VOLUME

ISSUE 12

Playground

Playground – a vast, open free space set for socio-cultural, physical-embodied and artistic creative explorations. Often deeply associated with the developmental journey of humans as children, it has historically remained a boundless space of raw discovery, joy and social bonding. From spaces fecund with human potential, playgrounds have transformed, in much of the late twentieth century, into normative, adult spaces – determined and managed by adults as to what people (both as children and adults) should explore, how to consume and perform play. Attendant to this is how to determine the safety and surveil interaction with others.

ISSUE 12

2023

Playground

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Exhibition

Essays

Conversation: Phnom Penh

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Playground

Exhibition

Ideas for Planet(ary) Playgrounds

Conversation: Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh: Art, National Comfort in a Decolonising Southeast Asia

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Cover Image

Milenko Prvački, Hopscotch, 2023, pen and ink, coloured in photoshop.

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy Editor

Weixin Quek Chong

Advisor

Milenko Prvački

Editorial Board

Professor Patrick Flores, University of the Philippines

Dr. Peter Hill, Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne

Professor Janis Jeffries, Goldsmiths, University of London

Dr. Charles Merewether, Art Historian, Independent Researcher, Curator and Scholar

Manager

Sureni Salgadoe

Contributors

Samit Das

FX Harsono

Dr. Peter Hill

Mella Jaarsma

Magdalena Magiera

Dr. Charles Merewether

Sopheap Pich

Professor Claire Roberts

Khvay Samnang

The Editors and Editorial Board thank all reviewers for their thoughtful and helpful comments and feedback to the contributors.

Introduction

Introduction: Playground

The issue of 2023 is Playground.

The intent for choosing playground as a theme was originally to be playful and wispy since the last three volumes were sombre illustrations of the arts’ response to a global health crisis. However, playground as a concept cannot remain playful. It is complex. While seemingly innocuous, play and ground as autonomous descriptors evoke some predictable responses. On the one hand, it could target the evergreen youthfulness of one’s yesteryear. That is our childhood’s central journey at a playground as being deterministic of self-actualisation through play on a ground removed from the embodiment of structures called home or school. However, play conjoined with ground conjure a multi-layered interplay of influences taxed with participatory adult games of war, peace, power and competition.

This volume commissioned artists, writers and art historians to look at the playground concept and investigate its potency as a vast, open and accessible space for sociocultural, physically embodied and artistically creative explorations. The essays reflect on a playground’s normative and performative structures, especially in an increasingly surveilled terrain. The articles do not theorise or romanticise the playground but enlist its conceptual and social philosophies to speak to issues of concern to artists.

More than ever, playgrounds are weighed with contested freedoms of identities and ideologies in the determination of socio-cultural-political space. Whose space, what is contained within a space, who is entitled to be in this space and who controls the area are questions that remain in negotiation. In fact, this has been at the heart of the formation of the 20th century’s primary political offering: the postcolonial nation-state, an endless line of perforations between communities, identities, languages, oceans and ideas—and an increasingly digital sphere of generative AI. The essays, conversation, reflections and exhibition echo a deeply anxious moment in history as we strive for attention in an otherwise noisy set of circumstances.

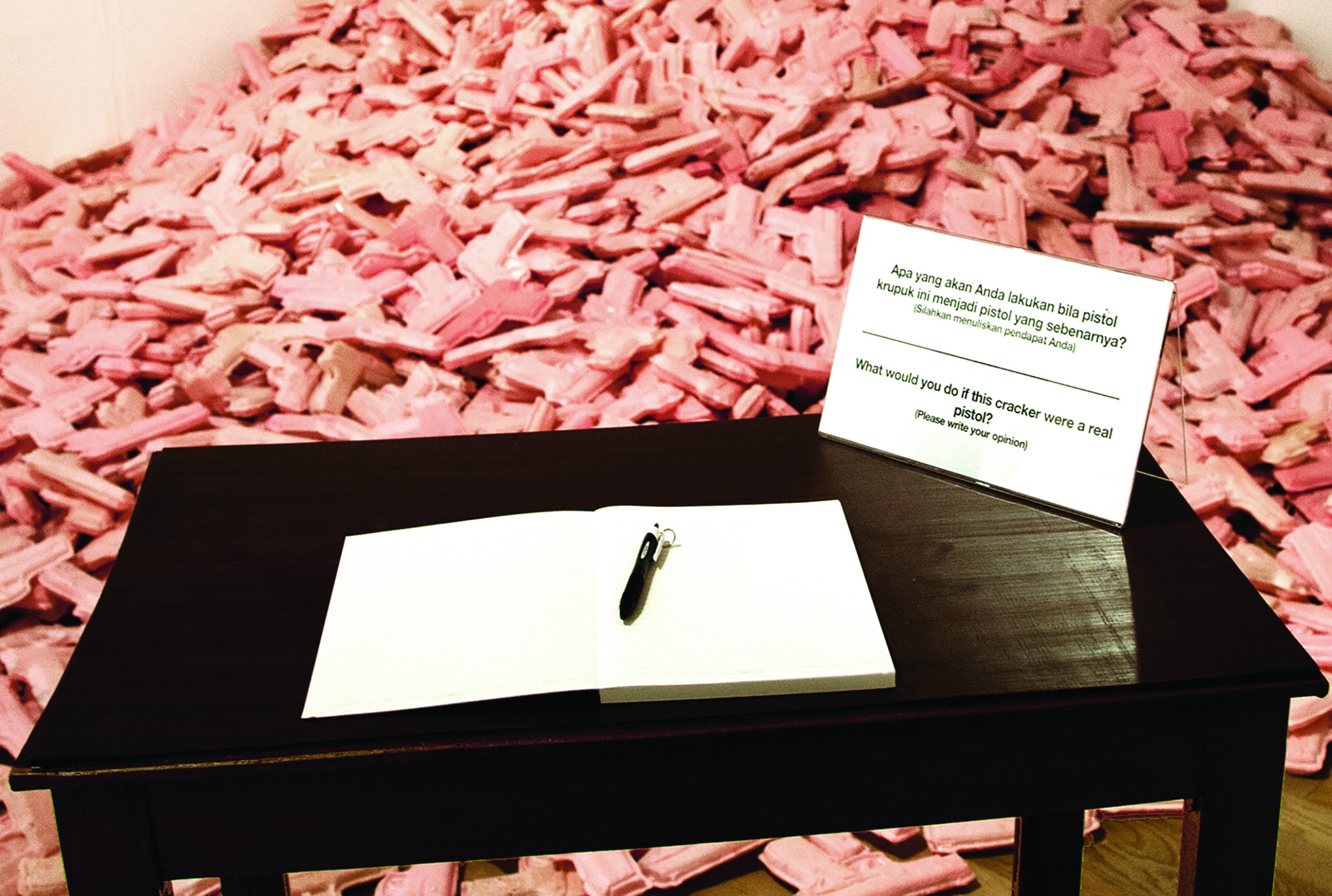

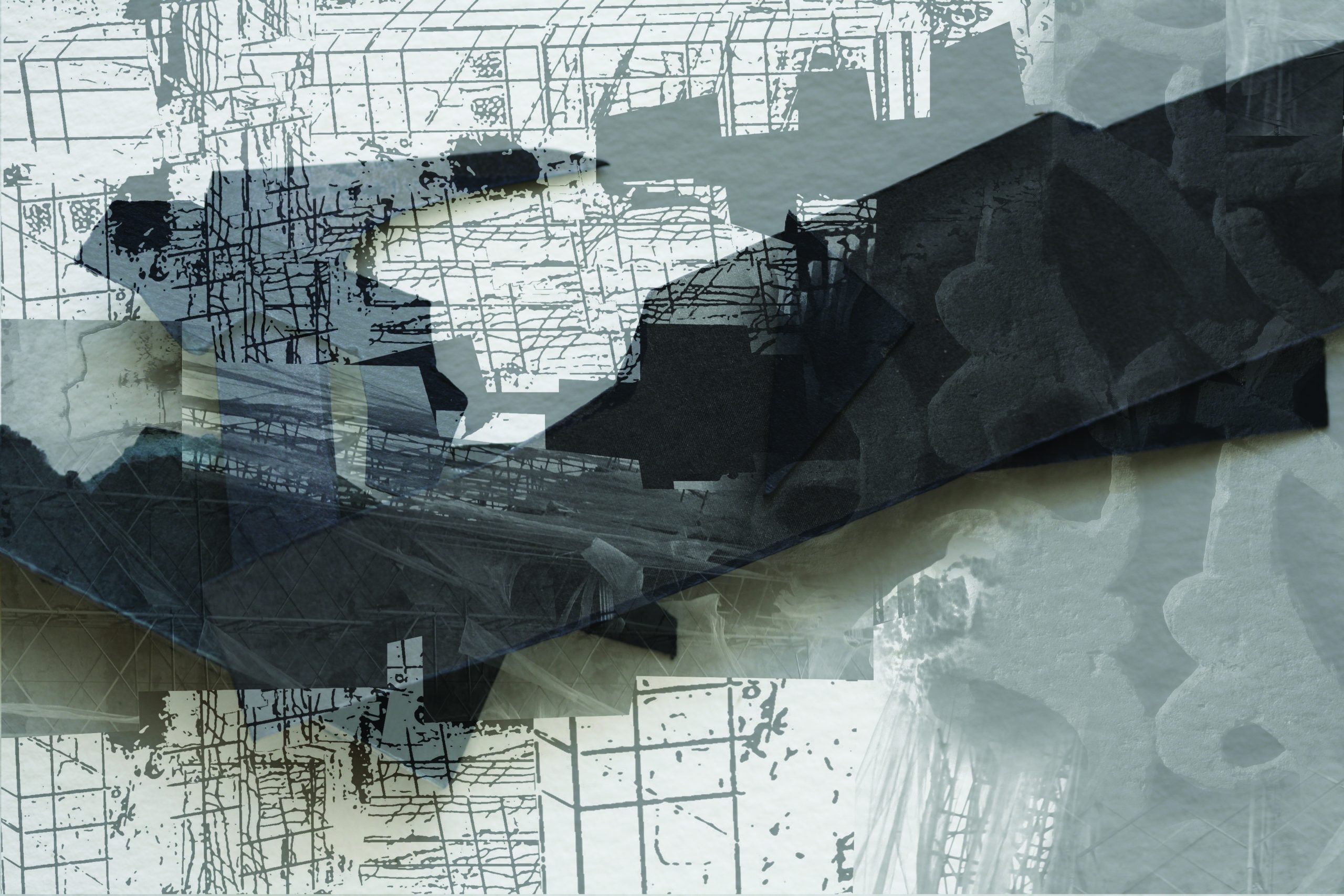

Exhibition

Ideas for Planet(ary) Playgrounds

The right to the city “manifests itself as a superior form of rights: the right to freedom, to individualization in socialization, to habitat and to inhabit”— Lefebvre*

The concept of having the right to places of encounter and exchange, to their life rhythms and time uses, enables the full agency of these moments and places. Within the following pages, I want to explore the idea of Playgrounds shaping multiple aspects of human experience. Playgrounds are gaining even more importance as zones of physical interaction in an increasingly digital world.

The notion of “play” is present in Henri Lefebvre’s concept of the right to the city, as the latter “stipulates the right to meetings and gatherings (…) the need for social life and a centre, the need and the function of play, the symbolic functions of space”. Drawing on this idea, this issue profiles artistic practices and specific works which create accessibility through playful engagement with complex topics and contemporary conflicts. These encounters can influence social, cultural, political, and economic perceptions. Some explore our desires by breaking down the narration of stories within an urban context, like Never Again by Monica Bonvicini, or Rules for the Expression of Architectural Desires by Debbie Ding; others engage with political struggles, like immigration and the experience of minorities reflected in Mr. Cuddle by Trevor Yeung or Moth (that Flies by Day) by Ong Si Hui. The rights of citizens to participate in decision-making processes can be seen in Superkilen by SUPERFLEX or Spiel-Skulptur / Play Sculpture by Regina Maria Möller, as they reflect on shared contemporary experiences.

Each of the works call for new epistemological approaches that look at art as the ever-changing outcome of a production process in which social and physical realities interact with mental ones, enabling a direct conversation with the work as (or through) “play”. Each work engages in a dismantling of their original intention, and therefore their reception becomes unscripted and challenges visitors to rethink their meaning. In some of the works, audiences are invited to claim agency and choose their own interpretations of the work, and the world, through playful engagement and interaction. The works presented here are intended to become constructive ways of un-learning and play, creating a dialogue within civil society and contributing to shaping individuals within a larger community. Changes in the perception of everyday life are what provides the impetus for major changes in society.

Monica Bonvicini

Monica Bonvicini (b. 1965, Italy) emerged as a visual artist and started exhibiting internationally in the mid-1990s. Her multifaceted practice investigates the relationship between architecture, power structures, gender and space. Her research is translated into works that question the meaning of making art, the ambiguity of language, and the limits and possibilities connected to the ideal of freedom. Dry-humoured, direct, and imbued with historical, political and social references, Bonvicini’s art never refrains from establishing a critical connection with the sites where it is exhibited, its materials, and the roles of spectator and creator. Since her first solo exhibition at the California Institute of the Arts in 1991, her approach has formally evolved over the years without betraying its analytical force and inclination to challenge the viewer’s perspective while taking hefty sideswipes at patriarchal, socio-cultural conventions.

Never Again

Monica Bonvicini began creating large-scale architectural installations in the 1990s exploring the built environment and how articulations of power and (sexual) identity define our construction of space. Never Again consists of a collection of swings composed from steel pipes, black leather and chains, suspended from a steel structure. The viewer navigates and physically engages with these subversive structures, all the while altering the politics of traditional exhibition viewing. Incorporating research on psychoanalysis, sexuality, labour, feminism, and architecture, the work of Bonvicini addresses how urban, private, and institutional spaces dictate our behaviour. As a societal and structural critique, Never Again comments on how minimalist art sanitised itself from the body.

Monica Bonvicini, Never Again, 2005.

Galvanised steel pipes, black leather, black leather men’s belts, galvanised chains, clamps. 350 x 1600 x 1100 cm.

Installation view at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2005. Photo: Jens Ziehe. Courtesy the artist and VG-Bildkunst, Bonn.

Chang Wen-Hsuan

Chang Wen-hsuan (b. 1991, Taiwan) questions the narrative structure of institutionalised history with re-readings, re-writings, and suggestions of fictional alternatives in order to expose the power tensions embedded in historical narratives. Through versatile platforms including installations, videos, and lectures, Chang often navigates skewed documentations and first-person accounts to trigger reflections on how the understanding of history affects the purport of the present and thrust of the future. In 2018, she launched the project Writing FACTory. she is the recipient of several awards and prizes and has presented internationally.

Lecture Performance Syllabus

Lecture Performance Syllabus is a trilogy consisting of When Did the Merlion Become Extinct?—The Narrative to Succeed in the 21st Century (2019-2021); The Equipment Show (2021-2022); and The Ventriloquist (2021), which aims at exemplifying the interrelation between narration, performance, and the execution of power. In When Did the Merlion Become Extinct? —The Narrative to Succeed in the 21st Century, the artist delivers a lecture in a way reminiscent of a successology lecturer Victoria Chang, who defines the successology needed in the 21st century as the “National Narrative to Succeed” by breaking down the narratology into simple stories, affective stories, infectious stories, and democratic stories. While the first part of the trilogy examines the verbal language of authoritarian regimes, the second scrutinises the non-verbal communication of the strongman politics. The Equipment Show collects video clips including excerpts of historical figures, politicians, movie characters, and motivational speakers from YouTube, with the stage performer invited to deconstruct those gestures and also make a tutorial video, and “Victoria Chang” analysing the structural relationships between texts and the images. The last one, The Ventriloquist, deconstructs the narratology and performativity of the strongman by unveiling the technique of suture with the disclosure of dubbing. Combining video, installation, documents, and lecture performance, the trilogy probes into the governmentality of strongman, the designation of audienceship, and the unaccomplishment of democracy.

Chang Wen-Hsuan, When Did the Merlion Become Extinct?—The Narrative to Succeed in the 21st Century. 2019-2020.

Photo: Bat Planet Photography. Courtesy Taiwan Contemporary Culture Lab (C-LAB).

Chang Wen-Hsuan, The Ventriloquist. 2021.

Installation view, Lecture Performance Syllabus: Chang Wen-Hsuan solo Exhibition, Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts. 2021.

Courtesy the artist.

Chang Wen-Hsuan, The Equipment Show. 2022.

Installation view, Making Worlds: An Imagineering Project, Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, 2022.

Photo: ANPIS FOTO, Anipis Wang. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei.

Kray Chen

Kray Chen (b. 1987, Singapore) is a visual artist dealing with film, performance and installations. Kray is fascinated with social rituals where he often finds the peculiar or absurd to look at the gaps between what we imagine and what we find in real-life. He has presented internationally and is the recipient of the 2017 National Arts Council’s Young Artist Award.

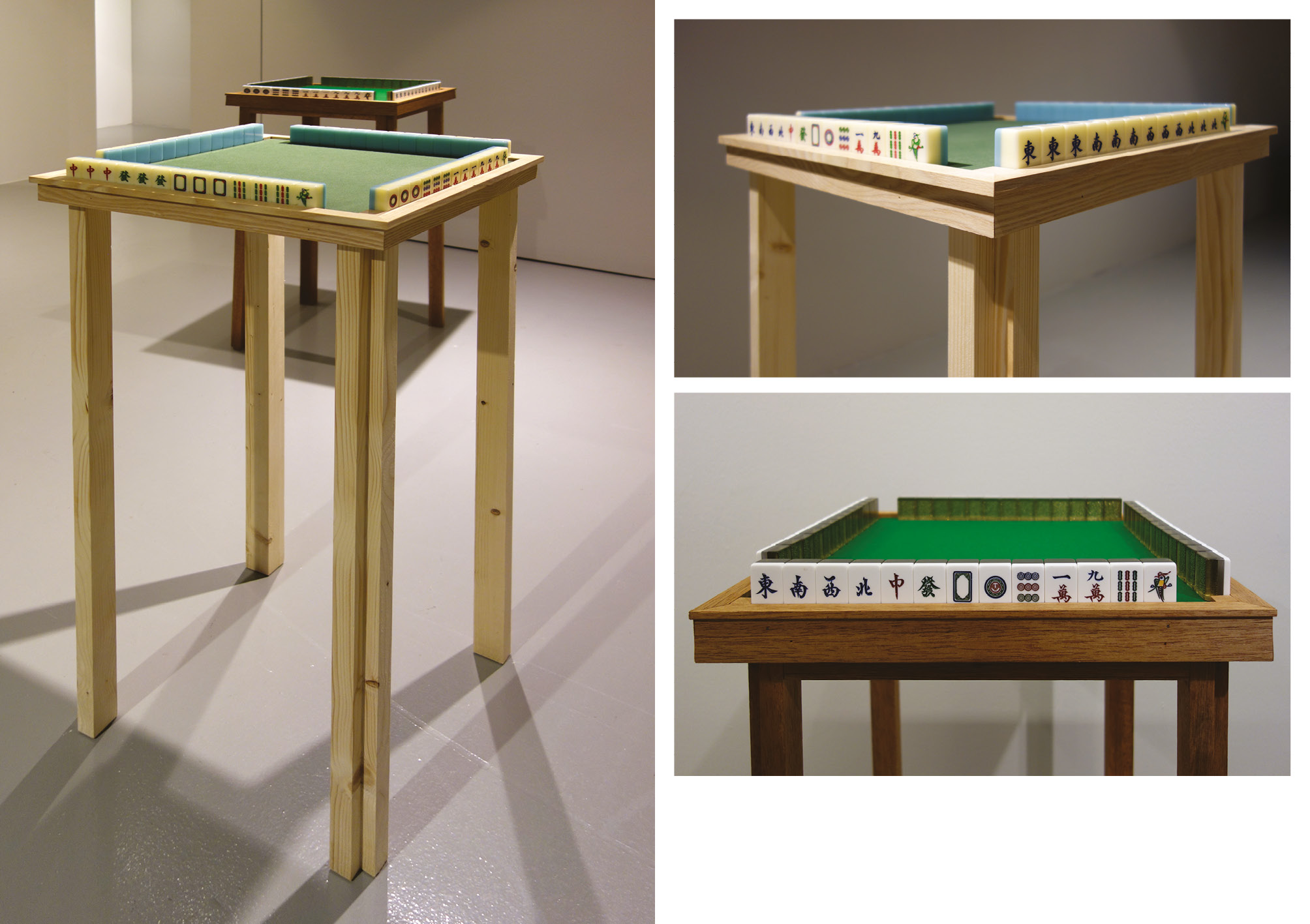

Waiting for the Bird #1 and #2

In the Waiting for the Bird series, the sculptures condense the dimensions of Mahjong, figuratively and metaphorically, into a tight-fitting diorama that are inspired by the dramatic depictions of legendary Mahjong gameplays in Hong Kong films. Chen recreates the scenarios where each player, although gifted with legendary winning hands, are stuck in an impasse where everyone waits for the last Bird tile.

Kray Chen, Waiting for the Bird #1 (lightwood), 2018 and Waiting for the Bird #2 (darkwood), 2019.

Collected Mahjong tiles, wood, fabric. Installation view IN RANDOM, 23 January – 3 March 2019, Fost Gallery, Singapore.

Courtesy the artist and Fost Gallery.

Heman Chong

Heman Chong (b. 1977, Malaysia, raised in Singapore) is an artist whose work is located at the intersection between image, performance, situations and writing. His practice can be read as an imagining, interrogation and sometimes intervention into infrastructure as an everyday medium of politics. His work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at many international Institutions. Chong is the co-director and founder (with Renée Staal) of The Library of Unread Books, a library made up of donated books previously unread by their owners.

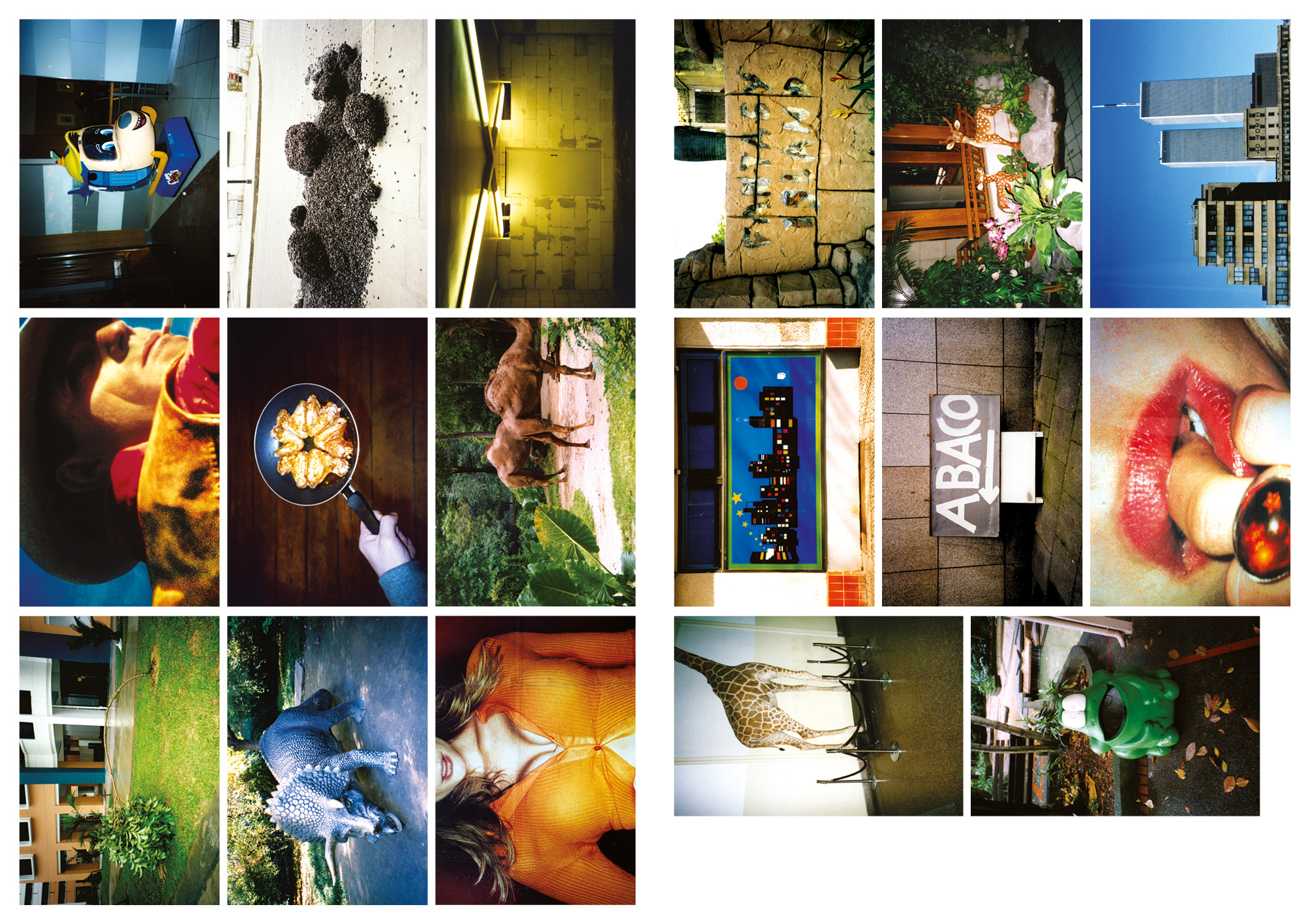

God Bless Diana

A series of images collected in a rigorous manner over five years and totalling around 6,000, which have been edited down to a set of 550. Displayed as a postcard shop, the work reflects on the process of collecting. Of interest to Chong is the process of accumulation that very immediately slips into the dissemination of an archive, and how this archive becomes open to its availability. The idea that people curate their own viewing experiences, rather than having somebody else define these, is an important aspect to the artist. When buying the postcards, people need to go through the selection process and create their own ways of seeing. This archive is an early work by Heman Chong when he was at the very beginning of his artistic practice. It encapsulates themes that later resurface in his works, like collectivity, monumentalisation, objects, displaced systems, performativity, time, art history, and death.

This project was initially commissioned for the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands.

Heman Chong, God Bless Diana, 2000-2004.

17 / 550 postcards. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Amanda Wilkinson Gallery.

Debbie Ding

Debbie Ding (b.1984, Singapore) is a visual artist and technologist whose interests range from historical research and urban geography to visions of the future. She reworks and re-appropriates formal, qualitative approaches to collecting, labelling, organising, and interpreting assemblages of information – using this to open up possibilities for alternative constructions of knowledge. Using interactive computer simulations, rapid prototyping, and other visual technologies, she creates works about subjects such as map traps, lost islands (Pulau Saigon), World War II histories, soil, bomb shelters, and public housing void decks.

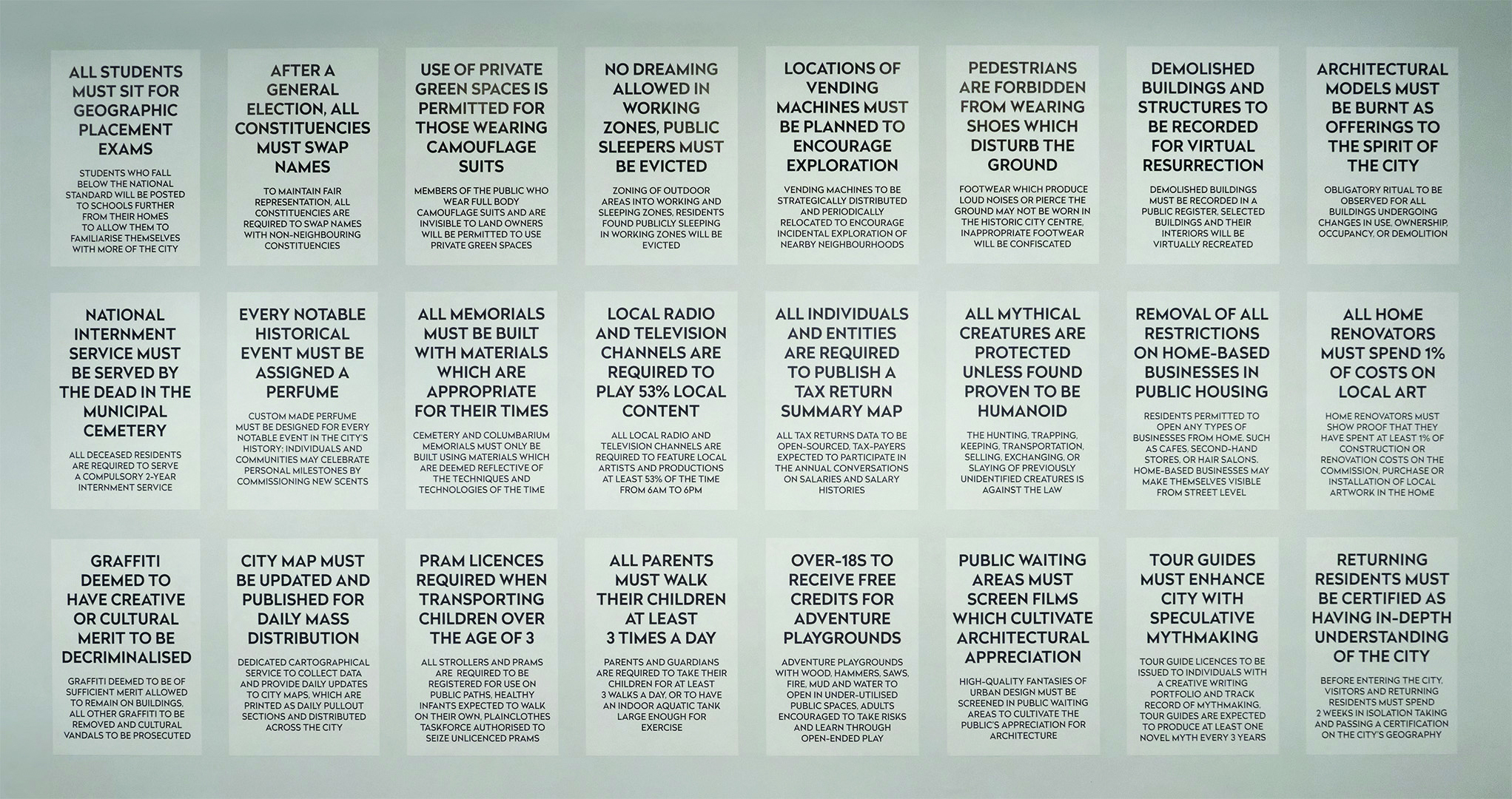

Rules for the Expression of Architectural Desires

The design of our built environment begins with ideas, often articulated in a manner that may be conceptual, abstract, or even imprecise. Even though the city is built with concrete and glass, when we explore its textures we find that its core is made up of ideas, desires and emotions. In order for us to imagine new cities and solutions, we need to re-write the rules.

Rules for the Expression of Architectural Desires is made up of 24 speculative schemes, devices and instruments for the urban and social re-design of a city. Each of these rules is written with the intention of promoting the expression of architectural desires, although it is unclear whether they will change the city for better or worse. You decide.

Debbie Ding, Rules for the Expression of Architectural Desires, 2014-2021.

24 UV printed posters on newsprint paper. Installation view Wikicliki: Collecting Habits on an Earth Filled with Smartphones,

22 April–11 July 2021, Singapore Art Museum. Photo: the artist.

Anne Duk Hee Jordan

Anne Duk Hee Jordan (b. 1978, Korea) Korean-German artist, whose background shaped her interests in art, science, and philosophy. Her work often speaks of issues of migration, identity, and social spaces, using natural or biological processes as metaphors. Her installations are meticulously researched and she often uses humour to get her point across. She uses both living and dead materials, at times constructing machines that can mirror organisms to create a dialogue between art and science, her identity, and social systems.

Making Kin

How do we want to live in the future? In a combination of various media such as living plants, installation, drawings, and robotics, Anne Duk Hee Jordan, explores concepts of interspecies community and real and fictional landscapes. “Making Kin” is a maxim coined by the philosopher of science and pioneer cyborg feminist Donna Haraway who calls for an interspecies symbiosis. To ensure a liveable future for the following generations, we, as mortal “critters”, need to link up with multiple configurations of places, times, matters and meanings so that new life can be “composted” from the planet-destroying Homo sapiens. Jordan scrutinises established terms like nature, culture, and technology, including their definitional boundaries. The artist is interested in the hybrid network between species and their environment. In a humorous and playful manner, she draws up an experimental and future-oriented scenario that challenges our customary perspectives on life and, likewise, makes a new model of community both imaginable and apprehensible. The work Water Crab (2017– ongoing) is conceived to function as a marine robotic. As her Artificial Stupidity series is about allowing failure and reclaiming the domain of robotics in terms of non-intelligence, this Water Crab is not able to clean up all the human waste in the oceans, but is rather a prototype of this idea and advocation that design or art is not only there to make the world a better place. Does a non-functional artificial bot also have the right to float in our waters?

This work was conceived for the exhibition “Making Kin” at the Kunsthaus Hamburg, Germany, curated by Anna Nowak.

Anne Duk Hee Jordan, Making Kin, 2020

Site-specific artificial pond with artificial crab and 2 channel video, along with critters, sea animal sculptures and

drawing. Installation view Making Kin. 3 July – 6 September 2020, Kunsthaus Hamburg. Courtesy the artist.

Valentina Karga

Valentina Karga (b. 1986, Greece) is currently working on challenging the notion of ‘self’ by proposing non-anthropocentric future narratives. A large part of her projects encourage engagement and participation, facilitate practices of commoning and are concerned with sustainability. She works across different media, often inviting a public or a community to literally complete the work. Sometimes, through dialogue and building prototypes in a DIY manner, they end up imagining alternatives for infrastructures and institutions that structure our reality. This is what she calls ‘Art as Simulation’. She is a founding member of Collective Disaster, an interdisciplinary group that works in the interstices of architecture and the social realm.

Well Beings

In the exhibition Well Beings at the MK&G (Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg), artist, architect and designer Valentina Karga deals with the fears triggered by ecological crises. Based on her own experience with such anxieties, she has developed an interactive parkour that invites visitors to try out for themselves various exhibits inspired by popular self-care objects. These include hug-pillows and weighted blankets as well as oversized plush toys that are blown-up versions of small figurines from the museum’s Antiquities Collection.

Valentina Karga, Well Beings, 2023.

Upholstery, natural and recycled materials, natural dyes, HD video, sound. Installation view, Valentina Karga: Well Beings, 24

March–3 September 2023, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg. Courtesy the artist.

Lai Yu Tong

Lai Yu Tong (b. 1996, Singapore) is a visual artist whose works span across image-making, painting, drawing and installation. He makes works about the things he sees, things he eats, things he buys, things he throws away, and more, examining habits of consumption in the modern world.

Rearrange The World

Rearrange The World is a series of 30 paper-cut collages that depicts a game being played between two hands, one of which bears a bandage around its thumb. Three objects—a cup, a can, and a bottle—are moved about on a table, tumbling, balancing, rolling and overturning around one another, forming new configurations at each turn. The words ascribed to the objects are a combination from common vocabulary taught to children and words that the artist hopes to teach to children. The work reflects on the possibility of changing the world by rearranging it.

A version of this work will be produced into a children’s book, published by Thumb Books, a small press founded by the artist in 2022 that makes children’s books for both children and adults.

Lai Yu Tong, Rearrange the World, 2023.

15 / 30 paper-cut collages.

Graphite, copier-paper, recycled paper. Courtesy the artist.

Regina Maria Möller

Regina Maria Möller (b.1962, Germany) is the founder of the magazine regina and creator of the label embodiment. Her artistic practice is conceptual and involves a wide range of media formats; interweaving complex stories, which deal with, for example, the question of identities, the physical body’s presence in digital times, and the environment at large. When the Corona pandemic broke out in March 2020 Möller worked together with historians from science, technology, medicine and the environment on the research project The Mask – Arrayed, hosted by the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG). The projects and works of Regina Maria Möller have been exhibited nationally and internationally.

Spiel-Skulptur / Play Sculpture

Since her early career, Möller’s interest lays in producing artworks that could be used or worn to challenge the social capacities of the aloof. With Play Sculpture, an ‘Art in Public Space’ for a kindergarden in Großmugl, Germany, she created a sculpture that doubles as a playground. The climbing structure is based on children’s drawings, and the rectangular box on top of the climbing frame represents a moving cardboard box. Children can access the box from entrances on two sides, one round and the other square. Both openings are framed by a graphic drawing of an open box, creating a ‘trompe-l’oeil’ effect from a distance. The interior of the box is covered with green chalkboard paint so that children can constantly redesign their four walls without being observed by their parents or kindergarten teachers. On the closed sides of the moving box, the words ‘children’s room’ or ‘living room’ can be read in six different languages, referring to Austria’s neighbouring countries and vast international communities.

Großmugl’s Cat

Years later at the same kindergarden in Großmugl, Möller developed a second public art project doubling as playground: Großmugl’s Cat. The name of the town is derived from a large Bronze Age burial mound nearby. Möller invokes this historical site by creating a small hill alongside a large cat sculpture. An opening in the mound serves as a tunnel through which children can escape the lurking cat, which also functions as a climbing wall. The work embodies an ethic of work and play, consistent with the motto of Charles and Ray Eames, “We must take the game seriously.”

Regina Maria Möller, Großmugl’s Cat, 2011.

Installation view Kindergarten Großmugl, Photo: Regina Maria Möller. Courtesy the artist and Niederösterreichische

Landesausstellung, Abt Kunst und Kultur / Kunst im öffentlichen Raum / Marktgemeinde Großmugl.

Drawing by Thomas Möller, Großmugl’s Cat and Play Sculpture, 2011.

Courtesy the artist and VG Bild-Kunst Bonn.

Regina Maria Möller, Spiel-Skulptur / Play Sculpture, 2001,

Installation view Kindergarten Großmugl. Photo: Werner Kaligofsky. Courtesy the

artist and Niederösterreichische Landesausstellung, Abt Kunst und Kultur / Kunst

im öffentlichen Raum / Marktgemeinde Großmugl

Regina Maria Möller, mousehole / Großmugl’s Cat, 2011.

Detail. Courtesy the artist and VG Bild-Kunst Bonn.

Ong Si Hui

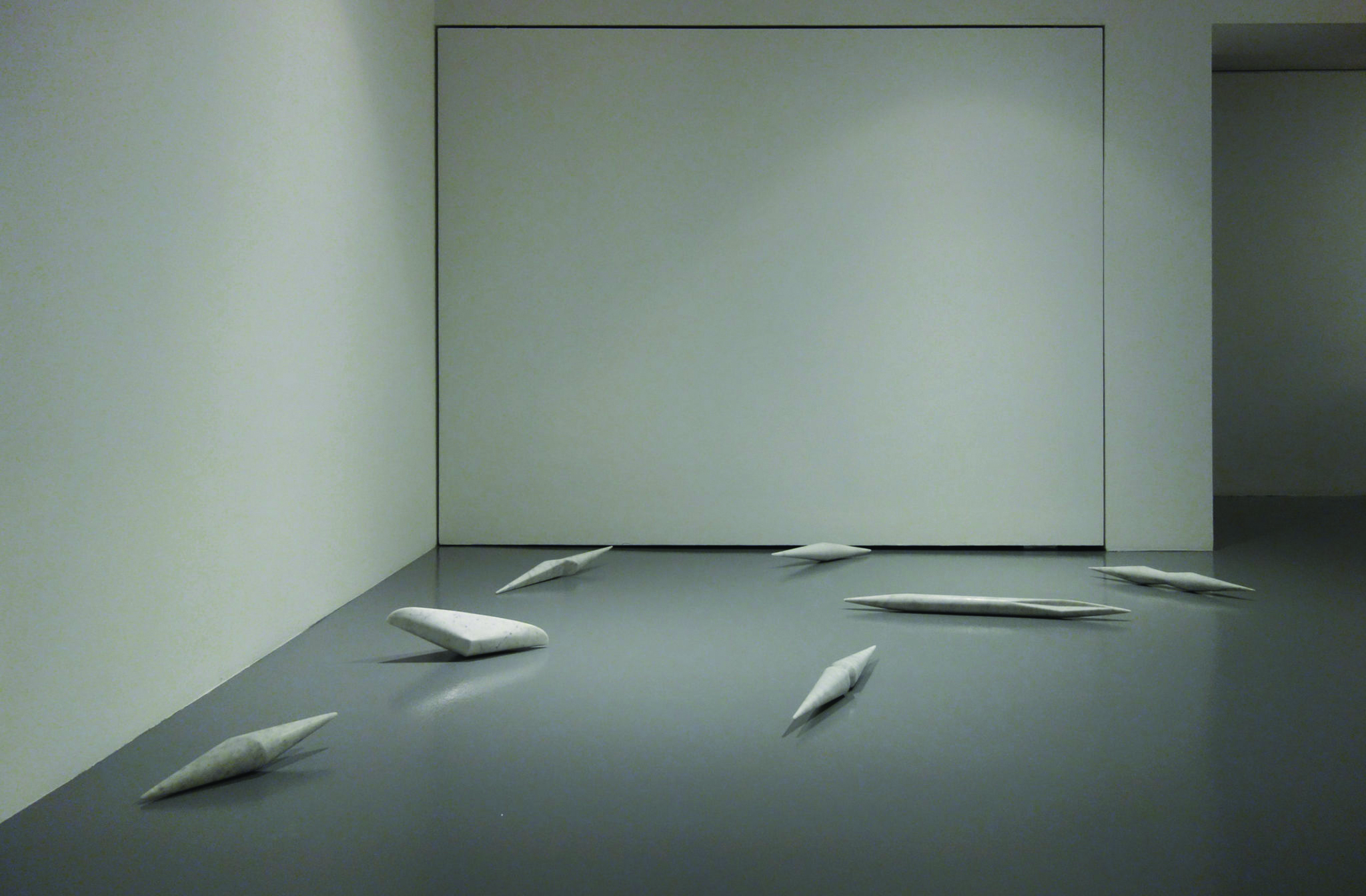

Ong Si Hui (b. 1993, Singapore) is a visual artist based in Singapore. She is a trained sculptor from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts and LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore. Working extensively in stone, she explores the spirit of the medium through slow and meticulous hand carving processes. She addresses materiality, human conditions, fragility, anxiety, and reflects upon the behaviour of a work story. Her geometric forms and text-oriented works are often manifestations of her stream of consciousness.

Moth (that flies by day)

In late 2017, the area where the artist lived was overpopulated with moths; Ong became intrigued by both their boundless energy and complete stillness, that at times happened all at once. The daily scene also reminded the artist of Virginia Woolf’s essay The Death of the Moth, where she described with great dignity a moth’s death.

Thinking about the death of moths, and how their bodies are sometimes fastened down as specimens, stripped of life, Ong wanted to embody their spirit in stone, a medium that instead bears the history of time. This series began as an exploration of energy that lies within dormant forms.

Each form takes after different phases of the moth’s life and is illustrated in its physical qualities. Motions suspended in delicate fashion, with tilted axis, wander forward and backward through a meandering path. Each piece from the series represents the motions or spirit of the moth in different ways, and altogether, it reflects upon the complexity of the short life of a moth.

Through the narrative of the moth, a series of 7 pieces1, relate to the artist’s personal anxiety. Ong experiments with the delicacy of the forms, the brittleness of the marble, and their vulnerability to external movements, all the while containing tremendous amounts of nervous energy within.

1 artwork information of individual pieces: https://www.ongsihui.com/moththatfliesbyday

Ong Si Hui, Moth (that flies by day), 2018.

Marble, series of 7. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Ong Si Hui, Moth (that flies by day). 2018.

Marble. Dimensions variable. Installation view, The Lie of the Land, 07 August–17 October 2021, Fost Gallery.

Courtesy the artist and FOST Gallery.

Marjetica Potrč

Marjetica Potrč (b.1953, Slovenia) is an artist and architect based in Ljubljana. From 2011 to 2018, she was a professor of social practice at the University of Fine Arts/HFBK in Hamburg, where she taught Design for the Living World, a class on participatory practices. She has also been a visiting professor at a number of other institutions, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2005) and the IUAV Faculty of Arts and Design in Venice (2008, 2010). Potrč has received numerous awards, grants, fellowships, and residencies. Her work has been exhibited extensively throughout Europe and the Americas.

Notes on Participatory Design, no. 7, 2014

Art depends on culture and is a tool to change culture itself. When art is a relational object, it mediates our relationship to the world and the artist becomes a mediator.

Marjetica Potrč, Notes on Participatory Design, no. 7, 2014.

Ink on paper. 21 x 29.7 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin/Stockholm/Mexico City.

SUPERFLEX

SUPERFLEX was founded in 1993 by Jakob Fenger, Bjørnstjerne Christiansen, and Rasmus Rosengren Nielsen. Conceived as an expanded collective, SUPERFLEX has consistently worked with a wide variety of collaborators, from gardeners to engineers to audience members. Engaging with alternative models for the creation of social and economic organisation, works have taken the form of energy systems, beverages, sculptures, copies, hypnosis sessions, infrastructure, paintings, plant nurseries, contracts, and public spaces. Working in and outside the physical location of the exhibition space, SUPERFLEX has been engaged in major public space projects since their award-winning project Superkilen opened in 2011. These projects often involve participation and the input of local communities, specialists, and children. Taking the idea of collaboration even further, recent works have involved soliciting the participation of other species. SUPERFLEX has been developing a new kind of urbanism that includes the perspectives of plants and animals, aiming to move society towards interspecies living. For SUPERFLEX, the best idea might come from a fish.

Superkilen

Interview with SUPERFLEX about the work:

Uploaded on https://youtu.be/rlCo4Mg3Rdk

Superkilen is a public space in Copenhagen divided into three main areas: The Red Square, The Black Square and The Green Park. The Red Square represents modern urban life with a café, music and sports, while The Black Square is a classic square with fountains and benches and The Green Park is a park for picnics, sports and walking dogs.

The people living in the immediate vicinity of the park represent more than 50 different nationalities. Instead of including the city objects usually designated for parks and public spaces, SUPERFLEX asked people from the area to nominate objects such as benches, bins, trees, playgrounds, manhole covers and signage from other countries. These objects were chosen either from the country of the relevant inhabitant’s national origin, or from somewhere else encountered through traveling. The objects were either produced in a one to one scale copy or bought and transported to the site.

Furthermore, as part of a process that SUPERFLEX calls ‘extreme participation’, five groups travelled with SUPERFLEX to Palestine, Spain, Thailand, Texas and Jamaica in order to acquire five objects of their choice. These have since been installed in the park. In total, the park now contains more than 100 different objects from more than 50 different countries.

Superkilen was designed in collaboration with BIG and Topotek1. Commissioned by the City of Copenhagen and Realdania, Denmark.

Superkilen, 2012. Red Square. Photo: Iwan Baan.

Superkilen, 2012. Red Square.

Photo: Torben Eskerod.

Superkilen, 2012. Red Square.

Photo: Torben Eskerod.

Superkilen, 2012. Red Square, Thai boxing.

Photo: Iwan Baan.

Superkilen, 2012. Red Square.

Photo: SUPERFLEX.

Superkilen, 2012. Red Square, Bench from Salvador, Brazil.

Photo: SUPERFLEX.

Superkilen, 2012. Black Square.

Photo: Iwan Baan.

Superkilen, 2012. Black Square, Octopus.

Photo: Torben Eskerod.

Superkilen, 2012. Green Park.

Photo: Iwan Baan.

Superkilen, 2012. Green Park.

Photo: Jens Lindhe.

All images Superkilen, 2012. Urban park in Copenhagen. Commissioned by City of Copenhagen and RealDania.

Developed in close collaboration with Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and Topotek1. Courtesy SUPERFLEX.

Berny Tan

Berny Tan (b.1990, Singapore) is an artist, curator, and writer working in Singapore. Her interdisciplinary practice explores the tensions that arise when she applies systems to – and unearths systems in – her subjective experiences. Tan’s strategies also reflect a fundamental interest in language as it is read, written, and spoken by her. As an independent curator, she has developed approaches built on principles of empathy, sensitivity, and collaboration.In 2022, she was awarded the IMPART Art Prize in the curator category.

Page Break

Page Break was a three-month Curatorial and Research Residency at the Singapore Art Museum, presented as part of the Singapore Biennale 2022, named Natasha. As a project, it looked at how everyday objects and scenes are explored through the medium of the art book, particularly within the context of Singapore.

While residencies tend to be insular frameworks for research, Page Break instead allowed the public access to an open studio that hosted Tan’s personal workspace, an exhibition space, an art book library, and occasional programmes. The exhibition evolved over four ‘drafts’, incrementally incorporating book projects by Atelier HOKO, Catherine Hu, Chua Chye Teck and Liu Liling, Genevieve Leong, Lai Yu Tong, and Marvin Tang. The residency thus functioned as a site for collaborations that built on Tan’s existing connections within the visual art community in Singapore, bringing together artists and designers who make art books that examine the otherwise ordinary.

Extending the material exploration of the print medium, waste from print production was repurposed to create partitions and modular furniture which served as either seating or display surfaces. These structures were designed by art director Pixie Tan with support from Sean Gwee of fabrication collective Made Agency. At the conclusion of Page Break, the materials were returned to the recycling process, minimising the waste generated by the project.

Berny Tan, Page Break, 2022-23.

Curatorial and research residency at SAM Residencies. Installation view at Singapore Biennale 2022 Natasha, Singapore Art

Museum at Tanjong Pagar Distripark. Photo: Marvin Tang. Courtesy the artist.

Sung Tieu

Sung Tieu (b. 1987, Vietnam) lives and works in Berlin, Germany and London, UK. Tieu’s work takes place at the intersection of her personal experiences, global history, and the cultural incursions of European art traditions. Her immersive installations result from her research of the dynamics of hegemonic globalised capitalism, working through and with spatial dislocation while paying heed to the cultural testimony of the Vietnamese diaspora communities in Germany. Through the personal lens of post-colonial identity and cultural membership, she upsets the status of objective narrative and of proof when science works at the service of sociopolitical agendas. While addressing social and cultural class divides in both contemporaneity and recent history, Tieu’s work foregrounds the ways evidence is manipulated in imperialist violence, both of physical and psychological nature.

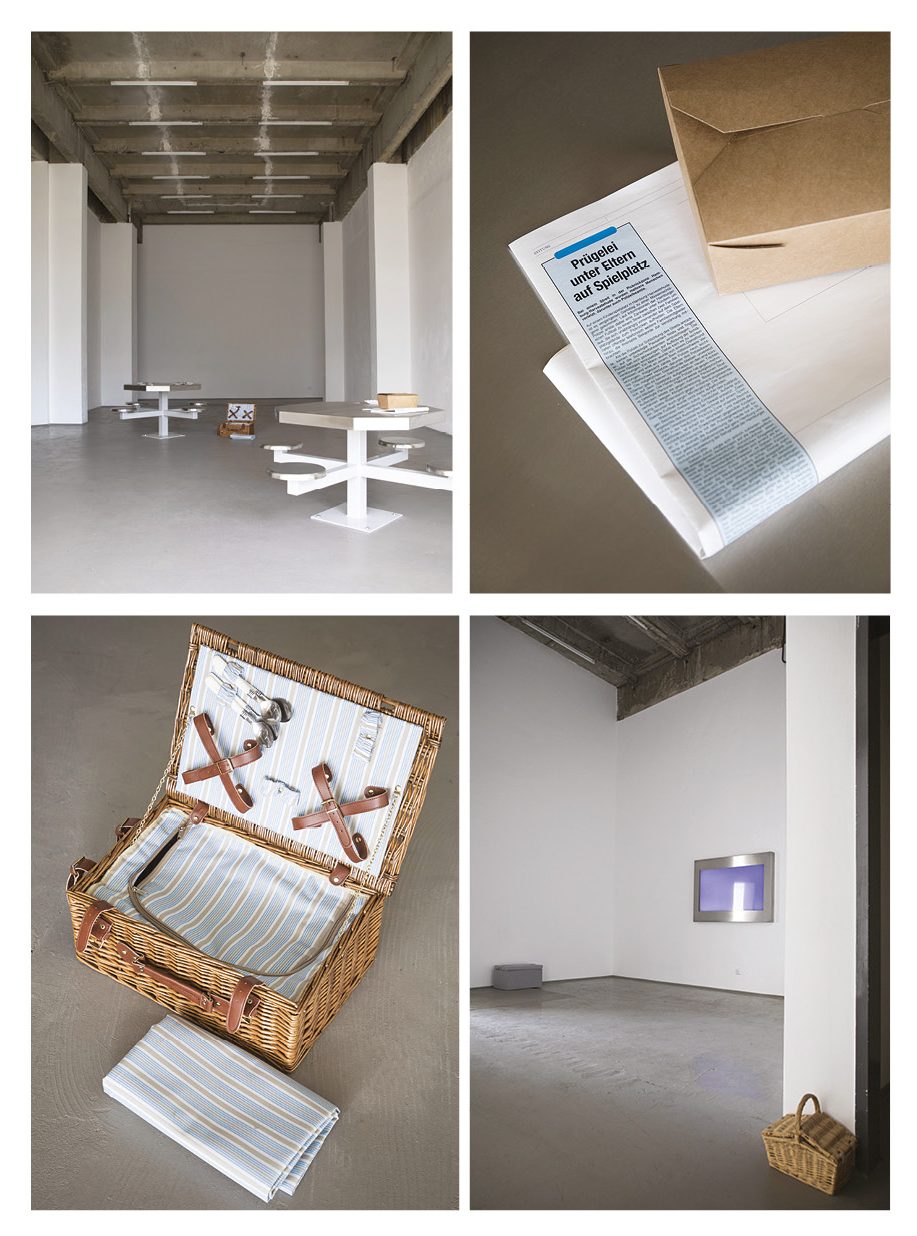

Loveless

Inside the 18th century decor of the gallery, two dining table units designed for custodial environments have been installed. Across their stainless-steel surfaces empty food containers have been left, suggesting they have been recently used. Ambient sound hovers in the room. Composed of field recordings and audio libraries, the noise of kitchen alarms, gates slamming and neon lights flickering have been built in to a single dissonant rhythm that eventually transitions into a melody. Images move across a stainless-steel encased TV screen. The images, like the field recordings, are observational. Through sound and a newspaper clipping specific spatial locations are invoked while the melodies leave an undercurrent of a personal memory. This is contrasted by the sculptural elements that adjure a blank expression of global universalism for the audience to engage with.

Parkstück

Parkstück is the third in a trilogy of exhibitions each comprised of two artworks: Loveless and Formative Years on Dearth (both 2019). Formative Years on Dearth saw Tieu collect, stage and reinterpret a selection of materials from an extensive research of the John Latham Archive. Tieu creates a visual essay by interweaving histories of John Lathams personal life with her own memories. This intuitive personal account used Latham’s voice to entangle the private and the personal with global social and financial narratives.

Sung Tieu, Loveless, 2019.

Installation view, Loveless, Piper Keys, London, UK, 26 January–24 February 2019

Courtesy the artist; Piper Keys, London; and Emalin, London. Photo: Mark Blower

Sung Tieu, Loveless, 2019.

Installation view, Parkstück, Fragile, Berlin, Germany, 01–28 June 2019.

Courtesy the artist, Fragile, Berlin, and Emalin, London.

Trevor Yeung

Trevor Yeung (b. 1988, China) uses botanic ecology, horticulture, aquarium systems and installations as metaphors that reference the emancipation of everyday aspirations towards human relationships. Yeung draws inspiration from intimate and personal experiences, culminating in works that range from image-based works to large-scale installations. Obsessed with structures, he creates different scales of systems which allow him to exert control upon living beings, including plants, animals, as well as spectators.

Mr. Cuddles Under the Eave

Mr. Cuddles Under the Eave is a large-scale installation composed of 13 uprooted pachira aquatica (also widely known as money trees) suspended from the ceiling on an eight– by eight–metre metallic grid. Each tree is leashed onto the hanging structure with ratchet straps tied through the crevices of the tree’s braided branches. The trees are dangled without order, some hanging diagonally and hori-zontally, whilst others are suspended vertically.

The trees are imprisoned to the ruthless harness of ratchet straps, being subjected to a condition of immobility. Standing beneath the installation, one cannot help but feel an imminent menace, weary that the trees may collapse at any moment. The state of restraints embodied in Mr. Cuddles mirrors the lockdowns of the last few years. The interdependency between people during isolation is not unlike the branches of the money trees, which are actually multiple plants woven together during growth; they are fated and without escape. These leashed trees personify a collective anxiety, power-lessness and fragility.

Trevor Yeung, Mr. Cuddles Under the Eave, 2021.

Pachira trees, straps. Dimensions variable. Installation view Art Basel Hong Kong 2023. Photo: South Ho.

Courtesy the artist and Blindspot Gallery.

Footnotes

* Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. (p.195)

Essays

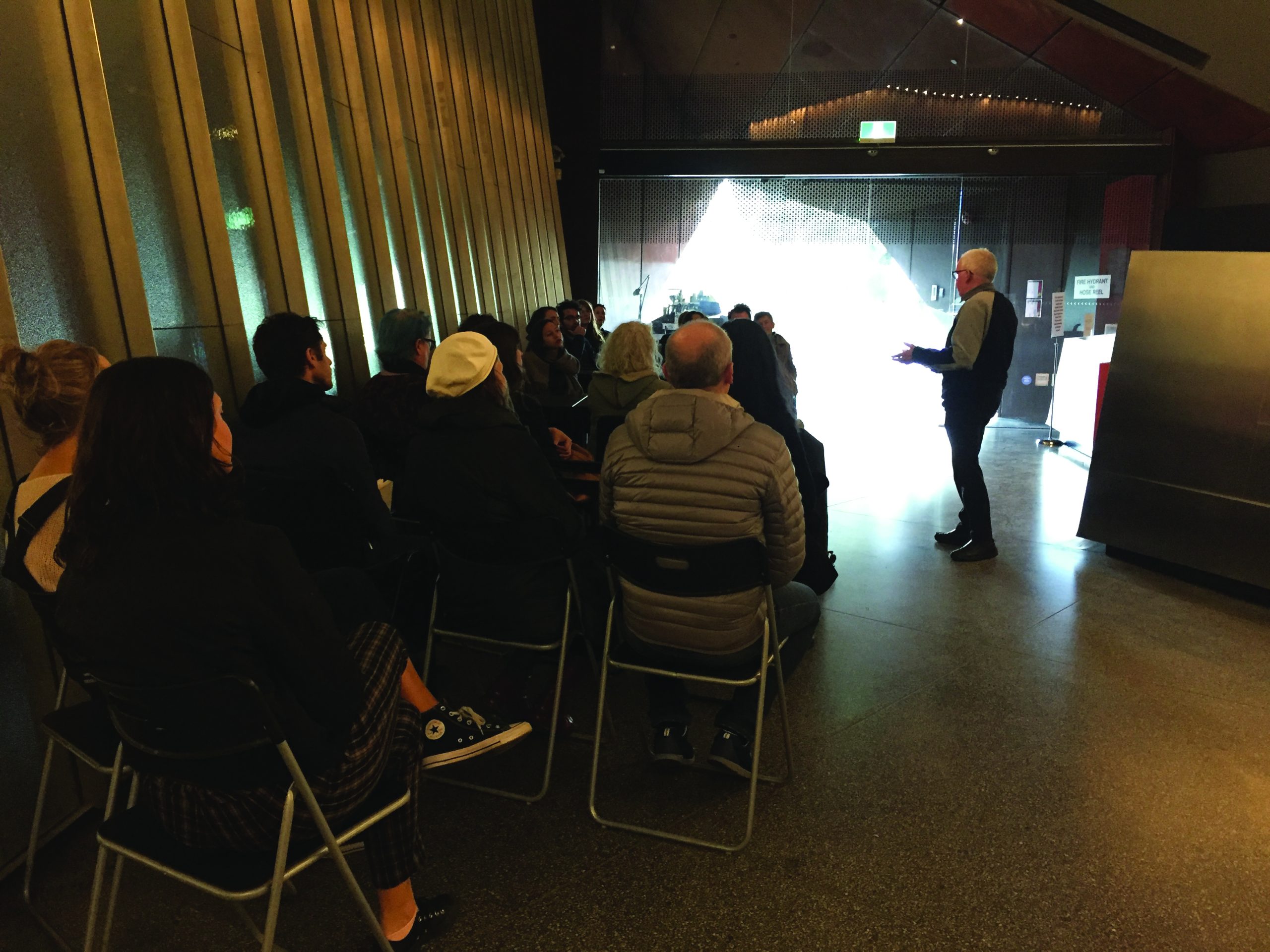

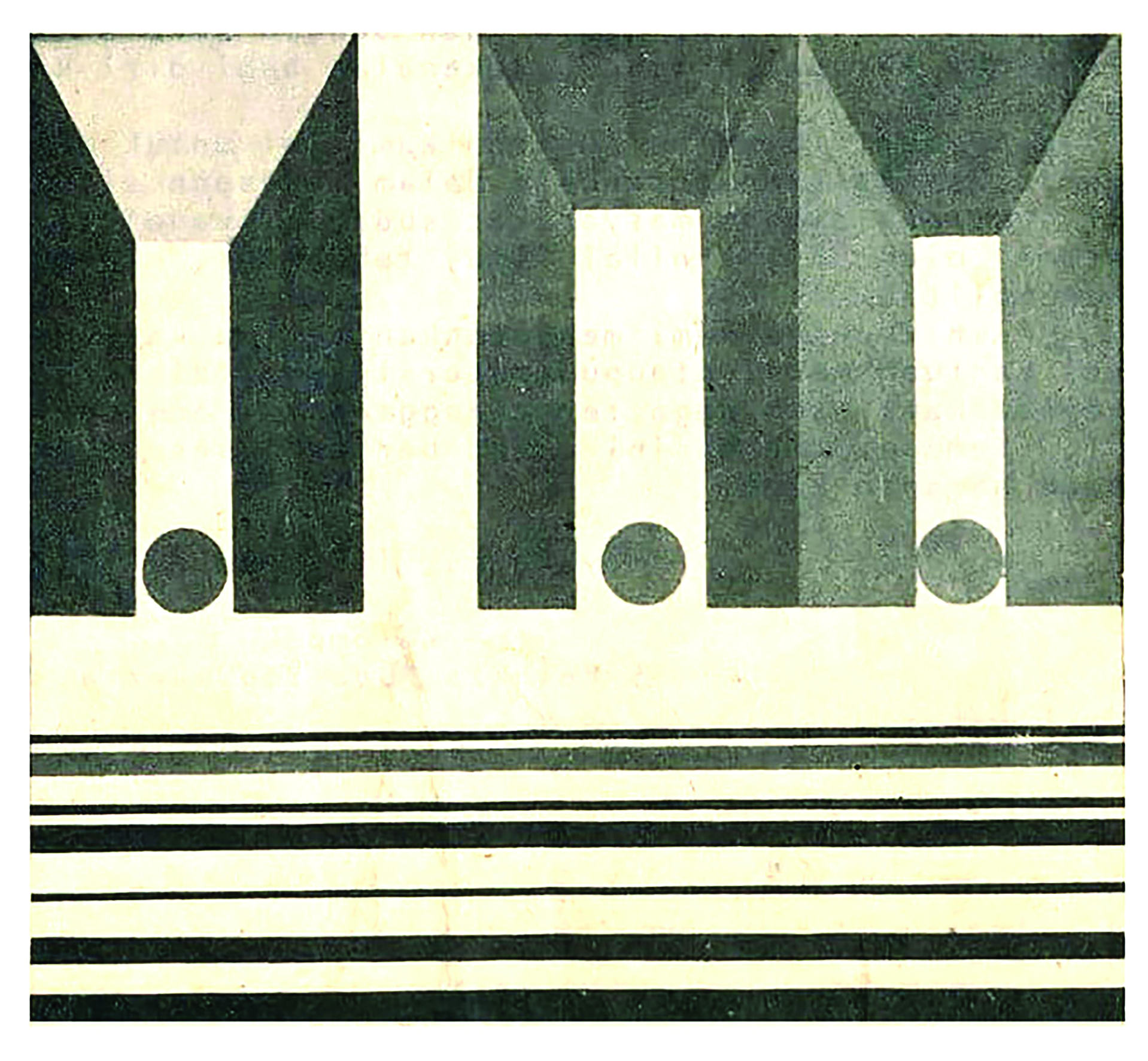

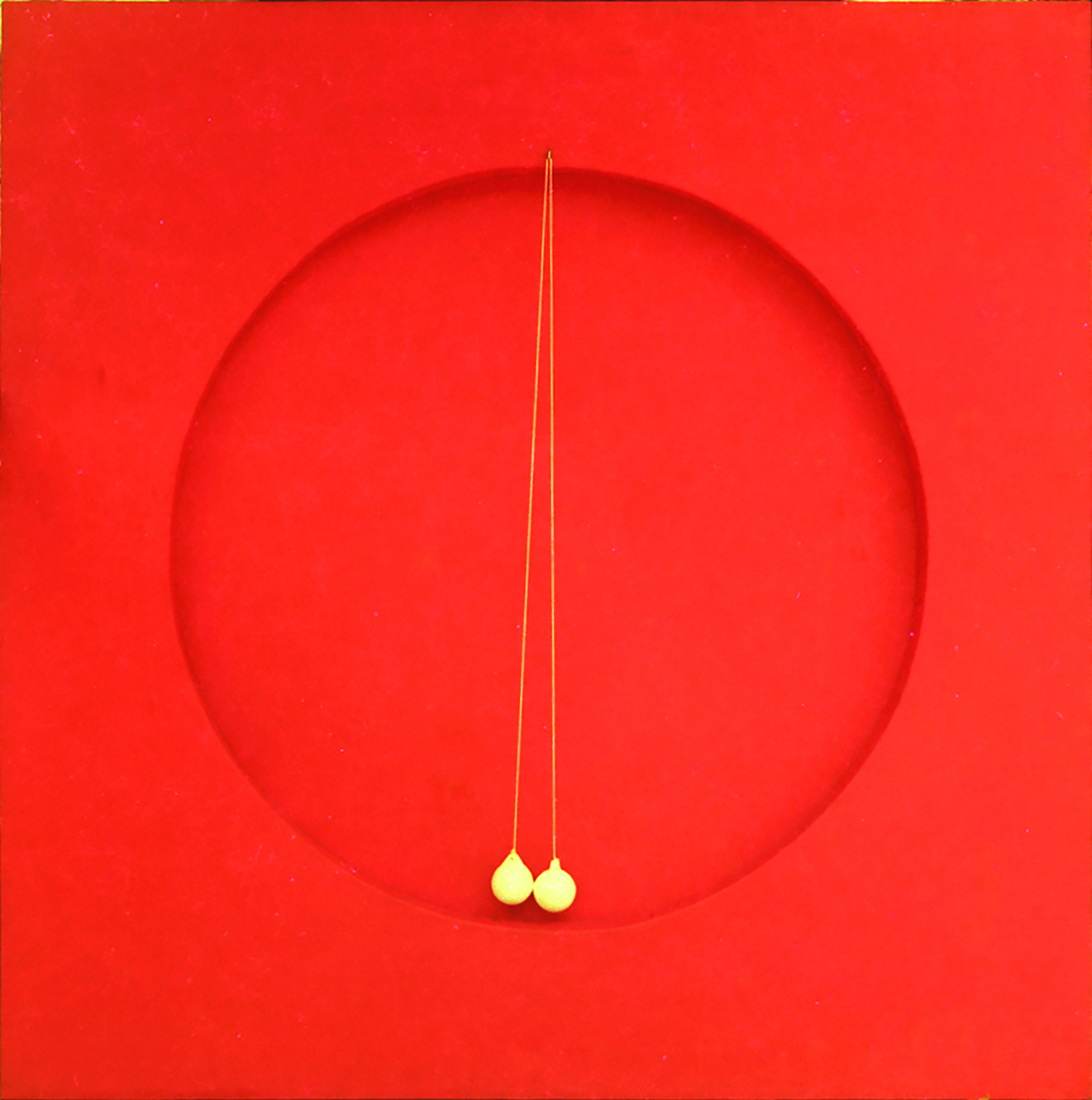

Time and Tides: Xiao Lu’s Recursive Art, 1989-2019

The inescapable focus of any commentary on the art of Chinese-born female artist Xiao Lu is the action of her firing a gun into her installation Dialogue 对话 (1988-89). That event took place on the opening day of the China/Avant-Garde Exhibition at the China National Art Gallery1 in Beijing on February 5, 1989, four months before the Tian’anmen Square Massacre. It is as if Xiao Lu herself was killed too on that fateful day when she was 26 years old. Her later artwork has received little critical attention, overtaken by a meta-narrative written in 1989 which, it must be said, she has been complicit in enabling through her silence. Fifteen years after the gunshot event, Xiao Lu challenged her own mute stance with an explosive revelation about the deeply personal circumstances relating to the creation of Dialogue and the shooting action. Her declaration called into question a powerful storyline that had developed around the work and its authorship which lessened, and in some instances removed, her agency from the shooting. Dominant male voices in the Chinese art world (emanating from art academies, art criticism and arts bureaucracies) had privileged grander claims of socio-politically inflected intent.

Since 2003—the year Xiao Lu spoke out—she has created a series of powerful artworks, many of them performance pieces. She is one of few Chinese artists who have persisted with the form. While she has moved forward in her artistic practice, she has continually been drawn back into the complex orbit of 1989, a watershed period in recent Chinese history that remains unsettled and contested to this day. Her ongoing reference to the events of 1989, driven by an obsessive desire to correct the historical record, arises from her determination to seek art world recognition for her work and her actions. Despite the notoriety that Xiao Lu has accrued as a result of the work, Dialogue and the related shooting action have also proved a difficult legacy for the artist and those associated with her to negotiate.

In her recent art Xiao Lu has confronted sensitive issues including the difficulties of communication between the sexes, gender inequality and individual justice within Chinese society. At the same time, she often returns to the gunshot—the moment that changed her life—an action that has been forever linked to the bloody suppression of pro-democracy protests in 1989, a highly sensitive topic which remains off-limits for investigation in mainland China. This essay re-positions Xiao Lu’s art as a significant strand of contemporary art practice that is intended to unsettle the viewer. It begins with a detailed account of Xiao Lu’s 2019 work Tides 弄潮, performed at daybreak on the beach at Stanwell Park outside Sydney at high tide2 on 18 January 2019. It is followed by contextualising sections designed to provide interpretive lenses through which to understand the work further. As with the majority of Xiao Lu’s performance works, Tides was developed in response to an invitation, in this case a commission to create a new work for the artist’s first retrospective exhibition, Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue 肖鲁:语嘿, at the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in Sydney.3 The essay argues that Xiao Lu’s art may best be understood as a recursive practice informed by cyclical time and the feedback loop of 1989 in which she and others closely involved in the gunshot event, remain caught.

Xiao Lu, Tides 弄潮, 2019, performance documentation, Stanwell Park, Sydney, 18 January 2019.

Commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney.

Photograph by Jacquie Manning. Courtesy the artist.

Action

Making her way to the shoreline of the beach at Stanwell Park as the sky begins to lighten, Xiao Lu gazes out at the Pacific Ocean. The photographers make their preparations. Cirrus and cumulus clouds catch the sun’s first rays; the ocean delivers slow, surging waves. It is a beautiful morning. Without giving any sign the performance is about to begin, Xiao Lu picks up a bamboo pole from the pile of 30, turns and makes her way down to the shore. Using one of the bamboo pole offcuts, she digs a hole in the sand and plants the first bamboo stake, making sure it stands upright. In the cool silence of the early morning, the only noise is the sound of the incoming tide. In the low light it is not possible to make out the artist’s features. She appears as a silhouette against the ocean’s waves, silvery and glistening at first light; a dark, rounded figure carrying a staff. The scene is monochrome, as if rendered in brush and ink.

As the sky becomes lighter a flock of seagulls comes shrieking and careening, flying close to Xiao Lu and around the bamboo poles. Xiao Lu continues to repeat the action undistracted. Before long the seagulls find greater interest on the upper beach. At times, in between planting the poles, Xiao Lu stops to gaze out to sea, catching her breath, her palms facing outwards in a gesture of apparent openness. Stillness follows activity. As she continues, the beachside town south of Sydney comes to life. Lights in distant houses turn on, signalling the start of the working day. Surfers arrive to ride the waves at high tide; morning walkers and runners work out, dog-walkers commune with nature before the mundane dictates of life take over the day. Passersby are bemused by the activity. Some stop and ask what is going on, curious that an art happening is taking place in their community; others merely take note of the strange occurrence and continue with their routines. The surrounding landscape gradually takes on colour. A cargo ship anchored out at sea is now visible on the horizon line. As morning dawns it is possible to see Xiao Lu’s features more clearly: her dark, crimped hair dyed with a shock of red and cut in a short bob, and her long red silk dress created for the occasion by her friend, female artist and designer Feng Ling.4 The intensity and brilliance of the reds contrast strongly with the earth-coloured sand, glistening white-blue ocean and the dark protective headland.5 Midway through the performance Xiao Lu realises the high tide will not be as high as had been anticipated during the previous afternoon’s reconnoitre, and she begins planting the poles much closer to the incoming waves. The distance back to the pile of poles is now greater and requires her to climb up two low banks of sand. The process is tiring and her face reddens. She stumbles and falls, her progress encumbered by the long silk designer dress, now heavy with the weight of water and sand. She injures her hand on the sharp diagonal edge of the bamboo offcut being used as a digging aid and continues by ‘winding’ the poles into the sand, securing their positions with her bare feet. Her toenails are painted bright red. As she winds the poles deep enough into the sand to stand upright, they oscillate in space creating invisible diagonal lines. All the while, Xiao Lu battles incoming waves which increase in intensity, destabilising her footing and that of the poles. Head down, body bent, using both hands and feet, it takes all of her energy to wield the poles into position. Focused on the task, her face is rarely revealed to the cameras. The long kimono-like sleeves of the dress billow in the wind while the wet dress clings to her legs, at times appearing translucent against the brightening ocean and sky.

Part way through the performance one of the bamboo poles moves and then begins a slow, elegant fall, passing from an upright position through a series of diagonals as it topples onto the sand. Rolling into the sea, it is later washed up on the beach and achieves a state of repose. Another pole succumbs to tidal force and is pulled out to sea. Xiao Lu continues with no apparent consideration of its plight. Played with by waves, then caught in a rip, it seems that the pole might well be taken out to sea, but it too is given up by the ocean and deposited back on the beach.

Xiao Lu, Tides 弄潮, 2019, performance documentation, Stanwell Park, Sydney, 18 January 2019.

Commissioned by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney.

Photograph by Jacquie Manning. Courtesy the artist.

After planting the last of 30 poles, Xiao Lu stumbles while climbing to the upper level of sand. Exhausted, she pulls herself up and turns to face the ocean, her arms outstretched. She signals that the performance has ended. It has lasted for one hour and ten minutes. The 28 bamboo poles that remain standing are silhouetted against the sand, sea and sky like lines inscribed on nature; their nobbly nodes ensuring that they are more than just straight lines. Out beyond the waves, male and female surfers who had entered the water soon after Xiao Lu began the performance are perched on their boards waiting for the next wave. The container ship on the horizon line is in a queue to come into dock.

Process 1

The conceptualisation of Tides involved a process of refinement and negotiation. An earlier proposal titled Ebbing Tide 退潮 involved a 30-day performance.6. Each morning the artist would collect debris from the strandline of a beach in Sydney—shells, stones, seaweed kelp and rubbish—and place it in a mound on the beach. Over time the daily accretions would form a small mountain. Wu Yanmei and Zhengze Yangping, two young artists who lived in the same artist compound as Xiao Lu in Beijing, would assist. Wu and Zhengze had documented Xiao Lu’s earlier performance work Coil (2018), filmed in her home-studio and would be in Sydney as artists-in-residence. The final proposal, Tides, retained the symbolism of the number thirty and the idea of durational performance, but over one day rather than thirty days. The proposal was communicated by email and then an image sent via WeChat.7 The sketch in brush and ink on paper adopted a horizontal format, unfolding from right to left like a Chinese handscroll. It began with the title 弄潮 or Tides, written in a vertical line, echoing brush strokes that gave form to a sparse grove of poles. A series of gently curving horizontal lines suggested a shoreline; short dashes animated a roiling sea and waves with white caps. Wandering through the scene was a figure facing the ocean, head down, walking in a long gown pulled taut by the weight of water and sand. There was nothing to indicate that the figure was necessarily a woman; it could be an ancient sage, a hag, a shaman even. The sketch had a timeless quality. The brushstrokes varied in intensity, some heavy with wet ink, others dry and ethereal as the ink on the brush depleted in the process of painting. The rhythm of wet and dry consistencies appeared to echo the artist’s breath, suggesting the repeated action of returning the brush to the inkstone to replenish it with ink. Painted in Beijing in September 2018, the sketch had an autumnal chill suggesting the difficulty of imagining the scene on a beach in Sydney in high summer. Despite her art school training in oil painting and drawing inspired by French academic and Soviet models, Xiao Lu has come to prefer the subjectivity of calligraphy-and-ink painting, drawing on the remembered practices of reading and writing and the visualisation of the image in the mind’s eye. She has developed a regular practice of calligraphy and routinely uses ink sketches to give form to her performance concepts. Ink and calligraphy feature prominently in Xiao Lu’s works.8

As with all of Xiao Lu’s performances, the work would not be fully known until the performance was completed. While the brush-and-ink painting conveyed her mental image of the work and was used by the organisers to support the realisation of the performance, at each point in the process of discussion and preparation Xiao Lu insisted on being free to change the work at any time. Used to channelling energy from her surroundings, she insists on keeping open the possibilities inherent in chance occurrences.

Xiao Lu, Tides 弄潮, 2018, performance concept, brush and ink on paper. Courtesy the artist.

Context I – 30 years

The 2019 exhibition Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in Sydney marked the 30th anniversary of Xiao Lu’s arrival in Australia. It was her first retrospective exhibition.9 It coincided with the 30th anniversary of what proved to be the turning point for Xiao Lu—the China/Avant-Garde Exhibition, a large and sprawling survey of experimental art in Beijing in 1989.10 Xiao Lu was one of the youngest exhibitors then and one of only a few women artists whose work was selected. On the opening day of the exhibition on 5 February 1989, the eve of the Lunar New Year, Xiao Lu famously fired a gun into her installation Dialogue 对话 (1988-89). She had completed the work the previous year as part of her graduation portfolio for the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou. The provocative act of submitting an installation for her graduation from the oil-painting department was indicative of the defiant spirit of the times.11 She was the only woman in a class of 11 students. A readymade, Dialogue comprised the facades of two telephone booths, separated by mirror glass and a plinth on which was placed a red phone, the receiver dangling off the hook. Photographic portraits of a woman and a man, viewed from behind and seemingly talking into the phone, were affixed to the interior of the booths, the mise-en scène suggesting the impossibility of dialogue.

After the shooting, Xiao Lu and Tang Song attempted to flee the scene. Xiao Lu slipped into the crowd and left the gallery. She later turned herself in to the police. Tang Song, a male student in the brush-and-ink painting department at the Hangzhou art academy, whose work was not included in the exhibition, and a friend of Xiao Lu’s, was arrested and taken into custody.12 After their release a public statement was prepared denying that the ‘shooting incident’ was politically motivated, which was what the authorities most feared. The statement, signed by both Xiao Lu and Tang Song, formally linked Tang Song to the shooting event, and by association to Xiao Lu’s installation Dialogue, which in the process had been transformed into a stage for what was understood to be an avant-garde art happening.13

1989年.jpg)

Xiao Lu, Dialogue 对话,1989, documentation of installation and shooting, China/Avant-Garde exhibition, National Art Gallery,

Beijing, 5 February 1989. Reproduced courtesy of Wen Pulin Archive of Chinese Avant-Garde Art and Xiao Lu.

Four months later, the People’s Liberation Army brutally suppressed the student-led protests in Tian’anmen Square, Beijing, in a tragedy widely known as ‘June 4’ or the ‘Tian’anmen Square Massacre.’ A nationwide crackdown on dissent followed precipitating the departure of many people from China, including Xiao Lu whose gunshots would later be described as a prelude to the massacre. They “transformed the entire China/Avant-garde Exhibition into one big, chance happening that underscored the opposition to the official line and the political sensitivity of the Chinese avant-garde…” wrote Li Xianting, one of the curators, for example.14 The unimagined brutality of the crackdown on dissent and strictures placed on experimental art further overlaid the work with activist intention, associating it with a defeated idealism. In Li’s words: “The fate of the exhibition was a precursor to the fate of the student movement at Tian’anmen, in the sense that the China/Avant-Garde show became the final demonstration of 80s avant-garde art, marking the conclusion of an era and also the end of its ideals.15

Xiao Lu left China in December 1989 and found refuge in Australia. She would live in Sydney for seven years. She was eventually joined by Tang Song.16 They would return to China together in late 1997. Gao Minglu, the principal curator of the China/Avant-Garde Exhibition, later observed that with Xiao Lu and Tang Song’s removal of themselves from the Chinese art world, a situation resulted in which ‘[n]ormal art historical research [into the shooting event at the China Art Gallery] became completely impossible.17

Context II – Asserting agency

In 2003 Xiao Lu and Tang Song separated acrimoniously, prompting Xiao Lu to finally break her long silence about Dialogue and the ‘shooting incident.’ At the age of 41 she found herself unmarried, childless and in the difficult situation of being on her own. In a series of emails, online posts and performance artworks she claimed that the act of shooting the gun was an integral element of Dialogue.18 Her determination to present her version of events led to a semi-fictional autobiography titled Dialogue 对话 published in 2010 in Chinese and English by Hong Kong University Press.19 In a foreword, Gao Minglu, who had since relocated to the US, describes Xiao Lu’s shooting action as “no dogmatic sociology or random act of conceptualist significance, but, on the contrary, a long-term build-up of oppressions dating back to Xiao Lu’s youth.” Xiao Lu’s story, he wrote, is “a female tragedy within the specific system of Chinese socialism.20

Xiao Lu insisted that the installation and the shooting arose from a complex personal crisis, following a much earlier episode of sexual abuse that occurred while she was a minor studying at high school in Beijing and involving a senior male artist who was trusted as a guardian figure. Xiao Lu described the complex and multi-layered trauma as representing “the death of my body” and “my illness.”21 In aiming the gun at her image reflected in the artwork, Xiao Lu had staged a virtual suicide. The bitter separation from Tang Song 15 years later amounted to a double wound and prompted her decision to finally speak out. The motivation for Xiao Lu’s symbolic act of self-annihilation came from a deep, dark, personal space. Her revelation of it was as shocking as it was brave.

For those in the Chinese art world who linked the shooting to Tang Song and attached larger artistic and socio-political meanings to the event, Xiao Lu’s belated explanation proved difficult to accept. Her attempt to correct the historical record provoked disbelief and anger. It amounted to an undoing of the heroic narrative of the avant-garde and caused humiliation and loss of face for many people, herself included.22

Xu Hong, a leading Beijing-based female art critic, supported Xiao Lu’s claim of agency, citing qualitative differences in Xiao Lu’s and Tang Song’s approaches to art-making among other factors. While Xu Hong criticised Xiao Lu’s earlier silence as “a kind of acquiescence,” she took aim at the persistent “dictatorship of ideology” operating in Chinese art criticism at the time that devalued the expression of emotion in art. In her 2006 essay on Xiao Lu and Dialogue, Xu Hong drew attention to the denigration of women’s creative practice in art world discourse in China (mostly written by men), “perpetuating the myth of male greatness and female insignificanc.”23 In the end, Xiao Lu won the moral battle over authorship through market recognition.24 In 2006 a still photograph of Xiao Lu shooting her installation and a facsimile that she had made of Dialogue (the original work was lost or destroyed in the tumult after June 4, 1989) were listed under Xiao Lu’s name and sold at auction by China Guardian. The installation, which sold for 2,310,000 yuan, was acquired for the Taikang Art Collection, owned by Chen Dongsheng’s Taikang Life Insurance Co. Ltd. and managed by female curator Tang Xin.25 Ten years later, Dialogue was borrowed for the SHE: International Women Artists Exhibition (2016) curated by Wang Wei, the powerful female director of the Long Museum, a private art museum she established in 2014 with her husband Liu Yiqian in Shanghai. In a significant breakthrough, the exhibition juxtaposed the work of Chinese and international artists. Dialogue was placed in the final section of the exhibition titled Self-expression, which also included the work of international artists Jenny Saville, Tracey Emin, Bridget Riley, Miriam Cahn, Shirin Neshat, Ulay and Marina Abramovic, and Ana Mendieta.26 In the catalogue entry for Dialogue, the significance of Xiao Lu shooting a gun into her installation is summed up as having pushed performance art into extreme dialogue with legal and social systems and at the same time raised debate about the discourse of power between the sexes. The exhibition at Long Museum (West Bund) positioned Dialogue as an influential work in the development of women’s art.27

Context III – Becoming a performance artist

Since 2003 Xiao Lu has fired a gun at her own image (15 Gunshots… From 1989 to 2003); staged a mock funeral/wedding in which she marries herself (Wedlock, 2009); asked members of the public ‘what is love?’ (What is Love?, 2009); invited strangers to drink red wine with her, becoming so intoxicated she was rushed to hospital (Drunk, 2009); had her head shaved (Bald Girls, 2012); sought sperm donors in an exhibition in Yan’an that commemorated Mao Zedong’s 1942 “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art” (Sperm, 2006); ran naked from the Museo Diocesano di Venezia exposing her mature body and jumped into the Grand Canal (Purge, 2013); doused herself with a bucket of ink and then water (One, 2015); accidentally severed a tendon while using a sharp knife to cut her way out from within a tower of ice, when she was rushed to hospital and underwent emergency surgery (Polar, 2016); rolled around drunk and wailing in Piazza San Marco in Venice after consuming cup after cup of white spirits (baijiu), (Holy Water, 2017), and once again ended up in hospital.28

These works have been motivated by an unwillingness to accept the status quo and a determination to ask questions as well as to seek recognition as an artist in her own right. No longer content to hide, Xiao Lu has unflinchingly confronted details of her messy and at times traumatic private life. In the process she has challenged stereotypical attitudes towards women and drawn attention to issues of gender inequality and injustice in the Chinese art world and society more generally. Placing herself in awkward situations and making audience members part of the structure of the dynamics of viewing and experiencing, she works with intuition and feeling, living on her nerves. Her art is informed by a raw, disruptive aesthetic that draws on deep emotion, extreme action and chance.

The work Tides (2019) reflects on Xiao Lu’s life over the past thirty years, including the seven years that she spent in Australia—a complex and little remarked upon period of displacement and life experience that is nonetheless central to understanding her artistic formation. It links the histories of Australia and China; connections that have been forged over time by people from both countries crossing the Pacific Ocean for trade and enquiry, opportunity and refuge. Oceans connect land masses and islands. Shorelines are liminal spaces, ever-changing, with no strict boundaries or edges. The constant ebb and flow of water, fluid and yielding, wears away rock; what is soft is strong.29 The fluctuation of tides, the ocean’s breath, reminds us that our being and our actions are influenced by forces that are beyond our immediate control.

Tides joins a series of powerful works that reference the 1989 China/Avant-Garde Exhibition, notably 15 Gunshots… From 1989 to 2003 (2003), Dialogue About Dialogue (2004), and Wedlock (2009).30 What occurred in 1989 was larger than any one individual could anticipate or control. The achievement and significance of Dialogue (1988-89) is its ongoing resonance as a work of art generated by complex sets of conditions and circumstances that have in turn created multiple readings and interpretations. It has generated powerful new works that arise from its instability.

Process II

Originally for Tides Xiao Lu proposed to use poles harvested from a thicket of trees close to her home in Beijing, but the Australian government’s customs and quarantine regulations made that difficult to realise. Bamboo was therefore a material of compromise. It is native in China and there are three species that are native to northern Australia.31 It is evergreen and flourishes in winter making it an emblem of longevity in Chinese culture. Historically, bamboo is a subject favoured by Chinese brush-and-ink artists who see in its uprightness and tenacity the human qualities of integrity and plainness combined with elegance. Along with the plum blossom, orchid and chrysanthemum, bamboo is known as one of the ‘Four Gentlemen,’ representing the four seasons and four aspects of ideal male character. It is a material freighted with cultural meanings and gendered significance.

The Chinese title of Tides, Nongchao 弄潮—literally ‘riding the tide’—contains allusive meanings that run deep in the culture of modern China.32 The character chao 潮 which can mean ocean tide, (social) current or trend, appears in the compound words sichao 思潮 meaning trend of thought, xinchao 新潮 meaning new wave, and gaochao 高潮 meaning high tide, upsurge or climax.

Having acquired 30 bamboo poles and carried out the necessary logistical preparations, the 4A support team travelled with Xiao Lu to the beach at high tide to discuss the performance, filming and photography that would take place the following morning.33 Xiao Lu walked up and down the beach, which was strewn with bluebottles (Physalia physalis), those brilliant blue marine hermaphrodites that periodically wash up on Australian beaches in summer, carried onshore by winds and warm ocean currents, and sting. A location for the performance was decided upon and safety procedures worked out, including the possibility of bluebottles. The pile of 30 three-metre long bamboo poles would be placed in position before daylight. Xiao Lu would plant them one by one along the shoreline, her passage to and fro creating a series of lines radiating outwards from the pile. The end of each bamboo pole was pre-cut on a diagonal to create a pointy end and the interior diaphragms of the nodes in the lower section removed to make it easier to drive the poles into the sand. Xiao Lu practised planting a couple of poles. The bamboo offcuts proved useful for digging holes in the sand. The two videographers, David Ma and Zhengze Yangping, and two still photographers, Jacquie Manning and Wu Yanmei, discussed their respective positions and approaches. An arc would be drawn in the sand to indicate the photographic no-go zone. Xiao Lu did not brief the photographers, preferring that they find their own way to record the performance. Only Xiao Lu, Jacquie Manning and David Ma would enter the water. The photographers would wear thick socks to minimise the impact of any stings from bluebottles. Zhengze Yangping and Wu Yanmei, who could not swim, were asked to stay well away from the shoreline. If Xiao Lu got into trouble—she also cannot swim—there were procedures in place to go to her aid.34 Xiao Lu insisted that no matter what happened, the cameras must keep rolling. The performance would end when she gave the signal.

Setting out from the hotel at around five in the morning on 18 January 2019, the crew set up a base for equipment and supplies immediately behind the performance site, protected by a sand dune. The bamboo poles, tied into bundles of ten, were carried from the van and placed in position. It was pitch black. Torches and mobile phones provided light. The topography of the beach appeared to have altered significantly overnight. It was more undulating, with two steep rises appearing from the shoreline to the beach like steps. The reconfigured topography would make for a more strenuous performance and potentially create a more dynamic visual effect as the incoming waves forced their way up and onto the beach.

Xiao Lu, Tides 弄潮, 2019, performance documentation, Stanwell Park, Sydney, 18 January 2019. Commissioned by 4A Centre

for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney. Photograph by Jacquie Manning. Courtesy the artist.

In conceptualising the performance it was impossible to know if any of the 30 bamboo poles would remain standing, and if so, for how long. During the course of the performance one pole succumbed to the onslaught of the sea, toppling over—its fate determined by the churn of waves. Another pole was swept out to sea and finally washed up on the beach to form part of the strandline. Separated from the ragged line of poles by some 50 metres and abandoned by cameras that were trained on the artist, it served as a reminder of the role played by chance in Xiao Lu’s art, and of the unexpected events that are part of the heave and pitch of life.

Coda

In 2021 Xiao Lu returned to Sydney where she currently lives and works. Tang Song passed away in Shanghai in 2022. The same year she discovered she had a serious heart condition and underwent an operation to install a defibrillator to prevent a sudden heart attack. Her doctor has advised against the kind of strenuous physical and emotional activity that past performance works such as Tides have demanded.

Footnotes

1 Known today as the National Art Museum of China. See China/Avant-Garde Exhibition, Asia Art Archive.

2 On Friday 18 January 2019 high tide at Stanwell Park was 1.56 metres at 6.29am. First light was at 6.07am and sunrise at 6.33am.

3 Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, 19 January–24 March 2019, formed part of the author’s Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellowship research project ‘Reconfiguring the World: China. Art. Agency. 1900s to Now’ (FT140100743). The exhibition was co-curated by Claire Roberts, Mikala Tai and Xu Hong. The exhibition and associated public programs were supported by the ARC, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne, and the Australia-China Council.

4 Feng Ling is a graduate of the Harbin Institute of Art (BA, oil painting) and the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing (MA, oil painting). In 2003 she established the Feng Ling Art and Design Studio in 798 Art District, Beijing. Xiao Lu and Feng Ling were among the artists included in the exhibition Sworn Sisters, Vermilion Art, Sydney (2018).

5 In Chinese culture red is associated with the age-old desire for happiness and good fortune.

6 Xiao Lu, Performance art proposal, Ebbing Tide (provisional), 19 July 2018.

7 Xiao Lu, email to the author, 8 August 2018. The initial proposal refers to 30 blue-coloured poles.

8 See for example, Quiet Contemplation (1986), Dialogue (1988), Love Letters (2009-10), Menopause (2011), Skin Paper Room (2013), One (2015), People (2016), Yin Yang Calendar (2013-14), Suspended (2017). See also: Guest 133-151; and Gladston and Howarth-Gladston, 120-129.

9 For details of the exhibition and associated public programs see “Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue,” 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. For an analysis of a day-long workshop held at the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in conjunction with the exhibition; see also Alex Burchmore, “The China/ Avant-Garde Exhibition and Xiao Lu: 30 Years On.”

10 The exhibition had been developed over a number of years by a large group of curators, art critics and art editors including Gao Minglu, Fan Di’an, Fei Dawei, Hou Hanru, Kong Chang’an and Li Xianting. Earlier attempts to stage the exhibition had been thwarted by the government’s Anti-Bourgeois Liberalisation campaign of 1987.

11 In order to satisfy departmental criteria Xiao Lu finally submitted Dialogue plus Red Wall (1988), a competent realist oil painting depicting two Tibetan women standing against a weathered red wall. The subject derived from an academy painting trip to Tibet and was typical of work submitted for assessment at that time.

12 In video footage of the shooting filmed by Wen Pulin and released much later, after Xiao Lu had fired the first shot, Tang Song can be heard shouting “what about another shot.” See “Interview: Xiao Lu” by Carol Yinghua Lu, 14 March 2006 for Asia Art Archive (AAA). This interview records in detail Xiao Lu’s recollection of the creation of Dialogue, the shooting incident and her relationship with Tang Song. See also copies of the Arbitration Notices issued to Xiao Lu and Tang Song, detaining them for five days (Xiao Lu was released after three) for unlawfully carrying a firearm, dated 6 February 1989, in Li Xianting Archive/ AAA. With thanks to Genevieve Trail for assisting with access to these and other related materials.

13 Tang Song’s understanding of his involvement in the ‘shooting incident’ was conveyed in a letter to Hans van Dijk, dated 10 March 1989, Hans van Dijk/ AAA. See also Borysevicz, “Tang Song (1960-2022)” in Artforum, 15 July 2022; and Weng Zijian, “Tang Song fang tan (Interview with Tang Song)” recorded at Tang Song Studio, Hangzhou, on 27 November 2009.

14 Li Xianting xix. See also Gao Minglu viii.

15 Li Xianting xix.

16 In May 1991, after living in a resettlement camp in Hong Kong for six months and without any prospect of soon obtaining a visa for Australia, Tang Song stowed away on a cargo ship bound for Australia. On arrival in Sydney, Tang was arrested as an illegal immigrant and spent seven months at Villawood Detention Centre. In his artistic biography, he describes the journey as “a unique example of performance art.” See Tang Song, Curriculum Vitae, Xiao Lu in a fax communication with the author, June 28, 2002.

17 Gao Minglu viii.

18 After a chance encounter and conversation with Gao Minglu in Beijing, Xiao Lu formally wrote to Gao who, since 1991, had been living and working as an academic in America. She also wrote to Li Xianting. The details of their exchanges were later published online and included in a dossier of material relating to Dialogue that formed part of the performance Dialogue about Dialogue (2004). In that work Xiao Lu stood in front of a replica of the Dialogue installation, read out a poem explaining her actions in 1989, and then proceeded to a cut a lock of her hair, which had not been cut since 1989, placed it on a dossier of documentary materials and handed it out to audience members, one after another. The lock of hair was intended as a sign of sincerity and truth. See references to the communication with Gao in Xiao Lu, Dialogue, 205. See also Carol Lu’s “Interview: Xiao Lu.”

19 The English language edition was translated by Archibald McKenzie.

20 Foreword, Dialogue xiii.

21 Dialogue 1-2.

22 See Gao Minglu xiii.

23 Xu Hong, “Ta, Tamen, Ta, (Her, Them, He)” 16. The essay was written in response to discussion at the Second Shenzhen Critics’ Forum, 30 November 2005. Xu Hong was the only female among 29 critics from across China. See also Xu Hong, “Zouchu shen yuan (Walking Out of the Abyss)” 17. Xu Hong was a participating artist in the 1989 China/Avant-Garde Exhibition.

24 For many years Tang Song continued to list the ‘shooting incident’ in his Curriculum Vitae. Tang Song’s work Crime Scene (Fanzui changjing, 2013) included in his online solo exhibition on Artshare.com alludes to his ongoing pre-occupation with the incident. See “Kuangre jiqing de siyu (Whispers of Raging Passion),” Artshare.com.

25 China Guardian Auctions Co., Twenty Years of Contemporary Chinese Art (Zhongguo dangdai yishu ershinian, Zhongguo Jiade 2006 qiuji paimai hui), 22 November 2006, items 260 and 261.

26 The accompanying publication, by Wang Wei (ed), is divided into four chronological chapters. The first chapter Self-annihilation was reserved for historical works by Chinese artists; the second Self-liberation included the work of one international artist, France Leplat; the following chapter Self-introspection included works by Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin, Yoko Ono, Kiki Smith, Mona Hartoum, Louise Bourgeois, Marlene Dumas, and Joan Mitchell.

27 Wang Wei 224, 246.

28 For details of works see Xiao Lu’s website Xiao Lu Art.

29 This idea alludes to the words of the ancient writer and founder of philosophical Daoism, Laozi, in the Dao De Jing, chapters 43 and 78. See Dao De Jing, Chinese Text Project.

30 The works were commissioned to mark the 30th, 15th and 20th anniversaries of the China/Avant-Garde Exhibition respectively.

31 For an analysis of the biogeographic implications of Australian native bamboo, see Franklin, Taxonomic interpretations of Australian native bamboos.

32 See Geremie R. Barmé, “Tides Chao 潮.” With thanks to Geremie for drawing this essay to my attention.

33 The support team comprised Mikala Tai, Michael Do, Kai Wasikowski from 4A, and

Claire Roberts.

34 Mikala Tai, Director of 4A, distributed a document outlining procedures and safety instructions for all those present at the performance.

References

Barmé, Geremie R. “Tides Chao 潮.” China Heritage Quarterly, no.29, March 2012, http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/glossary.php?searchterm=029_chao.inc&issue=029. Accessed 28 February 2023.

Borysevicz, Mathieu. “Tang Song (1960-2022).” Artforum, 15 July 2022, https://www.artforum.com/passages/tang-song-1960-2022-88813. Accessed 28 February 2023.

Burchmore, Alex. “The China/ Avant-Garde Exhibition and Xiao Lu: 30 Years On.” 4A Papers, Issue 6, 2019, https://4a.com.au/articles/china-avant-garde-exhibition-xiao-lu-alex-burchmore. Accessed 28 February 2023.

“China/Avant-Garde Exhibition.” Asia Art Archive. https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/fei-dawei-archive-exhibition-documents/object/chinaavant-garde-exhibition-exhibition-information-english. Accessed 17 April 2023.

China Guardian Auctions Co., Twenty Years of Contemporary Chinese Art (Zhongguo dangdai yishu ershinian, Zhongguo Jiade 2006 qiuji paimai hui), 22 November 2006, items 260 and 261, https://auction.artron.net/paimai-art43820260. Accessed 28 February 2023.

Dao De Jing. Chinese Text Project, https://ctext.org/dao-de-jing. Accessed 28 February 2023.

Franklin, Donald C., Taxonomic interpretations of Australian native bamboos (Poaceae: Bambuseae) and their biogeographic implications, Telopea 12, no. 2, November, 2008, pp. 179-191. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228762508_Taxonomic_interpretations_of_Australian_native_bamboos_Poaceae_Bambuseae_and_their_biogeographic_implications. Accessed 23 February 2023.

Gao, Minglu et al. “Foreword.” Dialogue. Translated by Archibald McKenzie, Hong Kong University Press, 2010, pp. vii–xvi. Online: JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1xwc5m.3. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

Gladston, P. and L. Howarth-Gladston. “Beyond Dialogue: Interpreting Recent Performances by Xiao Lu.” di’van: a Journal of Accounts, Vol. 5, 2019, pp. 120-129.

Guest, Luise. “Reclaiming Silenced Voices: Feminist Interventions in the Ink Tradition.” Shifting the Ground: Rethinking Chinese Art, special issue of Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, Vol. 21, no. 1, 2021, pp. 133-151.

“Kuangre jiqing de siyu (Whispers of Raging Passion): Tang Song Solo Exhibition.” Artshare.com, http://www.artspy.cn/activity/view/5342. Accessed 28 February 2023.

Lu, Carol Yinghua. “Interview: Xiao Lu.” Asia Art Archive, 14 March 2006, https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/library/interview-xiao-lu

Li Xianting. “Major Trends in the Development of Contemporary Chinese Art.” China’s New Art, Post-1989. Hanart T Z Gallery, 1993, pp. x- xxii.

Li Xianting. “1989 China/Avant-Garde Exhibition.” Li Xianting Archive/ Asia Art Archive. https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/li-xianting-archive-1989-chinaavant-garde-exhibition-beijing. Accessed 17 April 2023.

Roberts, Claire, Mark K. Erdmann & Genevieve Trail. Shifting the Ground: Rethinking Chinese Art, special issue of Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, Vol 21 no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-4.

Van Dijk, Hans. “Letter from Tang Song to Hans van Dijk.” 10 March 1989, Hans van Dijk Archive/ Asia Art Archive, https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/hans-van-dijk-archive-tang-song. Accessed 17 April 2023.

Wang Wei, editor. Tamen: Guoji nüxing yishu tezhan (SHE: International Women Artists Exhibition). Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 2016, pp. 224, 246.

Weng Zijian. “Tang Song fang tan (Interview with Tang Song).” Materials of the Future: Documenting Contemporary Chinese Art from 1980-1990/ Asia Art

Archive, https://www.china1980s.org/tc/interview_detail.aspx?interview_id=92. Accessed 28 February 2023.