g. somatics).

Seeing our students navigate through the technical, personal and social aspects of their skills throughout the day can help us assess their value systems and make them reflect on these, without going against their normal body rhythms. This whole-body perspective to teaching is empowering to both student and lecturer. In the process of teaching, we can reflect on our own experiences and the emotions that they bring about. It provides us a technique to be aware of our feelings without being overwhelmed by them, so that when we teach through the narrative of our experiences, we may do so with a reasonable clarity of purpose.

Fig. 4 Sample of a holistic schedule.

Unlike in the post-industrial-revolution school setting where we segregate the contextual subjects as a domain of the mind and physical education or the arts as a domain of the body, in a holistic class these domains are integrated in a singular experience.17 Mind, body, emotion, community in one. And we should be able to apply this concept not just in the arts, but in the maths and the sciences as well.

Conclusion

I began this discourse with a narrative, I will similarly conclude.

On the fifteenth day of my quarantine in Singapore, I noted my resting heart rate dip to 52 beats per minute. I still have a dancer’s heart. The solitude and the challenges I recently faced in the hospital made me slow down and recall my own learning journey as an aspiring physician: being thrown into the ER and the clinics, applying what we have learned from the lecture halls. What I remembered most were the times I had to face the patients: delivering babies, inserting intravenous lines, being guided by our senior doctors. But 2021 found me on the opposite side of the fence, I became a patient (or, at least, the caregiver). It made me empathise more with those who sought help from us. It reinforced the concept that the best types of learning are those we carry on throughout our lives—the most memorable ones being those which have triggered strong emotional responses from us.

Like the food that nourishes our bodies, emotional information needs to be processed to ensure its effective delivery and safe application. Our food does not go directly from our mouth into our cells, because the molecules need to be packaged first before they can be utilised in the target organs, so does the information we give our students. Knowledge becomes more easily accessible and useful if it is wrapped in the events of our own life narratives. This does not mean that all our classes need to be sweat-inducing endeavours, but it means that we take the students away from their chairs and on their feet more, to be quick and active in learning.

Fig. 5 Somatic movement to end the day.

The ideas presented here are perhaps already inherent in our daily pedagogic practice. I am simply bringing awareness to these processes so that we may properly utilise them in our classes and make the most of the learning journey of our students.

My personal travails have made me realise that there must be some overhaul in the way we teach and how we schedule our lessons for this well-rounded approach to education to happen.

We can slow down to tell our own stories to derive quality information from them by: starting the day with physical activities inspired by narratives; allowing the body to go through the natural processes after lunch to focus on more contextual problem-based work as their bodies store fuel; ending the day with a method for self-reflection and wellness (see figure 5). We would have then transformed our learning spaces into a microcosm of the real world, making our instructions more empirical and humanistic in the process. In this way, we engage our students holistically and empathically through the values we have shared from our own life experiences.

Footnotes

1 Won et al.

2 Dayrit xxi

3 Goleman

4 Tyng et al. 17

5 Sheldon and Donahue 740

6 Prokofiev

7 Lau and Chan

8 Tolkien 608

9 Agosta

10 Miller 1

11 Hare 3

12 Ministry of Education Singapore

13 Loveless

14 Ducharme

15 Drayer

16 World Health Organization

17 Krishnan

References

Agosta, Lou. “Empathy and Sympathy in Ethics.” The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. iep.utm.edu/emp-symp.

“Sinus Bradycardia.” Cedars-Sinai Health Library, Cedars Sinai, 2021, https://www.cedars-sinai.org/health-library/diseases-and-conditions/s/sinus-bradycardia.html.

Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “Why Are Memories Attached to Emotions so Strong? -- ScienceDaily.” ScienceDaily, 13 July 2020, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/07/200713144408.htm.

Dayrit, Manuel, et al. “Health Systems in Transition: The Philippines Health System Review.” The Philippines Health System Review. Edited by Walaiporn Patcharanarumol and Viroj Tangcharoensathien, vol. 8, No.2, World Health Organisation, 2018, pp. xxi–1.

Drayer, Lisa. “Are ‘Food Comas’ Real or a Figment of Your Digestion?” CNN, 3 Feb. 2017, https://edition.cnn.com/2017/02/03/health/food-comas-drayer/index.html.

Ducharme, Jamie. “This Is the Best Time of Day to Work Out, According to Science.” Time, 27 Feb. 2019, https://time.com/5533388/best-time-to-exercise/.

Goleman, Daniel. “What People (Still) Get Wrong About Emotional Intelligence.” Harvard Business Review, https://www.facebook.com/HBR, 22 Dec. 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/12/what-people-still-get-wrong-about-emotional-intelligence.

Hare, John. “Holistic Education: An Interpretation for Teachers in the IB Programmes.” International Baccalaureate Organization, 2010. https://kirrawatt.com/uploads/2/4/7/2/24720749/holistic_education.pdf.

Lau, Joe, and Jonathan Chan. “[U01] Three Types of Values.” PHILOSOPHY@HKU, 2021, Critical Thinking Web https://philosophy.hku.hk/think/value/values.php.

Loveless, Becton. “Holistic Education: A Comprehensive Guide.” Education Corner© Online Education, Colleges & K12 Education Guide, Education Corner, 2021, https://www.educationcorner.com/holistic-education.html.

“Our Students.” Ministry of Education Singapore, Ministry of Education, www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/our-students. Accessed 6 June 2021.

Prokofiev, Sergei. Romeo and Juliet. choreographed by Ivo Váňa-Psota. Performed by Ballet of the National Theatre. 1938, Mahen Theatre, Brno.

Sheldon, Signy, and Julia Donahue. “More than a Feeling: Emotional Cues Impact the Access and Experience of Autobiographical Memories.” Memory & Cognition, no. 5, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, Feb. 2017, pp. 731–744.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Lord of the Rings. Res. ed. of 2002, EPuB ed., Great Britain, Harper Collins, 2009.

Tyng, Chai M., et al. “The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory.” Frontiers in Psychology, Frontiers Media SA, Aug. 2017.

Krishnan, Karthik. “Our Education System Is Losing Relevance. Here’s How to Update It .” World Economic Forum, 13 Apr. 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/our-education-system-is-losing-relevance-heres-how-to-update-it/.

Miller, John P. “Ancient Roots of Holistic Education.” Encounter, vol. 19, no. 2, Summer 2006, pp. 55–59. EBSCOhost, https://search-ebscohost-com.libproxy.nie.edu.sg/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eue&AN=21723989&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Won, Jun Hee, et al. “Risk and Mortality of Aspiration Pneumonia in Parkinson’s Disease: A Nationwide Database Study.” Scientific Reports, no. 1, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, Mar. 2021, p. 1.

“Obesity and Overweight.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization. 9 June 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

Essays

Introduction

Music is often seen as a form of personal expression. A listener may comment on the way a piece of music touches them, or perhaps suggest that there is something in a performance that seems genuine or authentic. At other times such observations take the form of a simple preference for one artist over another, citing a variety of reasons for these choices. In each of these scenarios identity, “an essence signified through signs of taste, beliefs, attitudes, and lifestyles,”1 may be seen as the driving force behind such reactions. When an individual perceives some point of commonality or alignment with someone else, there is a sense of connection. Identity is a central force in every aspect of our lives; from clothing choices to the quality and nature of interpersonal relationships, much of our experience is influenced by the features which we view as our own defining characteristics and the points at which they overlap with the defining characteristics of another.

As a concept, identity is multifaceted, with a variety of definitions and theories drawing on a wide range of disciplines. This paper is informed by my own experiences and observations teaching music at a tertiary institution, coupled with an examination of a range of sources addressing student experience and identity formation, particularly those which adopt positions grounded in anthropology or social psychology. Steph Lawler suggests that identity is best understood as a series of “ongoing processes’’ rather than a simple “sociological filing system.”2 The focus on the ongoing process of identity negotiation necessitates an approach grounded in social psychology, which takes into account the way in which “social identities might differ in the functions they serve.”3 Kay Deaux suggests that seven such functions exist, many of which are prominent in university life, including self-insight, social and intergroup comparisons, and social interaction.4 A similar premise is suggested by James Cote and Charles Levine, who propose a three level approach to identity analysis, focusing on society, interaction, and personality.5 Building on this, I suggest that a key concept relating to identity formation and communication is that of value, specifically the interplay between individual and collective values. For this reason, the discussion that follows is based upon Herbert Blumer’s model of symbolic interactionism, which suggests meaning is determined by both personal experience and social interaction, and it is this sense of meaning which determines how an individual will act towards something.6 Identity, then, may be seen as a collection of constantly evolving characteristics formed through the interplay of personal experiences, values, and social interaction, leading to a sense of self and belonging based on perceived shared values with a social group. Once established, this sense of identity will continue to evolve over time, and will be revealed to others to a greater or lesser extent as a result of a conscious act of curation on the part of the individual.

This article seeks to explore the ways in which tertiary music students form and develop a deeper understanding of their own unique identities, and how students may be encouraged to reflect upon and engage with this process. It focuses on the exploration and development of identity in the training and education of musicians within a higher education context. Following a brief introduction to identity in music, the discussion will move on to the processes of identity negotiation within higher education. Some of the factors influencing this process will be examined, both in ‘normal’ times and within the ‘new normal’ of the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated restrictions. This will lead to a discussion of the way these have impacted the way in which students understand and explore their own identities. Following this, a number of recommendations will be presented, with accompanying examples from my own experience teaching critical thinking and contextual studies to tertiary music students, to suggest potential responses to some of the challenges faced by students today, while maintaining a non-prescriptive approach to these interventions, which can and should be tailored to fit individual context. Overall, the aim is to reassert, or perhaps reinforce, the importance of a focus on identity development in the training and education of performing artists.

Identity in Music

In his discussion of Portuguese fado music, Richard Elliot puts forward the suggestion that:

the music is about the people [audience] themselves, but they desire to see others [performers and named individuals] representing them wishing to see themselves represented by those privileged, highlighted and floodlit actors[…] the request for representation of the community […] comes from within the community itself.7

Although his remarks referred to one specific form of music, it could be supposed that it is this need for representation which first gave birth to numerous other genres, whether the desire is for representation of the individual, the community, or the emotions experienced by these entities. This sense of connection via shared experiences or beliefs is the foundation of communities, and is inextricably linked with the notion of individual and collective identity. While there are other factors contributing to perceptions of and preferences for one artist over another, such as technical execution or particular aesthetic qualities, one only needs to look at media coverage to realise the amount of value placed upon the identities associated with individual artists. It is, in fact, identity which is often the mediating factor connecting performer and audience. As such, I suggest that an awareness and focus on identity should be seen as a vital component of any form of professional education or preparation for musicians.

However, just as musical skill and commercial success do not manifest overnight, neither is an identity born fully formed, in the spur of the moment. Given the amount of time devoted to the development and honing of these abilities, and the centrality of identity to every human interaction, it is necessary to understand the ways in which identity may be negotiated and developed by an individual. Furthermore, as the focus of this paper is the experience of undergraduates majoring in music, it is necessary to understand the particular way in which identity can (or may) be nurtured, formed, and communicated as part of the training received by every music student.

The Impact of COVID-19

The past two years have seen the emergence of a new challenge to identity negotiation. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated a radical change in the way everyday tasks are approached, and this has been particularly significant within educational institutions. While the situation has evolved since the early days of the pandemic, and many universities are moving towards a more stable situation in which administrators and educators are able to plan and act, rather than implement the hurried reactions that were required in the early days of the crisis, the limitations and effects of the various precautionary measures are still prominent forces, and at the time of writing the situation is still unfolding. New forms of digital media and technology have quickly become ubiquitous, with terms such as ‘Zoom’ receiving new definitions in the Oxford English Dictionary.8 In many ways, disruption has been kept to a minimum, with the rise of home-based learning apparently seeking to prevent the worst of the losses for students.

However, despite living in an age of increasingly sophisticated technology, the effects of a sudden switch to a model of education and interaction which is predominantly digitally mediated are still significant; not only for content delivery and skill development, but also for the ongoing process of identity negotiation, “in the digital age, where students spend much of their time online, identity is […] moderated by their experiences in the online environment.”9 The sudden shift to online modes of teaching and learning, even when delivered synchronously, have undoubtedly had an effect on the experience of tertiary education. While the present paper does not seek to evaluate the effectiveness of online or blended learning approaches for teaching purposes, other elements of university life have taken a significant hit.

With a move away from face-to-face classes and campus life, social interactions no longer take into account notions of proximity. While it may be argued that there have long been forms of interaction taking place at a distance, whether through letter writing or telephone conversations, this is the first time in history that such distance has become the norm, with social interactions now entirely dependent on just two senses. This is further compounded by a drastic reduction of spontaneity. Whereas once students might have bumped into one another on campus, during the worst of the pandemic these third spaces were empty, depriving students of the opportunity for impromptu interactions, revelations, or genuinely organic encounters with fellow students or teaching faculty. Increasingly, social interaction takes place by schedule, with both parties consulting their timetables before agreeing on an appointment for a video call.

The effects of this may vary from student to student, but as interactions become more limited, whether due to digitally enforced distance or the visual barrier of a mask, it becomes harder for individuals to relate to one another or understand one another. Students may, therefore, feel less certain of their own identities because they are less confident in their perception of others. Many interactions depend on a certain level of comfort and familiarity, which is built up over time and enables honest and open exchanges of ideas and sharing of experiences. Where that comfort is uncertain, these exchanges become more heavily and consciously curated, which in turn limits opportunities for exposure to alternative perspectives or for a respectful challenge of beliefs. This can result in a much narrower view and range of experiences, comparatively speaking, while potentially limiting the opportunity for artistic, intellectual, and personal growth.

Identity in Tertiary Music Education

One of the key assumptions underpinning this paper is the notion that a decision to study music at university level cannot, for most students, be written off as a purely pragmatic choice. It is likely that most music students see the value in such a course of study beyond simply that of obtaining an academic qualification, and as such they might wish not only to learn, but to develop and grow within their chosen field. This implies a certain investment in the discipline and an inclination to view music as a part of their personality. To put it another way, music goes beyond the ‘doing,’ and is a significant factor of the students’ ‘being.’ In a study focusing on the link between identity formation and academic motivation among university students, Faye and Sharpe suggest that, “a sense of identity leads to intrinsic motivation in part because it provides university students with a solid base on which to build an enduring sense of self.”10 They argue that this is due to the motivational process which involves the individual seeing value in an activity because they are able to make it a central part of self. The study goes on to suggest that “a strong sense of self affects intrinsic academic motivation because a strong sense of self affects feelings of competence,” which in turn contributes to the development of a connection between personal and professional identities.11 In this way, a student who can form this kind of relationship between themselves and their own music is able to engage in a cyclical process of development in which identity feeds motivation, which in turn increases competence, and this reinforces the sense of self and identity.

It should not be assumed, however, that the development of identity is entirely determined by individual actions. Rather, identity is perceived, at least in part, as it relates to a wider sense of place and belonging in relation to others. Reed and Dunn draw upon a number of studies to suggest that “a sense of belonging in [higher education] relies on the development of connections and relationships with peers through positive social engagement and support.”12 Building on Blumer’s symbolic interactionism, identity may be seen as interpreted and developed not in isolation but viewed in comparison with (or perhaps in opposition to) lived experiences within society. In his examination of identity formation among undergraduates majoring in music education, McClellan defines social identity as “the portion of an individual’s self-concept derived from perceived membership in a relevant social group.”13 He goes on to cite Dolloff’s account of the identity formation process, suggesting that “we construct a dynamic and evolving sense of who we are through our experiences and relationships to our environment, others, and the results of our actions.”14 The role of social interaction within the process is further emphasised through the suggestion that individuals choose to become members of certain cultures, after which they work to become familiar with the prevailing cultural norms and practices in order to shape and contribute to the cultural production of the group, and through this conscious act of identifying with a certain group, this membership becomes assimilated into the identity of the individual.15 In this way, an individual is able to form a personally meaningful sense of identity based on a sense of belonging within a group they have chosen, which in turn is validated through active involvement and contribution. This results in a situation in which the individual does not simply feel as if they chose to join the group, but that they are bringing value to, and enriching, the group through their membership. However, when these social interactions are altered, impeded, or disrupted, there are potentially negative consequences for an individual’s sense of self or identity. As such, it is important to recognise some factors which affect identity formation, both under normal circumstances and as they exist during the pandemic.

Factors Affecting Identity Formation

While the process of identity formation is an ongoing one, with each interaction contributing something to a student’s sense of self and sense of belonging, the journey is not always a smooth one. While there may be occasional turning points—key moments in which a particular student is forced to re-examine certain beliefs they may have about themselves—these tend to vary from one individual to the next. There are, however, certain factors which may complicate the process of identity negotiation, or in some cases create a situation in which the need for such a process is heightened.

Transition Process

The first of these obstacles is encountered at the very beginning of the university experience. In their examination of identity formation among students transitioning to university for the first time, Scanlon et al. argue that identity is closely linked with context, and that the massive change in context precipitated by this transition “may result in feelings of loss, of ‘displacement’, and subsequent identity discontinuity,” which in turn requires the individual to re-negotiate their identity within this new context.16 This situation is exacerbated, they argue, by students’ reliance on former experiences and knowledge from prior educational and practical experiences, which does not correspond with the reality of university life, and as such did not fully prepare them for the identity shift that would be required.17 Students entering university for the first time, then, find themselves in a situation in which they must relearn many of the habits and behaviours they had previously relied upon. Faced with the opportunity to start a new chapter of their lives, this transition period is critical. For many, this is the first educational experience in which they are able to exercise complete freedom of choice, selecting not only the subject they wish to study, but also the institution and, by extension, the culture into which they are entering. Furthermore, with some exceptions, this process takes place at the onset of adulthood, with each student able to draw upon a growing range of life experiences with greater maturity and self-awareness than any previous new beginning.

While the specific details of an individual’s transition experience will be largely affected by the prevailing COVID-19 restrictions and guidelines in different parts of the world, the pandemic has undoubtedly affected this process. Some of the more obvious examples of this include online classes, which may sometimes be delivered asynchronously, limits on group sizes, and restrictions to social activities. The significance of these changes are magnified, however, by the fact that there has been no precedent for this new type of university experience. Students are no longer transitioning to a lifestyle they have seen depicted in popular media, or have heard of from acquaintances, but are faced with an entirely new situation. While certain elements, such as the role of assessment, may remain stable, many other experiences are either filtered or diluted as a result of health risk requirements, or in some cases changed entirely.

Role of Socio-Economic Status and Social Capital

For all the free agency experienced by new students, however, there are still some factors already in play over which they have little to no control. When considering factors which may facilitate or hinder the development of identity for students in higher education, Jensen and Jetten highlight the role of socio-economic status. They suggest that students entering university from backgrounds of higher socio-economic status (SES) have an advantage due to greater social capital, which they claim, “forms an important building block for the development of these identities in higher education.”18 Social capital, in this context, is defined as “the value derived from membership in social groups, social networks or institutions. Such membership gives individuals access to resources and collective understanding.” They do clarify, however, that opportunities to form new social capital during a student’s time at university will arise.19 Despite these opportunities, it stands to reason that those students with greater social capital at the outset are likely to experience an advantage when it comes to identity formation, particularly in the early days and weeks of their course of study.

The importance of these early interactions for the formation of identity cannot be overlooked. Beyond the adage about only getting one chance at a first impression, the shift in mindset and behaviour required when first entering tertiary education can be a jarring shock to the system. The obvious changes include increased levels of independence and responsibility, higher academic standards and expectations, and in many cases even a geographical shift.

Jensen and Jetten’s investigation into social capital also highlighted the importance of two main forms of social interaction with relation to identity formation—bonding interactions and bridging interactions. Bonding interactions are those which take place between socially homogeneous groups, such as students undertaking the same course of study, whereas bridging interactions are those involving diverse individuals, illustrated in this study by interactions between students and lecturers. While presenting both forms of interaction as valuable opportunities for identity formation and development, their findings suggested that many students prioritised bonding social capital, which contributed to a sense of communal identity and stability through the strengthening of mutual support networks. However, the authors note that this can, at times, hinder students from seeking bridging opportunities either with students at higher course levels or with educators. As the students became more confident and established in their sense of shared identity, they were less inclined to seek connections beyond those groups, preventing them from forming new relationships and potentially missing out on opportunities for further academic and professional identity formation.20

The importance of such varied social interactions was also apparent in the findings of McClellan’s investigation into identity among music education majors. He lists a number of examples, including “undergraduate interactions with peers, music professors, music education professors, and ensemble directors in ensemble rehearsals, applied lessons, class meetings, and social settings in the music department,” all of which reinforced students’ self-concept.21 This self-concept will form the basis of any self-perception of identity, which in the context of the music student, will ultimately play a part in the formulation and presentation of current and future artistic identities. The link between social capital and identity is further emphasised by James Côte who suggests that “social capital networks activate relational aspects of identity.”22

With regard to social capital, COVID-19 has caused two major disruptions. A full discussion of the first, which is the financial impact upon individuals and organisations, is beyond the scope of this paper, although this will certainly have been felt by students and their families who are facing financial restrictions, which at times necessitate a withdrawal from programmes of study. Beyond the economic effects, new measures have also placed restrictions upon social interactions of various types, thereby hindering efforts at bridging interactions. While this may change as regulations and recommendations are eased, in the early days of the pandemic interpersonal exchanges adopted a more formalised nature often taking place at a distance within the framework of digital communication software. This lack of proximity and spontaneity results in relationships and common understandings emerging much more slowly, which by extension affects the growth rate of any social or professional networks. Beyond the effect upon interactions between peers, this also feeds into the nature of interactions between students and faculty.

Interactions Within the Institution

Having now entered the tertiary institution of their choice, students find themselves in a situation where their concept of self-identity is potentially less stable than ever before, yet more important than ever. Depending on the nature of the institution and the students’ prior experiences in the education system, it is quite likely that this is the first time a student may find themselves in an environment in which they can devote themselves almost entirely to the pursuit of a single discipline, such as music. Additionally, they are working and learning alongside an entire community of supposedly like-minded individuals, sharing the same passion and devotion to a subject. And yet, such a situation is not without its challenges. The student becomes aware that they are about to spend several years among people they have never met before. Add to that the fact that seeing so many other practitioners of the same art up close can often cause the small differences in ability and understanding to block out the larger commonalities that bind and unite. While not without opportunity, it is easy to understand the reasons why Scanlon et al. describe the transition to university as a “loss experience.”

The role of interactions with academic staff, in particular, was emphasised by Scanlon et al. who found that a major challenge for new students was rooted in their concept of the identity of the teacher. Previously, they suggested, teachers were simultaneously friend, confidante, supporter, and someone who developed a personal relationship and understanding with each student, visible as both professional and social beings. However, university lecturers and professors were seen as the antithesis of this—distant figures who saw each student as a number and as one face among many, “when students feel that they are only a number and the lecturer is no longer a friend, then they suffer identity displacement and a sense of loss for past learning situations.”23 They suggest this is made worse in environments where gaining physical access to the lecturer seems to be difficult. They clarify, however, that rather than pointing a finger of blame, this difficulty arises out of mismatched expectations: “students are not aware that lecturers are working within a neo-liberal set of practices and are struggling in many cases to develop a more research-based identity and so have less time for students.”24 Nevertheless, this perceived distance between learner and teacher can become an impediment in the student’s desire to relate to, or identify with, influential industry practitioners.

The various demands upon educators’ time and attention has only increased since the start of the pandemic. While most institutions have now moved beyond the initial rush of reactions to the virus, the process is nevertheless an ongoing one, with changing regulations leading to a desire to pre-emptively adapt courses and teaching materials, preparing for both digital and physical modes of delivery. Beyond this, many departments have recognised the need for heightened levels of pastoral care for students navigating the uncertain landscape. Similarly, there are fewer opportunities for impromptu exchanges between staff and students, either due to the emphasis on reduced proximity and face to face meetings or the use of online platforms which may discourage the former practice of students grabbing a moment with the lecturer after a class, to either ask for clarification or share a point of interest.

Identity Curation and Communication

While the processes discussed above may be referred to as identity formation or development, a more accurate term would be identity negotiation. This is a multifaceted process which involves not only discerning and establishing the various elements of an identity, but also places emphasis on the way that identity is presented and communicated. Swann and Bosson argue that this goes beyond simple self-presentation, which they define as a set of tactics designed to achieve interaction goals, but seeks a balance between fulfilment of interaction goals and fulfilment of other identity-related goals such as independence or coherence.25 Nevertheless, as in any other form of communication, consideration must be given not only to what is to be communicated, but also how it is communicated, how it is received, and how it is perceived. When the message being communicated is an individual’s identity, this may be seen as communicating signs of unity or individuality. This communicative aspect of identity is highlighted by Thomas Turino, who dismisses the idea of complete unity within cultures or social groups. Rather than seeing identity as a fixed set of characteristics or behaviours for each individual, Turino emphasises the importance of recognising “how individuals within the same society group themselves and differentiate themselves from others along a variety of axes depending on the parts of the self that are salient for a given social situation.”26 In this way, the individual negotiates the balance between the various elements of themselves and the needs of any given situation or interaction.

Turino suggests that a clear conception of the self and individual identity is vital for any examination or discussion of expressive cultural practices. Importantly, he distinguishes between the concepts of self and identity, due to the differences in the way they function.27 The former, he argues, incorporates all aspects of the individual, including beliefs, habits, and behaviours, whereas the latter consists of a partial selection of habits and behaviours, specifically chosen for a given situation in order to represent oneself in a particular way.28

In this way, I propose that the communication of identity may be viewed as an act of conscious curation. The individual must consider what they choose to reveal in any given situation and to whom they reveal it. While I do not suggest any individual retains total control over the way in which others see them, this process nevertheless allows the individual a significant amount of curatorial influence. Just as a celebrity may keep elements of their personal life out of the public eye, so too does each individual construct multiple personae depending on the particular arena or social setting in which they find themselves. Each of these personae is carefully crafted to allow the individual to attain a certain end. These goals may be positive, in the form of achieving a certain goal, or may be more defensive in nature, such as maintaining a façade as a form of emotional protection. In this way, identities are constantly negotiated, providing room for growth and development while allowing the individual to retain control.

This curatorial act has become more prominent during the pandemic, largely as a result of an increase in digital communication. Students and educators alike are now able to decide not only how much of their face is seen on camera (or in some cases whether to turn it on at all), but also the context in which they are seen through the use of virtual backgrounds. Decisions regarding clothing choices are regulated by how much is visible on camera, and the mute button prevents the majority of comments and reactions reaching other students. While there are potential benefits to this enhanced ability to control the way one appears to others, the flipside is that this brings about fewer opportunities for individuals to perceive or understand the nuances of social or educational situations and norms.

Recommendations

The discussion so far has established that identity can be seen as a crucial part of the university experience and that it is a particularly important factor in the training and preparation of musicians. Undergraduates majoring in music will face frequent challenges and obstacles as they negotiate their identity, and the recent pandemic has only made this situation more challenging. Just as it is foolish to continue doing the same thing while expecting a different outcome, it has become clear that the new circumstances necessitate a different approach, not just to obtain a different result, but even to achieve the same outcome as before. Educators need to be sensitive to this process of negotiation and should provide opportunities to support students wherever possible. Below are some recommendations which may help facilitate a greater focus on identity among students. Each recommendation will be accompanied by a personal example of the way in which they have manifested in my own teaching practices while teaching modules focusing on contextual studies, critical thinking, and research to tertiary music students. These examples are intended to highlight just one possible application of these principles in my own context. As with all approaches to teaching, factors such as student and teacher personalities, needs, objectives, and institutional regulations should be the guiding principle. It should also be noted that while many of these approaches have come about during a time of pandemic, there is much to be said for continuing the emphasis on supporting student identity development beyond the current situation.

Interactions with Faculty

The role of social interaction in cultivating identities has already been established above. However, it should be remembered that this refers to any interaction between individuals and these can be particularly powerful when they take the form of a bridging interaction, such as an exchange between student and teacher. Scanlon et al. reported multiple findings that suggest students value such interactions highly, while feeling a sense of loss and anonymity when these connections are missing or lacking in some way.29 Similarly, Linda Dam warns that digital content delivery may lead to a sense of isolation among students due to a perceived lack of contact and interaction with faculty, especially when classes are delivered asynchronously.30 While there will always be professional boundaries, and of course lecturers are entitled to the privacy and control that comes with curation, an appropriate level of openness and familiarity is often welcomed by students. This is particularly beneficial in subjects such as music where many faculty members possess not only academic credentials, but also professional industry experience. As such, they will often be seen as figures occupying roles and having accumulated experiences which are an object of aspiration for their students. In this way, the lecturer is not simply an educator, but an example; they become role models and, as such, there is great value in students recognising such figures as relatable people, representing attainable goals.

In general, it is reasonable to assume that the majority of students pursuing further study in a subject such as music chose this path not only on the basis of some level of skill or ability, but also out of a genuine interest and passion. As such, they look not only to their peers, but also to their lecturers. Their past experiences have taught them that teachers can be accessible and, even when this may not seem to be the case, many students will often persevere, seeking not only information or education, but points of connection. While educators are by their nature in positions of authority they are also seen as experts in their field and this expertise lends credibility to their experiences and opinions, which may lead to a perceived value placed upon such thoughts.

I saw this for myself during an online class with some first-year diploma students. It was about half way through the first semester of their studies and, despite teaching them on a weekly basis, we had yet to have any face-to-face interaction. After a student made a passing reference to the value of ‘world music,’ I suggested that, if we are to engage fully in critical thinking, we should be prepared to question such terms as surely all music comes from somewhere in the world. The student sent me a private message asking to discuss it further after class and remained online for almost half an hour just to ask questions and share opinions.

What comes across as friendliness or inquisitiveness may actually be a manifestation of a search for commonality. By engaging in conversation about a topic that interests them, the student may be trying to build a sense of connection. This is not simply to regain the friendly teacher figure they knew from school, but is an act of engagement with someone whose position identifies them as a representative of a professional community. By choosing to study a specific major, the student is either indicating an aspiration to be seen as a member of that community, or is already identifying with it. Either way, this easily overlooked conversation is a conscious act of identity formation, in which the student is seeking validation or affirmation, looking for points of similarity that suggest or reinforce a sense of belonging.

Assessment

Beyond personal interaction, other areas of the students’ learning experience can also be considered when looking for opportunities to encourage greater exploration of identity. Formative and summative assessment tasks, for example, are ripe with opportunity for students to explore what matters to them—whether this is a critical reflection on a performance, a journal relating to the classes undertaken in the course of the module, or even a task such as writing a blog post on an issue in which they have some sort of investment. Feedback, similarly, should validate and encourage this form of reflexivity. One of the most fruitful activities that came out of a recent module was when I asked students to write and share an artist statement. This not only required students to think in the abstract, but to engage with how they saw themselves and how they wished to be seen. Without exception, every student engaged in this activity and shared elements of their professional journey and identity. The lasting effect of this activity was revealed in the final assessment for the module, which was a reflective journal, in which a number of students made reference to either the specific activity or the process. Of course, academic and intellectual rigour can be encouraged and developed, but it should also be remembered that even academic research, at least within the arts, relies on a series of interpretations of ideas or evidence, with every interpretative act shaped by personal bias, beliefs, and experiences, all of which are tied inextricably to a sense of identity. While these interpretive acts are generally carefully considered and well-informed, the subjective nature of artistic research is such that the identity of the individual will always play a part.

Establishing Sense of Community and Multiple Levels of Interaction

While the digital medium may be seen as filtering out some of the more interactive opportunities of the physical classroom, it is still possible to encourage identity negotiation when using digital platforms. Rachel Toor offers some suggestions for establishing a sense of community and building relationships in the context of classes taking place over Zoom or other synchronous video platforms. She emphasises the value of this, acknowledging that “students want to be seen, to know that we care about them, to be reminded that we understand that they’re struggling.”31 While some of the suggestions made are intended to simplify logistics, many of the approaches serve to promote interaction among students, and between student and educator, encouraging engagement and participation within the bounds of each students’ comfort level. One such strategy is making use of breakout rooms for small-group activities. This has an empowering effect on students, particularly those who may be reluctant to draw attention to themselves by speaking out in a larger group setting, while giving them the chance to make their voices heard. With the provision of this opportunity, students are encouraged to see their ideas and experiences as valid, allowing them to see themselves as contributing members of a society or group.

Another strategy suggested by Toor involves the use of the text-based chat box. Much like the breakout room activity, this offers a platform for students to respond and contribute without fighting to be heard over more dominant voices. She suggests that this approach adds an element of fun, particularly when students feel able to go beyond simply responding to questions and are free to react and converse with one another, much as they would when physically together.32 There is much to be said for this kind of interaction as, beyond lightening the mood, it once again reinforces that sense of camaraderie common to shared membership of a social group. Taking this further, the chat box becomes a vital tool in the process of identity curation. Not only will it allow for the free and spontaneous reactions and responses that come with familiarity and comfort, it also offers students a chance to carefully select their words, crafting the message before hitting send in an act of self-reflection, simultaneously maintaining and communicating the identity they wish to be known. At times this may take the form of a carefully thought-out response to a question, other times it may be words of encouragement following another student’s presentation. Beyond communication, the chat function also offers a way of protecting image and identity with the use of private messages, such as a request for clarification from a student who does not wish to be seen as struggling to understand, or a thoughtful or insightful response to a question from a student who wishes to be seen in a particular light. By offering students this way to contribute, I have seen increased engagement from many students, including those who are usually reluctant to speak up in a physical class. In this way, the digital environment is an improvement on face-to-face environments when it comes to identity, allowing for a particular type of connection and interaction, giving students more of a voice and a sense of belonging, while simultaneously allowing them greater control over how they are perceived.

Conclusion

In recent times, with disruptions to all forms of pedagogical rhythms, and the development of new rhythms arising out of necessity, the interruptions to content delivery and technical skill acquisition have been keenly felt and discussed. Indeed, many students may even believe, or voice the opinion, that the acquisition of technical skills is the fundamental purpose of higher education. Such views are, it seems, especially prevalent among those pursuing studies in subjects such as music, where technical ability and prowess are often the most visible application of one’s education and expertise. However, this paper has argued that effective music education is founded not only on technique, but on an understanding and appreciation of the relationship between the musician and their music. Building on the work of Turino, this may be seen as the accumulation and development of self, leading to the curation and communication of an identity, whether authentic or constructed.

Hildegard Froehlich makes the following observation:

Teaching music should always begin with “what makes my students tick.” Although that is hard enough, even harder is perhaps to enable them from there on to explore and discover what is unfamiliar and new to them—something they can sink their teeth into and become increasingly better at doing… I nearly always found myself torn between roles of gatekeeper and gate opener.33

We are in a situation now where, more than ever, there is a need to identify what makes our students tick. At the heart of this is the concept of identity. Weller asserts that educational institutions are “fundamentally influential in fostering social connections, and, therefore, are implicated in shaping identities.”34 Students and educators alike must be aware of the centrality of identity in every interaction. Each encounter, whether with an idea, an experience, or an individual, is an act of identity negotiation, and within the university environment, students are faced with daily opportunities to explore and express their identities. Going forward, we need not only to open the gates, but equip our students with the understanding to discover how to find and open gates for themselves. While the rhythms of daily life and education may have been disrupted, we are able to enable the establishment of new rhythms. The foundation of these new rhythms requires stability, and the varied experiences of the global pandemic have shown us that stability looks different for each individual. The realities of COVID-19 make no distinctions between individuals, yet each views and experiences the situation slightly differently. In a similar way, the fundamental elements of music are recognised and accepted by musicians and students within the same tradition, but the true value comes from enabling our students to explore and create experiences and meaning, using shared tools, but in a way that is specific to their own situation, in other words, their own identity.

Footnotes

1 Barker

2 Lawler

3 Deaux

4 Deaux

5 Cote and Levine

6 Blumer 2

7 Elliot 89

8 Collins

9 Chang and Gomes 39

10 Faye and Sharpe 196

11 Faye and Sharpe 196

12 Reed and Dunn

13 McClellan 280

14 qtd in McClellan 281

15 McClellan 281

16 Scanlon et al. 228

17 Scanlon et al. 230

18 Jensen and Jetten 1

19 Jensen and Jetten 1

20 Jensen and Jetten 6

21 McClellan 289

22 qtd in Weller

23 Scanlon et al. 232

24 Scanlon et al. 233

25 Swann and Bosson 449

26 Turino 112

27 Turino 101

28 Turino 95

29 Scanlon et al. 235

30 Dam

31 Toor

32 Dam

33 qtd in Smith

34 Weller

References

Barker, Chris. The SAGE Dictionary of Cultural Studies. E-Book, SAGE Publications, 2004.

Blumer, Herbert. Symbolic Interactionism. Prentice-Hall, 1969.

Chang, Shanton, and Catherine Gomes. “International Student Identity and the Digital Environment.” Learning across Cultures: Locally and Globally, edited by B Kappler Mikk and I. E. Steglitz, NAFSA and Stylus Publishing, 2017, pp. 39–62.

Collins, Barry. “Zoom Zings Into The Oxford Dictionary Words Of The Year.” Forbes, Nov 23 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/barrycollins/2020/11/23/zoom-zings-into-the-oxford-dictionary-words-of-the-year/?sh=23432faaa465.

Cote, James, and Charles Levine. Identity Formation, Youth, and Development. E-Book, Taylor & Francis, 2015.

Dam, Linda. “Pandemic Pedagogy: Disparity in University Remote Teaching Effectiveness.” Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education during COVID-19: International Perspectives and Experiences, edited by Roy Y. Chan et al., E-Book, Routledge, 2021.

Deaux, Kay. “Models, Meanings and Motivations.” Social Identity Processes, edited by Dora Capozza and Rupert Brown, E-Book, 2000.

Elliot, Richard. Fado and the Place of Longing: Loss, Memory and the City. Ashgate, 2010.

Faye, Cathy, and Donald Sharpe. “Academic Motivation in University: The Role of Basic Psychological Needs and Identity Formation.” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, vol. 40, no. 4, 2008, pp. 189–99.

Jensen, Dorthe H., and Jolanda Jetten. “Bridging and Bonding Interactions in Higher Education: Social Capital and Students’ Academic and Professional Identity Formation.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 6, 2015, pp. 1–11.

Lawler, Steph. Identity. E-Book, Wiley, 2014.

McClellan, Edward. “Undergraduate Music Education Major Identity Formation in the University Music Department.” Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, vol. 13, no. 1, 2014, pp. 279–309.

Reed, Jack, and Catherine Dunn. “Life in 280 Characters: Social Media, Belonging, and Community during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education during COVID-19: International Perspectives and Experiences, edited by Roy Y. Chan et al., E-Book, Routledge, 2021.

Scanlon, Lesley, et al. “‘You Don’t Have like an Identity... You Are Just Lost in a Crowd’: Forming a Student Identity in the First-Year Transition to University.” Journal of Youth Studies, vol. 10, no. 2, 2007, pp. 223–41.

Smith, Gareth Dylan. “Popular Music Education: Identity, Aesthetic Experience, and Eudaimonia.” The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music Education: Perspectives and Practices, edited by Zack Moir et al., E-Book, Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

Swann, W. B., and J. K. Bosson. “Identity Negotiation: A Theory of Self and Social Interaction.” Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, edited by O. P. John et al., The Guilford Press, 2008, pp. 448–71.

Toor, Rachel. “Turns Out You Can Build Community in a Zoom Classroom.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, https://www.chronicle.com/article/turns-out-you-can-build-community-in-a-zoom-classroom. Accessed 8 Oct. 2021.

Turino, Thomas. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago UP, 2008.

Weller, Susie. “Young People’s Social Capital: Complex Identities, Dynamic Networks.” Young People, Social Capital and Ethnic Identity, edited by Tracey Reynolds, E-Book, Routledge, 2011.

Essays

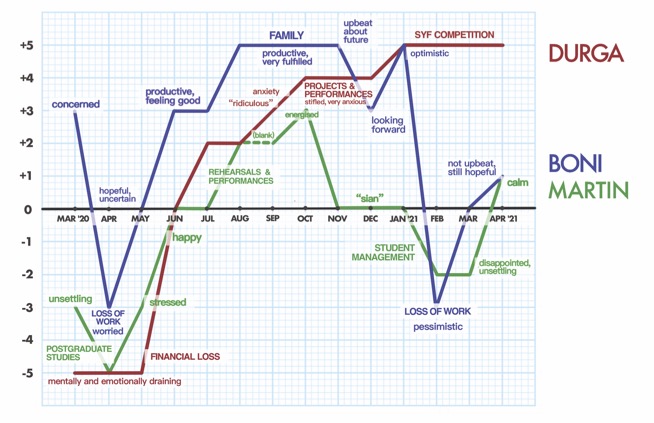

Keeping the Distance - Introduction

Lockdown, circuit breaker, and social distancing are some of the words and notions of disruption that became a lived reality for people around the globe in 2020 and much of 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused us to change regular rhythms and altered movement patterns in everyday life. The symmetry of work, relationships, and routine activities were severely unsettled with few answers to questions of when it will end, or when the new normal might begin. Our bodies were made to spatially distance, which may be more accurately described as physical distancing defined by mathematical measures taking the form of metres or the number of people we were allowed to meet, rather than social distancing which could be overcome through the use of technology. These circumstances subsequently had severe impacts on tertiary dance education in Singapore and globally.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that traditional notions of teaching and learning in tertiary dance education at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) were halted for several months. Dance lessons that would normally take place in a studio setting were either replaced by homework or moved online. As a consequence of these shifts in delivering the learning objectives, educators were unexpectedly forced to learn and improvise with digital media and enact a fundamental shift in the way they communicated and interacted with students. In other words, all of a sudden, tertiary dance education took place via laptops and desktop computer screens which subsequently heavily influenced the accessibility and fluidity of dance learning, creation, and performance.